13 January 2015

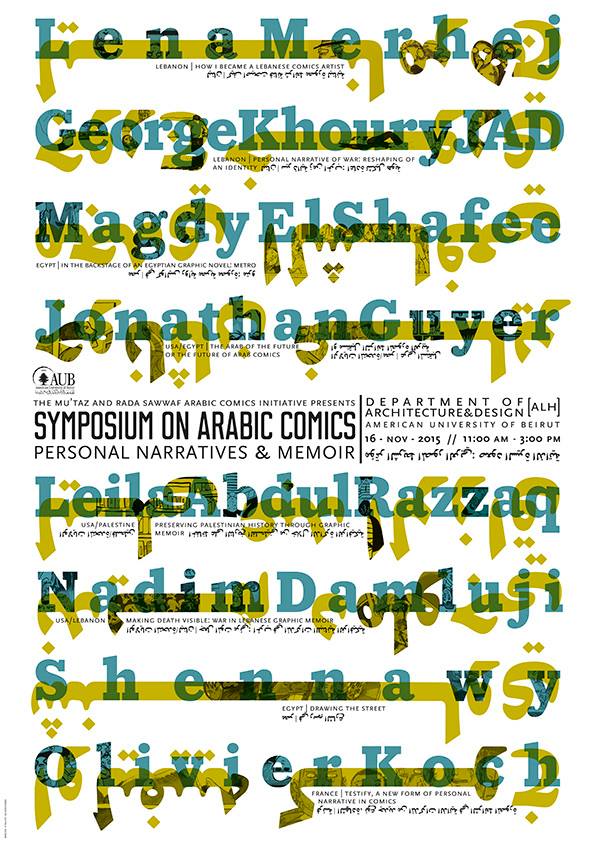

I had flown to Beirut for the first annual Symposium on Arabic Comics to deliver a paper about the Franco-Syrian comic artist Riad Sattouf’s incredibly popular graphic novel, The Arab of the Future. As part of the American University of Beirut’s symposium, and kicking off the events, a top Lebanese wedding planner had designed a 400-person gala in celebration of the deceased Lebanese cartoonist Mahmoud Kahil. AUB would bestow seven awards to leading Arab cartoonists.

Soon after arriving, I had sent out a group e-mail message to friends to coordinate a get-together, while preparing my remarks for Monday’s conference in the hotel. One journalist immediately replied, “Welcome! Two guys just blew themselves up in the Dahieh!” I turned on the news and watched reports of twin suicide bombings that had ripped through Beirut’s Dahieh neighborhood, which killed 43 and injured at least 200. Lebanon had endured 15 years of civil war, several Israeli invasions and plenty of car bombs. By the summer of 2011, the violence of the Syrian civil war had entered Lebanon, but this was the largest attack in the capital in over two years.

It was suddenly strange to be in Beirut for a comic confab. Lina Ghaibeh, director of the American University of Beirut’s Arabic Comics Initiative, postponed the comic gala indefinitely, “in recognition of the senseless tragedy that took place yesterday in Beirut, in sympathy with the many lives lost.” Ball gowns and glitzy centerpieces were not appropriate for this moment of mourning and self-reflection, with so much death so near.

Instead she gathered the dozen out-of-towners on the third-floor terrace of the chic restaurant Abdel Wahab. The award winners were disappointed to have missed the big night, having flown to Beirut for just a round of mezze. But it was heartening to sit together at a long table, getting to know the region’s top comic chroniclers and chewing the fat about art, in spite of terror.

“Sorry for the sad events,” said Ghaibeh, raising a glass, welcoming Egyptian, Jordanian, Palestinian and Syrian artists, and informally announcing the award winners (though the results have still not been made public). As hot meat pastries and pungent baba ghanouj topped with pomegranate seeds were passed around, the crowd loosened up. My journalistic instincts perked up, as I jotted down little details in a notebook under the table, but I soon realized that I might be making some of the guests uncomfortable, and that I was removing myself from the present experience.

Among esteemed cartoonists, I wanted to ask each one about his or her reactions to the Beirut bombings. But having attended many such dinners this fall, I learned that, rather than posing a contrived query about an event’s meaning or political implications, it’s better to let the conversation flow. In fact, the Beirut bombings didn’t enter the discussion. Instead, Amjad Rasmi, cartoonist for the popular pan-Arab daily Asharq Al-Awsat, asked me how repression in Egypt is affecting the country’s press, as he incessantly lit cigarettes. The elusive Jordanian comic artist known as Flyin’ Dutchman, running a hand through his floppy hair, described how his narratives are incredibly personal, unwittingly verging on the existential. The Lebanese artist and animator George “Jad” Khoury handed me plate after plate of kibbeh nayeh and salads, and then expressed his admiration for foreign correspondents who put their lives on the line to cover the news.

By the time platters of fruit and rose-water flavored sweets were brought out, everyone was glued to his or her phone. Another tragedy was underway, an attack in Paris. The scope of the event was not yet clear: one person said that President Hollande had been evacuated from a soccer match; another mentioned a shooting at a concert hall. Those with family and friends in Paris were making frantic phone calls. We were torn between celebrating the accomplishments of our peers and trying to make sense of another act of terror, while the first was still raw.

Earlier this year, European and American institutions cancelled events with cartoonists out of fear of an attack following the Charlie Hebdo killings in Paris. Four days after Beirut’s suicide bombings, the Symposium on Arabic Comics, an academic gathering pegged to the aborted gala, convened as planned. So too did other gallery openings and shows throughout Beirut. The exhibitions and performances put into relief questions about the durability of hope and the ambiguity of Arab identity during a moment of unmitigated violence. Like the dinner with comic artists, these artistic expressions alternated between states of passion and apathy, in which participants were at once sensitized and desensitized to extreme violence. If this tension is simply part of the experience of living in the Arab region, then art—at its best—can offer another perspective. Artists, in reflecting on current and past events, can provide the opportunity to contemplate issues that are otherwise incomprehensible. I saw this at the conference, in other art events, and in the wider response of Arab cartoonists to the tragedies in Beirut and Paris.

Arabs of the Future

The comic symposium’s day of academic presentations was themed around personal narratives and memoir. Of the eight presenters, one French scholar had flown back to Paris as his sister had been injured in the ISIS rampage. The rest remained in Beirut, eager to join the cutting-edge initiative’s inaugural conference. Nadim Damluji, a young Lebanese-American researcher, began his lecture by thanking convener Lina Ghaibeh for carrying on with the symposium despite, “this tremendous, senseless violence that happened in Beirut.”

“I know it’s hard for me,” said Damluji, as he stepped toward the podium. “I woke up this morning thinking I’m going to talk about comics, it seems so irrelevant in spite of all of this but in fact, ironically, what I’m going to be talking about is how art helps us make sense of senseless acts.”

Damluji went on to present a range of war narratives, framing his talk around The Diary of Anne Frank and Picasso’s Guernica, before delving into the emerging canon of Lebanese comics about war. He argued that comics make “the invisible visible in the interplay of panels.” These hidden stories are not always of blood and guts. War can be boring, as he showed in a series of Lebanese comic strips. Zeinab Abirashad’s childhood memoirs of the civil war depict weeks spent waiting around, killing time in a safe room over chess or decks of cards, while the city is under siege. Similarly, Mazen Kerbaj’s stream of consciousness sketches of enduring Israel’s 2006 assault on Beirut capture the banality of war, from what’s on grocery store shelves amid air raids to how the author never left home without a toothbrush in case he was trapped elsewhere. These mundane details don’t detract from the death of innocents, but rather complete the picture for readers unfamiliar with the true experience of conflict.

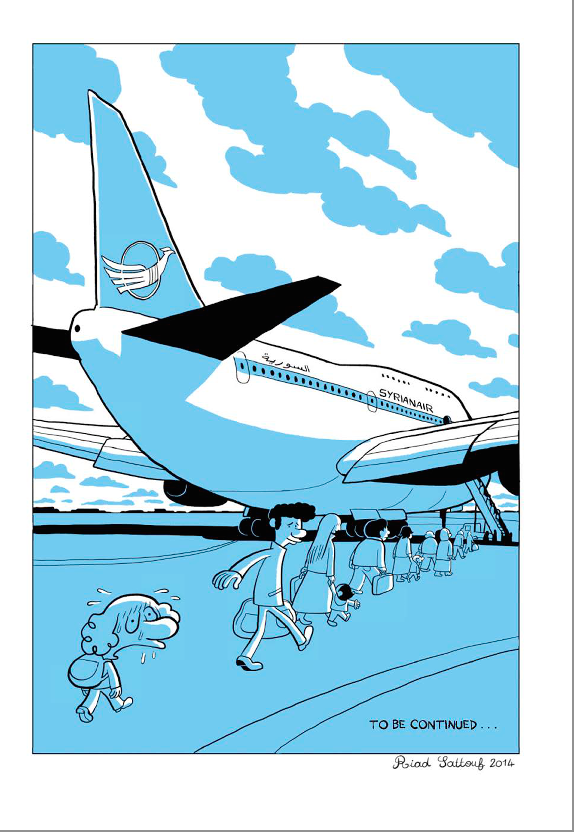

My paper on the graphic novel The Arab of the Future gained new relevance as the Syrian civil war had spilled onto Paris streets. A morose treatment of a multi-cultural childhood, The Arab of the Future is the first of a four-volume series, which has just been translated to English as well as 14 other languages. The book has sold 200,000 copies in France and won the award for best album at France’s preeminent comic festival Angoulême. More importantly, Sattouf has started new conversations about identity in Paris as well as Beirut.[1]

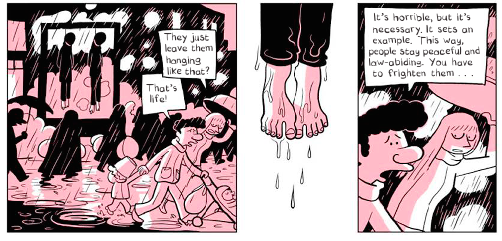

As the young Sattouf experiences government food rations and gawks at billboards of dictators, The Arab of the Future forces the reader to consider the regimes of Muammar Gadhafi and Hafez Al-Assad through the lens of a child. This vantage point offers a matter-of-fact critique of high politics, however unwittingly. For instance, on a trip to Homs, Syria, the young Sattouf witnesses a public hanging. Through this unadulterated view of state repression, one can begin to think through the broader circumstances of ISIS’s rise. Sattouf, however, smartly does not let today’s current events shroud his memories. When his family visits the ancient city Palmyra, the author does not hint at its future wreckage at the hands of ISIS. (To be sure, the book was likely written before ISIS’s escalation of the Syrian civil war. But Sattouf sticks to recollections and offers no introduction or footnote on current events.) The result is a look toward a past era in Syria, Libya and France, without projecting contemporary anxieties and avoiding nostalgia.

But, in a book that is all about that past, what does Sattouf mean by the title, The Arab of the Future? For that, I turned to the penultimate page, where young Riad and the family are in France on holiday. They take a boat to Saint Malo, the French port city, where his father withdraws thousands of US dollars. “I know the last year in Syria was hard,” says his father, a troubled pan-Arabist and occasional misogynist who is adoringly rendered throughout the novel, “but everything will be better now.” The boy is devastated. “We’re going back to Syria?” Riad yelps. “Of course,” replies his father. “The summer’s nearly over… You can’t spend your whole life on vacation! The Arab of the Future goes to school.” Which is to say that the Arab of the Future cannot remain a child forever and has to become an adult. The second volume of Sattouf’s memoir is set in Syria, where he finally goes to school.

The audience at the American University of Beirut was riled up by my choice of bringing in Sattouf. Damluji rejected my description of the Franco-Syrian artist’s work as an Arab comic, saying that by placing Sattouf in the same category of Lebanese comic artists that I was doing a disservice to local creators. “We need to be critical of it because it’s so widely read,” he said.

The comic artist Lena Merhaj argued that Sattouf’s book was flawed and racist. “I’m angered to read this comic,” she said. “It’s definitely a frame that is very much biased toward the Syrians. I know plenty of Syrians who are not violent. The way [Sattouf] shows all his cousins, all his family—I mean everybody in his comics that is Arab is violent, and I think there he doesn’t create himself as an Arab of the Future, unless the Arab of the Future is really someone like him that is displaced and then reflecting back on this childhood from a very far place, not really thinking of the audience or what kind of reaction they would have from reading that [Arabs] are uncultured, violent, etc.”

For Merhaj, to paint Arabs as pugnacious in a best-selling French book unfairly promulgates Islamophobia in a Europe scarred by Islamic terror. She also questioned the authenticity of the childhood memoir, whether Sattouf had exaggerated the negative moments of his youth: “The questions are what did he edit and how did he focus all these stories that they could show all this shit,” she asked.

“I really would like to respond to that as a Syrian, who lived that shit,” scholar and artist Lina Ghaibeh interjected. “I’m not going to claim that it was all good and that it was all wonderful and that we were all civilized…[but] I think if I have something to say about my country that I should not filter… If he wants to say it that way, then I think he should say it, and if we think otherwise then we should show it.”

“May I say something from a French point of view,” interrupted Jean-Pierre Mercier, an editor and curator at the Angouleme Museum of Comic Art. He noted that in a variety of interviews with the French media that Sattouf has said that the story is true to his memory. “There is no political background, in my point of view, when I read it,” added Mercier, drawing a parallel between how the controversial comic artist R. Crumb depicts sexist narratives without inhibition, knowing that he will offend.

I could barely get a word in, and it was the q&a session for my paper after all. When I got the chance to answer, I asked a bigger question: Why did Sattouf choose to draw this story in the first place?

I have three thoughts. First, through the simplicity of a child’s perspective, we can gain new understandings of the past and uninhibited views of the future. Telling the story from a child’s point of view is not just a tactic of cuteness, but an approach that problematizes the biases that we adults hold dear. Second, childhood memoirs are a way to work through all that childhood angst, basically an illustrated version of the psychiatric couch. Third, and definitely connected, is the search for clarity about the past. This is what the writer and theorist Walter Benjamin notes in the introduction to his book Berlin Childhood Around 1900, a series of fragmented memories of youth. “In 1932, when I was abroad, it began to be clear to me that I would soon have to bid a long, perhaps lasting farewell to the city of my birth,” he writes in the memoir’s introduction. “I deliberately called to mind those images which, in exile, are most apt to waken homesickness: images of childhood.” Benjamin sought “insight into the irretrievability—not the contingent biographical but the necessary social irretrievability—of the past.”

In exile, Benjamin did not look to the past for comfort but for clarity regarding the present and hopes for the future. Like a comic memoir, Benjamin’s recollection relies on painting specific images and leaves it to the reader to piece them together. To write about the past is to finally part with it, to find meaning in it, and thus to shape one’s own future. When Benjamin recollects his childhood, he presciently describes a way of life that the Nazis were about to erase. This is what Sattouf does in The Arab of the Future. He has captured a Syria that is now disrupted and destroyed. A return to Syria is now impossible, and to convey those stories—however gloomy they are—offers a form of defiance.

The discussion spilled out into the foyer, through a rainy walk to a nearby restaurant for lunch, and continued later on over dinner. I had read Sattouf with such enthusiasm and was surprised to be attacked and defended with such vigor. I was even more surprised that difficult questions about Arab identity—so scarcely discussed in Beirut or Cairo—came to the fore in conversations around a graphic novel.

From Beirut to Paris

The symposium had ended, and like many who return to the familiar in a moment of tragedy, I perused Arab cartoons to grasp the aftershocks of terror. Online, the first impression was unabashed solidarity in the form of the tricolor flag, which appeared on global monuments, social media avatars, and brand logos. Such viral images—often depictions of previous events or Photoshopped misrepresentations—are easy to grasp, which is why they so quickly gain social value.[2] A year ago we had Je Suis Charlie, a flat slogan of solidarity that seemed to contradict the rabble-rousing nature of Charlie Hebdo’s own cartoons, and now we had the French flag as a stand-in for camaraderie.

Stark and simple imagery is comforting because, in the wake of any attack, critical analysis is scarce. Alternatively, a handful of Arab artists composed powerful images that avoided flags altogether. By conveying the Paris siege without nationalistic symbols, these cartoonists expressed universal struggles and suffering, rather than divisive slogans.

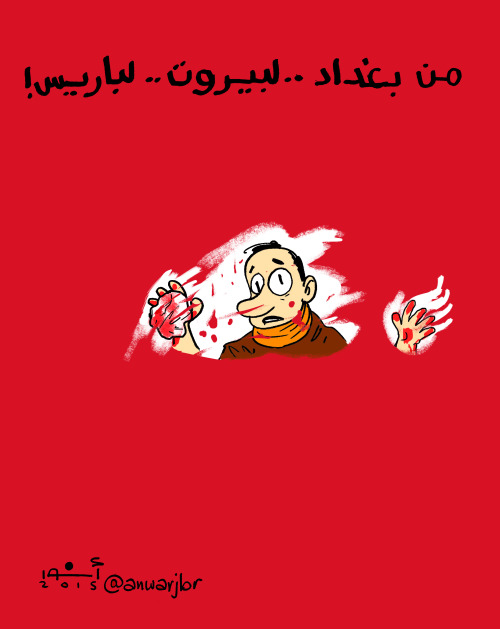

The Egyptian artist Anwar, in his November 15 cartoon for the newspaper Al-Masry Al-Youm, drew a man wiping bright red blood off of a window, which he captioned “From Baghdad to Beirut to Paris!” For Anwar, all blood is the same blood, whether it’s Iraqi, Lebanese or French. Anwar’s gut reaction to terror goes beyond speech; he offers no comment or punch line, just a straightforward image.

Three other cartoons caught my eye. In the Egyptian newspaper Al-Shorouk, Walid Taher republished a cartoon from earlier this year, in which two men are chatting; the word “Terrorism,” is overlaid onto them, literally composing their limbs. From the artist’s point of view, terrorism is simply part of daily life.

In the Iraqi newspaper Al-Sabah, Abdul Raheem Yassir drew the connection between Paris and Baghdad’s suffering. The mirror image of ISIS stabbing a man in the back has become a universal image of agony. Yassir feels France’s pain. Similarly, Le Hic, in the Algerian newspaper Al-Watan, illustrated the image of Alan Kurdi, the fallen Syrian refugee, to depict the universality of suffering. It can be read as a call for solidarity, albeit much darker than the ubiquitous images of the French flag or the Tour De Eiffel as peace sign.

An old binary seemed to have flipped. “Before the Lebanese civil war, Beirut was known as the Paris of the Middle East,” wrote the journalist Adam Shatz in the London Review of Books. “Today, Paris looks more and more like the Beirut of Western Europe, a city of incendiary ethnic tension, hostage-taking and suicide bombs.”[3] Beirut, in contrast, returned to a state of normalcy rather quickly. The terror attack undoubtedly jarred the Lebanese into considering the future of Syria’s civil war, and authorities upped security throughout Beirut. But by the next weekend, bars and clubs buzzed at a regular pace, as concert halls in Paris postponed their activities indefinitely.

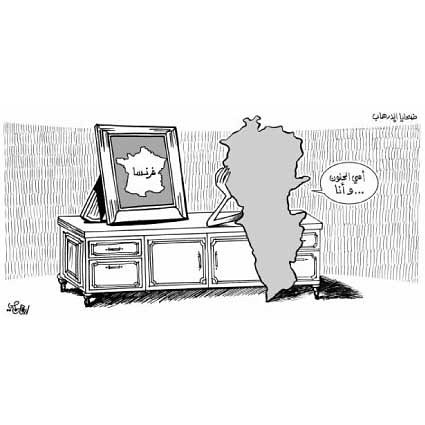

Many activist friends from the Middle East emphasized the dissonance between the Western media’s uninterrupted coverage of the attacks on Paris and disregard for Beirut’s suffering.[4] There was truth to this observation, but such criticisms were not ubiquitous. In the Lebanese newspaper An-Nahar, cartoonist Arman Hamsy depicted a map of Lebanon leaning despondently upon her dresser, looking at a photograph of France, educing the deep tie between two cities. Terror, when any place in the world is struck, has an impact globally.[5]

This thought remained with me as I explored the city’s art scene, and the multiple festivals and events that were taking place. Sattouf told the story of growing up in Libya, Syria and France in the early 1980’s, re-experiencing a difficult childhood. Themes from the illustrated memoir, such as reminiscences of lost pasts, hopes for the future and ambiguous Arab and global identities, ran through much of the art I encountered in Lebanon. Gallery exhibitions and lectures, all prepared before these acts of terror, offered original commentary on Beirut and Paris at a moment where it seemed like very little new could be said about tragedy.

Walking on Thread, Heartland, and Home Works

Art can be a way to think through violence’s many facets and effects, but sometimes, art becomes propaganda. Here I am thinking of the blunt and didactic political cartoons, galvanizing a public that is already angry at terrorism. I’ve seen this in paintings, too, notably a show at Cairo’s Art Corner Gallery earlier this summer entitled, Long Live Egypt. One painter depicted the beheadings of Coptic Christians in Libya and the Egyptian military surmounting the ISIS threat. The viewer gained little from this artist’s criticism of ISIS and aspirational thinking about Egypt’s greatness.

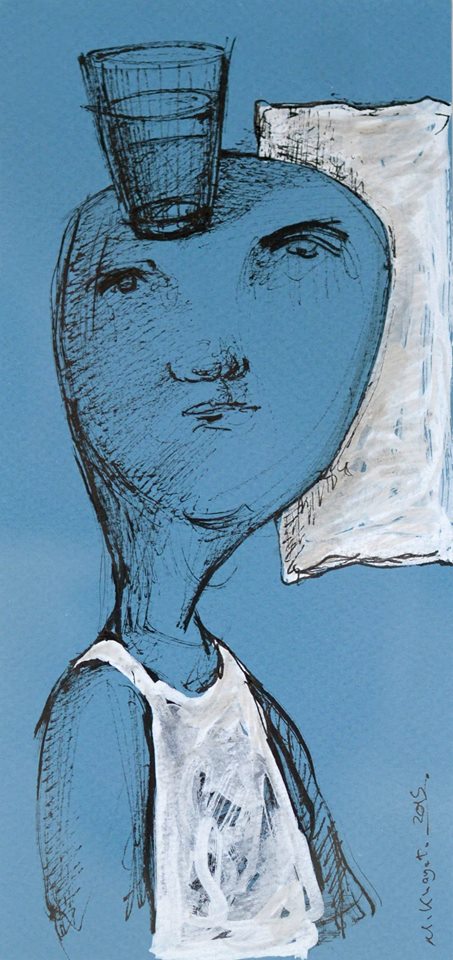

More compelling is the ability of art to stir reflection through sheer simplicity. In Beirut, the Syrian artist Mohamad Khayata’s solo exhibition Walking on Thread did just that. Displayed at 392rmeil393 Gallery in Beirut’s Gemmayze neighborhood, Khataya’s line drawings and minimalist paintings speak to the constant balancing act of refugeehood. A moon-like face, painted in a rich blue, rests on a pillow while balancing a glass of water on his head. That half-filled glass evokes the time-old question that distinguishes pessimists from optimists. Another character balances an oversized pointy bullet upon his head; in another drawing, over a dozen faces balance in a boat drifting through a sea.

I met Khayata though Karim Qabrawi, a Syrian animator also living in exile, who had attended the comic symposium and happened to be at the opening. Qabrawi, in the same Superman T-shirt from a few days prior, also introduced me to a woman who holds monthly salons in her apartment, where she and her husband had amassed a collection of Syrian art and furnishings. Her monthly gatherings provide an opportunity for displaced Syrians to experience an Aleppo-style home, something inaccessible despite Beirut’s close proximity to her guests’ lost households. Qabrawi put his arm around Khayata, and they both smiled.

The drawings and paintings on the walls around them were of families in boats, leaving their homes without even a bag. Looking at the empty landscape on which the boats floated, I pondered the fact that the very existence of hope is under attack. As Khayata told me, “We hope that there is hope.”

The lucid message of Khayata’s show contrasted with the more conceptual exhibitions across town. The Beirut Exhibition Center offered up Heartland, a group show of abstract works reflecting on Lebanon (a white map of the country was superimposed on the backdrop of the catalog). Facing the sea, the blue-chip art space is located downtown, across the street from a posh shopping mall built upon the civil war’s ruins. The installations of Heartland contained an air of pretention absent from Khayata’s works, while conjuring analogous themes. Gilbert Hage’s pigmented print of a very large pillow is enclosed in a leafy pillowcase, reminiscent of the cedar tree on the Lebanese flag. Around the corner with Lamia Joreige’s big prints of a Super 8mm film, entitled “Sleep,” is a close up of woman’s eye, shut. Walking out of the art space and gazing at the mountains afar as the sun set, I wondered if the entire Lebanese nation wanted to crawl under a pillow and hide beneath the sheets.

Meanwhile, the art collective Ashkal Alwan held its seventh Home Works, a biennale of sorts, with exhibitions, performances, talks and workshops over two weeks.[6] Both of the primary exhibitions in the space reiterated now-familiar themes: What Hope Looks Like After Hope (On Constructive Alienation), a group show curated by the Alexandrian artist Bassam El-Baroni on the first floor of Ashkal Alwan asked, “What would hope look like if we injected it with a strenuous dose of reality, placed it in a world where causes are untraceable and effects incalculable, severed it from its more eschatological concerns about the future, and blocked it from using the posturing of human rights and humanism?” The answer came in a potpourri of experimental installations and films, and a series of artist talks. On the roof on Ashkal Alwan was an installation called Blazon, in which the artist Marwan Rechmaoui had installed a wire framework to hang scores of flags representing the geography of Beirut. This critical reimagining of the city’s cartography and culture had frayed after a rainstorm and continued to blow in the wind.

Questions surrounding memory ran through Home Works, too. I attended Ode to Joy, a play directed by Rabieh Mroué, which revisits the attack on the Munich Olympic village in 1972 and might be called an ode to memory. The 65-minute production, co-written by Mroué and writer Manal Khader, both of whom acted in it, consists of a series of monologues and vignettes examining the media’s role in broadcasting the violence (the hostage situation was filmed on live television), the attack’s effects on the Palestinian revolution, and the public’s memory of these events. After two sold-out nights, Home Works added an additional performance.

Throughout Ode to Joy, the three actors’ backs face the full auditorium, and a digital camera renders them on a large screen. The performance begins with the tale of a village in which ghosts haunt residents’ beds, and climaxes with the detonation of a miniature bed. Beethoven’s melody blares as beds explode on the large screen. The bed explosions no doubt reference Israel’s covert assassination of Fatah representative Hussein Al-Bashir, who was killed by a bomb hidden under his hotel bed in Nicosia, but also relate to home, intimacy, and peacetime. I asked Mroué whether he thought twice about exploding a bed on stage following Beirut’s recent explosions. “Not at all,” he replied. “It’s nothing to do with the trauma. After all, it’s a theater piece.”

A theater piece that nevertheless seeks to unearth aspects of the Munich attack that had been overlooked, like the names of the 236 suspects detained and questioned amid the German investigation, the vast majority of whose names are illegible or absent from official documents. Photographs of PLO fighters, footage of Russian gymnast Olga Korbut, snippets of the document trail from the German investigation, and other fleeting representations appear on the large screen behind the actors. In one scene, they describe how the German police psychologist George Sieber had penned white papers noting 26 possible disaster scenarios for the Olympic games, including a terror attack (situation 21) that eerily approximated the actual events that transpired. Yet authorities had opted for a light security footprint as to avoid the associations with the hyper-security of the Nazis. It was through these seemingly prosaic details that Ode to Joy forces the viewer to reconstruct the terror in Munich based on new information and grainy images. “Ode to Joy is about the process of writing the future as a series of possible scenarios, the failure of the present to deal with reality, and the necessity of fiction to retell the past,” as the catalog stated. By retelling the past, through fiction or nonfiction, through comics or art, we can begin to explain the present. Indeed art can provide a counter-narrative of recent history—not as an attempt to contextualize or rationalize despicable acts, but rather to ask new questions, such as how the media abridges events toward obfuscation.

The show ends with a monologue about ISIS’s mass executions. The terse description of a group of men in orange jumpsuits lined up with guns to their temples conjures up vivid imagery of the group’s savage tactics that the audience knows all too well from media reports. “Suddenly, we opened our eyes and we were surprised by those so-called Islamic State and with their crimes and with their horror[ific] deeds, as if they came from the sky,” Mroué told me by phone. “But actually it’s something that not only us as inhabitants of the Middle East region but also the whole world is responsible for, this phenomena… It was something that was growing everywhere—inside our houses, our apartments, our countries, our cities, etc. etc. Everywhere.”

At one point, a live image of the audience is represented upon the stage screen, an unambiguous reminder that each viewer is indeed a participant in this event and all events.

Predictive Texts

In Beirut, I kept finding connections between my research and my environment, little signs that suggested I was on the right track. I kept returning to the paintings of Mohammed Khayata. His portraits of lost Syrian faces were similar to the best political cartoon reflections on terror in Paris and Beirut; they conveyed the struggle without flags or national markers.

On the other hand, Riad Sattouf grapples with nationalisms in The Arab of the Future, and in his graphic novel we see the mainstreaming of issues pertaining to Arab identity in Europe—issues that are rendered through a Syrian lens, but that resonate for readers from Algeria to Yemen. Sattouf gives a critical treatment to the pan-Arab ideologies of the 70’s and 80’s, movements that we today—us Arabs of the Future—seem to have forgotten, amid the rise of groups like Al Qaeda and ISIS, and the decline of pan-Arabism. As the editors of the Middle East Report put it in their new issue devoted to ISIS, “In this time of monsters, as in the fall of 2001, the weapons of the weaker are knowledge of history, empathy and common sense. There is no option but to use them.”[7]

But analyzing history is a little less thrilling than predicting the future, which is why Google’s Fortunetelling page was shared so widely this September. Once on the page, one can type a query to “predict my future.” The user finds that the space auto-filled with: “Where can I find a safe place?” “Will I be reunited with my family?” “Will humans ever stop fighting war?” etc. It was a clever ploy to draw attention to 60 million refugees. But strangely enough the crises in Iraq and Syria are not mentioned by name, and the “need [for] structural solutions on a political level for this growing European problem,” are discussed in the abstract. How can we begin to shape the future without an appreciation for what came before?

Senseless acts of violence evoke intense emotions and numbness. As my perspective alternated between the two, I found that art provided space for contemplation that the mainstream media has eliminated in its emphasis on breaking stories divorced from a larger context or historical scope. As I turned toward art and plunged myself in the present, I realized that much of the contemporary artistic and cultural contributions engaged with the past. These pieces offered a much-needed corrective at a time of knee-jerk xenophobia, as Paris licked its wounds and American politicians baited Muslims after the San Bernardino shooting.

At the CairoComix Festival in November, my dear friend and co-panelist Jad spoke of Arabs’ willing obliviousness to that which preceded: “We are a people who ignore our history.” In Beirut I realized that the Arab of the Future is the one who is willing to turn toward the past.

[1] “’The Arab of the Future’ has become that rare thing in France’s polarized intellectual climate: an object of consensual rapture, hailed as a masterpiece in the leading journals of both the left and the right.” Adam Shatz.“Drawing Blood,” The New Yorker, 19 October 2015. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/10/19/drawing-blood

[2] I first blogged about some of these images on November 15. “From Baghdad to Beirut to Baghdad,” Oum Cartoon, 15 November 2015. http://oumcartoon.tumblr.com/post/133263163726/from-baghdad-to-beirut-to-paris-blood-is

[3] Adam Shatz. “Magical Thinking About ISIS,” London Review of Books, 3 December 2015. http://www.lrb.co.uk/v37/n23/adam-shatz/magical-thinking-about-isis

[4] Even though the Paris attack was three times more deadly than Beirut’s and represented a shift in ISIS tactics, there was a dissonance between the coverage of the two events. Even the way the media described the location of the Beirut attack was controversial, which The Times acknowledged in a report: “Some blamed news coverage for the perception that Beirut is still an active war zone. They cited headlines — including, briefly, a Times one that was soon changed to be more precise — that refer to the predominantly Shiite neighborhood where the bombing took place as a ‘stronghold’ of the militia and political party Hezbollah. That is hard to dispute in the political sense — Hezbollah controls security in the neighborhood and is highly popular there, along with the allied Amal party. But the phrase also risks portraying a busy civilian, residential and commercial district as a justifiable military target.” Anne Barnard. “Beirut, Also the Site of Deadly Attacks, Feels Forgotten,” New York Times, 15 November 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/16/world/middleeast/beirut-lebanon-attacks-paris.html

[5] I discussed these cartoons with Public Radio International. “Many Arab Cartoonists Have Responded to the Tragedy in Paris with a Sense of Shared Grief, PRI’s The World.” http://www.pri.org/stories/2015-11-17/many-arab-cartoonists-have-responded-tragedy-paris-sense-shared-grief

[6] In spite of the suicide attacks, only two events of Home Works were cancelled, according to Art Forum. Kaelin Wilson-Goldie. “So You Think You Can Dance,” Art Forum, 29 November 2015. http://artforum.com/diary/id=56450

[7] “On ISIS,” The Middle East Report, Fall 2015. http://www.merip.org/mer/mer276/isis