RIYADH, Saudi Arabia — Josep is the most consistent presence in my life in Saudi Arabia. He is a short, gregarious man in his 40s with a greying goatee who works as my building’s natour, a title that encompasses most any task. The building is an old, two-story apartment complex in the central neighborhood of Sulaimaniyah in need of constant upkeep. Do I need a new gas cannister for my stove? Josep will bring it. Is the air conditioning faltering? Josep will bring in workers to repair it.

He is one of the roughly 10 million foreign workers in the kingdom, who account for about a third of the total population. He hails from Mahabalipuram, a town in southeastern India not far from the metropolis of Chennai. I once Googled it to find photos of pristine sandy beaches and extraordinary 7th-century religious monuments that have been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Why would he leave such a beautiful place for Riyadh? His answer is the same as virtually every other expat laborer’s who arrives in the kingdom: He needed a job. There were none on offer in India, and here he can earn a decent salary and send money back to his family. In 2018, the last year for which statistics are available, foreign workers sent over $36 billion out of Saudi Arabia.

Their experiences provide a window onto the many tensions in Saudi society. Their very presence is controversial: While they remain a crucial component of the economy, the government wants to cut their numbers to make way for more Saudis to enter the workforce. They often rely on informal networks made up of fellow workers from their home countries for their social lives and support of times in need, mirroring a broader fragmentation in Saudi society.

Josep has worked in Saudi Arabia for 20 years, all for the same real estate management company. Under the country’s kafala system, his visa is tied to his employer, giving him little ability to change jobs or negotiate for better pay. I wanted to learn about the changes he had seen over this time: Had conditions for workers become better or worse over that time? Had any of the recent economic or social changes affected his life?

But Josep, who was always talkative when discussing India or the functioning of our building, clammed up whenever I pursued that line of inquiry. “It’s good here,” he said during my most recent attempt. “Everything is so great.”

Recently, I thought I had made a breakthrough. Josep invited me to join him at a weekly gathering at his friend’s apartment in the neighborhood of al-Bat’ha. On Friday, the traditional day of rest in Saudi Arabia, he and his friends congregate there to relax after a long week.

Al-Bat’ha lies in the south of Riyadh, the oldest part of the capital that evokes much of the country’s history: The neighborhood is not far from the Masmak fort, whose capture by Ibn Saud in 1902 marked the beginning of the modern Saudi state, and Oud Cemetery, where all departed kings have been buried in unmarked graves.

Ironically, those once-powerful monarchs now lie in an area largely populated by foreigners. As the city has expanded north, Saudis have left the area for the glitzy, modern districts that have popped up in the desert seemingly overnight. That migration has left al-Bat’ha to poorer foreign workers. If you arrive in the morning or evening, you witness fleets of white buses shuttling the neighborhood’s population back and forth from the city center, where they work.

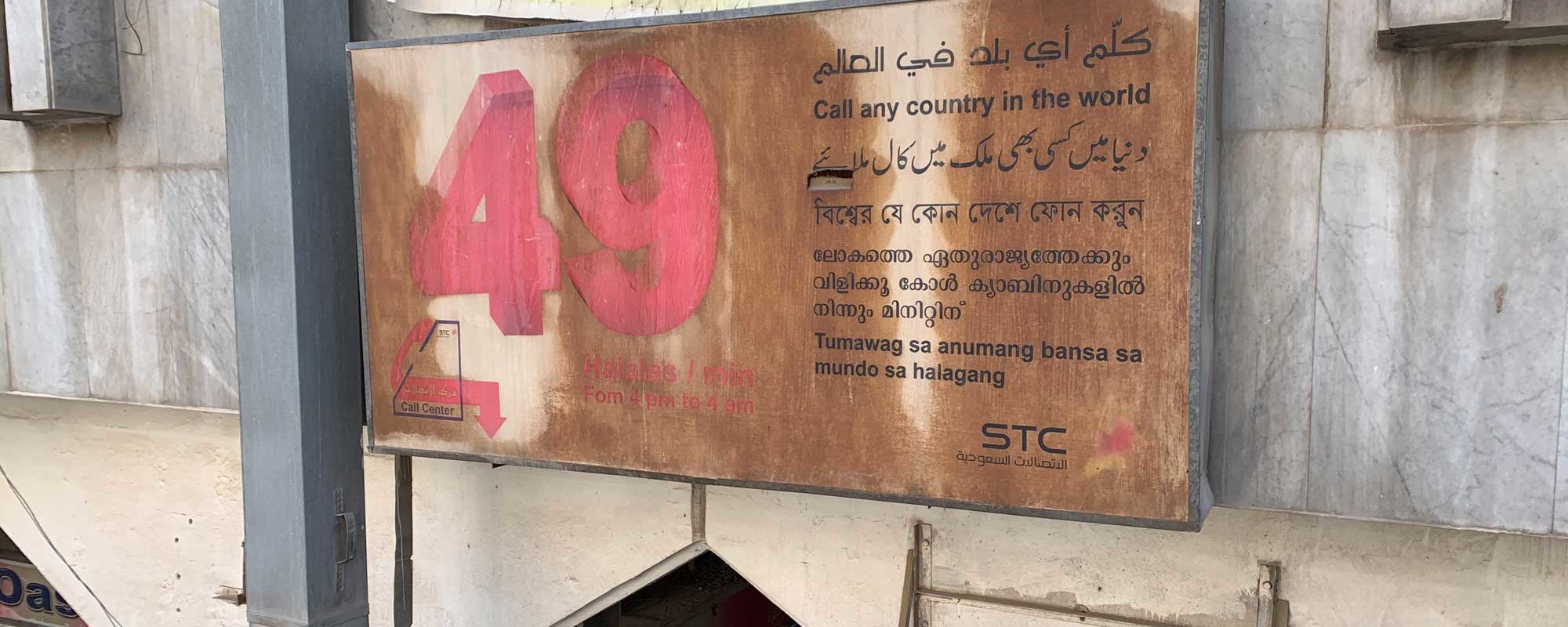

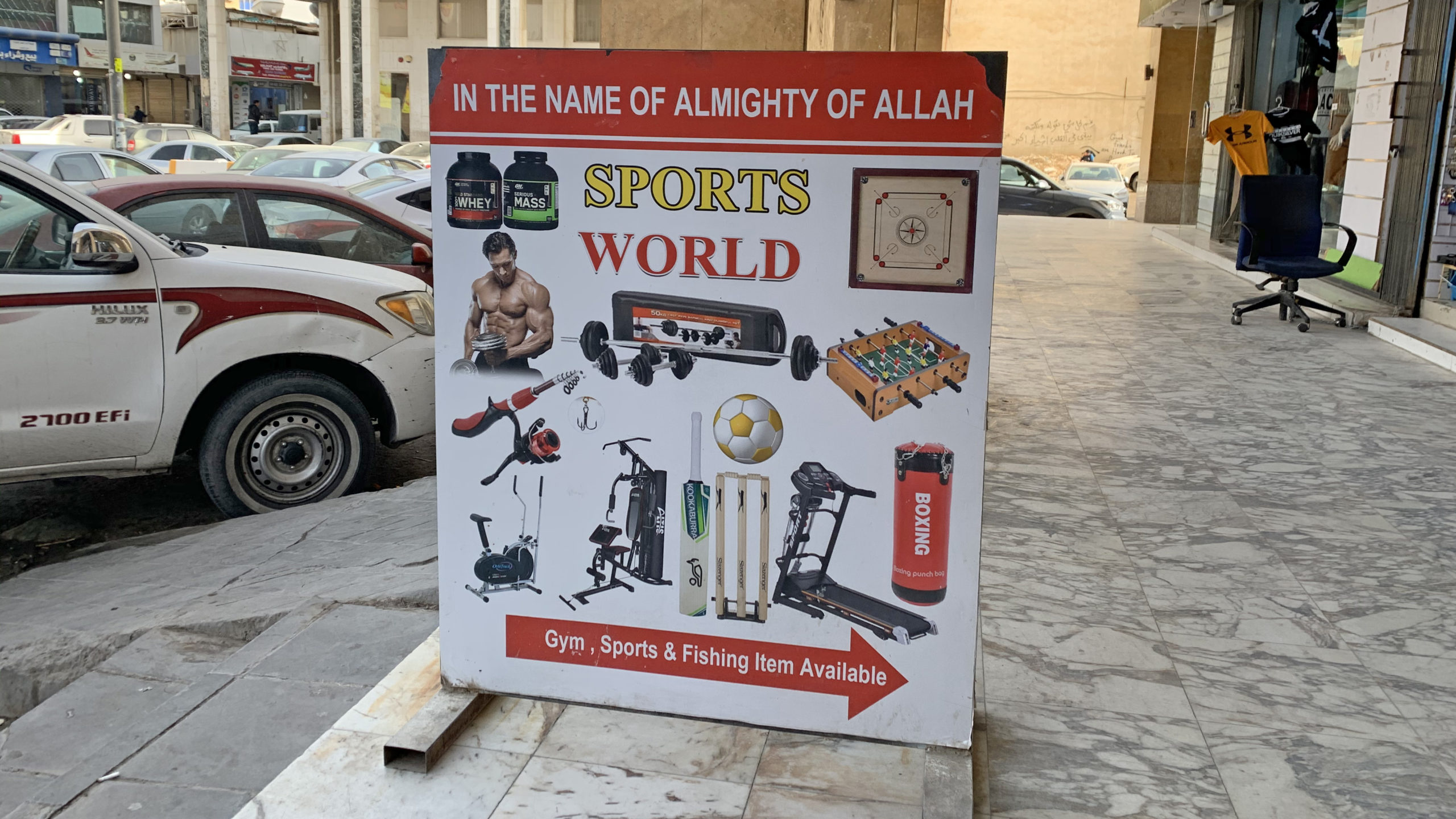

The Saudi government does not provide a breakdown by nationality of expat laborers. However, researchers estimate the three countries that have sent the most workers to Saudi Arabia to be India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Together, there are perhaps 5 million workers from these South Asian countries in the kingdom. That is certainly evident in al-Bat’ha: Hindi and Bengali scripts adorn many of the shop signs, while the Arabic name of the central commercial center has fallen into disuse. Locals refer to it simply as Seiko, after the Japanese watch company.

Josep’s friend Adil lives on the fifth floor of a gray concrete building on the neighborhood’s back streets. Climbing up to his apartment, we had to leap over parts of the stairs that had crumbled away in disrepair. The apartment itself, by contrast, was pristine—couches had been carefully positioned in a circle for the group, and tea was heating on a nearby stove.

There were six Indian men gathered in the apartment, including Josep and Adil. I had come with a long list of questions, and launched into them as we sat down. The Saudi government seemed determined to reduce its reliance on foreign workers, I pointed out—were they worried they would be forced out of the country?

‘I always had the belief that the Saudis thought we [foreign workers] were robbing them,’ my father-in-law told me. ‘They were so suspicious of us.’

Josep and his friends looked at Adil, their unofficial spokesman for the day.

“No no, it’s normal, I think we will be fine,” he said.

I did get some information out of Adil, but it was slow going. He makes 1,000 rials ($266) per month cleaning an office building in downtown Riyadh, and tries to send half his salary back home to his family in Chennai. But with the cost of living rising here, it’s sometimes less. He would retreat to generalities when I asked more pointed questions. How did he feel he was treated by Saudis, I asked—does it bother foreign workers that they work for longer hours than Saudis for less money?

“My company, they treat me fairly, everything is fine.”

The conversation would flow smoothly only when I stepped back from it. At those times, the talk would turn to family back home, shared acquaintances in Riyadh and how much money would be sent back this month.

If the situation were reversed, I’m not sure I would have spoken candidly to a nosy American who showed up to pry into my life, either. But I also think the men’s reticence went beyond an unwillingness to criticize their employers. They were not only a bit suspicious of my questions, but also weren’t quite grasping what I was trying to get at. We were speaking past each other.

Saudi society is fragmented into different sub-communities, which rarely have the opportunity to interact. When they do, it can be a struggle to find a common frame of reference. For Josep and his friends, the government had always made vaguely hostile noises and treated them like hired help. Should they be concerned by official Saudi statements when there were so many pressing concerns in their lives?

Sitting there, I remembered the journalist Andrew Hammond’s reaction on discovering a rave scene in the desert in 2009, near the end of his time in the kingdom. “After three years of living in Riyadh, I had stumbled upon a community of people I never knew existed,” he wrote in his book, The Islamic Utopia. The discovery “struck me as very typical of the atomized society Saudi Arabia is.”

After a while, I rose from the couch and said my goodbyes. Whether we live in the north or south of Riyadh, we all deserve our day of rest.

My father-in-law once was one of those foreign workers in Saudi Arabia, spending five years there helping set up its telecommunications network. Coming from civil war-wracked Lebanon in 1979, he found the kingdom at least offered the prospect of security and a steady paycheck. I hoped he might be willing to offer a more unvarnished assessment of his time there.

“I always had the belief that the Saudis thought we were robbing them,” he told me. “They were so suspicious of us.”

He was at least able to work steadily and send money back home during his time in Saudi Arabia. Not all foreign workers are so lucky. The community includes some of Saudi Arabia’s poorest residents: Some simply paid inadequately or sporadically by employers, but thousands also trapped in the kingdom with no way to earn a salary following the collapse of their employers.

For a brief moment in the 2000s, it seemed as if the state was prepared to tackle this issue head-on. Then-Crown Prince Abdullah visited the southern Riyadh neighborhood of al-Shumaisi in November 2002 in an effort to draw attention to the plight of the poorest Saudis. The neighborhood, not far from al-Bat’ha, has a similarly large population of poor foreign workers. While the government and media always focused on improving the plight of needy Saudis, some humanitarian workers held out hope that the opening would eventually create space to discuss impoverished foreign workers as well.

However, Abdullah reversed course soon after becoming king in 2005. The government shelved a national poverty reduction strategy that year, and discussion of the issue gradually disappeared from the media. The reticence continues to this day: Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 reform plan contains dozens of metrics related to every aspect of the kingdom’s economic life, but does not measure the number of foreign workers or Saudis living in poverty. A UN Special Rapporteur report released in 2017 noted that government programs are “inefficient, unsustainable, poorly coordinated and, above all, unsuccessful in providing comprehensive assistance to those most in need.”

The same report described a lack of awareness around the issue, stating “Many Saudis are convinced their country is free from poverty.”

I am watching for any signs of a renewed public conversation about how best to help the kingdom’s neediest residents, or a renewed government effort to develop statistics on the scope of the challenge. Such steps would at least ensure that foreigners like Josep bring back better stories about Saudi Arabia when they return to their home countries.