TROMSØ, Norway — One week earlier, it had started as a rumor. A friend swore she had glimpsed it from her rooftop. Another claimed her neighbor saw it while out with his dog. From certain frosty hilltops, facing the right direction at just a hair past noon, you might have caught a quarter-slice of bleeding citrus. Otherwise, it approached only by its own suggestion, warming streetcorners and bleaching midday skies. If you watched closely enough, rose-tinted white slopes might suddenly flash gold.

For nearly two winter months, the city had been dayless. Since November 27, our eyes had been adjusting to the subtle shade-changes of an inkblot world, and we had become fluent in a vocabulary of blues. But for the first three weeks of January, midday started to split open. Day by still-night-day, that fissure thickened to a crack—leaking gray-purples, then streaming pinks, then coursing orange and rust. By mid-January, noon was ablaze like a quick-burning hearth that added fuel by the day. There was still no sun in sight. But still, something was giving us sight.

On January 21, Soldagen, or “the sun-day” marks the first time the sun reappears over Tromsø. Technically, at this latitude, the sun crosses the horizon-line six days prior. But Tromsø’s an island rimmed by mountains on all sides. Here, it takes an extra near-week of solar climbing to cross icy ridgelines and get full view of our city.

In the English language, of course, we already have a Sunday. But Soldagen is a more accurate description than how people tend to talk about this day. Often, you’ll hear “the sun’s return,” or, for the period following it, “after the sun comes back.” But those are 15th-century conceptions, of course. Whenever I found myself falling into such phrases, I had to check myself with a Copernican reminder: The sun never abandoned us. It was our own off-kilter planet that had tilted from its star.

Songbirds and seagulls: I can’t say for sure when they disappeared for the winter, but I do remember the new year’s first trills. On January 16, around 3 p.m., the snow-decked town was already midnight-dark. But as I walked by a park close to my home, I heard a lilting tune, faint yet clear. I stopped, peering through icy branches, but saw nothing. In this muted night-world, it felt as improbable as a fairy song.

On January 20, as I descended my hill into town kicking snow, I was startled by a distant cacophony. When I looked up, gulls were circling the inky sky like bits of wind-carried paper. For most of the year, Tromsø gulls, and their relentless murderous noise, are a fixture of this city. The strange stillness of deep winter must, in no small part, arise from their felt absence. I imagined these birds just days previously, warming themselves on some Portuguese coast. What do you know, I wondered at them, that I don’t?

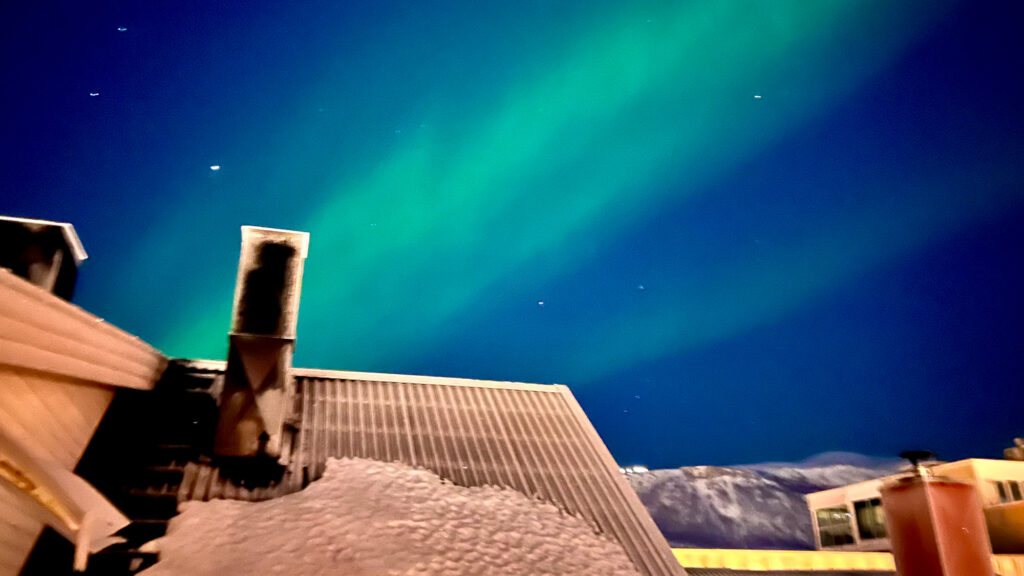

The next day, Soldagen, I awoke too early in restless excitement. As I crossed my frosty front porch at 6:30 a.m., long-tailed green auroras still laced the pitch-colored sky. Soon, sitting in my morning sauna, I looked out the window to the mountain across the sound. Through the polar night, I had become accustomed to its broad-shouldered silhouette tracing a black outline against a dark blue sky. Today, dark blue had faded to soft lilac. And the mountain was rimmed, astonishingly, in a halo of ethereal white.

At precisely 8 a.m., I walked into Risø, a local coffeeshop, just as its bearded owner Arne was firing up the espresso machine. I greeted the elderly Bjørn, another opening-time regular, as Arne began our coffees unbidden. (In the winter, I like to get in and out before the tourist rush.) Outside, the street was still dark. But as I pulled out my notebook and a pair of tourists walked in, I could hear Arne welcome them with the news: “Did you know? Today the sun comes back!”

In the north, the day marks a seminal moment. One of my northern Norwegian friends has argued that up here, New Year’s celebrations should be pushed to this day. But it has its own traditions, and of course its own treats. At the local grocery store, a poster depicting a cartoon sun in sunglasses announced the arrival of “Solboller!” (Translated to “sun buns,” it’s a charming rhyme in both languages.) It’s the day, not the recipe, that makes the solbolle; usually, it’s one of two common Norwegian pastries. One is the skolebolle, or “school bun,” a coconut-flaked pastry with a bright yellow custard center. The other is the Berlinerbolle, a filled puffy ball that Americans might call a custard or jelly donut.

It’s a rare holiday, I realized, that needs no marketing help to build anticipation. For weeks ahead of time, people had been talking about it. From long ski tours to weekday dinners, plans had been devised or delayed to this imagined sun-warmed future. Our post-Soldagen days, we dreamed, will be filled with new energy, vitality and possibility. Given our bodies’ Circadian and immune dependence on UV rays, we were to some extent correct. One morning, as I boarded the bus in darkness, I caught the eyes of a friend sitting with his snowsuit-clad toddler fidgeting in his lap. With a tired smile and a nod, his two words communicated volumes: “Next week.”

There’s no single Norwegian Soldagen; it’s a latitudinally-specific holiday. In Lofoten, an archipelago about 250 miles south, the sun returns in mid-January. On January 18 on its southernmost island of Hadsel, the sun emerges from behind a mountain and sits perfectly atop a five-foot-tall, 1,500-year-old stone monument. Archeologists believe that the monument was erected as part of a sun-worship ritual. Today, it shares the site with a church, and locals still gather annually to watch our star assume its stony throne. In Vardø, a northeast municipality only three hours from the Russian border, cannons at an old fortress fire a “sun salute” and schools close for the day. On the icy archipelago of Svalbard, halfway between Norway and the North Pole, they won’t celebrate Soldagen until March 8. But they will rejoice through the entire week, with concerts, exhibitions and nightly parties.

* * *

Last year, I missed Soldagen. I was in India for my sister’s wedding. And I felt some guilt returning abundantly sun-kissed to the still-faint blush of my wintry city. But I shouldn’t have felt so bad. It’s typical of locals to count on a trip south at some point as a respite from the dark.

But my second winter was different. This year, the sun felt particularly earned after a polar night that was both easier and harder than the first. This time, I didn’t just know what to expect—I had learned how to enjoy it. This is the cozy season, I thought, and now I had a lot more friends to make it cozier. I also felt the bittersweetness of a two-year fellowship: From one season to the next, a series of “firsts” turned to “lasts.” So, dropping into what was potentially my last polar night, I wanted to savor it.

It didn’t quite work out that way. In late November, an emergency root canal kicked off a long season of ill-fated illnesses. From then until early January, I could count my healthy days on one hand. Dunked for days beneath an endless murk of fever dreams, I learned that a polar night flu can be a near-psychedelic experience. Every time I awoke, the constant darkness signaled nothing to me. No time was passing, yet I was hurtling through the centuries, shuttling ever-deeper into a spacetime abyss.

By early January, as the grip of illness slackened, the city’s softly gathering glow felt like a metaphor for my body’s returning strength. Our tilting planet, in its long orbit, had tipped its northern face away for a season, like turning one cheek to the pillow and squeezing its eyes.

Now, with slow and heavy blinks, we were turning back to the light.

* * *

At noon, we gathered on the roof of the sauna. Pust, the local sauna company, has two floating facilities on the harbor. One of them, tall, wooden and shaped like a Lavvo, the Indigenous Sámi tent, has a ladder-accessible round roof where long benches encircle a fire pit. Today, they had set up speakers.

On the dock, wool-bundled locals collected solboller and cups of hot reindeer broth before ascending the ladder. Atop, the space was small. Still, about 50 people packed in around the blazing fire, seated on reindeer hides or leaning against the walls. More perched on the ladder just to get a glimpse of the show.

Across the fire from where I stood, a dark-haired woman sat in front of a DJ booth in a black beanie and a white lukkhá, the Sámi felted wool cape. Next to her sat an older man in a tall flat-topped hat, striped red, orange and white, and a red traditional gákti, or high-collared Sámi coat.

Charlotte, a local contemporary musician and DJ, introduced the man next to her as Ingor Nila, “one of the world’s best yoikers.” (Yoiking is a Sámi song tradition. Before the practice was outlawed as sorcery in Norway as early as the 17th century, every person and place had its own unique yoik.) A reindeer herder hailing from Kautokeino, a majority-Sámi northern city, Nila could yoik his family members back six generations. This week, he had planned to come to Tromsø for dental work. After calling Charlotte, they decided to make an event of it. Today, Nila would yoik the sun.

“The Sámi word for sun comes from mother,” Nilas said in Sámi, as Charlotte translated. “We have to honor the mother-principle as well, as the sun returns to Tromsø.”

Sitting at her DJ booth, Charlotte pushed a mixer control slowly forward. As the speakers thrummed, she began nodding her head, then turned a dial, adding an eerie echo to the beat. Then Nilas started singing. Faltering at first, then growing in strength, his melody was both haunting and hopeful. As smoke curled up toward paling skies, and effects mixed with human voice, the white mountains across the fjord began blooming gold. From up here, we couldn’t actually see the sun; a high-roofed hotel blocked our view. But its light was unmistakable.

Minute by minute, as the sky lightened to a robin’s-egg hue, new warmth flushed the cheeks around me and pale wood radiated a fresh butteriness. I had been foolish, I realized, for thinking I might have seen sunlight already this week. Awash in true day for the first time in two months, people couldn’t stop looking around at each other, stunned and smiling.

Just after 1:00 p.m., I left the sauna and walked south along the harbor, kicking kelp-threaded snow into the dark water below. Gulls circled overhead and a sharp wind tossed sea scents. As I passed cement pilings and followed the coastline’s natural curve, distant orange-basked mountains emerged into view.

Suddenly, a spear-like glare sliced across my field of vision. I glanced down, instinctively shutting my eyes. My retinas burned with twin dark thumbprints. After a moment, I raised my head again, squinting. And there it was: not just warmth spilling over the mountain, but a distinct orb floating just above it, radiating fire.

It struck me viscerally, then with a spreading warmth. This feeling, I thought, was both remarkable and entirely mundane. Last spring, I spent three weeks at sea. This felt not unlike my first steps back on solid land. I thought about those ancient sun-worshippers of Hadsel. Biologically, we were very much the same. It occurred to me that perhaps they took that biology much more seriously.

Further down the harbor, I watched dark silhouettes multiply as people gathered to take photos of the glory. To my left, a well-bundled elderly couple were shuffling toward the water’s edge. They stopped at the harbor just a few feet from me, put their arms around each other, then bumped heads and started laughing. When we turned to nod greetings at each other, their eyes glinted with orange light.

That first sun-day lasted only an hour or so. And even by mid-February, our “days” will still span only from 10 a.m. until 2 p.m. But already on this Soldagen, I felt a strange energetic spark, a feeling both new and old. As much as I could rationally understand that our planet had spent the past two months safely tethered to the sun, (and that our own south pole had in fact been basking in its unbroken light), I couldn’t help but feel as if we had strayed from our habitual orbit.

In my mind, we had spent the long winter traversing darkly gorgeous, frozen and far-flung worlds. Now, as we gratefully hurtled back toward our mother-star, its strong gravitational arms were pulling us home.

Top photo: The sun returns to Tromsø after two months of polar night.