TROMSØ, Norway — Since the White House cut $1.7 billion from the budget of the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) and fired a tenth of its staff in early May, headlines have understandably dwelled on the meteorological fallout: The action was a disinvestment in disaster preparedness just before deadly floods consumed Texas and heat waves blistered much of the Northern Hemisphere. But the consequences for other fields may be even more dramatic. Among them, the decommissioning of NOAA’s National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) databases, including its Sea Ice Index, has sent shockwaves through Arctic and climate research.

The impact is hard to overstate. For the past four-and-a-half decades, US satellites have meticulously documented rapid changes in global ice mass, amassing an incomparable database used by researchers around the world. In a single afternoon, without warning, that planetary archive of accelerated ice melt suddenly disappeared.

“This is a huge blow to science,” Morven Muilwijk, Norwegian Polar Institute oceanographer and climate scientist who specializes in sea ice, told me over lunch in Tromsø. “Worryingly, a lot of the world’s critical climate data is being stored in data centers in the US.”

The moment felt uncanny to me. I moved to this northern Norwegian city a year ago as an ICWA fellow largely because Arctic climate science had already been caught in the crosshairs of imperialistic and authoritarian agendas: After Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, Western countries issued unilateral sanctions on Moscow that included science cooperation. That was devastating for Arctic climate research. Instruments were abandoned in Siberia, and decades-long time series studies started logging blanks. Projects were defunded, data networks went offline and once-daily contact between close colleagues went silent. A week later, the activities of the Arctic Council—the diplomatic forum that funds and facilitates much of that science—were suspended. Practically overnight, half of the geographical Arctic went scientifically dark.

In my ICWA fellowship application, I noted that the modern era of climate science had until recently relied on a rare post-Cold War moment of optimism and a dream of polar peace. In the early 1990s, an unprecedented transnational and simultaneously hyper-regional agreement—resulting in the Arctic Council—allied the eight Arctic nations and six Indigenous organizations through cross-border research collaborations, shared data networks and environmental protection agreements. That work came to a screeching halt in 2022. Although the Arctic Council shakily resumed work in May 2023 and Russian scientists are slowly rejoining some of its key work, most research involving Russian regions and data remains on ice.

“As the Arctic emerges as a global stage for both resource competition and ever-accelerating climate crisis, will conflict or cooperation define the next era of polar politics?” I asked. I hardly imagined that the next blow to Arctic science would come from my own country.

* * *

Russia may dominate Arctic geography but the United States is its research powerhouse. In 2024, a UArctic analysis concluded that not only is it the world’s greatest public funder of Arctic research but that American institutions publish the greatest amount of content on Arctic topics and participate the most in cross-nation collaborations.

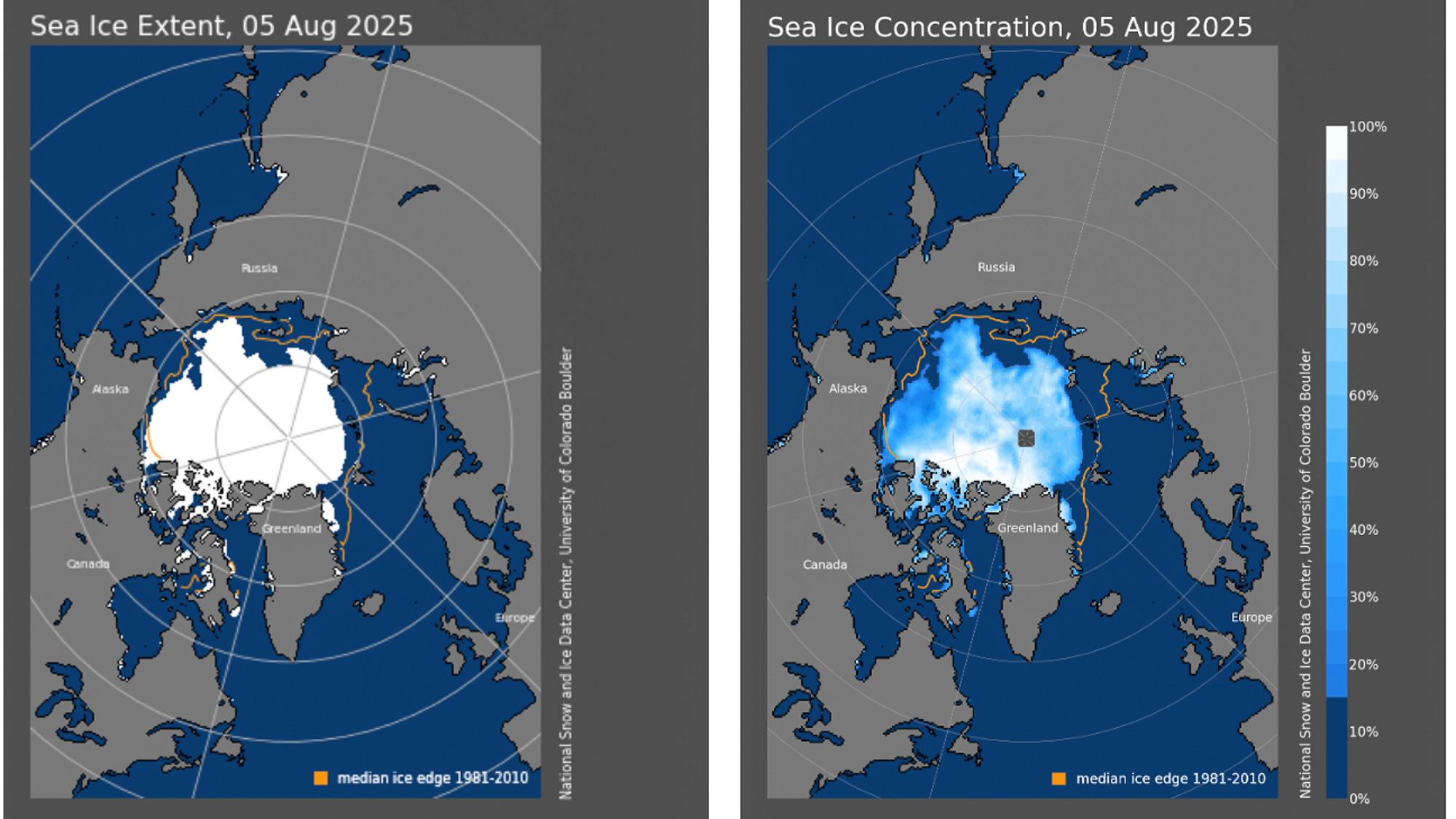

Among the stacked US Arctic research roster, NOAA is a standout. The federal agency, with six sub-agencies including the National Weather Service and the National Ocean Service, has invested billions of dollars in research that has shaped the global understanding of oceans and atmosphere. Since 1979, its fleet of 17 satellites has powered weather forecasts and helped build an archive of our changing planet. In the past two decades in particular, the Sea Ice Index has grabbed headlines not only because sea ice is an essential climate regulator but also because it’s melting much more quickly than anyone predicted.

No story of the Anthropocene epoch—the period since human activity began affecting the environment—can be told without sea ice. The planet’s icy poles are self-cooling mechanisms, reflecting sunlight and chilling the oceans as water circulates up from the equator. As greenhouse gases began to melt that ice, thousands of years of climate precedent began going haywire. Dark sun-absorbing water increasingly replaced reflective ice, raising temperatures, disrupting ocean and atmosphere circulation and prompting storms and new extremes all over the planet. Both poles matter but the high north has a lot more sea ice and is melting much faster: Arctic temperature rises are outpacing global averages fourfold.

In 2007, the Arctic Sea ice shelf collapsed, permanently eliminating 38 percent of summer ice. Since then, sea ice has become a bellwether for the unprecedented breakneck pace of climate change. The Arctic loses an average surface area of sea ice equivalent to the state of Maryland every year, and the size is trending upward. We know that largely thanks to NOAA’s satellites—although we still don’t fully understand why it’s happening so fast. Until recently, the US was leading the global race to find out: Just last year, the Biden Administration added $3.4 million to NOAA’s Arctic research fund, and more than half of that went to solely sea ice research.

NOAA was an easy target for the Trump Administration’s anti-climate science agenda. Dismantling the agency was already outlined in Project 2025, the Heritage Foundation action plan published ahead of last year’s election, many of whose authors are now in government. The blueprint calls NOAA and its agencies “a colossal operation that has become one of the main drivers of the climate change alarm agency” that is “harmful to future US prosperity.”

* * *

Ironically, President Donald Trump’s other plans for the Arctic indirectly rely on keeping accurate tabs on sea ice, not least his intention of buying Greenland for “national security.” As I wrote in The Atlantic in March, he’s interested in access to new shipping routes, resources and militarily-strategic regions—all made available because the Arctic is shedding ice at record rates.

Experts call it the “Arctic Paradox”: as ice melt makes the region more vulnerable, it has also created openings for new shipping, resource extraction and military interests. Trump’s desire for Greenland may have introduced many Americans to the opportunities emerging from the melting North. But the story had been gaining drama for at least two decades.

In 2005, an Arctic Council research group contributed its first “Arctic report card” to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, placing high North changes at the center of our climate story for the first time. In 2007, the same year the sea ice shelf collapsed, Russian explorers planted a national flag on the North Pole seabed, widely taken as a symbolic claim to Arctic energy. In 2009, a NOAA report predicted that high North melt would expose up to 40 million new tons of oil and gas by 2020.

Arctic experts cite the appearance of that report as a turning point for global geopolitical competition over the melting North. (It’s no coincidence that NOAA falls under the jurisdiction of the Commerce Department. History shows that its largest scientific investments—including seafloor mapping and fisheries assessments—have often directly informed and benefited industry.)

As a result, the Arctic Council started gaining political prominence. In 2012, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton attended a council meeting in Reykjavik; she was the highest-level American official to grace the event. In 2013, in recognition of their increased interests in the North, the Arctic Council added six new “observer states”—China, Japan, India, Italy, Singapore and South Korea—to a roster that already included Germany, Britain, Poland, France, Spain and Switzerland. In 2018, China unveiled its “Polar Silk Road” initiative, planning for the moment when an ice-free Arctic would unlock record-fast shipping routes to East Asia, North America and Europe. Once obscure, Arctic Council meetings became a key diplomatic stage in an emerging competitive zone.

When Norway took over the Arctic Council chairship in May 2023, coinciding with the suspension of the council’s work, I interviewed Norwegian senior Arctic official Morten Hoglund for Foreign Policy. He characterized the scientific cost of sanctions as regrettable but abstract. “It’s a loss for science,” he said, “but we know what we need to know in order to act.”

Climate scientists say that’s a dangerous misconception. It may be true that the expert consensus is clear and we know to reduce emissions accordingly. However, we long ago surpassed the time in which emissions reductions alone would be enough. (Global carbon emissions hit a record high in 2024, according to the World Meteorological Organization). With climate change already on our doorsteps, the best hope is adaptation and mitigation. Our greatest chance of species survival will require getting much better at predicting what exactly will happen and when. Those predictions come from climate models, and their biggest uncertainties cluster around the Arctic.

The next generation of climate modeling, Muilwijk told me, is headed in a specific, hyper-regional direction. The existing models’ power to predict the broad strokes of climate change, and even the consequences of just a few degrees difference in temperature rise, is highly reliable. But when it comes to tying Arctic changes to regional effects in other parts of the world, it will take a lot more data and a better understanding of how the complex ecosystem works.

“‘As sea ice changes, how is that going to affect Scandinavian weather?’ That’s a very different question than, ‘How is it going to affect weather in the Sahara?’” Muilwijk said. “People have very specific wishes about knowledge, and that’s really where the work is going now.”

It all comes back to NOAA, which produces some of the world’s most powerful climate models. Its Geophysical Fluid Dynamic Laboratory is responsible for two high-resolution models as well as the “Coupled Model Intercomparison Project,” (CMIP), which helps bring many different models together. Muilwijk’s team has been downloading other NOAA datasets for just-in-case “rescue missions.”

But the data alone isn’t enough. The next IPCC report will also have to rely on NOAA’s computational power, which is at risk not only from the recent staff cuts but also planned future ones. Muilwijk compares climate models to a Google product sustained by thousands of employees. “You have all these people contributing to making it better, making sure that it stays running,” he said. “If you take some of those people away, it’s not an on or off switch. We don’t know the impact.”

* * *

One morning in mid-May about a week after the NOAA cuts, I woke up adrift in a field of sea ice. I was aboard the Dana, a Danish research vessel, along with a multidisciplinary team of 20 scientists tasked with studying the Arctic Ocean’s rapid changes. On that morning, after three days of queasy northward sailing, I was roused by the craft’s surprising stillness, and opened my porthole window.

It felt like waking up on another planet. For miles around, the dark water had sprung a sudden ghostly topography: countless tall-piling, blue-glowing, lopsided structures that drifted and rotated and slowly collided with each other, hemmed by long constellated trains of smaller fragments. Some chunks were as big as sailboats, moving with heavy sloshes suggestive of great depth, dotted with dark-spotted harp seals that slipped down their backs and through narrow passage-holes. Others were flat, broad and saucer-like, and seals lolled over their twinkling, snow-dusted surfaces by the dozens. The view was breathtaking.

It was also a wake-up call. Gazing out at the innumerable, utterly unique forms, I realized that as a climate journalist, I’ve been writing for years about something I fundamentally didn’t understand. That was my own fault. Describing this ice as if it’s already gone, I had missed what it still is.

Unlike icebergs, which calve into the sea from freshwater glaciers, sea ice forms from the ocean surface and has an entirely different crystal structure. Sea ice is sea, merely in a different state. Long before it started disappearing, it was shape-shifting with the seasons, traveling fast and far with the currents. Previously, whenever I had seen photos of sea ice in fractured shards, I had assumed that the fragments represented some tragic loss. Yes, Arctic warming is devastating sea ice. But it’s always “fractured”—formed piecemeal all over the winter ocean, and then melts, mixes and moves along currents for the rest of the year. Despite its drastically depleted state, its sheer scale—and speed—is powerful beyond what I ever previously imagined. Picture hundreds of kilometers of land-like mass that can migrate hundreds of kilometers in a single day.

Our ship experienced that power firsthand. Over the course of the three-week expedition, the whims of the ice ruled our research zones: We had to check satellite data as it refreshed every 12 hours to determine where we could safely steam. (We relied on NASA Worldview data, which is more of a layperson’s product than what NOAA collects.) And that “Worldview” perspective changed my worldview, too: As the center of my inner map moved north, the patterns of ice-movement became the frame upon which I hung my unconscious internal narrative. What would it be like, I wondered, if more humans had to check on sea ice before making major decisions? And who has something to gain from the idea that it’s unsaveable?

Scientists may know a lot more than I do, but much about sea ice remains mysterious even to the experts. It’s historically understudied not only because Arctic research is staggeringly expensive but also because sea ice is a danger to the ships trying to access it. It’s also one of the planet’s most dynamic ecosystems, supporting microbes and seals and birds and polar bears, interacting with the atmosphere and the ocean, and always either melting or thickening depending on the season.

Now it’s one of climate science’s foremost challenges: With every fresh insight, it seems, we lose another Maryland-sized chunk of this critical system for our planet. “We’re getting better at the understanding and the science but as we’re getting more and more data, the system is also changing,” Muilwijk said. “You’re studying something that’s changing so fast that you can barely keep up with your own research.”

Most people will never glimpse sea ice for themselves. So it may feel hard to compare the loss of NOAA’s Sea Ice Index to, say, one of its hurricane prediction and preparedness tools. But the loss is no abstraction. Every organism will in some way be affected by what is happening to the ice in our northernmost ocean. In the vast interconnected system of global climate, the changes to this cryosphere—the part of the Earth’s surface covered in frozen water—will play an outsized role in a magnitude of catastrophes coming for our nations, cities, homes.

Sea ice is connected to all of us—and connects all of us—in our shared climate fate. We ignore it at our own peril.

Top photo: Seal-decked ice as viewed from the stern of the Dana. Over the course of a three-week expedition, the whims of the fast-shifting ice dictated its movement and research zones