One “is either a Cairo person—Arab, Islamic, serious, international, intellectual—or an Alexandria amateur—Levantine, cosmopolitan, devious, and capricious,” the scholar Edward Said once wrote.[1] I must be both.

One “is either a Cairo person—Arab, Islamic, serious, international, intellectual—or an Alexandria amateur—Levantine, cosmopolitan, devious, and capricious,” the scholar Edward Said once wrote.[1] I must be both.

Over the past decade, I have had a love affair with Alexandria.

Exit from the train station, and pop into a little toy taxi, a Russian-made Lada, that bounces about. Roll down the window: gaze at the fin de siècle buildings on the Mediterranean, their French windows, worn green shutters, and yellowed exteriors. The 70-year-old tram rattles past storefronts with faded Greek names.

Walk past the timeworn coffeehouses, one after another, all with the same wooden chairs facing the Mediterranean. One café is named after the Free Officers’ 1952 Revolution, another the January 2011 revolution. The city smells of shisha, strong coffee, and sea breeze. The sun glares in your face as you stare out to

sea.

What can be said about Alexandria without breathing a deep sigh of melancholia? It almost seems impossible to see the new without ruminating about the ruins of the old, or the absence of such ruins.

—Alexandria once contained the sum of the world’s knowledge in its library, and now the whole city is a dump.

—Alexandria was once the center of Belle Époque grandeur but the Egyptians ruined it.

Visiting writers too often parrot such generalizations. The clichéd “Alexandria in decline” narrative rests on a sunny view of semi-colonial Egypt. The notion of cosmopolitanism further reinforces it. “In the Western imagination Alexandria has always been associated with loss,” writes the historian Khaled Fahmy.[2] Let us then visit Alexandria in search of recovery.

Mass Alex

As I write this, the New York Times published just such a nostalgic headline, “Returning to Egypt’s Heart, Once Grand, Now Crumbling.”[3] Once again, the past clouds the view of the present. In fact, I had just returned from a night in Alexandria, where I saw the experimental works of the next generation of artists.

On November 24, three hundred people mingled in the basement of the city’s Miami neighborhood for the opening of MASS Alexandria. There are a dozen large-scale installations, a slew of digital art pieces and short films, and scenes of naturalist expressionism. Upon entering, one sees photorealistic paintings of a woman taking a selfie. Under a vitrine are newly embroidered tapestries with unearthly animal shapes. The smorgasbord of immersive experiments would have fit in Beirut’s top art spaces or in Europe. These are the final projects of students from the MASS Alexandria program.

In 2010, Wael Shawky started an alternative art program called MASS Alex. Shawky himself is one of the most prominent contemporary Egyptian artists, who has burst onto the international scene and exhibited his Cabaret Crusades puppet experience in blue-chip museums. He guides MASS Alex, but each year a different artist or curator designs a unique set of programming. The program took a hiatus from 2013 to 2016. There were fears that the draconian foreign funding laws might put them on the authorities’ radar. The broader political crackdown could put any independent space at risk. MASS Alex re-launched in 2016, this iteration being a seven-month multi-disciplinary experience led by German curator named Berit Schuck, who has spent the year teaching twenty young artists. “Not to teach in the old sense of the word, but to support and encourage our students to find their own language,” Schuck told me in August over cappuccinos at Délices, a century-old café on the downtown corniche. She described MASS Alex as a revolution. The stuffy art program at Alexandria University only teaches in the traditional sense: drawing, painting and sculpture.

During that trip, I visited their basement—a clean white cube of 470 square meters—to attend a guest lecture. The speaker, with a thick beard and shaven head, spoke to the twenty students and a dozen guests from the community about how the concept of borders and nation-states informs his experimental film practice, steeped in theory. Speaking in Arabic, he discussed Jacques Derrida’s notion of the foreigner—that outsiders necessarily do not understand the legal language of their adopted society. “This is where the question of hospitality begins: must we ask the foreigner to understand us?” writes Derrida. What seemed to be an abstract bout of academese proved its relevance. I stepped out to make a phone call and bought an espresso at a corner café run by Syrian refugees. Alexandria is, and has always been, a city of foreigners. In the 1930’s, Egyptian artists invited European painters and writers to come here to escape fascism in Europe. Alexandria was a city of refugees then, too.

At the Mahmoud Said Museum

“Please,” says the first guard, offering me a biscuit, which I politely decline. “Take your money and your phone, but no photos inside,” says another guard, who lets me put my tote bag on a shelf in the back office. I look up and see two handguns hanging in a glass cabinet; they are dusty, like everything else. The first guard scrupulously writes down the information from my passport into the log, even though the entry is free. I enter through a metal detector of questionable utility, where two more guards sit in a verdant courtyard, facing Mahmoud Said’s villa, which itself used to be the Prime Minister’s. Behind the two-story beauty are the tall glass towers of the Four Seasons, once the site of the city’s majestic San Stefano Hotel. Today’s remodel looks like straight out of Middle America.

Mahmoud Said (1897-1964) is Egypt’s painter. He invented a national style, his realistic portraits and ethereal landscapes translated and transformed European techniques into the Egyptian milieu. He began his career a judge and ended it a much-lauded artist. He was scarcely known outside of Egypt until 2010, when his painting “Les Chadoufs” sold at Christie’s for US$2.4 million, at the time the highest ever for an Arab artist. Since then, he has been highly sought after by international museums. It’s only here in Alexandria that dozens of his works are displayed together.

On the villa’s porch is a plaque: a dedication from Hosni and Suzanne Mubarak—the deposed president’s name is still there, even though his face is seldom shown these days in the official nationalist imagery.

In the villa’s lobby are 20-plus medals that Said won in his lifetime, including a large key to Alexandria, in case the art didn’t speak for itself. On the right is the massive “Inauguration of the Suez,” painted in 1946-47, a rendering of all the official guests and dignitaries. There are self-deprecating self-portraits of a skinny Said. Squirrelled away in a single room in the back are six large canvases of nudes; they would look typical in any museum, but hiding them in a single room makes them look pornographic. The indecency, however, concerns his objectification of the naked models, who are all dark-skinned Egyptian women with accentuated African features, often painted with their eyes closed and in languid poses. Meanwhile, the clothed women of the upper class sit upright with poise in the glamorous oils of his wife and family. The back gallery becomes the expression of Said’s id. In another room are his brushes, his easel, dozens of paint tubes, and a vitrine of personal effects.

In the basement, behind lock and key, is the Alexandria Museum of Modern Art. The rooms of modern and contemporary Egyptian greats are stuffy: Here you can see beautiful abstract compositions by the late modernists Fouad Kamel (1919-1973) and Ramses Younan (1913-1966). The seminal work by Abdel-Hadi Al-Gazzar (1925-1966), “The Key of Time”: features a mystic with grotesquely large fingers seated at a table upon which rests a skeleton key on a plate. Behind him is a funeral procession in a labyrinthine, historic district. It’s a bizarre and potent piece that international museums would kill for, and here it sits in humidity and squalor. It’s a crime to treat fine paintings this way.

Two more of Gazzar’s pieces hang in Alexandria’s Fine Arts Museum, yet his most important canvas—“High Dam Man”—has been missing for a decade. A national treasure and expression of the anxieties surrounding technological advance, it might have been burnt in the Egyptian revolution, when protesters torched Mubarak’s National Democratic Party Building. Or it might have been the victim of larceny. Gazzar himself was born in Alexandria. The next day I set out to find his family home.

The circumference of downtown Alexandria is where visitors stay, but the architectural gems continue far out into the periphery, the same green shutters, the same dust-hued buildings with hidden flourishes. This is a city of balconies, with carved designs that are pillars or art deco, facing the sea, dangling rugs or laundry, heads sticking out windows, a historic city interrupted by heinous glass boxes, like the inaccurately named Royal Alex Hotel, with its faux pillars and rosy fake granite glass facade that rises 10 floors above all its beautiful beaux arts neighbors.

My walk to Gazzar’s family home leads me through the backstreets of an out-of-use mercantile building and then the Friday Market, which goes on for blocks. In this meticulously ordered graveyard of commodities, toilet seats and other household objects are given a new lease on life. Grills, treadmills, candles, statues and teapots, motors, mannequins, clocks, fans, televisions, washing machines, microwaves, all meticulously stacked.

Another 30 minutes of walking: Two men—one young, one elderly, both smoking—are sweet enough to direct me to the street I am searching for. They do think it’s strange that a foreigner is coming all the way here to see the home of a person they’ve never heard of.

It’s a simple street. In anticipation of the approaching Eid holiday, there is a pen of sheep waiting to be slaughtered. There are people sitting in the storefront that might have been where he lived, rabbits and chickens for sale. There is excrement from livestock in the street and a kid riding a two-wheeled motor cycle and wedding places and a church and a little cellphone shop that is closed.

Gazzar’s father was an Imam. During his childhood, the young Gazzar moved to the popular Cairo neighborhood of Sayeda Zainab, an area known for its mystical traditional and rites. “Let me live in the world of magic I admire,” the artist once said. “I do not want to know what things are. Knowledge renders life unbearable. This is because the interpretation of knowledge is attainable in the subconscious alone.” Gazzar’s world of specters and folklore is a counterpoint to the once glorious Alexandria library, where all the world’s wisdom was ordered and preserved.

Whose Cosmopolitanism?

What is this cosmopolitanism that the nostalga-holics yearn for? I have long thought it a code word. Not the black and white photos of flappers but the Armenians, Greeks, Italians, and Jews, to name a few—anything non-Muslim, it seems, can be associated with cosmopolitanism. The word itself obscures. Cosmopolitanism might have been good for the foreigners or the wealthy. But what about the others?

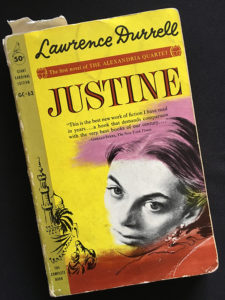

The antique shops of Fouad Street and the Qatarin distinct are the accidental public archives of those so-called golden days, shops that hum into the late evening—not with customers mind you, but with the conversations among shopkeepers and old friends. Here you might find unfinished paintings by characters from Durrell’s Quartet; there is Justine’s oil of a pirate, I swear I found it yesterday hanging in a dusty antiquerie. Everywhere are the objects of the rich and famous—China from China, rugs from Persia. One of the shops on English Church Street is called Au Petit Musée. For there is no Museum of the city’s modern history, and the only thing that comes close is a room of the king’s flatware in the Alexandria National Museum. The next shop sells century-old safes and filing cabinets. Outside men repair rugs and chandeliers, others smoking cigs or reading Quran. There’s an alley where engraved, wooden doors lean, waiting to be repurposed.

My eyes scanned through thirty dingy antique shops, seeking a work that would tell another story. What I found was immense French landscapes in gilded frames, or British characters smoking pipes, and occasionally oriental pastiche. I find myself wanting a painting of a tiny sailboat navigating treacherous waters, if only for that ostentatious frame! Or a gypsy guitar player or the topless woman reaching for a bottle of liquor. The paintings are mostly unsigned and undated, so I use my imagination, maybe one of them even hung in the late poet C.P. Cavafy’s shabby office.

I take a cab to the Cecil, a splendid hotel on the Mediterranean. In fiction, it’s where the protagonist of the Alexandria Quartet first spots Justine. In reality, Mohammed Ali, Josephine Baker, E.M. Forster, and Winston Churchill are counted among its eminent lodgers.[4]

In April, Surti and I sat in the hotel’s discotheque, just the two of us alone, as the DJ blasted techno. Churchill might have once dined in the ballroom, but that night we were treated to a private show of the loudest and most unremarkable electronica.

So you want to dance the way the old-time cosmopolitans used to? In August, I ambled to a milonga—a social dance for tangueros and tangueras—at the hidden Jesuit Center. On the second floor, eight couples electrify the dance floor, a dozen more gossip under chandeliers hanging from a crimson and gold ceiling. A couple announces their engagement, and a waiter brings out plastic glasses of sherbet on a tray for a toast.

I step outside at 1am looking for a snack, and walk past new complexes of upscale local fast food on Fouad Street (which has been a thoroughfare since the Ptolemies)—or the Greek Club. Yes the Greeks, the Greek names can be seen across the city on bronze plaques and storefronts, shops of tailors and drycleaners and cafes. Or Cap D’Or, opened since 1908, which has a marble bar, three-legged stools, a framed photo of Sadat, and so many boats hanging from the walls and in the window. The same music plays on the radio here that has played for 50 or 60 years.

Off goes the radio. A man in a burgundy jacket begins strumming an oud in the corner. I’m halfway through my Stella beer. Maybe it’s okay to be nostalgic in this bar, isn’t it? I would sing along with the oud player if I could (“Goodbye, sweeties,” he wails in Arabic.) The knockoff Egyptian whiskies on the shelf look real, but that black label is not of Johnny Walker’s, the Chivas is Royal not Regal.

Alexander the Mocktail

So much of what I know of Alexandria today is from a young scholar named Amro Ali, who has tirelessly worked to revive the intellectual community in Egypt’s second city while writing his dissertation on the topic. He’s collaborating with the Swedish Cultural Center to host a series of seminars. When I visited in August, he took me to Cabina, an independent art space where a film was screening upstairs and a band was jamming in the basement. It is next to a recently demolished Golden Age movie theater, Rio Cinema. The corporate developer Stanly—which has built tasteless bridges and towers across the city—wants to build a shopping mall in the place of the classic Cinema. Cabina has been forced to move across town, too.

But even Amro, in his attempt to revive the city and shake off Alexandria’s stifling sense of nostalgia, invariably falls into nostalgia for another era, whether it be the Hellenistic academy or for the intellectualism of the turn of the century.

There is a quote from the literary critic Fredric Jameson that I often turn to. “There is no reason why a nostalgia conscious of itself, a lucid and remorseless dissatisfaction with the present on the grounds of some remembered plenitude, cannot furnish as adequate a revolutionary stimulus as any other,” writes Jameson in Marxism and Form.[5] This quote is a useful provocation for my nostalgic little lover named Alexandria.

Rather than grumble about lost cosmopolitanism, let’s critically reflect upon it. Durrell is lovely to read on the train, but I find his distaste for Egyptians—of all things Arab, that is—to be gloomier than anything lost. Even in those glory days, Durrell was nostalgic for the days of Cleopatra and Alexander. “Capitally, what is this city of ours?” asked Durrell on the opening page of Justine, the first volume of his Alexandria Quartet. “What is resumed in the word Alexandria?” Speaking of the interwar period, his is a city of “a thousand dust-tormented streets.” What a grump. When he returned in 1977, he described a city “sunk into oblivion.” His proof: “Everything is in Arabic; in our time film posters were billed in several languages with Arabic subtitles, so to speak.”

I stop again at Délices to take my morning cappuccino, and opt not to order one of their fresh juice virgin cocktails with delectable names like King Farouk (kiwi + guava + mango) or Alexander the Great (coconut milk + pineapple) or Sultan Hussein (orange + carrot) or Hatshepsut (mint syrup + sprite) or Cleopatra (strawberry syrup + sprite).

The reconstructed citadel is a distant sandcastle, Qaitbay’s last stand in a big ole blue expanse. The black and yellow cabs, the Ladas, pesky little hunks of junk that are flies in a city that has a 20 kilometer corniche. Next to Omar Effendi, long ago nationalized and still a relic of the cosmopolitanism of consumerism from some time ago. The Tourist Office, with no computer at all; when Surti and I sought out the Biennale in 2014, they were paging through coffee-stained binders trying to find some information and alas there was nothing. Dar El-Maaref bookstore, with its shelves of dog-eared crime novels and translations that themselves belong in a museum for their cinematic covers. Alex Bank had taken over the old Italian Consulate on the sea, a sad story if you ask anyone, but at least the building will be preserved (in spite of the tacky sign). Couples eat cake at the Imperial Café, which opened in 1939.

My train back to Cairo doesn’t leave for an hour, so I wander to find Durrell’s villa, which is one of a handful of rotting, vintage constructions on a busy residential street. I took a few pictures on my phone. There is no marker or reference to its significance. I should have asked the man drinking a tea and smoking shisha in front of Villa Ambron, where Durrell wrote (not the famed Quartet), whether he knew about the building’s history. It’s for the best that I didn’t. I walked past the busted gate of #19 but decided not to venture further when I saw that families were living in the carriage house behind. Best to let them, to let everyone, be.

On the route back, on a minor square, I see a Lego-looking monument, commemorating President Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi’s 2014 visit to the city. It’s utterly bland.

It’s not that Nasser or Sadat set a match to the city; it’s not that it lost its cosmopolitan character overnight. There is no loss of Alexandria. It’s just that 2,300 years of history is a heavy burden. The falsehood often perpetuated is that the Arabs destroyed the library when they conquered the city. In Alexandria: A History and a Guide, Forster notes that the Christians had wrecked it.[6] A lesser known and less sexy narrative, however, is that the decline of the library was due to disuse.[7] Alexander’s library was filled with papyrus texts and with time, as technology changed and readers switched to folding books, the library’s fragile collection of 500,000 papyrus texts was of little function. This un-dramatic narrative holds currency for Alexandria today.

[1] Edward Said. Reflections On Exile: And Other Literary And Cultural Essays (Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2002).

[2] Khaled Fahmy. “The Essence of Alexandria,” Manifesta Journal #14 (January 2012). http://www.manifestajournal.org/issues/souvenirs-souvenirs/smell-alexandria-archiving-revolution-0

[3] Diaa Hadid. “Returning to Egypt’s Heart, Once Grand, Now Crumbling,” New York Times (November 29, 2016). http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/29/world/middleeast/alexandria-egypt.html

[4] More on the Cecil’s history can be found in the delightful Grand Hotels of Egypt: In the Golden Age of Travel by Andrew Humphreys (Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 2012).

[5] Fredric Jameson, Marxism and Form: Twentieth-Century Dialectical Theories of Literature (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1974), 82.

[6] Of note for ICWA lore: the first name Forster mentions in his acknowledgments is “Mr. George Antonius, for his assistance with those interesting but little known buildings, the Alexandria Mosques…” Antonius went on to serve as an ICWA fellow from 1930 to 1942.

[7] “The Library of Alexandria,” BBC Radio 4 (March 12, 2009). http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00j0q53