In 1922, as the Age of Empires was fading and America emerging as a great power in the aftermath of World War I, a 22-year-old Harvard graduate named John O. Crane settled in Prague to become personal secretary to the first president of independent Czechoslovakia, the philosophy scholar Tomas Masaryk.

It was not entirely by chance. Crane’s father, the diplomat and philanthropist Charles R. Crane, was a supporter of Masaryk’s and champion of his successful bid for the new country’s statehood from the ashes of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918. Charles Crane had helped secure crucial backing from Washington, where he was a close friend and adviser to President Woodrow Wilson.

Masaryk went on to be overwhelmingly elected three times, serving in office until the end of 1935, when he left behind the strongest democracy in Central Europe. His ascendance was validation of the new US role in the world a century ago, advocating national self-determination, freedom and democracy in a direct challenge to the old imperial order.

Still, both Cranes were concerned about Americans’ lack of knowledge about most parts of the world. So they launched a small operating foundation in New York in 1925 called the Institute of Current World Affairs together with a colleague, the journalist and lawyer Walter S. Rogers. He was a champion of press freedom whom President Wilson had appointed to lead a short-lived project to oversee an international network of news agencies aimed at breaking the news wire monopoly (it didn’t work).

The three men believed that making sense of the complex new order of emerging democracies—together with informing America’s role in the world—would demand what John Crane characterized as rigorous “modern intellectual training.” Their new organization, ICWA for short, would send a handful of fellows abroad for years of travel and study with the aim of creating a small corps of experts, as Rogers wrote earlier that year, “each being the best-informed person in the world about the affairs of some great area, and… taken together, including within their purview the entire world.” They would advance American understanding of global cultures and affairs by informing policymakers, media, corporate bosses and the American public.

Charles Crane would endow the institute with $1 million, John Crane would become its first fellow and Rogers would go on to serve as executive director until his retirement in 1958, mentoring an outstanding group of young scholars, journalists, diplomats and others who would report on global developments firsthand and help establish the study of international societies at Columbia, Harvard and other universities. Remarkably, ICWA is still carrying out its original mission, seeking out and mentoring highly promising young professionals who undertake two-year independent writing fellowships abroad, many of whom go on to become leading experts on their topics and regions.

Even more remarkable, however, is the abrupt change in America’s role in the world during ICWA’s centenary year. From the aim a hundred years ago of advancing international liberalism and self-determination, the country is now on the verge of ending its own democratic experiment together with its global leadership.

A nativist would-be autocracy is undermining faith in objective facts and public debate, extracting personal loyalty from State Department and other officials, and destabilizing the global economy. Leveraging his power for huge personal profit from foreign governments and businesses, the president now attacks our closest allies, openly sympathizing with authoritarian leaders. The fellow travelers are working to return the spheres of influence that dominated 19th-century geopolitics before the cataclysms of two world wars and a global depression gave rise to the 20th century’s international order and America’s role as leader of the free world—however imperfectly it’s been pursued.

It is with that reordering of priorities at front of mind that ICWA is launching this journal about global cultures and affairs. Of the mistakes the United States has made in the past century of foreign policy, many were fanned by failures in understanding how we were perceived abroad or where our actions might lead, whether in the Vietnam War, or by fomenting a coup in Iran in 1953 or invading Iraq in 2003, to name just a few. Part of the institute’s aim has been to help develop such understanding of what others think about us.

Compass will reflect on the fate of liberalism in a new era, and how the United States, its policies and actions are perceived abroad. We’ll feature writing from ICWA alumni and other contributors about global issues, culture, society and travel, as well as reviews, photography, art and excerpts from the institute’s archive of fellowship dispatches over the last century.

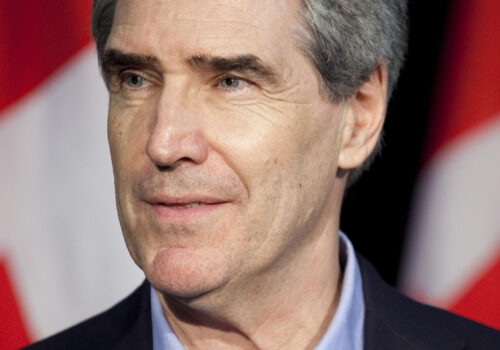

This first installment includes an incisive interview with the historian and politician Michael Ignatieff about the direction and historical precedents of the current turn in global politics. Harper’s magazine contributing editor Matthew Stevenson travels to the killing fields of Sri Lanka’s civil war. AEI’s Dalibor Rohac analyzes the possible return of Czechia’s former prime minister, the populist oligarch Andrej Babiš. The composer Roger Reynolds ruminates about the relationship between performers and audiences, and the Germany scholar Ritchie Robertson writes about the relevance of Kafka’s The Trial a century on.

This project isn’t exactly a new departure for ICWA. Before settling on what would become the institute’s fellowship program in 1925, John Crane and Walter Rogers initially envisioned an international information agency to be called the Mutual News Exchange—not to report news but rather provide deep contextual analysis based on the kind of first-hand experience of the world they believed should inform decision-making. The motto was “Truth will conquer.”

As we hope to expand, and add podcasts and other features, we’ll also be guided by the aim of building our community, not only of former fellows but all contributors, friends and readers.

There’s been plenty of cause for dark pessimism before, needless to say. Before his death in 1937 and the Nazi occupation of his country the following year, Masaryk became one of the first world leaders to sound the alarm over Adolf Hitler’s rise in Germany. By then, Charles Crane had become deeply disillusioned about the direction of global affairs before he died in 1939.

Now, amid the biggest challenge to the postwar liberal democratic order, America is in retreat, turning away from the promises of the 1920s, with all their manifold imperfections. It is up to European and other countries to lead, and at home—where institutions are being undermined or simply eliminated—falling to democratic citizens to do what they can to develop new visions and strategies to ensure the country and its foreign policy can once again become a force for good. To that end, ICWA’s mission is as important as ever, and the idea for Compass is to help advance it.

Read Compass on Substack

Illustration: “Diving In” by Bryn Barnard