ORMENIO, Greece — White bearded goats with bells around their necks climbed down from tree trunks and tinkled into the forest as Páter Triantafyllos Strakos and I drove up a leaf-strewn mountain road in his blue pickup truck. With smiling eyes and a long white beard, he told me he was born in Germany in 1968 and worked as a shepherd before becoming a priest. He was taking me to see the ruins of Agios Athanasios, a church on the Greek-Bulgarian border in Greece’s northernmost region of Trigono, a triangle created by the Evros River to the north, the Arda River to the south and Bulgaria to the west.

It was November 2021, and most of the trees were brown or bare, having already shed their leaves. The priest wore a black knit cap and kept the heat on high. When we turned onto a dirt road with two parallel tracks leading through the leaves, he got out of the car to engage his four-wheel drive. Prayer beads hung from the rearview mirror, bouncing as we began rumbling over muddy ruts filled with water.

White pyramidal markers appeared in the forest along the driver’s side, denoting the border between Greece and Bulgaria. At one point, two border guards seemed to come out of the trees as we passed; at another, a green Bulgarian jeep stood in silent sentry. “You can’t take photos here,” the priest warned.

A tense thrill bloomed in my chest. This wasn’t an official checkpoint like the Ormenio-Haskovo crossing some 20 kilometers away but a symbolic line through the wild forest, enforced by officers with guns. Marked only by white pyramids, the border here seemed less stable, almost daring you to cross. How many resistance fighters hid in these woods during Greece’s Civil War from 1946 to 1949? How many Bulgarians attempted to flee through this forest to Greece during the Cold War? And how many migrants are still trying to cross this invisible line?

We reached a clearing in the woods dominated by the crumbling church of Agios Athanasios. The building, which dates back to before 1880, belonged to a settlement called Yialia (Yailajik during Ottoman rule), one of the oldest in the region. Its Greek-speaking inhabitants were herders and farmers forced to leave their homes after the 1919 Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine established the current border between Greece and Bulgaria.

It was unsettling to learn how quickly a village could be killed. The border separated farmers from their fields, cutting them off from their livelihoods. In that decade, Yialia’s population dropped from 346 to 44 as residents moved further within Greek territory, resettling in the villages of Elaia, Spilaio, Lepti and Sterna. The last family left in 1937, and the 1940 census considered Yialia officially abandoned.

The large church was little more than the remains of four stone walls, its arched windows supported by planks of wood. In 2018, the diocese of Didymoteicho, Orestiada and Soufli built a shelter over the ruins and performed restoration work with the help of the army and local parishioners. They had chopped away a tree that threatened one of the walls, but it continued to grow, its branches spreading like a network of veins inside one corner, an explosion of green leaves pushing out between wall and roof. “See how strong nature is?” the priest said.

The overgrown village illustrated the human cost of carving up the historical region of Thrace into present-day Greece, Bulgaria and Turkey. The desolate foundations covered in leafy tendrils also seemed like a harbinger of Trigono’s fate if steps are not taken to address the region’s shrinking population. The village of Ormenio, Greece’s northernmost point, had 967 permanent residents in 1991. Today, some 320 remain, most over 70 years old.

The situation in Ormenio is indicative of a larger demographic problem: Greece’s population has dropped 3.5 percent since 2011, exacerbated by emigration and decreasing birth rates during the decade-long financial crisis. Indeed, 32.4 percent of Greeks surveyed by the think-tank Dianeosis this past spring believed the population decline is the greatest threat to the country’s future. Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis created a national council in June to reverse the trend, which he described as a “ticking time bomb” posing “immediate and significant” danger to the country’s ability to grow and produce wealth.

Last year, a cross-party parliamentary committee drafted a comprehensive plan for the development of Thrace. For the 17 remaining villages of Trigono, which suffer from frequent power outages, floods, poor transportation infrastructure and a general sense of neglect, strengthening connections with Bulgaria and Turkey could help to revitalize the region.

Tea with Ormenio’s grandmothers

After visiting Agios Athanasios in Yialia, Páter Triantafyllos took me to Ormenio to have tea with three village grandmothers: Xanthoula Mpoyiatzoglou-Dimitriadou, Koula Dautzidou and Lela Voulkou. All in their 70s, the three lively, funny women told me about the village’s tumultuous history and showed me old photographs and traditional costumes while Ms. Xanthoula, as she is addressed, brought out an endless supply of treats: hand-picked chamomile tea with honey, walnut pie with raisins, homemade sour cherry liqueur and rose loukoum.

Ormenio stands on the bank of the Evros River, six kilometers south of the Bulgarian town of Svilengrad. Known as Chernomen during the Byzantine period and Chirmen during the Ottoman period, it was the site of the 1371 Battle of the Maritsa River, a decisive and bloody Ottoman victory that enabled expansion into southern Serbia and Macedonia.

Following an agreement in the 1919 Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine for Greece and Bulgaria to voluntarily exchange minority populations, Greek refugees from northern Thrace settled in the village. Most came from Kozuldzia and Urumkioy, the present-day villages of Oreshets and Efrem in Bulgaria. Ms. Koula’s father came to Greece in 1926 when he was a year old. His sister, Ms. Lela’s mother, was three years old.

By the end of the decade, a climate of intimidation forced the remaining Greek families to follow. In total, some 46,000 Greeks emigrated to Greece and twice as many Bulgarians left the country. During the 1930s, the border hardened and the Greek military erected a dense network of guard posts from Ormenio down to the village of Milia on the Arda River.

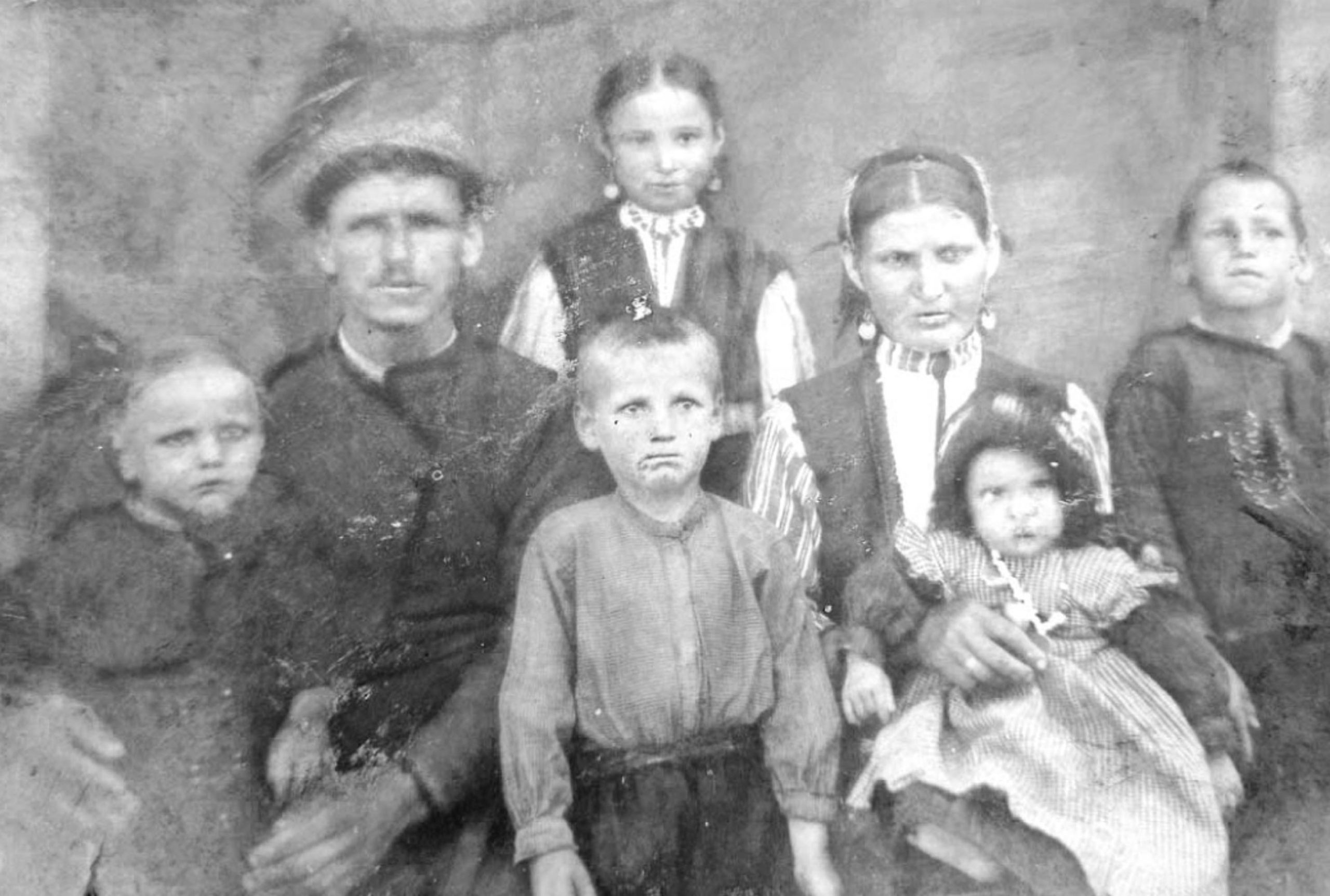

Dimitrios Strakos and his family, Greek refugees from Urumkioy, present-day Efrem, Bulgaria, in the 1930s. Dimitrios was the brother of Chrysoula and Páter Triantafyllos’s great-grandfather (Chrysoula Ioannidou)

In the decades that followed, constant conflict stunted the region’s development. During World War II, Bulgaria occupied Ormenio from 1941 to 1944. Two years later, the Greek Civil War broke out between the National Army and guerilla forces of the leftist, largely communist National Liberation Front (EAM), resulting in the deaths of many young men.

Ms. Lela’s father Panagiotis, then a 26-year-old soldier in the Greek Army, was killed three days before the civil war ended in 1949. “I was three years old then and didn’t know him at all,” she said, showing me a sepia photo of a handsome young man with a triangular mustache standing tall and solemn in his military uniform. “This photo was taken six days before he died.” The Greek letter pi for Panagiotis or patéras, father, was inscribed in light blue ink above his head. He was buried in an unmarked grave near the town of Kastoria in northern Greece.

Families in Ormenio faced great poverty, so in the late 1950s, many began leaving the village to work abroad in Germany, the first of three waves of migration. Leaving their fields, animals and children in the care of the elderly, a majority of immigrants worked in a paper factory in the village of Gemmrigheim, near Stuttgart.

Ms. Koula’s father migrated to Gemmrigheim in 1963 and returned after two-and-a-half years. “He didn’t like Germany,” she said. “He was a hunter. He wanted to stay on his farm and be his own boss. But my mother said, ‘Everyone’s going to Germany to work and make money (to build a house or buy a tractor) and have a better life.’”

Ms. Koula moved to Gemmrigheim with her parents in 1965 and married a Greek there. Her parents returned home for good in 1968, and she sent her 14-month-old daughter to live with them while she continued working at the factory. She resettled in Ormenio in 1975 after separating from her husband. Now her daughter and grandchildren live in Munich.

Subsequent waves of migration in the 1980s and during the financial crisis in the 2010s further reduced the population. Today, three times as many villagers live in Germany than in Ormenio. “One by one, the houses in the village are falling into disrepair, the village is emptying, and we’re left all on our own,” Ms. Xanthoula said. “If you walk around our neighborhood, you’ll find two houses open for every three or four closed,” Ms. Koula added. “In some neighborhoods, the homes are all closed.” They could count the village families with small children on one hand.

How to revive northern Evros?

I met Chrysoula Ioannidou, Páter Triantafyllos’s older sister, during my first month living in Evros, the regional unit of which Trigono is part. I had traveled to Ormenio’s sister village of Ptelea with Angela Giannakidou, president of the Ethnological Museum of Thrace, to catalog items from the folklore museum there and discuss how to bring more tourists to Trigono.

Chrysoula, an eloquent and engaging woman with short, white hair, lit up when she heard I wanted to write about the region. Her parents had worked in Germany, and as Ormenio’s president from 1995 to 1998, she had tried to deepen relations with Gemmrigheim. Now she acts as village historian, recording stories from older generations. She’s generous with her knowledge of Ormenio’s history and traditions, and when I came to Trigono on my own, she arranged for her brother to show me around.

The question of how to revive northern Evros is a difficult one. Chrysoula, who saw Ormenio’s primary school close during her presidency, is not at all optimistic that the village’s future will change for the better. “I expect the population to shrink even more, and I think the emigrants who don’t return from abroad will sell their fields, or some will become landowners whose fields are cultivated by others,” she said. “The region is slowly fading, unfortunately. In 2025, one hundred years after our ancestors settled in the village, we will be perhaps a hundred people in a village that has come full circle.”

Even Ms. Angela, who advocates tirelessly for Thrace, has few illusions about the impact of her work. “I’m not naïve,” she told me. “I don’t think I’ll be able to fill the villages. I’m simply trying to support what remains. Maybe that will create some life.”

Recent geopolitical developments have created a case for the region’s renewal. As a result of Russia’s war in Ukraine, new transportation and energy infrastructure and growing pressure from Turkey, the Greek government has turned its attention back to Thrace. In April, Ms. Angela brought Greek President Katerina Sakellaropoulou to Ptelea, citing its symbolic significance as home to refugees from northern Thrace who often feel forgotten, the last stop on the railroad and a treasury of traditional artifacts, especially the craft of weaving. Women carried the skill across the border from Kozuldzia and Urumkioy, although few practice it today.

Ms. Angela attributes the decline of the Trigono villages to the artificial division of historical Thrace a hundred years ago, which severed them from urban areas like Haskovo in Bulgaria and Adrianople, present-day Edirne, in Turkey. For centuries, people, goods and money flowed freely throughout the region until the partition of Thrace and displacement of its populations. Since then, the border villages of all three countries have been held back. “The three regions have to develop together,” she told me. “We have to build back the communication network that ran through Thrace during the Ottoman period.”

Now there may be political will to do exactly that.

A strategic development plan for Thrace

Last November, the Greek Parliament’s Inter-Party Committee for the Development of Thrace created a strategic plan for revitalizing the region. “Thrace, because of its geography, has issues with migration, safety, education, infrastructure and climate change,” said George Plevris, special adviser to committee chair Dora Bakoyannis, who drafted the report. “More people were leaving this area. It needed aggressive attention.”

The report, which includes ideas and proposals from locals, is meant to guide government policy. Interconnection was an overarching theme, both in its structure and specific recommendations. “We see development nowadays as an ecosystem,” Plevris told me when we met in Athens in December 2021. “You can’t disregard the role education or culture plays for a society developing financially.”

The report advocates modernizing and electrifying Greece’s railroad network in order to connect the region with southern Europe and the Balkans, lowering transportation costs for exporters while increasing the appeal of rail travel for the public. The Greek government announced plans to invest over 4.5 billion euros in the project linking Ormenio with the Greek port cities of Thessaloniki, Kavala and Alexandroupoli as well as the Bulgarian cities of Burgas and Varna on the Black Sea and Ruse on the Romanian border.

The report also emphasized that Thrace’s future advancement is “crucially linked” to the development of the Balkans and the normalization of relations with Turkey. To that end, it suggested increasing regional cooperation on issues like migration and border control and facilitating collaborations between universities, chambers of commerce, municipalities and other organizations. “For this region to flourish, Thrace needs to interact with the other countries and face problems together or find solutions together,” Plevris said.

That is easier said than done. The growth of Greek-Bulgarian relations since the end of the Cold War has been called a Balkan “success story,” and the two countries collaborate as EU and NATO members. But Greeks complain that Turkey continues to carry out provocations, including air violations near Alexandroupoli and aggressive rhetoric questioning Greek sovereignty. “All these years, there’s been the fear of a bam with Turkey,” Chrysoula said. “When Páter Triantafyllos was a baby in the 1960s, our poor grandmother always had a little sack ready to carry him on her back in case we needed to flee to the Bulgarian border. She thought we’d be safe there if something happened with Turkey.”

For its part, Ankara has accused Greece of instigating tensions with baseless claims and supporting an international campaign against Turkey, including trying to block the sale of F-16 fighter jets and modernization kits from the United States. “Don’t try to dance with Turkey,” warned Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who halted bilateral talks with Greece in June.

To help stem the region’s demographic problems, the Thrace committee’s report also proposed subsidized housing programs in northern Evros, including Trigono, and recommended affirmative action policies for public sector jobs in Evros.

Still, tensions also exist within the Evros regional unit. Few believe that economic developments in southern Evros alone will translate into greater prosperity for the north. Some even suspect the growth of Alexandroupoli, Evros’s major port, will further drain the northern villages as workers move south. “Alexandroupoli and northern Evros have different needs,” a city reporter told me. “The north is very agricultural. They make money, but people in the city look down on them. They seem like a lower-class people to us, though we don’t say it loudly.” For the aging residents of Trigono, Alexandroupoli’s sleek, crowded cafes, painted bike lanes and Instagram-friendly art installations 160 kilometers south seem a world away.

The committee approved the report along party lines, with the conservative New Democracy party voting in the majority and opposition parties submitting their own reports. “We agreed on the need; we disagreed a bit on the approach,” Plevris told me.

The lack of consensus frustrated observers like Stavros Tzimas, who covers Thrace for the daily newspaper Kathimerini and hopes that agreement—at least on basic issues—will transform the climate in this nationally and geostrategically significant region. However, “parliament sent out a divisive message about Thrace and it’s a shame,” he wrote.

Living with the border

Meanwhile, since the Ormenio-Haskovo border crossing opened in 1989, the people of Ormenio have learned to live with and across the border. Bulgarians cross in the morning to work in Greek fields and businesses and return in the afternoon. Greeks go to Svilengrad to fill up on cheap gas and cigarettes, have fun at the casino or look for seasonal workers. “It’s a tsigáro drómos,” Chrysoula said, meaning you could get there in the time it takes to finish a cigarette. In comparison, Orestiada, the nearest Greek town, is 45 kilometers away.

But the price discrepancy between the countries has had unintended effects. “I specifically don’t go to Bulgaria like the others,” Chrysoula told me. “The opening of the border created many problems for the region. Because food and gas are cheaper in Bulgaria, that’s where the residents of Trigono went to shop. This led to the closing of shops and gas stations in our area.” Today, only a coffee shop, bar, pharmacy and a mini market remain on Ormenio’s main street.

In addition, many single men from the village married Bulgarian women and started families. “Every day, our sons were going to Bulgaria,” Ms. Xanthoula told me. “For coffee, they went to Bulgaria. One by one, they met girls there. Then they didn’t come home!”

Her son Dimitris Dimitriadis married a Bulgarian woman named Tatiana, and I met the couple when I returned to Ormenio in June. They dropped by to help Ms. Xanthoula slaughter a chicken before crossing the border to visit relatives.

Páter Triantafyllos met his own Bulgarian wife Stefania at a wedding. They married in Plovdiv, which the Greeks call Philippopolis. Stefania had grown up there and studied in Essen, Germany. In Ormenio, she became known as the presvytéra or papadiá, the wife of the priest. They have two daughters, aged 10 and seven.

“Do they speak Greek or Bulgarian together?” I asked.

Chrysoula laughed. “The priest doesn’t know one word of Bulgarian,” she said. “They communicate in German. Stefania learned Greek very quickly. Not that she doesn’t make some mistakes, but she speaks well enough, you can understand her. The girls know Bulgarian, Greek and German. Before Covid, they went to Svilengrad for dance, for exercise.”

During our tour of Trigono, Páter Triantafyllos took me to see his orchard, where he kept his beehives and grew chestnuts, hazelnuts, apples and pears. “I want my daughters to have a small farm so they can stay close to nature,” he told me. He said he thinks that if you maintain a connection to the land, you remain innocent, in a way. “We’re so isolated here,” he said. “We’re used to being in lockdown. But people can’t be alone for such a long time.”

Top photo: Ormenio’s train station used to be a stop on the Orient Express line from Istanbul to Vienna. Immigrants departed the station bound for Germany. Now it receives only one train a day from Alexandroupoli