TBILISI — Walking through the leafy streets of the Vera neighborhood, Marko, an exiled Belarusian musician in his late 20s, described what had been tormenting him for months. In March, his father was violently detained by the Belarusian authorities in their hometown and thrown into a pretrial detention center infamous for its brutal human rights abuses.

A few weeks later, awaiting trial on charges of “insulting the president” for comments he had made on Telegram, he died under suspicious circumstances. Officials described the cause as “coronary heart disease” but Marko fears the truth about his father’s death may emerge only when the strongman President Alexander Lukashenko’s regime crumbles.

Marko—tall, slender, with a blond beard and corduroy cap covering his buzzed head, and who asked for his real name to be changed because of security concerns—is among thousands of Belarusian exiles still haunted by the actions of their government even after leaving their country in recent years. Whether by the detention and interrogation of friends and loved ones back home, new criminal charges and trials in absentia or a 2023 halt of passport renewals abroad, the Belarusian authorities are finding ways of persecuting citizens abroad.

Since Lukashenko’s 2020 reelection in a rigged vote and the crackdown on pro-democracy protests that followed, some 500,000 Belarusians have fled the country. The initial wave escaped the violent persecution and witch hunts targeting political opponents. Many sought refuge in neighboring countries such as Poland and Lithuania, which eased visa restrictions and granted humanitarian and refugee status to thousands.

More left in the following years as the government expanded its surveillance and intensified its search for opponents. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022—which Lukashenko abetted—prompted another major exodus. Many who left in 2022 said they could no longer live under a government that was complicit in Russia’s aggression.

Like Marko, thousands came to Georgia because of its visa-free regime, joining the swollen ranks of Russian anti-war emigres. However, unlike their Russian peers, many of whom continue to travel into and out of their home country, Belarusians face sophisticated surveillance methods by their government, making their exile more permanent.

Still, in relative safety abroad, Belarusians have begun forming communities and networks. And they are reassessing their national identity in the context of Russian colonialism and reclaiming their native tongue, long suppressed by the Lukashenko regime.

Belarusian identity or lack thereof

Many Belarusian activists say the Kremlin used the 2020 protests as a testing ground for new methods of quashing demonstrations and dissent in Russia. Reports surfaced that Russian agents were among the masked riot police and special forces troops beating and detaining protesters in Minsk. When the Belarusian government asked Moscow for aid at the height of the 2020 protests, the Kremlin gave Lukashenko a loan worth $1.5 billion.

“They would test the limits of what they can do to people in Belarus first before unleashing the same tactics on Russians,” Katia, a Vilnius-based activist who fled Belarus in 2022, told me over a Zoom call. She spoke on a day off from her job as a courier. Purple streaks colored her hair and she chain-smoked hand-rolled cigarettes throughout our conversation.

In many respects, the political trajectory of Lukashenko—Europe’s longest-serving president who consolidated power since taking office in 1994 through a series of controversial reforms—can be viewed as a template for Russian President Vladimir Putin’s. Much of Lukashenko’s rule has also been defined by a curated medley of Soviet autocratic symbolism.

When he first came to power after the collapse of the Soviet Union, he swapped the white-red-white Belarusian national flag—originally of the short-lived independent Belarusian Democratic Republic dissolved by the Soviets during the Russian Civil War of the 1920s—for a new state flag that resembled the flag of the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic. He also retained Russian as one of the two official languages—used in both government and corporate workplaces—and, like Putin in Russia, reinstated the original Soviet melody to the national anthem in 2003.

In the early 2000s, many Russian liberals and Western leaders still saw an ally in Putin, with hopes that he would continue to democratize Russia and integrate into the West. By 2003, however, the Ukrainian political scientist Taras Kuzio was already describing Lukashenko as “the quintessential Soviet Belarusian patriot who presides over a regime steeped in Soviet nostalgia.”

The reversion to Soviet-style dictatorship entailed the continued suppression of Belarusian national identity. Belarusian language and literature are still taught in schools only as separate subjects, while all general courses—from mathematics to history—are taught in Russian. Roughly a quarter of Belarus’s population uses the native language daily. UNESCO’s World Atlas of Languages categorizes Belarusian as “potentially vulnerable.”

In 2022, a Belarusian publisher spent a month in prison after attempting to open a Belarusian-language bookstore in Minsk. Efforts to revive the language through practice groups have been conducted clandestinely.

Marko says he and his late father were always aware of the repression of their culture and language. “Belarusian was always considered the language of kolkhozniki,” he told me, employing a Soviet-era term for collective farmers now used derogatorily to describe something backward and lowbrow. In the country’s major cities, he said, Belarusian hardly existed. “When we were young, we didn’t really conceptualize that [favoring Russian over Belarusian] was somehow a loss of identity.”

But in exile, the language has seen something of a revival. After 2020, Katia said, more Belarusians of all ages began speaking their native tongue. “It felt like something of a renaissance,” she explained. “Artists would tap into national motifs, books were being published in the language, stand-up comedians were telling jokes.”

Belarusian exiles in Lithuania and Poland have left a strong mark—opening cultural centers, bars and language clubs, as well as hosting Belarusian pagan music festivals.

The 2020 protests

The protests against Lukashenko’s rigged reelection erupted after the independent election watchdog Golos concluded that the opposition candidate Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya won a 56 percent majority, debunking official results giving Lukashenko overwhelming victory. She had run a last-minute campaign after her husband, Syarhei Tsikhanouski, was imprisoned on trumped-up corruption charges.

Inspired by another would-be opposition presidential candidate named Viktar Babyryka, who said Belarusians’ voices had been “stolen,” Katia became one of thousands of protesters who came out against the regime.

Babyryka was also arrested on fabricated money-laundering charges. In April 2023, reports emerged that he had been tortured in prison, and since then he has been held virtually incommunicado, as have several other opposition leaders. International human rights organizations have characterized those instances as “forced disappearances.”

Katia was caught up in some of the most violent moments of the crackdown, inhaling tear gas and struck by stun grenades. “We felt like we were at war,” she said, “although we all came out peacefully to show our numbers.”

The protesters eventually split into two camps, those who called for an end to the demonstrations—feeling violence and imprisonment were too great a risk—and those who continued to believe nonviolent resistance could force change. Living in Moscow at the time, Marko belonged to the former camp. “I have many questions for the Belarusian opposition who continued to urge us to go out even when faced with such brutality,” he told me. “How can you nonviolently protest when the police are using actual weapons against people?”

“All those people who wound up in jail or disappeared could have been free instead,” he added.

While it is difficult to confirm exact numbers because the Belarusian government keeps such information under wraps, various independent estimates say roughly 30,000 people were detained and jailed, over 1,000 injured and a few killed.

Another exile named Ilia, 23, who owns a Belarusian bar in Tbilisi, also felt nonviolence was the wrong strategy. A self-described former football hooligan and petty criminal from Minsk—robbing drug dealers in his young adult years—he recalled that he and his friends would put padding underneath their clothes during the 2020 protests, ready to fight fire with fire.

But eventually a leg wound he incurred while running from the police put an end to his protest activity. The following morning, while he was getting his wound checked at a clinic, nurses received a call from police who had already been informed that a person with his injury was there.

Asked whether he had been demonstrating the previous night, Ilia lied to the police, saying he had been injured playing football. After leaving the clinic following his narrow escape, he stepped away from activism, keeping his head down and working in bars until he left Minsk in 2022.

For many Belarusians after the protests, the capital remained a “golden cell,” as activist Katia called it, with a booming service sector, underground music scene and emerging tech jobs. Even after the crackdown, Belarusians like Ilia felt that life would remain tolerable if they stayed away from politics.

However, Katia felt continuing to protest was vital. “Nonviolent protests were the best decision,” she said, “and that is perhaps why they lasted so long and gave our cause visibility in the West.”

In addition to playing a role prompting many European countries to ease visa requirements for Belarusians, the dissent gave people “a new identity,” Katia said.

Arrests

In the months and years since the protests, the Belarusian government has continued its persecution of dissidents, using sophisticated surveillance methods to track and punish the 2020 demonstrators and their supporters and stamp out any ongoing activism.

Still, even after the crackdown, Katia continued to engage in what she described in Belarusian slang as “partizanits” work, drawing anti-government graffiti and other small, clandestine acts of protest carried out in masks. “We wanted to continue to strain the system and also keep visibility up,” she said. “As long as photographs of Belarusian protesters seeped into the media, more opportunities would open up for those in exile, as Western countries saw that things had not gone back to normal.”

Although she had been detained on numerous earlier occasions, Katia’s first major arrest—which resulted in a 15-day jail sentence—came in 2021. The authorities grabbed her at a small demonstration in support of political prisoners and took her and others to the Okrestina detention center, notorious for numerous cases of torture documented there.

Along with 23 other prisoners, she spent 72 hours in a six-person cell without bedding, toilet paper, soap or a heater during a freezing winter. Occasionally, prison guards would dump chlorine water into the cell, which lacked ventilation. They would also sling insults at the prisoners and slam their heads against the walls. A homeless woman was placed in the cell to “psychologically pressure” the others.

“The guards were shocked to learn how kindly we treated the woman, how we offered her extra food—they thought we would devour her,” Katia said with a chuckle.

Eventually a judge sentenced Katia to her 15 days in jail, and she was relocated to a new facility. She described conditions there as “less brutal,” but guards would still wake prisoners at 6 a.m. with the Belarusian hymn and blast the official state news radio station all day. The lights in the cell would never go off.

‘They decided to take revenge on election observers’

Daria Smardak, a 24-year-old IT specialist who now lives in Vilnius, witnessed the fabrications of the 2020 elections firsthand as an observer. She was assigned to monitor elections at her childhood school, which hosted a polling station.

After security guards blocked her from the premises, she became resentful toward her former principal and teachers who were “playing along with this charade.” Although the polling station registered 400 votes, Daria’s group of observers counted only roughly 100 voters entering the premises.

Throughout the next few weeks, Daria became aware that she was on the radar of the security service, still called the KGB. Officers had visited her university, asking about her political leanings.

While the danger seemed to subside over time, she eventually faced a final red flag a year later. “I guess they decided they would finally take revenge on election observers,” she told me with a chuckle, calling over Zoom from the office of her Belarusian tech company, relocated to Vilnius.

On a December morning in 2021, a member of the activist organization Vyasna notified her that the police would likely raid her family’s apartment. Having already acquired a Polish tech specialist visa—in the wake of the protests, Poland had sought to capitalize on the mass exodus of Belarusian tech specialists—she set her sights on Lithuania. She left that night and by 4 a.m. was already crossing the border.

At 10 a.m. the following morning, she received a message from her mother saying the police had come to their apartment. “I don’t know what consequences I might have faced but they certainly would not have been good,” she said.

Fleeing through Ukraine

A year after her release from prison, Katia’s continuing activism put her in even worse peril. Just one month before Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, officers showed up at the veterinary clinic where she worked, brandishing assault rifles. She managed to escape through the back door. An activist tracking her case soon messaged her instructions for finding a shelter in a village outside Minsk.

She later discovered that the authorities had searched for her for two months, monitoring the phones of her relatives and interrogating her friends. Security cameras had captured Katia painting antigovernment graffiti, and, although she was masked, it seemed a friend had revealed her identity under interrogation. “Had they caught me, they would have certainly forced a confession [through torture],” she said, noting that she would have likely received a prison sentence of at least eight years.

Before going to the shelter, she drained the battery on the phone so the authorities could no longer track her. “We Belarusians are all cybersecurity experts,” she quipped about how a generation of politically active Belarusians has learned digital protocols to evade the authorities.

“At the time, my mind was telling me that nothing had happened, that I would be able to resume my life the next day,” she said. But the warrant for her arrest meant her life had categorically changed and that she would be forced to leave behind her family, pets, job and home for the indefinite future.

A common evacuation route for Belarusian activists before Moscow’s invasion took them first through Russia and then into Ukraine. Russia and Belarus share an open border, making it easy to cross without confronting their own border guards. From Russia, Belarusians were able to freely enter Ukraine.

The war cut off that evacuation route; Katia was one of the lucky few who managed to complete her journey just weeks earlier. After spending a day at the shelter, she boarded a Soviet-era share taxi headed for Moscow, without a phone and in a new set of clothes. From there, contacts would guide her to another bus headed for Kyiv.

She arrived in the Ukrainian capital just 17 days before Russia launched its first rockets, staying at a co-living space for exiled Belarusians. Although she worried that war was “already in the air,” she refused to believe a full-scale invasion was even possible—until it happened.

At 5 a.m. on February 24, 2022, she was awoken by the sound of rockets. She organized an evacuation bus to take the Belarusians to Poland. Initially, she thought about remaining in Ukraine to help a country in peril, but her fellow Belarusians pleaded with her to stay with them.

She described the border crossing into Poland as a hellish experience. “There were scores of families with all their belongings, abandoning their cars and walking toward the border,” she recalled. Food and water were scarce, and desperation set in. On two separate occasions, people died in scrambles trying to cross the border, limbs were broken, and pets perished in the cold.

The Belarusians finally crossed to the Polish side, where they were greeted by volunteers with food, water and blankets. But not everyone from their bus made it. “Some were taken away in ambulances; others lost their minds and went back to Kyiv,” Katia said. “It was no excursion.”

One of the Belarusians wrapped himself in the white-red-white flag of protest. But a Ukrainian volunteer quickly tore it from his back, surprising Katia, who had been convinced that anti-regime Belarusians were welcomed with open arms in Europe. “Minsk’s support of the Russian invasion had suddenly changed people’s perception of us,” she said.

Over time, however, that opinion has improved, she added, especially among the Ukrainian diasporas. In Lithuania, exiled Belarusian organizations raise funds for Ukraine, and Belarusians interact with Ukrainians in their native tongue, as the languages are mutually intelligible.

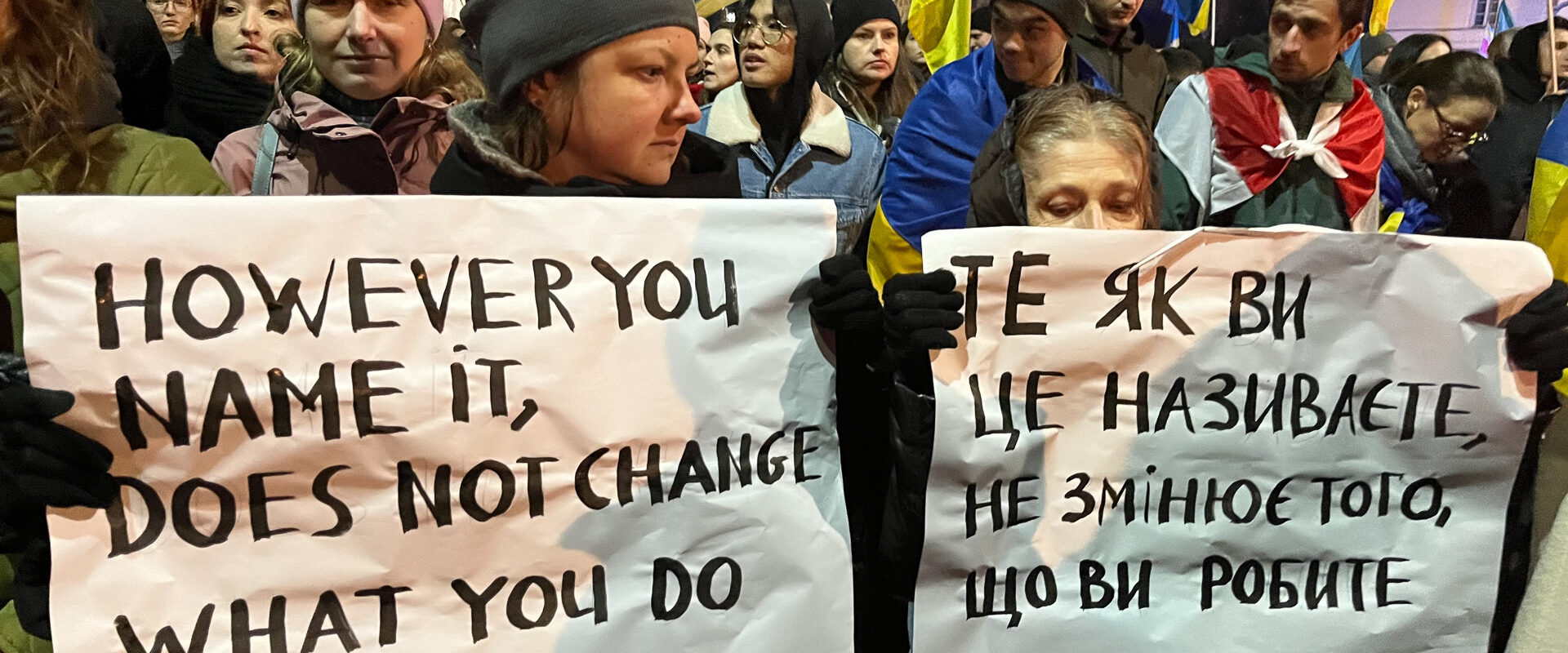

I observed the solidarity between Ukrainians and Belarusians firsthand in Warsaw. On the first anniversary of the invasion, exiled Belarusian activists were invited to speak on a stage at Ukrainian protests outside the Russian Embassy. Belarusian red-and-white flags were flown alongside the familiar Ukrainian blue and yellow.

Russian exiles—still perceived by many pro-Ukrainian voices as complicit in Putin’s aggression—would certainly not have been similarly embraced.

Exile in Georgia

The numbers 53, 27 are the latitudinal and longitudinal coordinates of Minsk. They’re also the name of Ilia’s Belarusian expat bar in Tbilisi, where Belarusians and Russians gather weekly to sip Soviet-era Belarusian Zhigulevskoye lager, listen to exiled DJs and enjoy dranniki, a traditional Belarusian potato dish like latkes.

In the backyard, Belarusian artists have painted the walls with graffiti-style homages to their estranged but still beloved Minsk. Replicas of famous Belarusian paintings adorn the wallpapered walls and the furniture evokes a rustic atmosphere.

“I wanted to create a slice of Belarus here in Tbilisi,” Ilia told me, “both to feed the nostalgia of our compatriots here and for locals to get a taste of what our culture is like.”

But few Georgians are drawn to the venue.

On one occasion, a Georgian woman snapped at Ilia and his Belarusian friends while they were hanging out in front of the bar. She called them “occupiers”—a common term flung at the thousands of Russian exiles here.

When Ilia tried to explain that they were from Belarus, she responded that Belarusians were no different from Russians.

Some 15,000 Belarusians reportedly entered Georgia after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, joining a growing number of Russian emigres attracted by the country’s visa-free policies. However, unlike in Lithuania and Poland, where locals are more attuned to their plight, Belarusians have not been as warmly welcomed by Georgians, who associate them with their government’s complicity in the war.

Effectively a Russian vassal, Lukashenka has relied on his country’s neighboring hegemon for cheap energy, loans and military support. Although the Belarusian army is not actively engaged in the conflict in Ukraine, the country has been used to store Russian weapons and ammunition, and as a shelter for the Russian private military Wagner group. During the initial stages of the conflict, Russian forces attacked Ukraine from Belarusian territory.

Marko, the musician who lost his father, was among the scores of Belarusians who arrived in Georgia after the invasion. However, his route was slightly different because he had been living in Moscow for several years.

He had begun a joint Master’s program in culturology and Eastern European studies at Moscow’s prestigious Higher School of Economics in 2021. He was supposed to spend his second year at the University of Warsaw, but the war disrupted his program along with scores of other international exchanges.

Because Marko had many friends and relatives in Ukraine, he did not want to remain in Russia and be “in any way complicit” in the invasion. In Tbilisi, he has tried to integrate with the locals despite the hostility of many Georgians. “Unfortunately, many just don’t know our full history and don’t realize that Belarus is also a victim of Russian imperialism,” he said.

To remedy that, he speaks at length with people he meets to try to enlighten them about the context. Inspired by Tbilisi’s robust electronic-music scene and coffee-shop culture—he also works as a barista—he initially wanted to make the city his home. He has even been studying the Georgian language, a task many foreigners who’ve tried admit is not easy. But recent political turmoil here and signs the Georgian government may be tilting in a pro-Russian direction have sown doubts about his prospects.

“The complete lack of stability here and dim perspectives have forced me to consider going elsewhere,” he said. “In my case, it could be particularly dangerous if the Georgian government eventually begins to collaborate with Belarus and Russia.

Although the death of his father in detention should qualify him for humanitarian visas and refugee status further west in Europe, his application in Poland was rejected on the grounds that Georgia is a “safe third country.”

But Georgia’s political reality suggests otherwise.

Prospects for the diaspora

In Lithuania—a traditional destination for Belarusian exiles—prospects are also beginning to dim as the government has become more stringent granting refugee status. Although she has a humanitarian visa, Katia was recently declined refugee status because she lacked evidence to prove a criminal case had been opened against her back home.

Approximately 61,000 Belarusians reside in the country as of this year, making them the second-largest diaspora after Ukrainians. In Vilnius, officials continue to debate whether more restrictions should be imposed on Belarusians, with critics fearing government agents may be hiding among the influx of émigrés.

After the Belarusian government enacted a law in 2023 that blocks its citizens from renewing their passports abroad, exiles are now in an even more precarious position. If forced to return, many would undoubtedly face persecution.

“I would say that 80 percent of the several-hundred Belarusians I know in Lithuania are ‘ugolovniki,’” Katia said, using Russian slang for people facing criminal charges back home.

Sviatlana Tsikhanovskaya, the de-facto leader of the Belarusian opposition in exile, continues to advocate for easing restrictions for Belarusians, emphasizing that Belarus and its people are victims rather than collaborators of the Kremlin.

Despite the uncertainty over the legal status of Belarusians in Lithuania, Katia is grateful for the country’s hospitality. As a courier, she earns more in Vilnius than she did working at a veterinary clinic back home.

She continues working with animals as a hobby, helping dogs and cats from Belarusian animal shelters find homes with Lithuanian families. “The way they treat animals here feels like heaven compared to back home,” she said. “They treat humans like animals in Belarus, so you can imagine the treatment actual animals receive.”

For any change to occur back home, all the Belarusians I spoke to agreed, Russia must be defeated on the battlefield in Ukraine. If Putin’s regime totters, the logic goes, Lukashenko’s will follow. “Our country is effectively occupied by Russia,” Marko said. “We have [Russian] military bases there. If the 2020 protests had succeeded, Russia would have invaded our country.”

Perhaps because he has been living in Georgia, far from the more unified Belarusian diasporas in Poland and Lithuania, Marko is doubtful about the political power of his compatriots abroad. “I don’t feel much unity or pride for our national identity, at least not in Georgia—it’s not like it is for the Ukrainians,” he said.

He’s also critical of Belarusian opposition members in exile, believing they should focus more on advocating for exiled citizens in perilous situations who may soon face a choice between statelessness or prison. Instead, he said, they seem too concerned with “fighting each other.”

“They’ve been speaking about issuing us alternative passports for over a year now but I see no progress on that front,” he told me.

From Lithuania, where her safety seems more assured, Katia sees things differently. “Considering the compact size of our country and the will of our people, Belarus could prove itself as a country that recovered from the crisis” if Lukashenko falls, she said. “Our diaspora has a unique vantage point in that living in Western democracies, we can see what is and isn’t effective in such systems and return to build an even stronger Belarus.”

Top photo: An exiled Belarusian protester (right, draped in the red and white flag) at a 2023 rally in support of Ukraine in Warsaw