KATHMANDU, Nepal — At the closing ceremony of the 10th ILGA (International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association) Asia conference, where over 600 LGBTQ+ advocates gathered in late February to network and strategize for the future of queer rights across the continent, a throng of transgender activists stood on stage and asked for a minute of silence. A Nepali transgender woman, unnamed but well-loved in the community, was found murdered earlier that week near Pashupatinath Temple, one of the most sacred Hindu sites in Nepal.

When I first learned of the death a few hours earlier, an intersex activist seated next to me slammed their fists on our banquet table. Heads turned 10 tables away, as the activist’s fury whiplashed from tears back into tremorous rage. They were neither Nepali, acquainted with the victim nor a stranger to queerphobic violence. But this violation of queer life—any life—rattled their entire being, fists on table like thunder in the quiet, post-lunch dining pavilion.

“I need to leave,” the activist said abruptly. As they haphazardly crammed their belongings into various bags, I offered to accompany them from the conference venue to their hotel, mostly in silence. We found a corner booth in a dimly lit lobby bar. A jovial group of off-duty hotel employees greeted us from the adjacent booth, only to slink away, slowly, amid my companion’s loud proclamations against murder. For the next two hours, cradled in our corner of solitude, I patted their back and offered hugs as the rush of emotion eventually gave way to fatigue.

“Why is it so difficult to find somewhere safe for us?” they moaned, face buried in their hands. The smoke of burned sage twirled around their cigarette puffs, wafting upward as though in prayer. Napkins smudged with tears, black eyeliner and beer tumbled across the round marble table. A hotel staff member stole a few glances in our direction, unsure how to serve us. I nodded back every now and then, lacking an answer myself.

That moment—that question—lingered in my mind, both for its profound pureness and the irony that even here, at the largest gathering of LGBTQ+ activists on the continent, all we can do is bow our heads in the wake of violence. This is not a critique of ILGA Asia or the Blue Diamond Society (BDS), the local co-host and Nepal’s largest and most visible LGBTQ+ advocacy organization. To manage the logistical and emotional nightmare of bringing 600 people together, most of whom were in Nepal or attending the conference (or both) for the first time, is no small feat. Indeed, with their leadership and initiative in bringing us together, I found lasting kinship, renewed energy and communal healing across the conference’s five days of panels, receptions and dialogue.

Rather, it was a sobering reminder that to be a queer activist—or queer at all—is to contend with the evolution of crises beyond our control, to grapple with grief on new terms or on a larger scale. Especially across Asia, where autocracy continues to rise and restrict civic space, answers to the most fundamental questions underlying LGBTQ+ movements—our safety, our survival—continue to elude us. At the ILGA Asia conference, I wondered how we could match the scale of these questions with an equitable response—or, how to sustainably build a transnational movement in the scattered corners of possibility that remain.

* * *

ILGA Asia is the Asian regional branch of ILGA World, a federation of over 1,900 organizations campaigning for LGBTQ+ human rights worldwide. There are more than 200 members across West, Central, East and Southeast Asia, whose voices ILGA Asia amplifies and brings to global or regional mechanisms like the United Nations or the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). On a local level, ILGA Asia hosts trainings, crafts digital campaigns (on regional issues such as conversion therapy) and conducts research to inform national advocacy efforts. Since its official establishment at the first regional conference in 2002, ILGA Asia has continued to deepen its intersectional networks and expand its external reach, becoming a flagbearer of LGBTQ+ advocacy on the continent.

As its principal event, ILGA Asia’s biannual conference aims to provide a “vital platform for knowledge sharing and capacity building for LGBTIQ human rights,” according to its website. It remains the largest space for Asian LGBTQ+ activists to pool resources, strategize around similar challenges and enjoy the company of like-minded human rights defenders. For some, it remains the only space where their sexuality can be freely discussed. Activists from Syria and Myanmar, among others, stood up at the end of plenaries to remind us that amid crisis and regime turnover, LGBTQ+ people are often forgotten, left in deep isolation, lacking the room to speak up as they can here.

“Nowhere else could I have access to this level of funders and decision-makers, so I must use every opportunity to share my countrymen’s stories,” one activist from a war-torn country told me, referencing the philanthropic foundations, government bureaucrats and representatives of the Asian Development Bank often in attendance.

This year’s conference, titled “Diversity Dynamics: Unifying for a Just, Inclusive and Sustainable Asia,” was organized around six themes explored over five days: marriage equality, humanitarian crises, LGBTQ+ youth, strategic partnership development, legal challenges and collective action against anti-rights movements. The first two days consisted of “pre-conferences,” facilitated discussions designed for activists whose work or lives directly connected to specific or intersectional identities and issue areas (transgender rights, queer disability rights, inter-faith issues, etc.), followed by three official days of panels and dialogues, with three to five sessions held concurrently at any given time.

Even more than those themes, certain topics occupied at least some real estate in every session I attended, serving as traumatic glue that bound much of the conference and its participants together in shared struggle.

For one, US President Donald Trump’s halt on 87 percent of foreign aid assistance through the US Agency for International Development (USAID) was instantly felt at the conference. After his initial freeze on January 20, the advocacy group Outright International noted that it was forced to suspend 120 grants, ranging from $9,000 to $180,000 in 42 countries with “catastrophic results,” as of a February 2025 report. Many LGBTQ+ groups around the world relied on USAID as entrenched societal stigma and discriminatory laws discouraged local donors from affiliating with such organizations.

USAID’s withdrawal “leaves gaping holes in the oft-fragile support structures for vulnerable communities,” Outright International reported, as legal aid, income generation work and medical care were (and continue to be) suspended. Moreover, with the severe reduction of PEPFAR (President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief), the price of PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis), a key HIV prevention medication, instantly rose in 12 Asian countries.

One media worker and activist from Lebanon was officially laid off just days before the conference. He decided to come anyway, hoping to brainstorm alternative projects that would continue to support the LGBTQ+ community across southwest Asia. As we wandered the streets of Kathmandu in our free time outside the conference, a Pride organizer from Vietnam was notified that he would likely be laid off. He took it quite casually, treating the news as an opportunity to switch careers or enroll in graduate school. (I still wondered if the lack of stability within the Global South’s NGO landscape breeds this kind of flexible mindset out of necessity.)

As I learned at ILGA Asia, however, Trump’s defunding of the LGBTQ+ community was neither an isolated nor inciting incident. Between sighs of exhaustion, activists named the Netherlands and Sweden in the same breath as the US, highlighting a wave of cuts to overseas development assistance (ODA) budgets by conservative governments. Those three, along with Canada, account for over 77 percent of government funding for global LGBTQ+ work. The Global Philanthropy Project (GPP)—which brings together LGBTQ+ funders—estimated in March 2025 that over the next two to three years, at least $105 million in public funding will be at risk, and with philanthropic contributions to LGBTI causes unlikely to rise, a multi-million-dollar funding chasm will separate many activists from their missions.

I’m unsure how many solutions emerged from the conference to address the looming gap. Calls to establish local funding echoed into the distance as choreographed shoulder shrugs and chuckles marked the end of most conversations and sessions about funding cuts. Still, rather than dwell on the despair and hopelessness suffusing the international development and human rights space in early 2025, this year’s ILGA Asia conference created space for activists to commiserate (at the least) and strategize (at best).

The Asia Feminist LBQ Network presented initial ideas around creating a queer feminist fund in Asia. The Asian Development Bank presented its operational approach for the inclusion and mainstreaming of SOGIESC (sexual orientation, gender identity and expression and sexual characteristics) across its programs, with some South Asia-based projects already underway as pilots. Several closed discussions and receptions took place with global and regional funders, but were inaccessible to me and many other conference first-timers.

Outside the sessions, the conference flourished as a platform for connection and mutual aid. Participants generously shared their insights about funding sources and pipelines, including valuable advice about how to approach specific funders. I heard organizers from the Queer Muslim Project and their QueerFrames Screenwriting Lab, funded by Netflix, share insights with folks in other geographies such as China.

That attitude extended to other concerns, such as the lack of SOGIESC data. After the first-ever pre-conference session on disability rights, multiple organizers lined up to chat with Rainbow Disability Nepal, which distributed a detailed report about the design and implementation of a survey on queer persons with disabilities in the Kathmandu metropolitan area.

After another session, a transgender activist from Bangladesh sought out a specialist from the Asian Development Bank, who immediately darted around the venue to help her find a bureaucrat from her country’s Bureau of Data and Statistics. Even as others greeted him while in line for the lunch buffet, pulling him into disparate conversations in three different languages, his eyes would not stop scanning the dining pavilion. “Where did he run off to?” he mumbled about the bureaucrat between hasty greetings and exchanges.

Those were the best forms of solidarity I found at ILGA Asia, little moments of encouragement and dedication to one another’s causes.

At the first-ever East Asia Caucus, organized by Taiwanese NGO representatives, I joined participants from China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, South Korea, Japan, and Mongolia who had informally gathered. We sat in a circle, passing around Korean seaweed packs and stickers as we each introduced our work. We clapped for the small victories we each achieved despite the conservative nature of our societies, from hosting queer film festivals in China for over 20 years to securing legal wins in Japan’s high court for marriage equality. We shared our plans for regional collaboration, from LGBTQ+ family initiatives to gender-inclusive curricula.

During a tea break, I asked Mehrub Awan, a Pakistani multi-hyphenate—transgender activist, policy practitioner, physician, and artist, among other identities—what her work in what she called feminist espionage entailed. “This is what it is,” she said as she gestured toward a table of queer and trans Pakistani friends. Over the last two years, they had implanted themselves across the many aisles of the Pakistani parliament, sneaking issues of gender and LGBTQ+ rights into conversations with politicians and decision-makers and attempting to indirectly influence their views. Our conversation drifted from strategies and tactics for engaging across political differences to critiques of neocolonialism, especially as it applies to the US-Taiwan relationship, and ended—as with most conversations at the conference—with a promise to share a drink or dance together later in the week.

“LBQ groups have not had money for so long, they’re paying for the activism with their blood and sweat,” Jean Chong, founder and executive director of the Asia Feminist LBQ Network, said in an interview with GiveOut. Chong elaborated that queer activists have long grown accustomed to hustling against all odds. Indeed, the odds have only become higher, with LGBTQ+ rights continuing to slip as an international development priority for many nations.

But the hustling continued into the ILGA Asia conference. Slowly but surely, through small connections and moments, it felt as though we were weaving the safety net to hold one another against the ripples of fascism from the West. Perhaps that is the value of transnational connection: Despite the limited networks that exist in our hostile states, we can connect and relate to something bigger than ourselves.

When I first arrived at the registration desk, the Intersex-Inclusive Progress Pride Flag billowing at full mast outside the five-star Soaltee Hotel, I watched attendees exchange kisses on the cheek, hugs and the pursed smirks of friends with history. And by the end, it all made sense to me.

* * *

In writing this dispatch, I’ve danced around the word “solidarity.” Although it appears only once so far, I was hesitant to use it even then, fearing the word might lose meaning from overuse and overpromise.

Part of my hesitation stems from the conference itself.At the mere mention of “solidarity,” folks cheered and clapped more enthusiastically than during any other moment in the sessions. It felt too easy; in the face of repressive regimes and an international development industry that categorizes and separates causes into distinct categories, to vaguely call for solidarity felt naïve. Yet I also knew these were cries for support and recognition by LGBTQ+ rights defenders starved of such backing within their own countries—a cry I recognized and empathized with.

In some cases, activists were specific in their requests for solidarity. One participant from Myanmar distinguished solidarity from a savior complex; a disability rights activist urged us to include the voices of disabled people in data collection and funding requests, to uplift marginalized communities within the LGBTQ+ population. Solidarity was positioned as a strategy against the global anti-gender movement—another thematic thread that floated to the top of people’s minds—as activists shared counter-surveillance, anti-censorship and security training methods to prepare for possible attacks.

But beyond the walls of that five-star hotel, inundated with our domestic struggles and affairs, it wasn’t clear what solidarity could look like in practice. It seemed to rest on the idea that our shared identities as LGBTQ+ people in Asia were enough to bind us together.

However, more common was a recognition of the fact that Asia is an assemblage of vast geographic, cultural and historical diversity. While celebrated during receptions and ceremonies, that diversity also overshadowed the conference as loose divisions between the 600 participants.

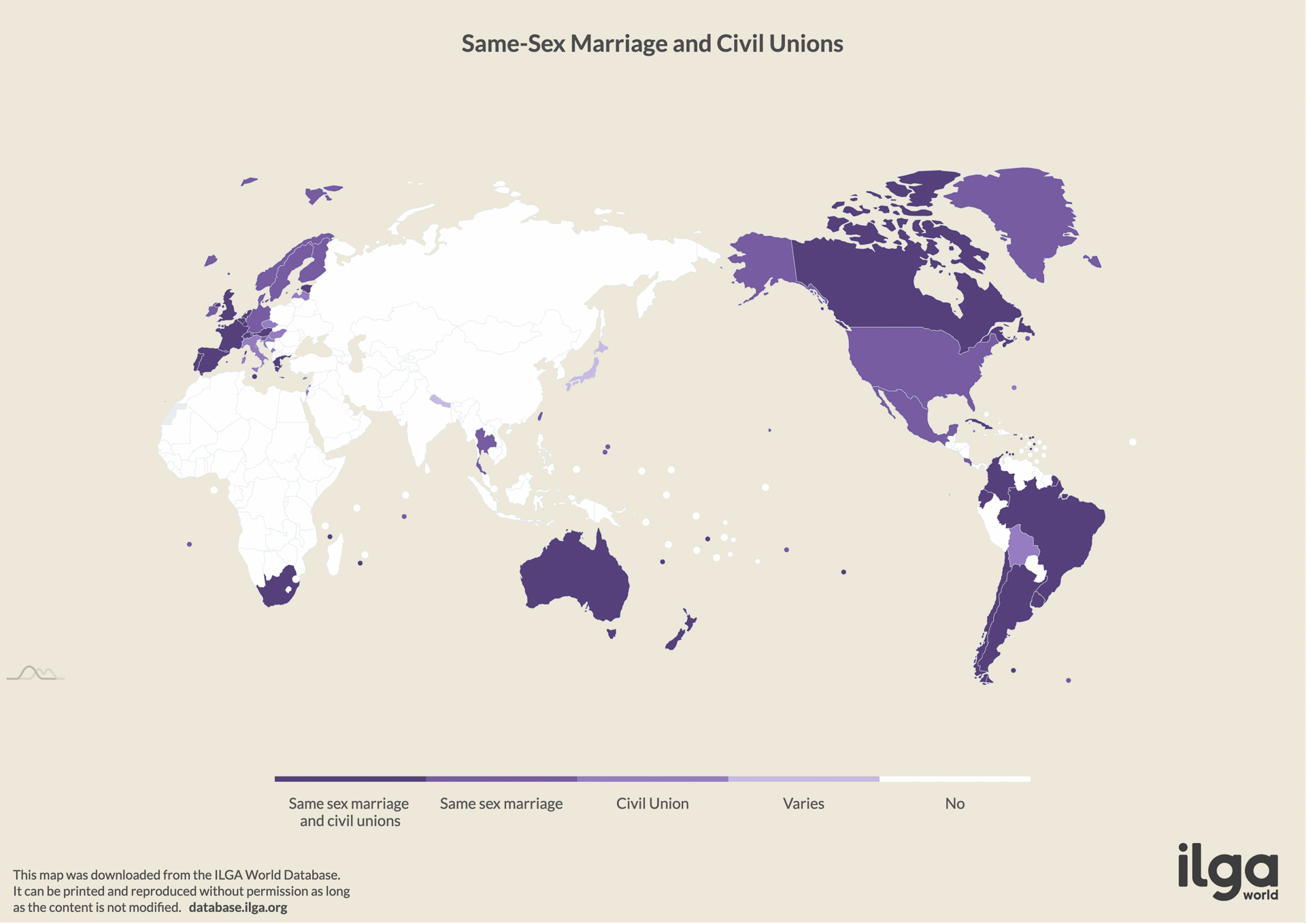

Indeed, in his opening speech, Graeme Reid, the United Nations Independent Expert on sexual orientation and gender identity, alluded to the range of Asia. On a positive note, he said, marriage equality movements have succeeded in Taiwan, Thailand and (provisionally) Nepal, alongside constitutional advances toward equity in Japan and South Korea. Singapore joined the ranks of countries to decriminalize homosexuality in 2022.

But LGBTQ+ identities remain criminalized in over 20 countries in the region, with a range of punishments from jail time to death penalties in place across the region. Colonial-era persecution laws persist in Bangladesh, Myanmar and Malaysia, while countries like Iraq and Kazakhstan have both legislated new civic or criminal codes that discriminate against LGBTQ+ identities. Broadly, attempts to pass anti-discrimination laws that cover SOGIESC as protected categories have failed or become deprioritized in the face of anti-gender movements.

Moreover, across these geographies, factors such as colonial histories, religion and politicized cultural norms weigh differently. During one of the pre-conference sessions on interfaith dialogue, participants exchanged their experiences with anti-gender ideology in religious or spiritual contexts. Folks shared their experiences as queer Buddhists from Southeast Asia, Hindi cis gay men from India, Muslim transgender women from Bangladesh—the list of distinct intersectional identities goes on. The conversation ping-ponged between forced conformity, internalized shame and religious exclusion or excommunication, throughout which participants affirmed the need to toughen their skin in the face of obstinate institutions.

Reverend Reina Ueno wrote in her reflection on the session that “everyone engaged positively, creating a space for collective healing and action.” Indeed, I could feel participants heal through kinship and storytelling during the discussions. The American community organizer and racial justice scholar Prentice Hemphill describes healing as “any set of practices that restore a felt sense of safety, the capacity and desire to belong, and a sense of dignity as evidenced by a reduction of shame and increase in agency”—essential precursors for social change.

But while I left with a greater understanding of the diversity of experiences that undergird the intersection of religion and sexuality across the region, it wasn’t clear how the bricolage of stories could “inspire and guide action,” to use Hannah Arendt’s definition of solidarity. Indeed, that was a common theme across the conference’s sessions. One discussion about strategic litigation for transgender rights in Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea and Japan provided some of the conference’s most in-depth insights into each country’s legal context. Another session described efforts to create more LGBTQ-friendly school environments in Taiwan and Thailand. The sessions often stopped after providing descriptive summaries of the current challenges and campaigns. Fatigue began to set in over the course of the conference. We ran laps around an ever-expanding collage of domestic and transnational quandaries, but the solutions remained elusive, unfunded dreams.

The social movement scholar Matthew Farmer warned in his research on UK-based LGBTQ+ organizations and their role in transnational advocacy that “what is problematic is the way in which assumptions about the primacy of shared experience constitute a supposed political solidarity without contesting the generalized, conceptual basis of such ‘experience’ and ‘difference.’” At first, I worried the ILGA Asia conference would conclude with vague calls for solidarity and platitudes about our shared struggle. By the end, I wondered how we’d move emotional connections and bonds into action-oriented solidarity that wouldn’t fall into a trap of universalism or cultural relativism.

In the introductory sections to ILGA Asia’s Strategic Plan 2021-2025, the organization notes: “Collective actions can bring about changes at scale, arenas need to be maintained to ensure opportunities exist for LGBTI activist and allies can connect across sectors and localities, exchange experiences, learn from each other and advocate for change through networks and coalitions.” The conference fulfilled many of those preconditions for action, providing a platform for exchange, connections and deep emotional bonds rooted in solidarity. But across the diversity of concerns and priorities peppered across five packed days—across the material obstacles to change that remain unmoved—I often wondered what we were building toward.

* * *

Some of the people I spent much time with at the conference were migrants like myself. Of course it reflected my own identity as someone careful to introduce himself as “living in Taiwan” rather than “from Taiwan.”

One Chinese activist, beyond their personal work as a performance and visual artist, organizes the queer Chinese diaspora in the United Kingdom. Another is a photographer and somatic coach based in Brooklyn, which led us to a classic conversation about mutual friends and overlapping timelines.

In my discussions with both of them, one common theme was an uncertainty of affiliation: In a conference so heavily oriented around national identity and region, how should they introduce themselves? Neither has returned to China in more than a decade, and had no lived experience to back any claims about the countries of their passports. Neither was present at the event’s East Asia Caucus—from a lack of desire and invitation.

Of course, that did not mean we did not find belonging and kinship; to be among a mass of other Asian queers was “enough of a healing experience,” as one of them told me. To drift between lunch tables and sofa clusters occupied by people speaking the same language from the same regions of the same countries was not as alienating as it was revealing about the messiness of transnational solidarity.

Indeed, national identity often took center stage in terms of how we related to one another on the conference grounds. Small talk at lunch tables or before a session often began with the same script of questions: Where are you from? Are you familiar with my country? Have you ever visited? How bad is the situation where you are from? Were you affected by funding cuts?

National identity also shaped some activists’ understanding of one another. One Southeast Asian participant told me their colleagues often view Taiwan with distant admiration. Although Taiwan may be a leader in LGBTQ+ rights, many activists across the region feel the island nation’s lessons may be challenging to translate beyond its own democracy, human rights reputation and economic liberalism. “I often see the Taiwanese activists at their own table, in their own world,” someone told me, with slight surprise that I floated around the conference largely with others.

Session titles often referred to specific countries or regions, creating essential spaces for activists within those regions to network and exchange ideas. However, it was more uncommon to find people crossing regional lines. I often found myself looking at panelists and wondering if insights were meant to be country-specific.

The aforementioned panel on strategic litigation in East Asia was attended exclusively by folks from the countries represented as well as friends of the speakers. The session on queer art, sponsored by the Queer Muslim Project, was primarily attended by people from South Asia. At the closing ceremony, a Bangladeshi woman next to me noted how a noticeable number of new board members, elected during the conference, are Pakistani.

Much of that was perhaps unsurprising. Of course, participants gravitated toward friends and longtime collaborators from their home countries. Moreover, they are constrained by the primacy of the Westphalian system, which informs the funding structures and NGO industries within which they operate. Some comments reproduced broader geopolitical or economic asymmetries, from East Asia’s relative wealth and privilege compared to many other parts of Asia or the different development paths in South Asia.

None of the actions were malicious or intended to undermine the possibility of transnational advocacy and solidarity. However, in a shifting world order where funding cuts force organizations to focus their efforts, national and regional borders cut through the ways we related to one another on the conference grounds.

Still, I wonder how compatible these reified lines of national identity are with the “queer coalitional politics” the Taiwanese sociologist and political scholar Lee Po-han animated in his reflections after the 2015 ILGA Asia conference. “To what extent can we highlight the liveability and counterpublics constituted by queer and other outcast populations rather than the focus on the states, their developmental and economic conditions, and their centralized legislations and policies?” he asked. In other words, rather than remain in the siloed possibilities of how to improve LGBTQ+ livelihoods, how can thinking more broadly, across “Queer Asia,” help bring about alternative ways to improve livelihoods? How might a conference like ILGA Asia encourage its participants to think not only about working better in our respective contexts but also about assembling and pooling our resources across contexts?

After the 10th ILGA Asia conference, emotional bonds with new friends continued after our time in Nepal. They rested in a panel on queer art hosted by the Queer Muslim Project, where a Nepali transgender woman dragged me by the hand into a dance during a rap performance. They rested in the Arts and Culture Space, co-organized by ASEAN Sogie Caucus, the International Planned Parenthood Federation, the Queer Livelihood Project, ILGA Asia and the Blue Diamond Society, where visual art, film and storytelling spoke across borders.

They rested in a panel discussing the economic costs of discrimination, where economists and other scholars from various multilateral development banks shared tangible best practices in data collection and analysis, creating a platform for people to build on in their local contexts.

In The Scholar and Feminist Online, an academic journal about feminist theories and women’s movements, Brenna Munro and Gema Perez-Sanchez describe “minor transnationalisms,” or “border-crossings at more intimate, affective, aesthetic and informal levels—that is, through lateral and nonhierarchical network structures.”

I wonder how many such minor transnationalisms come together to make a major, material shift for queer livelihoods.

* * *

On the conference’s first day, during a tea break after pre-conference sessions, I chatted with a representative from Transmen Indonesia, his country’s first transmasculine support and advocacy group established in 2015. In the last decade, their organization has been able to host community support sessions across Indonesia’s many islands and even support seven people in their escape from conversion therapy.

However, since the Indonesian state continues to pathologize transgender identities and fails to recognize LGBTQ+ non-governmental organizations, they can’t formally undertake more programming or advocacy work.

“Does anything give you hope under those circumstances?” I asked with the innocence of a first-time conference-goer.

“Hope?” he said, guffawing. “I don’t know about hope but I know that someone needs to be doing this work.”

On leaving Nepal to return to Taiwan, this activist’s words also reflected the ILGA Asia conference itself. The conference attempts to do the impossible: bring together activists operating under a wide range of circumstances, all with immense resource constraints, while deeply oppressed by state and anti-LGBTQ+ actors. Transnational connection feels flimsy as activists absorb the shock of external actors, including the US and the outsized influence of the anti-gender movement. The Global Philanthropy Project reported in 2024 that the reported income of three global anti-LGBTQ+ organizations exceeded that of over 8,000 LGBTQ+ organizations around the world.

But as Henry Koh, the executive director of ILGA Asia, mentioned during the conference: “In this city cradled by the Himalayas, we are reminded that mountains are not just landscapes. They are symbols of endurance, standing tall against time and tide. And isn’t that what it means to be queer in Asia? To exist in a world that tries to erode us, yet remain unshaken?”

Leaving ILGA Asia, I saw a mountain range forming on the horizon. The contours of transnational LGBTQ+ solidarity on the continent are still hazy, still outlined by the web of personal relationships and deep empathy that forms as a result of this biannual conference. I am not naïve enough to believe that a transnational movement will form over five days or even five years. But in the uphill battle for LGBTQ+ rights across the continent, I’m eager to get closer to the mountain range, to trace its peaks and valleys and follow what becomes of this network.

Top photo: Representatives from Taiwan, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, China and Mongolia at the East Asian Caucus