NICE — The sun was still bright at the Chateau de Crémat, perched in the hills above this Mediterranean city, when Eric Ciotti took to the podium. It was around 7 o’clock and for an hour the crowd—several hundred right-wing voters—had been mingling, waiting for the regional adviser for the center-right Republicans party to speak. Would he announce a mayoral run for next year’s municipal elections, to be held next March? Doing so would solidify his ongoing rivalry with Nice’s current mayor, Christian Estrosi, a former motorcyclist who had recently threatened to leave the Republicans.

The split between Ciotti and Estrosi helps explain why the traditional center right, once a fixture of French politics, has struggled to stay afloat in a political landscape now divided between the far-right National Rally (formerly National Front) and centrist En Marche!, the socially progressive, economically liberal party President Emmanuel Macron founded less a year before his election in 2017. The Republicans are fractured between those two currents: Ciotti’s faction, with its hardline immigration stance and focus on national identity, echoes the National Rally’s xenophobic rhetoric; Estrosi, more of a centrist, falls in line with Macron’s party. According to some rumors, he’s even considering joining forces with En Marche! candidates for the municipals.

The chasm is particularly relevant in southeastern France, a region that has become one of the National Rally’s fiefdoms. The party, which secured several mayoral seats in the 2014 municipals, swept the area—from Nice all the way to Marseille—in last May’s European Parliament elections, eclipsing En Marche! by more than 10 percentage points in a host of towns and cities. That augurs well for its chances next March, and could even boost its standing in the lead-up to the 2022 presidential vote; already in 2017, the National Rally saw unprecedented success, with party leader Marine Le Pen advancing to the second round against Macron.

Ciotti, in his 50s, is short and bald, with frameless glasses and a sleek suit. He recently made headlines for his ultimately unsuccessful attempt to ban hijabi women from accompanying their children on school fieldtrips—a proposal right-leaning politicians have advocated for years—and last year pushed through a requirement to display the French flag in every classroom across the country.

Flags, it seems, are a major preoccupation for Ciotti, and for France. For several weeks, public figures across the political spectrum had been up been up in arms over the thousands of French-Algerians who celebrated in the streets after Algeria’s recent success in the Africa Cup of Nations, often brandishing the red, green and yellow flag of the North African country, a former French colony.

“Something has been derailed in our country,” Ciotti said at the Chateau de Crémat, adding that Christian civilization “is more beautiful than any other.” “If this France is modified, if this communautarisme took its place today,” he went on, using the often-invoked word to deride multiculturalism, “it’s because we allowed into our country too many people to whom we weren’t able to send a message of assimilation and integration.” He firmly denounced the soccer demonstrations. “There is only one tricolor flag, and it belongs to France,” he boldly declared. The crowd roared.

Ciotti’s narrative on immigration and identity aligns seamlessly with the National Rally’s. It’s on the economic questions they differ: The National Rally defends a social safety net for citizens, whereas the Republicans support a leaner, less interventionist approach. And Ciotti has repeated that he’d never consider a move to the National Rally or a possible joint candidate list in next March’s elections.

Still, the group standing next to me in the crowd, all firemen, saw Ciotti as the best way to bring the National Rally’s hard line to Nice. Benjamin, 51, who’s supported the National Front for the past two decades, said he’d never consider a vote for the Republicans, but liked what Ciotti had to say. “Estrosi is just like the rest of the politicians,” he said, referring to the current Nice mayor. “He’s irresponsible with public money, he doesn’t care about security, he’s part of the elite.” And while the National Rally is fielding a candidate in Nice—Philippe Vardon, a prominent member of the “identitarian” movement—Benjamin considers Ciotti a safer bet. “If people come to your country or your apartment, and they break everything, are you just going to sit by and ignore it?” His family, who immigrated from Italy, “had no trouble integrating,” he said. “That hasn’t been true for non-Europeans. So why can’t we elect politicians who do something about it?”

Benjamin rejects the far-right label, saying he used to vote for the left. “At its core, the National Rally is a left-wing party,” he insisted, referring to its defense of the welfare state and rejection of the neoliberalism embraced by both Macron and the Republicans. That’s why he’d protested with the Yellow Vests, he told me, and believes that their anti-establishment, anti-elite demands are best addressed by the National Rally.

“Look at the places where the National Rally has managed to get elected, and look at what a good job they’re doing, how loved they are by their constituents,” he said. “If people like you—the media—weren’t so fixated on calling them a party of racists, then maybe you could see past that, and see they’re what France needs.”

Le Pen’s stronghold?

I followed Benjamin’s advice, taking a train an hour west of Nice to the idyllic coastal town of Fréjus. It’s almost comically pleasant, with its tree-lined streets and cream-colored stone buildings, a flowerbox decorating every window. There’s a lively art scene, with an entire street devoted to the studios and galleries of local painters and sculptors. The mayor’s office stands next to a cathedral and picturesque square where locals sipped aperitifs and ate ice cream, the stuff of a summer afternoon en Provence.

After three decades under a center-right mayor, Fréjus, nearing bankruptcy in 2014, elected David Racheline, a rising star in what was still called the National Front. The 26-year-old seemed to personify what was then just the debut of Marine Le Pen’s attempts to rebrand the party, distancing it from its founder, her father Jean-Marie Le Pen, who was convicted of hate speech for calling the Nazi gas chambers a “detail of history.” (Still, shortly after being elected, Racheline told the newspaper Libération that as a teenager, he had first been drawn to the National Front because Jean-Marie Le Pen “spoke perfect French.” And he “was fascinated with… Jean-Marie Le Pen,” Florian Dufait, a close friend of the mayor, told Reuters at the time).

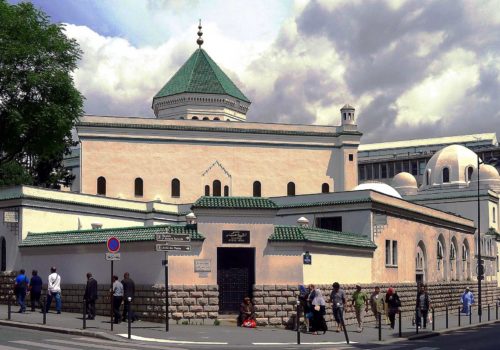

A party activist for years, Racheline pledged during his campaign to block a project to build a mosque—he was ultimately unsuccessful because the construction was already underway. Once elected, he removed the European Union flag from the Fréjus town hall; last spring, he cut funding to an organization that organized an Iftar, the break-fast Muslims partake in during Ramadan, objecting to its placement of an Islamic crescent on the event invitation. But in Fréjus’s quiet downtown, that’s not how voters see his legacy.

Anouar El-Harti, 38, owns a small grocery store at the edge of a cobblestone street. He came to France from Morocco as a child and has lived in Fréjus ever since. “With Racheline, frankly, it’s going really well,” he told me. “He’s there for the shop-owners, he listens to us, he’s done a lot for the city, sincerely, I’m very happy.” When it comes to the National Rally’s rhetoric on immigration and identity, “of course I don’t share it,” he said. But he sees where the party’s coming from and why it resonates with voters: “Sometimes it bothers me how they talk about immigrants, about Muslims. But we need to integrate, too, and if we do, everything will go fine.”

The atmosphere in Fréjus hadn’t changed since Racheline was elected in 2014, El-Harti said. I asked if he thought that some voters had initially supported the mayor not because they trusted his management skills—he was a political novice when first elected, after all—but because they supported the National Rally’s ideology. “Look, life is getting more and more expensive, people have trouble getting by,” he told me. “The average French voter thinks that foreigners are taking their jobs, so they look for a scapegoat,” he said. He doesn’t believe that’s accurate, however: “Foreigners take jobs French people don’t want, anyway. French people don’t want to work very much, they don’t want tiring work, and they want to make money. And so, what Marine Le Pen says, it’s comforting for certain people.” (France currently has tens of thousands of unfilled manufacturing jobs.)

El-Harti didn’t support Racheline in 2014; at the time, voting for the National Front was something of a taboo, he told me. “But I will in March,” he said, adding that he had voted for the party in the 2017 legislative elections and in the European parliamentary elections.

Although he wasn’t alone in his warm appraisal of Racheline’s time in office, few of the other shop-owners I encountered were willing to share their names. “As a shop-owner, I am required to be politically neutral” was the curious response I heard over and over. “I’m not a National Rally voter, but Racheline is a good mayor,” one woman, blond and in her 40s, told me from behind the cash register at her jewelry boutique. She insisted on the need to distinguish between national and local politics. I asked if she thought that, back in 2014, some Fréjus locals voted Racheline precisely because of the National Rally’s message, not despite it. “Of course,” she said. “Let’s not be naïve. If we elected a National Rally mayor, it’s because he’s from the National Rally,” even if Fréjus “doesn’t feel like a far-right town.” And, she added, “even if he’s Marine Le Pen’s right-hand-man”—he managed the campaign for her 2017 presidential run—“I’m going to vote for him in 2020 because he’s done good things for Fréjus.”

Down the street, Patrick Aboudaram, 60, was neatly placing tartes tropeziennes—sugar-studded brioches stuffed with pastry cream, a regional specialty—in the window of the bakery he runs with his children. He was short and trim, and spoke cautiously, echoing the others almost verbatim that, as a shop-owner, he couldn’t comment much on politics. “Yes, Racheline’s from the National Rally—of course, he comes from somewhere, and that’s what got him elected—but before any of that, he’s the mayor of Fréjus,” he told me. He didn’t dismiss the party’s influence on the mayor’s ideology, even if it doesn’t manifest itself in his management of the town. “But still,” he said. “It would be ridiculous to say this is a city of fascists, a city of the far right.” He added, “if anything, maybe he just reinstated an equilibrium that had been lost.” Now that meant a mayor who “values the French first.”

I wandered past the main square, which was buzzing steadily with locals drinking beers and eating salty peanuts in the late-day summer sun. One man, the owner of a sandwich shop who wanted to remain anonymous, disagreed that the National Rally’s message hadn’t left a trace on Fréjus. “You can’t call the mayor some sort of technocrat when he campaigned on shutting down a mosque,” he told me. “Tomorrow, if I open a store with a sort of ‘Muslim’ name, you better believe that it won’t go over well around here, and that’s for sure.” He grew up in Fréjus and believes that attitudes toward immigrants—both recent arrivals and the second and third generations—have hardened over the past decade. “Everyone’s moving toward the extremes,” he told me.

A few blocks away, Maryline, 48, sang Racheline’s praises when we chatted at the consignment store she runs. She doesn’t consider herself “particularly political,” but she’s a big fan of the mayor and his party. “He does a good job in the city, the streets are clean. And he’s right about immigrants,” she said. “It’s not right that we should take care of them when French people don’t have jobs or enough money.” I asked Maryline, who voted Le Pen for president in 2017 and for the National Rally in the European parliamentary elections, how the influx of migrants had affected life in Fréjus. “I haven’t seen it here,” she said. “But I watch the news and I know our country’s in crisis.”

The National Rally’s big push

The next morning, I went to La Seyne-Sur-Mer, a port city about 60 miles west of Fréjus, just outside of Toulon. Home to one of the region’s only left-leaning municipalities, it’s a prime target for the National Rally’s campaign for next March. I met Marc Vuillemot, the mayor, in his office. His bushy moustache matched his gray T-shirt, and the air-conditioning was blasting; he smoked continuously throughout our hour-long conversation.

He attributes the National Rally’s appeal in the region to “a sense of segregation” along both economic and racial lines. “There’s real poverty and the city center is run-down,” he said. La Seyne, as locals call it, is particularly polarized: It has the highest percentage of residents living under the poverty line in the entire department; for years, its households also paid the department’s highest wealth taxes (Macron eliminated the wealth tax shortly after he took office in 2017).

“When people see small businesses closing downtown, and then being replaced by kebab shops, and on top of it, they see people who don’t look like them occupying the public space, well, that generates a certain anxiety,” Vuillemot told me. “The National Front understands how to play on that, banking on the perception that the traditional parties have failed.”

Local politics present a perfect opportunity for the party to further solidify its entry into the national mainstream, he said. He pointed to Fréjus. “Racheline does a good job, so people don’t care that he defends sickening ideas,” Vuillemot explained, as long as he responds to public demands. “And slowly, people will think it’s a party like any other. That’s their whole strategy.” Traditional parties’ commitment to blocking the National Rally’s political rise at all costs, he added, has diminished considerably. Add to that a growing disillusionment with a ruling political class seen as out-of-touch and corrupt; most recently, Macron’s ecology minister, François de Rugy, was forced to resign after the investigative newspaper Médiapart revealed he was grossly misusing public funds. All of that, he said, feeds the far right’s messaging. “They’ve been trying to prove themselves, to hide the monster that’s still there, they say they’re going to clean things up. It’s a complete fantasy.”

Twenty minutes away in Toulon, I met 27-year-old Dorian Munoz, who heads the National Rally’s youth outreach in the area. He recently declared his candidacy against Vuillemot, who he says “sank the city.” “The downtown is completely abandoned, the roads are 20 years behind, and in the meantime, they’ve let in tons of migrants.” (Vuillemot says he created a center for 40 recent arrivals, all unaccompanied minors). La Seyne residents, Munoz told me, lament “rising crime and insecurity.”

He’s optimistic about his chances in La Seyne, and about the National Rally’s ability to solidify its grasp in the region. “We’re on the ground every day, every weekend, whether there are elections or not,” he said proudly. “That’s our political culture, our way of seeing politics—to establish ourselves locally.” He contrasted that to other parties that “only show up when there’s a vote to win.”

The majority of French voters are tired of the left-right dichotomy, Munoz told me, and he is too. “We’re neither left nor right,” he said, unintentionally echoing the slogan of Macron’s own presidency. “For us, there are globalists and nationalists—the people on the side of the country they’re elected to represent.” He chalks up the far-right label, and the narrative that Marine Le Pen has thought to “de-demonize” the party, to a smear campaign by political opponents. “We’re a party that evolves with the times,” he said: the National Rally no longer supports the death penalty, for example, or contests gay marriage. On Europe, too, they’ve changed, mirroring other far-right parties across the continent that no longer seek to exit the European Union, but change it from within instead. That’s become more compelling since the parliamentary elections, he said. “Now, we’re surrounded by allies.”

They’ve also developed positions on issues unrelated to immigration and security, notably including “localism,” the National Rally’s new environmental talking point. “How is it possible that it’s cheaper to buy fruits and vegetables that travel around the world to get here, and our local producers can’t make ends meet?” He believes positions like those will help attract voters fed up with other parties.

“People talk about de-demonization, but for me, we were never demons,” he laughed. His parents, second-generation Spanish immigrants, always voted National Front. “I haven’t encountered any Nazis, any of what they say about us in school.” Jean-Marie Le Pen’s founding work was “laudable,” he added. “He’s the one who inspired this desire for patriotism, this love of France, of the nation.”

I asked Munoz if he thought local successes would translate into national gains, mentioning that some Fréjus voters I encountered supported Racheline but not the National Rally. “That’s now,” he said. “But in 2014, why’d they vote Racheline? Because he was National Front.” In 2020, “people will hear about what a good job we’ve done in Fréjus by word of mouth,” he added, confident about the National Rally’s chances of maintaining its momentum moving forward. The municipal elections “are the queen of all elections,” he said. “They affect the most people’s lives. They show voters who we really are.”