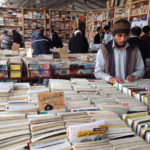

“Cairo writes, Beirut publishes, and Baghdad reads,” goes the adage. At the Cairo International Book Fair, where hundreds of publishers and thousands of readers gather each winter, everybody writes, publishes, and reads.

While the sclerotic institutions of state-funded culture remain conservative forces with an outsized role in Egyptian letters, independent publishers continue to push the limits and introduce new voices from within and without the Arab region. At the fair, you can find the latest catalogues of free presses from across the Arab and Muslim world, periodicals from a century ago, or quirky delights like contemporary children’s books from Syria or Yemen—that is, if you can find your way around the colossal fairgrounds. Since there is no map or guide—at least not one that’s of any use—let me give you a tour.

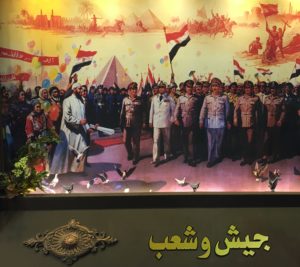

Past the metal detector and security guards, a large screen plays a video of the recently passed novelist Gamal El-Gitany, although that’s the most intellectual experience one has in the main hall. Immediately to the right is the Ministry of Defense. Inside the spacious exhibition are a few of the ministry’s military history publications and copies of Jane’s Defence Weekly. Visitors are excited to take a photo in front of a large mural of soldiers that reads, “Army and People,” in Arabic. A bronze statue depicts a soldier holding a torch, as a nationalistic anthem and video serenades the crowd. In another country, visitors might breeze past such corny displays of nationalism. Yet in Egypt, three and a half years since the military takeover, the Defense Ministry maintains an ascendant role in public life, the economy, and even pop culture.

Next is the Ministry of Interior. The Center for Research of the Police puts out occasional policy reports and periodicals, including one that boasts about the high standards of Egyptian prisons. I am not buying. Nor does anyone seem to be buying their black volumes, with titles like The Crime of Money Laundering in Comparative Law. Rather, youngsters take a selfie in front of mural of Mother Egypt against skyline of Cairo of the imaginary, with minarets, pharaonic temples and Hellenistic columns, and the 20th century Cairo Towers, near an idealistic representation of a band of workers.

Across is the Ministry of Culture’s publisher, with monographs of artists and writers that fit the state’s narrative. Then the display by this year’s guest of honor, Morocco, outfitted with traditional latticed windows and arches, painted white and gold, contrasted by the country’s red flag. As in most other stalls in this official hall, the books are for viewing, not consumption. Some folks dawdle on white chairs.

A small, unmanned stand flaunts tacky, self-Orientalizing posters from Egypt’s Tourist Authority: “EGYPT: Bigger than words,” an ironic slogan for a book fair. It features a larger-than-life blonde couple staring out into the desert; in another cheesy poster a man in traditional garb serves what appears to be more honeymooners.

Next up is Saudi Arabia, with large photographs of King Salman alongside Egyptian and Saudi flags and a lavish bouquet of white flowers; their Vision 2030 is laid out on the walls beside it. There seem to be less books in this stand than anywhere else. After Saudi, there are smaller showcases for Arab League countries and a handful of non-Arab states, with some semi-official Egyptian publishers and universities peppered in. Somalia sells stacks of vintage pan-African volumes with anti-imperial covers. Syria has Agatha Christie paperbacks in Arabic along with a selection of children’s books. (The Syrian regime’s crimes are ignored, echoing Egypt’s recent policy of tacitly supporting Bashar Al-Assad.) In between are Egypt’s lesser ministries and agencies, like Youth and Sport, Civilian Aviation, and the Supreme Council of Islam. Palestine boasts framed portraits of Yasser Arafat and Mahmoud Abbas. Kurdistan and Yemen are bustling, and their representatives drink coffee and are deep in conversation. France is packed with recent authors’ translations into Arabic. Greece offers the poetry of Alexandrian dandy C.P. Cavafy in Arabic, nearby stands by Paraguay, Italy, Tunisia, and Algeria. Bahrain has empty shelves. Oman’s display has the architectural flourishes of a mosque in Disneyland. The United Arab Emirates looks like a mall bookstore, next to Sharjah Book Authority’s slick white table and chairs out of a morning talk show. China and Russia also have stands, but the United States is nowhere to be found. Across the yard outdoors, China even has another large gazebo with an exhibition of prints and more books.

The premier hall is not about books; it is about power. Taken together, this massive gallery reflects the image that official Cairo holds for Egypt within the world community. Like a world expo, the fair projects an arrangement of nations as the official organizers, representatives of the Egyptian state, imagine it to be. It recalled a reading of 19th century fairs in Europe by the scholar Timothy Mitchell: “Spectacles like the world exhibition… set up the world as a picture. They ordered it up before an audience as an object on display, to be viewed, experienced and investigated.”[1] The permanent hall comprises those vendors the Egyptian state formally recognizes and those countries that consider it important to attend and exhibit. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates boast lavish displays. The Defense Ministry and the Interior Ministry are also honored with prime real estate. Outside of these confines and nowhere on the map, independent local and regional vendors are housed in giant white gazebos or rows of booths across the sprawling fun fair.

Most of the visitors are picking through thousands upon thousands of used books and periodicals in three mammoth pavilions of second-hand editions. It is in these pile-ups that I have unearthed exciting finds for my research (like children’s comics put out during the 1967 Arab-Israeli War) or leisure (a 1962 edition of Esquire in near mint condition). Then there are rows upon rows of Egyptian and Arab publishers of every variety, Islamic and Christian, scientific and philosophical, highfalutin culture and pulp, stuffed animals and DVDs—enough to make my heart beat fast!

“It’s like a moulid for books,” said the publisher Mohamed El-Baaly, speaking of the raucous folk festivals held in commemoration of local saints. Indeed there is no larger selection and variety of Arabic books in the world.

I went to the book fair two days after President Trump had issued his so-called Muslim ban. Six of the seven countries he singled out—Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Yemen—were strongly represented at the book fair. The diversity of Arab publishing was a sight to behold. It’s hard to believe that dozens of presses from war-torn countries like Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Yemen are still putting out their new catalogues. “That’s what I loved,” said a librarian for the British Library, visiting on an acquisition mission, “the diversity of publishers. There are so many from Syria.” Even if the topics being covered by some of these publishers are relatively innocuous—in Assad’s Syrian enclave, for instance, political dissent is not being printed—the very act of creating and distributing new books is a bold example of how expression can transcend conflict. Sure, one might argue that such publishing reinforces existing power structures. In any case, these banned countries are reading a helluva lot more books than Mr. Trump.

While the newly inaugurated American president loomed large in the international media and in cyberspace, his whopping personality was absent from the Cairo Fair. None of Trump’s books, or books about him, have yet been translated to Arabic (Hillary Rodham Clinton’s books, by contrast, have been translated and are widely available at Cairo newsstands; books about Barack Obama and a variety of American personalities are around, too.) I found it incredibly refreshing to peruse through the stands of publishers, to speak Arabic with Iraqis and Syrians: given America’s rapidly shifting political climate, these conversations felt like a small form of defiance.

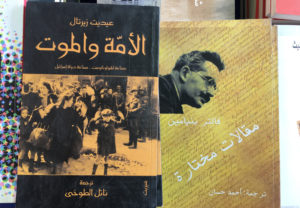

After some wandering, I stumbled upon Merit Publishing House, an Egyptian press known for its experimental novels, astute arts criticism, and compelling translations. On Merit’s table sat a translation of the Jewish/German thinker Walter Benjamin in Arabic, who died fleeing France during the war. Beside it, a book with the iconic photograph of a Jewish boy wearing a cap with his hands raised, taken in the Warsaw Ghetto in 1943. The book, Death and the Nation, is by Idith Zertal, an Israeli journalist who writes in French. The cover image provides a powerful reminder that the Arab world does read about the Shoah, and top book publishers put out books on it.

I have never heard of Zertal, but I met Nael El-Toukhy, the Egyptian novelist who had translated her book to Arabic, a couple of weeks ago. Over a late-night coffee, the gentle and mild-mannered Nael told me how Egyptian authors are not scared to address politics in their work, unlike those writing during the 90’s and early 2000’s. “The generation that is around now is very involved in politics,” said Nael, while rolling a cigarette. “Politics has also entered literature.” This brand of anti-establishmentarianism has no place in the main hall of the Cairo International Book Fair, but was on offer in the stalls independent publishers like Merit and in the pages that El-Toukhy has written and translated.

I have never heard of Zertal, but I met Nael El-Toukhy, the Egyptian novelist who had translated her book to Arabic, a couple of weeks ago. Over a late-night coffee, the gentle and mild-mannered Nael told me how Egyptian authors are not scared to address politics in their work, unlike those writing during the 90’s and early 2000’s. “The generation that is around now is very involved in politics,” said Nael, while rolling a cigarette. “Politics has also entered literature.” This brand of anti-establishmentarianism has no place in the main hall of the Cairo International Book Fair, but was on offer in the stalls independent publishers like Merit and in the pages that El-Toukhy has written and translated.

***

A few days after visiting the book fair, I met the Egyptian novelist Ahmed Naji at the Virginian Café on the Muqattam hill, which overlooks the vast expanse of Cairo and its urban sprawl. In late December, a court ordered an injunction and Ahmed was released from Tora Prison after serving ten months for “disturbing public morality.” He skipped the book fair this year, but was excited to report that next month Merit will publish his new book of short stories.

I have been closely following the political and legal implications of Ahmed’s incarceration, attending several court hearings and interviewing about a dozen players related to the case. Rolling Stone will publish my feature, based on several newsletters and further reportage, in the coming month. The magazine commissioned David Degner, a photographer friend, to snap a new portrait of Ahmed. The three of us drank coffees overlooking the dusky clouds of polluted Cairo, with its bright colors and dark shadows that evoke the post-apocalyptic Cairo of Ahmed’s prose.

Ahmed said that due to Egypt’s record-high inflation rate and the weakness of the Egyptian pound against the U.S. dollar, many Arab publishers had opted to skip this year’s book fair. Last year, for instance, a foreign publisher might sell a $10 book for about 80 Egyptian pounds; with the devaluation of the pound in November that book would now sell for 190 Egyptian pounds—and at such a high price, it is unlikely to sell at all. The fair organizers had also raised the costs for vendors. Still there were many treats to be discovered at the fair, like virtually unknown Algerian manga comics or recent translations into Arabic of American beat writers, like John Fante, put out by Saudi publishers.

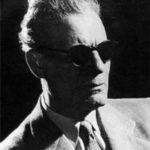

Ahmed acted like a movie star, taking on and off his black plastic sunglasses. In the camera’s flash, he looked a bit like Taha Hussein, the literary luminary who was put on trial for disrupting public morality, only to see the charge overturned. In fact, Ahmed’s lawyers drew upon Hussein’s case in their defense. The preeminent historian of Egypt, Khaled Fahmy, mentioned the two authors in the same sentence when I spoke with him by phone last month. “One could go all the way back to the famous Taha Hussein case in 1928… it’s a sober reminder that Naji is not the first, that there is a long legacy of censorship in Egypt,” said Fahmy. “But Naji really represents that generation that the revolution was about. These are the people who made the revolution and these are the people about whom the revolution really talks constantly: it’s a younger generation, its the majority of the people in Egypt in terms of sheer demographics. It’s also a different voice.” When the University of Texas Press publishes Naji’s book Using Life in English later this year, American audiences will have the opportunity to listen to him.

Ahmed is but one voice among a cohort of writers playing with form, genre and politics, in a country where publishing is vast and varied. This is a side of Egypt and the Arab world that few outsiders had taken the time to observe and ingest. If you looked carefully, it was on exhibit at the book fair, hidden among messy stalls.

[1] Timothy Mitchell, Colonising Egypt. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1988, p. 6. Available online: http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft587006k2/