BERLIN — “My Humanity Should Not Be Up For Debate,” read the sign Vanessa H. brought to the Black Lives Matter protest in Berlin’s Alexanderplatz one Sunday afternoon earlier this month. The 24-year-old Black woman, a lifelong Berliner, was one of at least 15,000 people who came that day to show solidarity with the movement in the United States.

Two days later, she picked up her son from kindergarten and stopped by a Rossmann drugstore to buy a few basic items. When she tried to pay with her debit card, the cashier asked her to sign. Apparently not believing someone with dark skin could have a typically German last name like hers, she asked for Vanessa’s ID, suggesting she was not who she claimed to be.

“The woman didn’t believe this card could belong to a Black woman like me because my name sounds German,” Vanessa said in a Facebook video recounting the incident that has since received significant attention in local media. At the time, she called the police. But rather than supporting her, one officer suggested the incident may have been the result of a misunderstanding and that the cashier simply hadn’t understood the woman’s German. Giving a false police statement could result in jail time, he warned Vanessa.

Her story is far from an isolated event in Germany. As George Floyd’s murder in the United States reverberates abroad, the protests and ensuing debates about America’s deeply ingrained racism have reignited similar discussions about racism and discrimination here.

They come at a crucial time. Racist discrimination is on the rise, according to a new report from the Federal Anti-Discrimination Agency: From 2018 to 2019, recorded cases increased by 10 percent; from 2017 to 2018, they had already increased 20 percent. And many feel the harsh anti-immigration rhetoric of the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party contributes to increased hostility toward non-white Germans and immigrants. Although many people of color are heartened to see more discussion about it and hope this moment can lead to real change, they’re also asking: What took so long?

“Of course I’m happy that there is now this conversation in Germany too because of what’s happening in the US,” Mohamed Amjahid, a German-Moroccan author and journalist who has written a book about his experiences with racism and discrimination, told me. “But at the same time, I’m mad because this is nothing new, and this is nothing we didn’t talk about before.”

The arrival of more than a million refugees in 2015 and 2016 is often billed as the source of Germany’s current issues with racism and anti-foreigner sentiment, but the reality is that Germany has a long history of immigration (even if it has only more recently begun to acknowledge that fact). In the 1950s and 1960s, millions of Gastarbeiter, or guest workers, came to West Germany, primarily from Turkey, Morocco, Tunisia, Italy, Spain, Portugal and the former Yugoslavia. Those workers played a crucial role in rebuilding the country after the destruction of World War II, contributing to the so-called German “economic miracle.” The former East Germany also brought in contract workers from countries including Vietnam, Mozambique and Algeria. Although many of those workers eventually returned to their home countries, a large number stayed. In 2018, one in four people living in Germany had a “migration background,” meaning either they or at least one of their parents were not born here.

Nevertheless, many in Germany still have a very restrictive—and inherently white—understanding of who is truly considered “German.” Just living here long-term or even being born here isn’t enough: German citizenship was long based primarily on blood ties rather than country of birth, and it wasn’t until the year 2000 that an updated immigration law shifted the balance toward recognizing birth country as the key factor. It spoke volumes that when President Christian Wulff finally acknowledged Germany to be a “country of immigration” in 2010, it was (and in certain circles remains) a contentious thing to say.

“When people talk here about race, they talk about Black people and Germans—and that is highly problematic because they’re separating Black people obviously from Germans, as well as they do with Turks, as well as with everyone who’s not white,” David Warmbold, a Black German-American who grew up in the western German city of Hannover, told me over coffee on a recent stormy Saturday afternoon. “They use the term ‘German’ specifically to mean white… having to be white to be German, it’s still based on this Nazi theory of blood and soil.”

The inability to recognize that “German” encompasses so much more than the age-old stereotype, even among those who are otherwise liberal-minded, “is really mind-boggling,” Warmbold added, “because you always feel like a guest in your own country.”

Everyday racism in Germany, and the basic assumptions people make about Germanness, often begin with a single, seemingly harmless question: “Where are you from?” That could be considered a basic and innocuous component of small talk, especially in a place like Berlin, an international city full of people from other cities and countries. But when the person being asked isn’t white, it’s often followed up by a second one: “But where are you from originally?”

“Of course, as the person affected you know what’s behind it,” said Tahir Della, spokesman for the Initiative Black People in Germany. “They’re not really interested in whether you’re from Munich, Hamburg or Frankfurt—they want to know how someone could be Black and not obviously come from somewhere else.”

Every one of the people I spoke to for this article had experienced this not once but frequently—sometimes multiple times per day. Having one’s identity questioned repeatedly is demoralizing and emotionally exhausting, they said.

They got involved and built up careers. Their children study and are successful. But the first question is always, ‘Where are you really from?’

Even Chancellor Angela Merkel addressed the issue back in February, in the aftermath of the Hanau attack. “They raise their children here, they do this and that, they speak German,” she said. “They got involved and built up careers. Their children study and are successful. But the first question is always, ‘Where are you really from?’”

For Audrey Picardo-Kirschner, a Black woman from the French island of La Réunion who’s lived in Berlin for the last decade, the question represents a basic lack of understanding that European countries like Germany or her native France are more multiethnic than most people are willing to admit. They can’t simply accept that she’s French, she told me, “I have to be French from [somewhere]. I don’t understand, actually, because in France there is a big story of immigration and everything. And ‘French’ is not just white.”

* * *

The prevailing attitude about German identity leaves out—and makes life harder for—the millions of German citizens and immigrants who don’t fit the blond-haired, blue-eyed stereotypes of a white German person. Some of their experiences are small and seemingly benign: The question about where you’re really from or a comment about how good your German is. But more significant experiences are all too frequent. Applicants with foreign-sounding names are less likely to receive a job interview or get an apartment. People of color are more likely to be turned away from a club for vague reasons of “not fitting the aesthetic” or, like Vanessa, subject to suspicion in regular daily interactions such as shopping in a drugstore. Some experiences can be traumatizing or even deadly: Being verbally or physically harassed—or, as happened in Hanau in February, even being killed—solely because of the color of your skin.

Speaking with people from various communities and backgrounds for this story, I heard about countless such experiences—many of which were never reported to the authorities but had deep impacts on those targeted. Warmbold told me, for example, that he no longer rides the regional trains near Germany because of an encounter he and a group of friends, all Black, once had with inebriated supporters of a local soccer team; sensing a potential for conflict, they went through all the train cars until they finally found a group of fans from a more liberal-minded team to sit by. “When you have to know what kind of worldview different soccer teams have without even caring whatsoever for soccer, that says something about how you need to move in a white society,” he said.

Two middle-aged men at a restaurant in the central city of Erfurt once asked an Asian-American friend whose family has roots in China and Taiwan, Gabriella Linardi, where she’s from—then casually told her they had been discussing the shape of her skull and believed it indicated she was from South Korea. “I know back in the days the Nazis determined someone’s race by their skull shape… but this was 2018,” she said.

Ramon Luz, a Black Brazilian documentary filmmaker who moved to Germany in 2017 for a fellowship, told me he was visiting the Buchenwald concentration camp near the eastern German city of Weimar when one student in a school group began screaming and laughing at him. Others joined in, creating a chorus of laughter incomprehensibly directed at him. When he told a white colleague about the incident, “he was shocked, while I wasn’t,” Luz said. “I was just sad.”

All of these experiences are exhausting and disheartening and contribute to a sense of being constantly under suspicion—or the feeling you can never truly belong here. As a white foreigner living in Germany, especially one with a German surname like mine, they are problems I’ve never had to face.

Picardo-Kirschner, put it this way: “It’s all these tiny ignorant questions, but coming in numbers every day—it hurts.”

* * *

Like in the United States when another young Black person is killed by police, discussions about racism in Germany go through predictable cycles: Something happens that underscores the challenges of everyday and structural racism, headlines focus on the incident, panels on network television discuss the issue—and then eventually it fades from the public’s consciousness again.

The most shocking such case was over the uncovering in 2011 of the National Socialist Underground, a neo-Nazi terrorist group that had committed a years-long series of murders primarily targeting people of Turkish background. An initial unwillingness to explore right-wing extremists as potential suspects—the domestic intelligence service assumed the murders were being committed by others in the Turkish community, and the media dubbed them the “kebab murders”—fueled a lack of faith among people of color that the authorities were ready to take racism and extremism seriously.

Even in my three years here, I’ve seen several such cycles come and go. In the summer of 2018, the football star Mesut Özil quit the German national team over what he described as consistently racist treatment from teammates and staff. Özil, who was born and grew up in the western German city of Gelsenkirchen, has Turkish roots; when he posed for a photo with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, he faced a firestorm of criticism and charges that he was disloyal to Germany. In a letter explaining his decision to step down, Özil outlined the big and small ways in which he felt discriminated against, by coaches and teammates and by German soccer fans. “I am German when we win, but I am an immigrant when we lose,” he wrote.

And earlier this year, when a white man gunned down nine people in two shisha bars in the city of Hanau, nearly all of whom were immigrants or had immigrant backgrounds, debates about how harmful far-right rhetoric affects attitudes toward people of color in Germany raged yet again. The newspaper Die Zeit ran a major piece on racism, asking 142 people of color (including some quoted in this story) to share their experiences. But then the pandemic came along, quickly erasing every other topic—including Hanau—from the headlines.

Part of the problem, many I spoke to said, is that white Germans often equate racism solely with neo-Nazis and far-right extremists; some aren’t willing to acknowledge that racism comes in many forms, and that they, too, could be contributing to the problem. In other words, people of color being killed by an extremist gets attention but all of the basic prejudices and assumptions that lead to racist violence are often ignored or denied.

Christa Joo Hyun D’Angelo, an Asian-American artist who’s lived in Berlin for a decade, told me that of all the places she’s called home, Germany is “probably one of the worst” when it comes to racism. It’s difficult to have conversations about representation without being accused of being overly sensitive, she says, particularly within the cultural scene—which largely views itself as progressive and colorblind. Many colleagues and others she’s encountered in Berlin’s arts scene aren’t ready “to have uncomfortable conversations and be willing to admit that you yourself could be a racist,” she said, “And that means not just being a right-wing Nazi but also someone working in culture.”

* * *

There have been some tangible steps forward in recent weeks: In Berlin, lawmakers passed a groundbreaking anti-discrimination law banning public authorities from discriminating based on race, gender or sex and giving residents the ability to file complaints for discriminatory incidents. Minority groups lauded the new law, the first of its kind in Germany, as a significant step forward in combating racism.

The new measure remains controversial, however, and immediately came under fire from politicians who said it would lead to a slew of lawsuits, or believe Germany doesn’t have a problem with structural racism. Other states’ police forces said they might be unwilling to send reinforcements to Berlin in the future for fear their officers could be sued. Interior Minister Horst Seehofer, from the Bavarian center-right Christian Social Union, said it put all police officers under “general suspicion.”

The recent protests have helped draw more attention to other ways Germany could begin combating racism. Because of the country’s Nazi past, the government does not collect data on race or ethnicity for its census. That will change this summer with the first-ever Afrozensus, a broad survey of Black people in Germany and their experiences with discrimination. Estimates put the number of people of African descent in Germany at 1 million, but people of color say the lack of more precise data hinders the country’s ability to combat structural racism.

Another campaign currently underway calls for the removal of the word “race” from Germany’s constitution, arguing it inherently contributes to division and exclusion. And many of those I spoke with said Germans have a blind spot about their country’s colonial history, which helps contribute to ignorance about racism. Della, the spokesman for the Initiative Black People in Germany, is among those who advocate for this colonial past to be taught in school curricula along with the history of the Nazi period; reforming German education would go a long way toward helping new generations understand the ways racism affects German society, he says.

In response to Vanessa H.’s case and others who have come forward with similar experiences, the drugstore company Rossmann announced it would better educate employees about racism and stop asking customers for ID in its stores. And although Seehofer defended the police in response to Berlin’s new law, the German government announced it will investigate latent racist sentiments among the police force.

Those I spoke with felt a cautious sense of optimism that the current protests might resonate more deeply than previous debates about race—or at the very least, help convince skeptics there really is a problem.

“Let’s see how long it will be still a discussion, let’s see how much it will change,” Warmbold said. “Noticing that there is a problem is the best way to find a solution to it… I hope this whole situation leads us to a point where we start to see that [racism] is way more complex than it appears to be.”

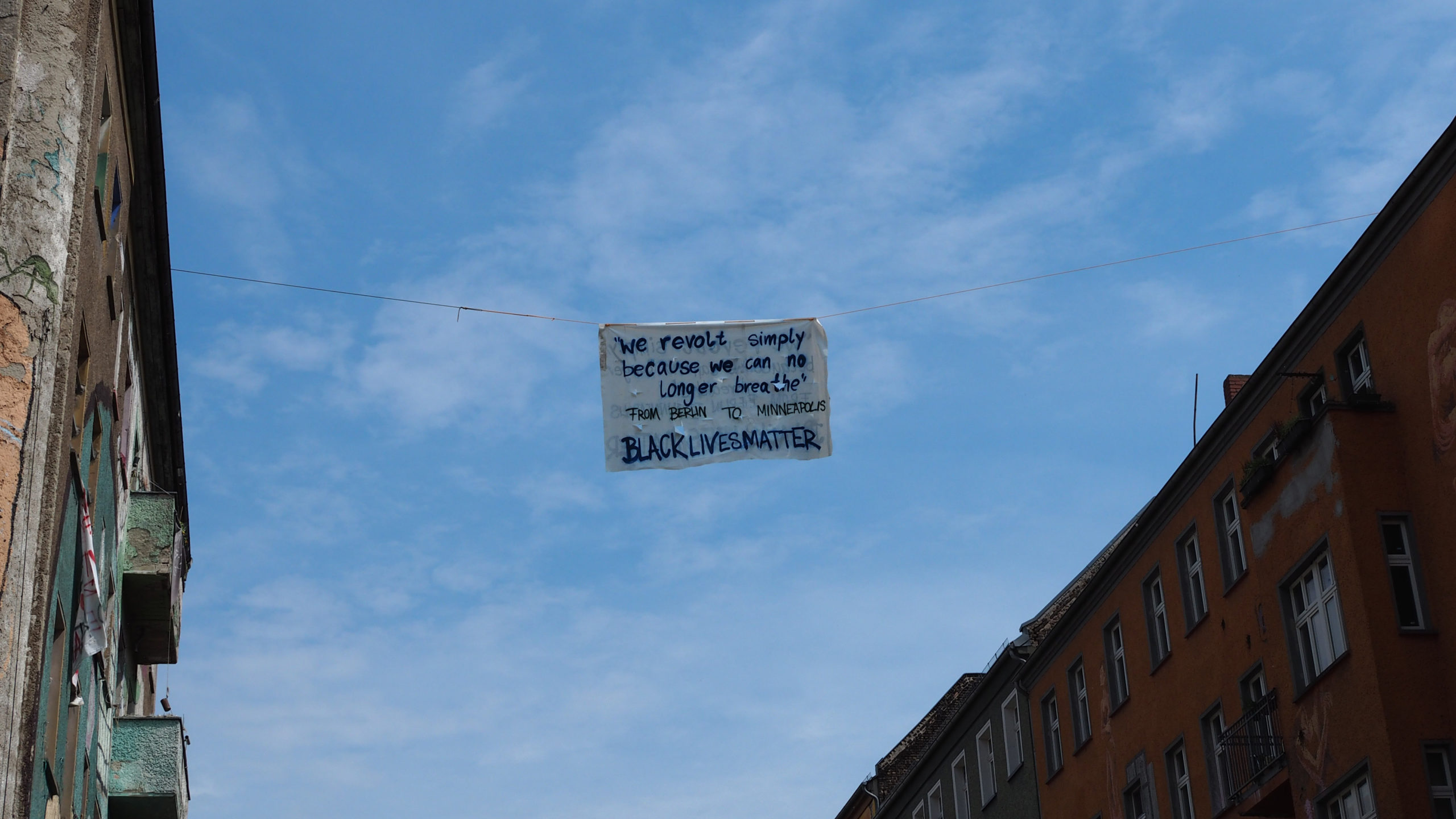

Top photo: Black Lives Matter protests drew thousands in Berlin in June 2020 (Lucas Werkmeister, Wikimedia Commons)