At 5:30 on a dazzling May morning 200 miles off the east coast of Greenland, a small red rubber boat motored slowly though the dark cracks in a vast plain of drifting sea ice. As the craft slipped between broad floating masses, a low-hanging mist rose like steam from their glittering surfaces. Aboard the boat, four men in yellow survival suits and hard hats sat still and alert, scanning the blinding scapes for some unseen prize.

Suddenly, the smallest man aboard stepped forward and cued the engine to silence with a lifted hand. As the crew passed one slow-spinning chunk, he leaned over the rubber rim clutching a rope-strung metal hook. With a tight, powerful swing, he tossed the hook in a high arc, unspooling the rope until it plunked into the water on the opposite side. Then, patient as a fisherman, he gently tugged his line, feeling for a snag along the jagged surface.

This was Jörg Dutz, a German biological oceanographer. Slight and gray-haired with round black spectacles, he looked out of place among his younger and burlier boat companions. All were crew aboard the Danish research ship Dana, which sat anchored just a few dozen meters from the ice edge.

Jörg had come a long way for this ice: He had flown 1,000 miles from the Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research in northern Germany to the city of Tromsø, in northern Norway, boarded the Dana and sailed hundreds of miles northwest to reach this horizon-spanning ice-edge stretching out from Greenland. He was just one of 20 scientists aboard the Dana on the Atlantic-Arctic Ocean Change (AOC) Cruise, an international and interdisciplinary effort that was several years and millions of dollars in the making. Working together and in teams around the clock for 20 days, the scientists were racing to study the transformations of the rapidly warming, yet historically understudied, Arctic Ocean environment.

By some stroke of luck, I was among them. That morning, from the safety of the ship deck, I stood huddled with a group of scientists to breathlessly follow Jörg’s daring hunt for frozen game. It was thrilling, captivating and strange. In the Arctic, I soon learned, it’s also science as usual.

My previous dispatch details the Trump Administration’s recent devastating blows to sea ice research. But this dispatch doesn’t deal with data. Rather, it’s an amateur, incomplete but earnest account of what it actually means for people to go about gathering it. As it turns out, studying one of the planet’s least hospitable environments is expensive, complex, psychologically taxing and physically rough. To witness that work was the privilege of a lifetime.

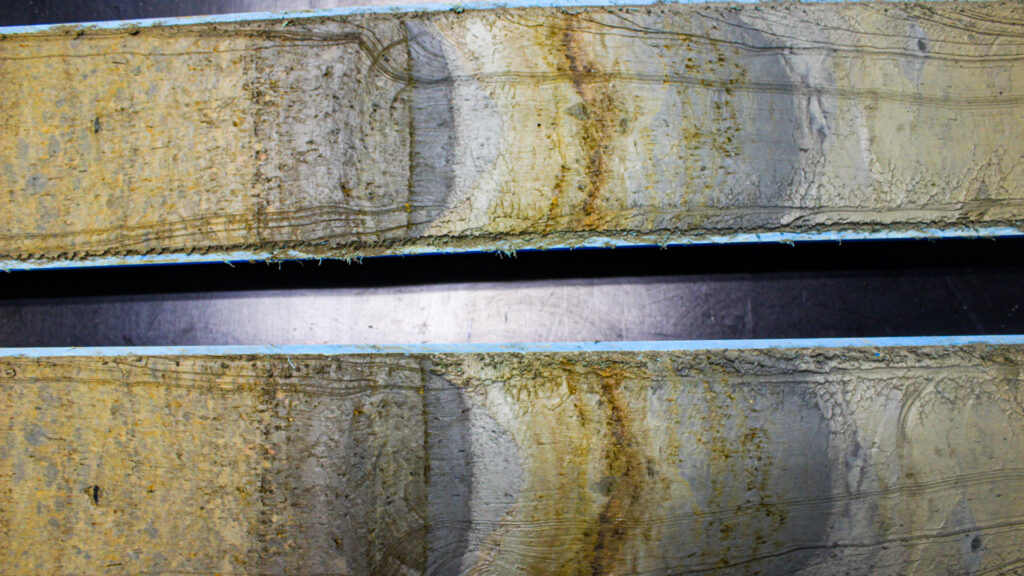

Months later, small moments from the cruise still echo and astound: A bucket filled with spinning constellations of blue bioluminescent Metridia zooplankton, recently pulled from 400 meters below the surface. The reddish hues of a first-ever topographical seabed map revealing vast canyons dredged by a supermassive glacier during the last ice age. And the suspense of a six-meter-long, deep-sea sediment core suddenly split open, its stunning geode-like layers revealing millennia of climate and volcanic activity like so many tree rings.

“How inappropriate to call this planet ‘Earth’ when it is clearly ‘Ocean,’” the science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke once wrote. That is a notion easily forgotten by the land-bound, but climate change brings it to the forefront. The United Nations describes the oceans as “not just ‘the lungs of the planet’ but also its largest carbon sink.” They generate half the world’s oxygen and absorb 30 percent of human carbon emissions. But they’ve also absorbed more than 90 percent of heat added by global warming, with consequences we don’t fully understand.

I’ve spent five years writing about climate science and one year living in the Arctic. But, as I discovered over and over during my nearly three weeks aboard the Dana, crossing an ocean that comprises more than 70 percent of Arctic geography, my worldview had been as yet—quite myopically—terrestrially bound.

* * *

Two weeks earlier, on the frigid morning of May 16, I had stepped from my Tromsø apartment with a duffel bag slung over each shoulder and walked 10 minutes down to the harbor. I was accustomed to seeing great ships temporarily towering over my town. Today, for the first time, I would climb onboard one of them: A 257-foot, 2,450-ton, blue-and-yellow-trimmed beauty stenciled with the name DANA.

I had won my berth somewhat by luck: A friend is a videographer for GRID-Arendal, a Norwegian environmental nonprofit. They’re partners with SEA-Quester, the EU-funded interdisciplinary research group that involved most scientists aboard. My friend couldn’t make the cruise and connected me instead. Technically, I brought media expertise to help document what the scientists would be too busy to capture for themselves. But, among so many scientists and sailors, I felt more like a stowaway.

At the base of a swinging ladder-gangway, I bounced my heels against the concrete port one last time, quietly marking my last terrestrial contact for the next 20 days. Then I lurched up, ducked my head under a steel doorframe and stepped into a nautical universe seemingly snatched from a Wes Anderson dream.

Built in 1981, the Dana is a relic of a past seafaring era, with warm false-wood paneling, brass lamps and telescopes, mint green bookshelves and brown leather couches, all charmingly corner-less. As I explored the many lounges and offices, a crew member told me that this ship design—with its many lounge chairs and capacious quarters—had far too much leisure space to pass muster under modern standards. This particular ship is the fourth in five generations of Danas, and is set to retire in 2027. We were making one of its final voyages and potentially its last to the far North.

Unlike many Arctic-traversing ships, the Dana isn’t equipped with icebreaking capabilities, so her hull is sensitive. We were putting lots of trust in our captain and crew, but we’d also have to be ready to save ourselves. In January, I had flown to Copenhagen for a day of rigorous “sea survival training,” donning a cold-water immersion suit and learning that not all fire extinguishers are alike. For months before that, we’d been meeting in Zooms, etching a game plan for nearly three weeks of nonstop science.

But even before we started steaming, that agenda started to fall apart. After settling into cabins and workstations, our cruise leader, the British-born Danish Technical University oceanographer Colin Stedmon, called a meeting in the mess, or cafeteria. As we gathered with coffee at wooden floor-bolted tables, he stood to make an announcement.

“We have a slight, well, rather major change of plans,” he said with what I soon came to know as a characteristic rueful smile. It had been a cold spring, he explained, and there was much more sea ice than anyone had anticipated. So we would have to shift our entire planned research area (which was supposed to reach the continental shelf, in sight of Greenland) by about 200 kilometers to the east. The ice was both an object of our study and its major obstacle.

Over the next 20 days, that became a recurring theme: When at sea, never tempt fate with fixed plans.

* * *

Day Two, 07:52. 70’N 34” Somewhere in the North Sea, steaming toward the Greenland Sea. Feel awful. So began one (brief) early entry in my ship-journal, which reached 80 pages by the end of the cruise. That day, however, I didn’t get much writing done.

The previous night, I had barely avoided ejection from my upper-deck cabin bed. This was no lullaby-rocking. I woke up sore and sluggish, as if I had overnighted in the back of a garbage truck. And, as I was step-falling out of bed, one word sprang to mind with a newly revealed meaning: ungrounded.

As I braced myself against my doorframe, I met the gaze of Sigrun Jonasdottir, an Icelandic DTU zooplankton biologist in her mid-60s, who sat brightly perched on her cabin bed directly across the hall, knitting needles in hand. (Among the ship’s many semi-militaristic rules, cabin doors stayed perpetually propped; a closed door signifies sleep.)

“You can tell by the way that people move whether they’re a local,” Sigrun said, her blue eyes crinkling sympathetically. A seasoned seafarer, she was quite at home. This was her 10th time aboard the Dana alone—or so she thinks. “I’ve lost count by now,” she told me with an easy shrug. Like Jörg, she studies zooplankton as part of the SEA-Quester team, a multi-year project not just to better understand how much carbon the Arctic Ocean sequesters but also track how that’s changing with the fast-warming Arctic.

Most researchers onboard were connected to SEA-Quester in some way. That’s unusual for polar research. Such vessels often host a hodge-podge of researchers who apply for berths (cabin-spaces) in twos and threes from a myriad of groups and institutions, all with divergent focuses and goals. But AOC was notable for its interdisciplinary and collaborative approach. In regular meetings led by Colin, they gave each other lectures, asked for constant updates and worked around each other’s schedules. The ethos was clear: They needed each other to fully interpret the flux of this understudied, fast-changing environment.

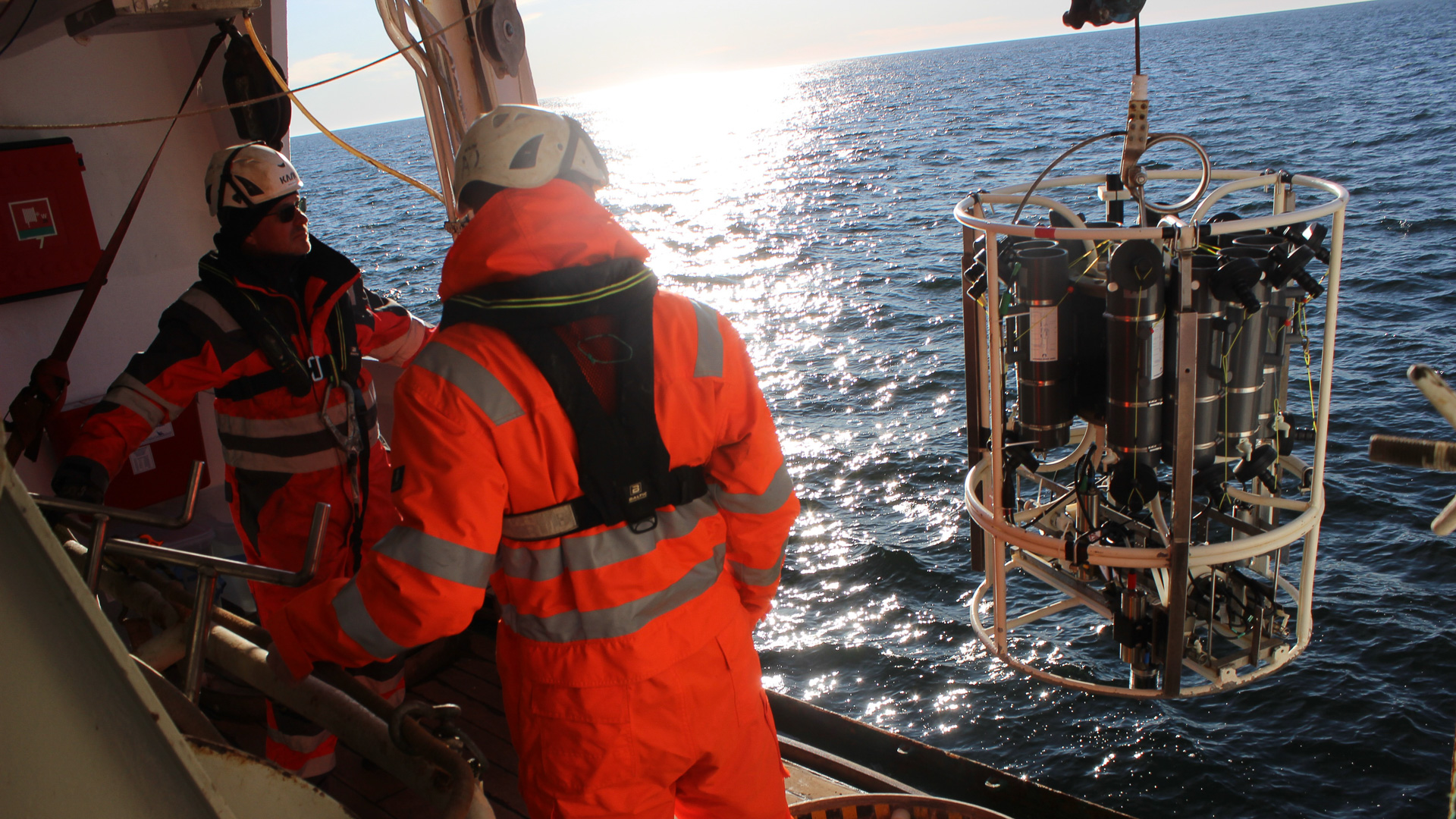

If the general work was sea-interpretation, each team had its own language. Colin’s recorded a common tongue: At each stop along the route, it sank a “CTD” instrument that measured the conductivity, temperature and density of seawater at various depths, data on which all teams relied. The Polish “bio-optics” team spoke in colors: Its members were photographing the ocean surface and analyzing light reflectivity and color gradients for chemical and biological clues. The volatile organic compounds (VOC) team was sampling seawater to read for gases, while the zooplankton team forensically counted the droppings and corpses of copepod zooplankton, the planet’s most abundant animal and the ocean’s unsung heroes of carbon sequestration.

Tracing the Braille-like text of the ocean floor, the geosciences team worked with two media. Belgian Christof led sediment sampling, plunging a six-meter-long coring instrument thousands of meters beneath the surface to sample the ancient seabed. Up near the aft bridge, German Christoph sat in front of a multicolored set of screens, watching as a hull-mounted auditory sensor created a high-resolution map of the as-yet uncharted Arctic seafloor.

I was struck by the openness, cheer and lack of hierarchy onboard. Taken together, the 20 scientists were a remarkably intergenerational assemblage, from seasoned professors like Sigrun and Jörg, to post-docs and PhDs, all the way down to the two first-year master’s students born well within this millennium.

Measured by days at sea, however, I was probably the youngest. And true to my infancy, I was still learning to walk. I’ve never taken fewer steps per day, yet each seemed to require extra energy. The body adopts a kind of wide-legged slow-motion stomp, one arm always bracing a subconscious counterweight to the inevitable sudden lurch. (The aging Dana may be cozy, but she’s also a lot rockier than modern ships.) For the most seasoned, it tends to take days for the stomach to fully adapt. During the first few days, many were missing from mealtimes, many more took infrequent gray-faced mouthfuls and only a lucky few cheerfully braced their plates from sliding while digging into heavy Danish fare.

I wasn’t the sickest, however. So at first, I wasn’t sure whether to medicate. Then on the second morning, I ran into Kira, the ship’s “Motorman” and only female crew member. Usually clad in a blue worksuit with her waist-length blond hair pulled high, she spent most of her time deep in the belly of the ship in a welder’s mask, repairing intimidating-looking hunks of metal. When I saw her, I forced a brave smile. Her brow furrowed in concern.

“Hey, don’t be tough, just take the pills!” she said in a throaty Danish accent, kindly patting my shoulder.

With Kira’s blessing, I soon started to feel a lot better.

* * *

On the fourth morning, I pulled open my cabin’s window-cover and met the unblinking dark eye of an albatross, white head half-lifted against the wind. Up close, its round body hung oddly soft and dough-like under its mastlike wings, but it took me a moment to clock what exactly was wrong.

I realized that the bird appeared legless; over its several-week long-haul flights, those unnecessary limbs stayed tucked up and out of sight. The birds became our constant companions. Long after land-bound fowl abandoned us over open ocean, a fleet of hook-winged silhouettes continued to dip and soar around us, riding currents as they raced us north.

Of course, they didn’t need to follow us—inside their brains, tiny iron filaments create an internal compass that guides them for weeks-long journeys over unbroken seas. But lacking their magnetic resonances and familiar landmarks, beyond the reach of national jurisdiction and cell service, I felt myself grasping for any orientation cues. Add the perpetual Arctic sun, and the effect could be dizzying. Space and time both seemed to alternately suspend, fuse or entirely disappear.

The ship became a universe unto itself. At any given noon-bright hour, I could wake up to a lively world of both industry and play, with scientists peering into scopes, crew charging upstairs barking Danish into walkie-talkies, rowdy card games below deck and binocular-lifting birders standing silent sentinel on the bridge. Downstairs in the small gym, next to the engine room, the whole ship had a running table tennis tournament—a particularly comical sport on rough water. (The gym’s walls were padded for safety. Using the floor-bolted treadmill meant hanging on for dear life.) Still, there was a comforting sense of community: The whole of the ship felt like a five-story working collective.

My work aboard was by far the least qualified. Wandering the decks on my own, I became the ship’s curious child, brimming with basic questions. Why is the sea that color? How can you tell a current from a wave? What’s the difference between pitching, heaving and rolling? Where are we now and where are we headed next? Why, why, why?

With every answer—usually supplied with one eye on more important tasks—I increasingly felt my extraordinary luck to be at sea with two sets of experts, scientists and sailors. Witnessing their easy cooperation, I thought about how deeply that particular relationship is historically entrenched. Anyone who attempted a sea-crossing before the era of GPS was an early oceanographer, an astute wave-reader. And as long as scientists have been studying the Arctic, they’ve relied on the sure science of seafaring to get them there.

The mutual respect was evident as the crew solved daily dramas with extraordinary ingenuity. On day three, the geosciences team realized that the cables onboard weren’t long enough for their “gravity core” to sample sediment at the aimed 3,000 meters below the surface. That could be an extremely expensive mistake. Out here, and so far north, there’s no calling in any replacements for the six-meter-long coring instrument, for which Aarhus University had likely shelled out thousands.

Then a crew member, Michael, proposed a solution. The cables may have been too short but there were two of them. He fetched a thick worn book titled (roughly translated from Danish) Seaman’s Manual. With the pages open to a rope-weave diagram, he set up on the aft deck and began a 12-hour slog of carefully unbraiding the ends of the cables—each as thick as his arm—and expertly splicing them back together.

By the end of the day, the crisis had been averted. By the end of the cruise, our core collection exceeded the team’s most ambitious hopes.“This crew is pretty remarkable,” Colin said in the next day’s science meeting, lifting his glasses to rub his eyes with the bemusement of an exhausted dad. “I think they like the challenge.”

* * *

Two weeks later, toward the end of the voyage, the morning of the ice-hunt delivered the crew its most interesting challenge yet. In fact, it had emerged in conversation in the previous days. We could sail around the ice, sure, and we could sample water and sediment alike. But what about the ice itself?

Jörg was searching for signs of life. More specifically, the kinds of ice-dwelling algae on which Arctic zooplankton rely to survive. As it turns out, the zooplankton Jörg studies play a crucial role in removing carbon from our atmosphere. After spending the summer eating carbon-rich, photosynthesizing algae, they migrate hundreds of meters to the deep ocean to hibernate. They survive the winter by metabolizing the carbon stored in their lipids, so they leave it down there, an organic carbon capture and storage process. As algae-crusted summer sea ice disappears, we still don’t know what that means for high North zooplankton—or for our climate. A rare sample of springtime sea ice, melted down and analyzed, would help us find out.

On the morning of the hunt, ice-catching proved easier said than done. Approach, toss, catch, release: So went Jörg’s methodical pattern as the crew navigated with and around the current-carried, wave-washed ice. Once, he nabbed a log-sized chunk but as the others helped tug it back to the ship, a rogue table-sized mass riding a quick current knocked hard against it, fused to its side, and carried it away. Aboard the ship deck, the crowd of scientists oohed and ahhed, clutching fast-chilling cups of coffee.

After close to an hour of failed attempts, Jörg’s hook finally stayed fast along the crest of a gleaming wedge with most of its mass buried suggestively below the surface. The crew pulled the ice-hunk successfully to the ship’s port side, where a yawning green fishing net swallowed it and a deck-operated crane screeched into action.

The ice rose with a flood of vacated seawater and slammed against the steel hull with a teeth-aching shudder. Out of the water, its sheer mass and dimension was staggering; by later estimates, it weighed about two tons. Despite our hardhats, onlookers ducked for cover as the frozen boulder swung over the deck, brilliantly scattering sunlight, then landed with a thunk, shedding glass-like fragments for meters around.

Just a few minutes later, Jörg—who had been hastily lifted back onboard—emerged from his deck-side laboratory with a meter-long steel drill. He lifted the shiny instrument high in the air and plunged it into the surface with the dramatic flair of a saw-wielding lumberjack. After a few minutes of deafening buzz, he lifted the perfectly cylindrical ice core in the air as the onlookers cheered.

“I felt like a whale hunter out there,” Jörg said, grinning and bright-eyed as he carried his sparkling sample back to the lab. “Now we’ll see what’s living inside.”

It would take three long days for the ice to melt enough for him to sample. But the analysis itself would take much, much longer. Indeed, besides one thrilling day when our seabed sonar mapper “discovered” a previously uncharted undersea mountain, most revelations have yet to emerge. Over the next weeks, months and years, stories from this voyage will continue to unfold.

I’m taking a leaf from the scientists’ playbook and accepting that the story of Arctic change has no satisfying endpoint. From them, I caught the bug of ocean-obsession: Did you know that we know less about the seafloor than Mars and the surface of the moon? That sharks have been around longer than the North Star? The more I learn, the more I feel the suspense of the still-mysterious, pulling my imagination constantly back below the surface.

Similarly, I couldn’t possibly compress an 80-page journal into a single dispatch, or even two. Now back at home in Tromsø, a bag of sea ice sits in the bottom drawer of my freezer and a small vial of 50,000-year-old Arctic seabed sediment is perched on my living room mantle. These, along with my journal and hundreds of photos, are my own archive of an Arctic Ocean in flux—a snapshot of a soon-to-be unrecognizable world.

Above all, I’m holding awe of those who work quietly at the planet’s edges and beneath its surface, on an unwinnable quest after ever-unspooling questions, ablaze with the wonder of all we still don’t know.

Top photo: Along the ice edge in the Greenland Sea, the crew disembark from the Dana ship to begin a hunt for a sea ice sample