Solo, Indonesia — How many graduates must be arrested on terrorism charges for the Indonesian government to shut down a school? Whatever tipping point you may have in mind, Ngruki’s alumni list is probably multiples of that number.

The school is among the most famous terrorist training sites in Indonesia. Since its founding in 1972, four teachers and 14 students who have called the pesantren (Muslim boarding school) home have been linked to terrorist attacks, including the 2002 Bali nightclub bombings, the 2003 Marriot hotel bombings in Jakarta and the 2009 Marriot and Ritz Carlton bombings in the nation’s capital. The International Crisis Group has dubbed Ngruki the Ivy League of recruiting for Jemaah Islamiah, an Indonesian terrorist group.

Its spiritual leader, who is thought to have links to Al Qaeda, is one of the school’s two founders. Abu Bakar Bashir spent more than a year in jail for his involvement in planning the Marriot hotel bombings, and upon his release started sending money to a military training camp in South Aceh that sought to send soldiers to Syria. That earned him a 15-year stint in a prison just south of Jakarta, where he remains today. But incarceration hasn’t kept him away from his Ngruki family—in June, he celebrated Eid ul Fitr holidays with his grandchildren and members of the school.[1]

The kyai (principal) who replaced him was quoted by a local newspaper affirming that the school will continue to teach jihad in Bashir’s absence.[2] Closely surveilled by government officials, Ngruki continues to operate in the city of Solo, Indonesia, where President Joko Widodo once served as mayor. The school’s leaders are also called to Jakarta annually for questioning. But even in the shadow of a mountain of suspicion, the institution has never been forced to shutter.

What does it take for the Indonesian authorities to deem an educational space “radical?” Once a pesantren such as Ngruki has been assigned that designation, what steps does the Religion Ministry take to deradicalize it? Are such programs of deradicalization working in Indonesia?

I managed to gain entry to Ngruki with the help of a friend. What I found was a tamed space being held up as a warning to all that might follow its example. But it is worrying that what actually constitutes “radicalism” remains undefined. Deradicalization programs are informal and unorganized, amounting to little more than surreptitious inspections and unclear edicts. Most troubling of all is that there is plenty of reason to believe that even in 2017, many Indonesian schools remain unknown to the multiple ministries that oversee education in the country. There is plenty of reason to believe that schools wishing to remain off the radar can, and that they are teaching terror.

Pondok Pesantren Ngruki

Getting an invitation to such a radical place took some doing. My friend Zacky Satya’s mother teaches at a local public school with another teacher named Agus Waluyo, who also teaches math at Ngruki. After I visited his home, Agus sent the school a text to request permission for me to visit. When it was granted, he told me to meet him there in the morning so he could give me a tour.

The next day, as Zacky a 28-year old experiential educator who hopes to send his kids to this pesantren one day drives us in the direction of the place, I discover that Ngruki is not actually the name of the school, but the neighborhood. Although both supporters and detractors now use that appellation for the educational space, according to Google Maps, our destination is pondok pesantren Al Mukmin. Al mukmin, in Arabic, means “the believers.”

As we approach, the Indonesian language on stores and street signs gives way to Arabic. As we near the pesantren itself, many signs are illegible to me, written in Arabic script.

It’s fortunate Google made me aware of the school’s official name, as that is what appears in large lettering on the building’s face. The ground floor is now rented out to a small market with an Arabic name. I am reminded of Malcolm X’s masjid number seven in Harlem, and wonder if this institution’s glory days are similarly behind it.

A security guard at the back gate asks who I am and why we have come. Zacky does the talking, telling him we are friends of Agus Waluyo, and have the kyai’s permission to visit. The guard makes a brief phone call to confirm our appointment, turns to us with a smile and instructs us to sign the guest book. I am a bit surprised to find that the guest book already has 30 or 40 full pages. “We receive a lot of guests,” the security guard tells me. [3]

A short stretch of road lies between the security post and the main office, to the left of which hang posters declaring the school’s “A” accreditation. At the end of the road stands a goateed man wearing a black peci (Muslim hat) and a grey shirt with an Arab-style collar emblazoned with the school’s insignia. Mukson (who, like many Indonesians, has only one name) smiles as he introduces himself. He is an office staff member assigned to welcome us. Like many staff members of the Al Mukmin community, he is a graduate of the school, along with his wife, who teaches preschool here. Mukson leads us into the sitting room outside the office. He tells me that although the school receives many visitors, guests like me are rare, and asks what I hope to find. I tell him I want to learn more about how the school has incorporated the national curriculum into its Islamic teaching, but I think we both know I want to see for myself whether the school is still radical or has been tamed by the state and is being kept as the government’s black sheep.

He tells me the school fully incorporates the national curriculum, and that religious learning is worked around it—students wake up for morning prayers at 3:30 a.m. and then have two hours to study their Qur’an. After evening prayers at 6 p.m., students are encouraged to recite the pages they studied in the morning. In addition to meeting the state’s expectations, Ngruki students are expected to memorize three juz (chapters of the Qur’an, of 30 total) each year they study here.

I ask Mukson about the school’s relationship with state auditors and government officials and he tells me that a good number of visitors come with smiles on their faces but suspicion in their eyes. On more than one occasion, the school’s leaders have been summoned to Jakarta and waited an entire day only to be sent home without ever even having been informed about the purpose of their trips. I sympathize with him; the government is well within its rights to behave that way, but its actions are too passive to count as a deradicalization program, and overtly distrustful.

When I finally bring up the school’s radical reputation, there is no hint of defensiveness in Mukson’s tone. He tells us that while a few graduates have gone the wrong way, most work diligently to make their communities better places, finding employment as doctors, teachers and even janitors. “A few rotten apples,” so the story goes. There were real problems here the past, but that past is now distant, this space is now open, and the people who teach and learn here don’t know what more they could do to prove it.

What do you have to hide?

Is this all a ruse? Am I being presented a censored version of the school? Mukson has politely fielded every question Zacky and I posed, but it is his word against the world’s—every friend I consulted before I visited warned me to stay away from this place. There was only one way to know whether I was seeing a dog-and-pony show: take a tour and talk to folks. Just how open is Al Mukmin?

To his credit, Mukson doesn’t hesitate to say yes when I ask if I can walk around, even after Zacky excuses himself to run some errands. Left to my own devices, I walk further back along the road that brought me to the office until I come to an inner courtyard. Standing in the heart of Ngruki, I see a masjid (house of prayer), a large dormitory with the school’s name written in tile on the roof and a group of children kicking around a ball. Most who pass me by offer greetings in Indonesian or Arabic. But I don’t engage anyone in conversation until a man dressed in a Muslim hat and tunic greets me in English.

Hartoyo, an English teacher who is also a graduate of the school, explains that Ngruki is divided by gender. Only men teach the boys, but as long as they are already married, male teachers can also teach the girls. He teaches on both campuses.

On our way to class, we first pass through the boys’ dorm. Floors of bedrooms circle a soccer field and basketball court. Peeking into one of the rooms, I see that it is subdivided by file cabinets and screens to create separate, unenclosed living spaces, each wide enough for only a floor mat and an equivalent area to place folded clothes and learning materials. Life here looks spartan. The low din of boys’ chatter dominates the dorms. As I pass groups of boys standing outside of the rooms, they smile shyly and a few greet me in Indonesian.

A group of boys whom Hartoyo says I will be teaching are standing outside the classroom on the third floor of the recently renovated academic building. Now aware that I had unintentionally volunteered to teach his class, I use the opportunity to get the boys talking before they go into student mode. They are big fans of Michael Jordan but haven’t heard of Stephen Curry. They are heavily reliant on Bahasa Indonesia to communicate with me. And they really want to take a picture together.

The boys are in their final year of high school, which means they will soon sit for a moderately difficult English test. The school also expects the boys to have memorized about half of the Qur’an by now. They direct one student to answer all of my questions, probably because he is the best English speaker in the room. He tells me he is from Solong, Papua, which is far away.

By repeating my question in Indonesian and asking for a show of hands, I learn that most of the students come from central Java. I also ask how many chapters of the Qur’an they have memorized, counting up from one so everyone can start with pride. By the time I get to five, most of their hands are down. Then I write two questions on the board: What do you want to be when you grow up, and what do you think of the United States? It initiates the oddest moment of the day. When students hesitate to answer, Hartoyo not-so-gently rephrases my question and answers it: “Are you going to be terrorists? No!” We all remain silent, and then he declares that time’s up.

Minutes later, I am hurried into a classroom where girls sit waiting. As I enter, many of them duck down immediately and rush to retrieve articles of clothing from their bags with which to cover their faces. I avert my gaze and apologize in Indonesian for startling them. Great first impression.

When I look up, I see many of the female teachers outside. They aren’t bothered by my presence, though—they are smiling at me and making recordings with their phones. I receive different results from my schtick on this side of campus. The girls don’t know my home state of Missouri, but they know the Mississippi River and that it is the second-largest in the world. Many speak a considerable amount of English and, like the boys, most indicate they grew up in villages near Ngruki.

This group is a year younger than the boys, which makes their superior English skills just that much more impressive. They also best the boys in Qur’anic studies: Every girl in the class proudly holds up her hand through 12 chapters, but some keep going. A shy girl who keeps her face covered and never speaks to me is especially impressive. She has memorized all 30 juz. That makes her a hafidza, or a woman who has committed the entire Qur’an to memory, quite an accomplishment around these parts, even if no national standardized test values it.

As our time together comes to an end, I ask what they think of the United States. “Frightening.” “Amazing.” I tell them both answers make sense to me. Before we part ways, they ask to take a group selfie. Later that week, I receive invitations from many of them on Facebook and Instagram, and see the pictures of our group posted on their pages. Kids will be kids, and those here don’t seem much different to me than kids I’ve met elsewhere in this country, except for the fact that the girls here know a bit more of the Qur’an.

Give me a sign

The difference between the boys’ and girls’ spaces says a lot about their respective educational experiences. The dorm, classroom building, and prayer space of the girls’ campus is much smaller than the boys’, although enrollment is roughly equal. The girls’ campus has no sports areas and offers less room to roam. The lack of distractions may partially explain why girls outperform boys in English and Qur’anic studies here.

One difference students may find minor caught my eye as an educator and a guest interested in deradicalization: the “third teacher,” a term often used for the walls of the space. The writing on the wall conditions the way we feel about spaces, and the hangings posted on the walls of this school have much to say about the ideological climate of the boys’ and girls’ spaces.

Two paintings from the boys’ side serve well as examples. The first read, “All people cry when they enter the world, but the world is happy to receive them. Become a person that commands respect—when you die, the world will cry, and you will be happy.” A friend tells me this is a common Islamic teaching, but coaxing boys to think about how they will be perceived when they die is not something I’ve seen in a school before. Here it hangs right outside the front door. (Tellingly, the sign was written in Indonesian and hangs right above a poster that reads “speak English or Arabic.”)

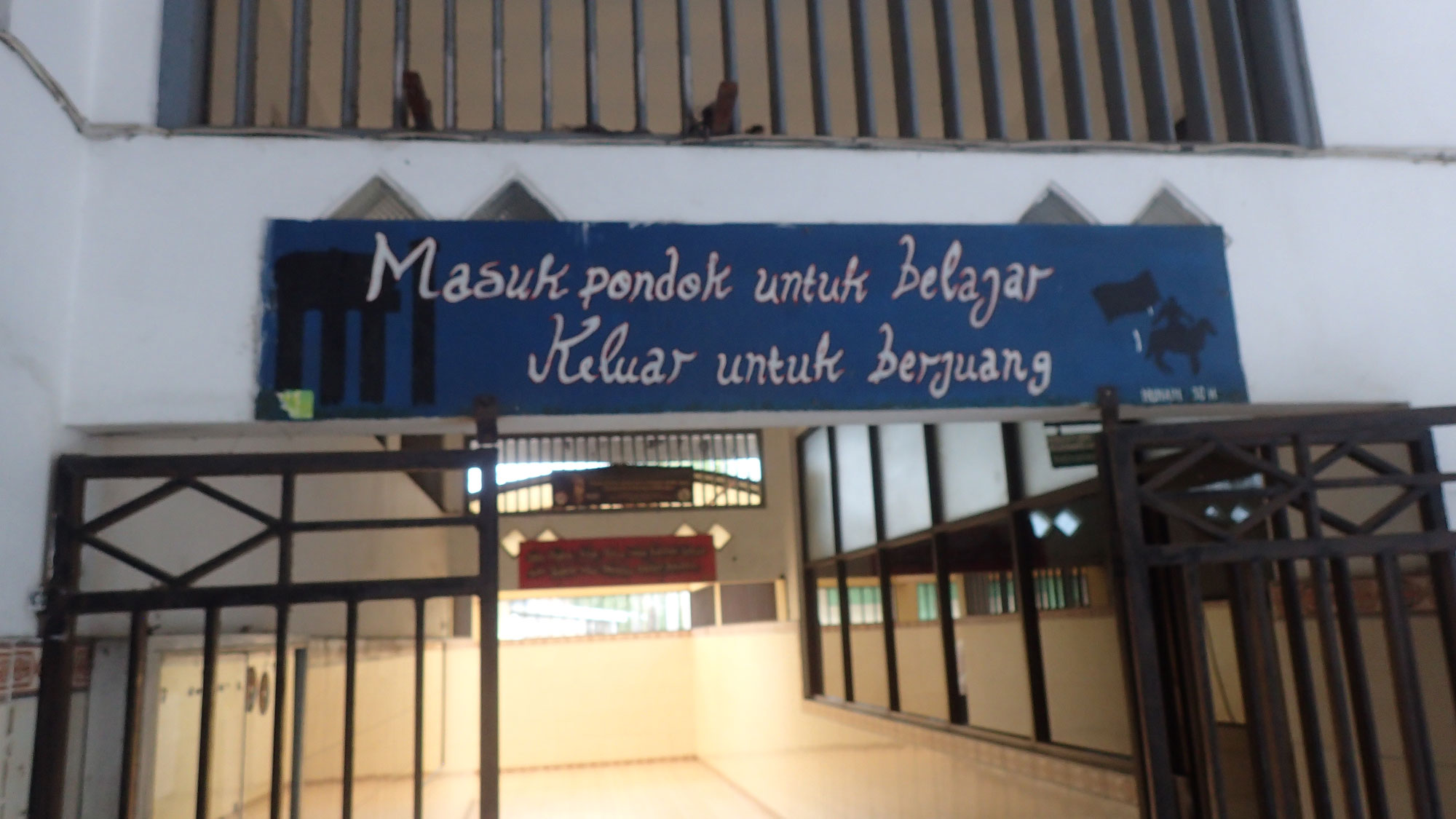

Another sign that hangs above the back door of the dorm builds on the same theme. It reads, simply, “Enter the Islamic school to learn. Leave to struggle.”

The signs mounted on the single decorated wall of the girl’s campus was a study in contrasts. Many appear to be student-made, suggesting a focus on arts education that was also reflected in the drawings posted on many of their online accounts, as I later learn.

Unlike on the boy’s side, the signs here are mostly written in English. There is a notable difference in tone between the messages boys see every days and sentiments like “Let’s learn to respect the others” and “Life is like riding a bicycle—to keep your balance, you must keep moving.” Below those, from left to right, the signs read “Blame defeats us,” “Distance yourself from sin” and hang alongside pictures of boys and girls wearing hijab and peci, “Stop pulling my leg!” along with an Indonesian translation, and examples of student work hanging in a frame shaped like Apple’s logo. The girls pass this wall every day on their way to the classroom building.

Dangerous Spaces

Is Ngruki still a radical educational space? After a single pre-announced visit, I can’t answer with certainty, but my interactions and observations suggest that the school is tame. Its reputation is more dangerous that its education, and that reputation is not enough to deter applications, which still exceed enrollment at all three levels of the school.

The guestbook also suggests the space is open to outsiders, be they parents, undercover police officers or both.[4] Even the hiring practices have been opened up because the lack of Al Mukmin graduates certified to teach science has forced the school to recruit teachers from public schools. Still, the state and society continue to uphold this school as a sort of scapegoat trophy.

That is the problem as I see it: There is literally nothing the school could do to shake the stigma of terrorism. The school directors allow all visitors, even me. They have also loudly and proudly adopted the national curriculum, even adjusting their hiring practices to ensure compliance, and attend all meetings to which they are invited, even after several rounds of cancellations on the part of state officials. Because there is no deradicalization program for them to follow or government representative to perform reviews and provide written expectations for improvement, they are left to guess what it would take to appease the state.

In saying nothing, the state is sending a mixed message. The refusal to offer a way to salvation leaves Al Mukmin open to the accusing whispers of ideologues and impugning by journalists. By allowing the school to continue to operate, the state also somehow signals the problem is now under control. Even if it is, there is no replicable process or action that could be taken in the case of other radical schools.

More worrying still is that the many ministries responsible for Indonesian education probably don’t even know about some schools that have indisputably been radicalized, even in the capital’s back yard. While I was writing this article, Reuters reported about a pesantren just fifty miles south of Jakarta, Ibnu Mas’ud, which sent eight teachers and four students to the Middle East to fight for the Islamic State group between 2013 and 2016. One of the fighters was only 11 years old. Another 18 people associated with the school have been convicted or are under arrest for militant plots or attacks in Indonesia. When that was brought to the attention of Indonesia’s director of Islamic education, Kamaruddin Amin, his only defense was that “Ibu Mas’ud never registered as a pesantren.”[5] If Indonesia has instituted a deradicalization program, that was surely its nadir.

My visit suggests that Ngruki is no longer a radical space, but also that the state’s strategy for returning the school to moderate ground had no effect whatsoever. As the example of Ngruki makes clear, the plan in place for schools with demonstrated histories of terrorism is to schedule meetings, send in undercover inspectors and demand compliance with one of the two national curricula currently utilized in Indonesia. That doesn’t work even for the schools of which the state is aware.

Even if school administration was to be bolstered to the point that all Indonesian schools were registered, there would still not be any clear guidelines about what religious teaching is acceptable and what falls afoul of societal acceptability—and I suspect that conversation will be avoided for as long as possible.

Ngruki will forever bear the scarlet T(errorism) to publicly message Indonesian citizens that radicalization in educational spaces is under control, but as Ibnu Mas’ud makes clear, that is not true.

Until Indonesia can clarify what counts as radical, it can’t begin to truly deradicalize. Unless it can put down its scapegoat trophies and seriously experiment with deradicalization campaigns, it won’t be able to begin assessing their effectiveness. Until the country can account for every child’s education, it will be impossible to know if radical schools are proliferating.

[1] http://www.panjimas.com/news/2017/06/29/ustadz-abu-bakar-baasyir-mendapat-kunjungan-keluarga-besarnya/

[2] http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-20177008

[3] All translations are my own, and are as true to the speakers’ intentions as the languages allow.

[4] http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/06/25/AR2005062500083.html

[5] http://www.reuters.com/article/us-indonesia-militants-school-insight/indonesian-school-a-launchpad-for-child-fighters-in-syrias-islamic-state-idUSKCN1BI0A7