ABUJA, Nigeria — Fourteen-year-old Chioma just recently began menstruating. Her father sits in his village compound with five male friends who happen to be local chiefs to discuss her coming of age and make plans for a special ceremony. “Finally my daughter will be welcomed fully into womanhood and I can start entertaining suitors,” he says of expectations she will undergo the ritual cutting of her genitalia, a practice called female genital mutilation. His friends congratulate him on the milestone and one says, “so your tiny daughter of yesterday will soon become a fully grown woman, that’s good—oh, the gods be praised!”

Later that night, Chioma’s father discusses the plans with his wife. She looks at him, worried, and says, “My husband, please just think about this for a minute, our daughter is not ready for this, let’s not expose her to such an experience, please.” Angry, he yells, “I should have done this when she was a baby but you wanted her to grow up. When she turned 10, you said 16! What, again?! Woman, do not disturb me!”

The wife goes on to tell him about the menstrual and labor pains she experienced as a result of having gone through female genital mutilation herself. But he’s made up his mind. He says he doesn’t want to be the town’s laughing stock. “Woman, just let me be, what do you want from me? All my mates are telling me of the different men indicating interest in marrying their daughters and here I am, no one has even asked if I have a daughter simply because she has not been cut and made a complete woman… [I’m] done discussing this with you, she will be circumcised in the next full-moon festival and that’s final! Anyway, has painful menstruation ever killed anyone?”[1]

The scenario above, based on a true story, is from a stage play I attended in Abuja organized by a non-profit organization called Active Voices. It details just one family’s experience with the decades-old tradition of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) as practiced in southeastern Nigeria.

It is a massive problem. One in four Nigerian women between the ages of 15 and 49 years has experienced FGM, making the country number three in the world following Egypt and Ethiopia, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates.[2] Some 19 million women in Nigeria have undergone FGM. Like Chioma, three million girls in Africa are at risk of being cut each year. More than 200 million girls and women have been mutilated in Africa, the Middle East and Asia, according to the WHO.3

FGM takes place in both urban and rural communities; it is a social norm that “transcends religion, geography, and socioeconomic status,” the WHO says. The practice is most prevalent in the southwestern (Yoruba-speaking region) and southeastern (Igbo-speaking region) parts of Nigeria at 47.5 percent and 49 percent of women cut, respectively.3 The states with the highest prevalence of the practice are Osun (76.6 percent) and Ebonyi (74.2 percent).

This newsletter is the first of two exploring FGM/C in Nigeria, providing an overview of some individual experiences in the capital. I’ll explore FGM/C in greater detail in another newsletter, looking at southwestern Osun state, where the practice is most widespread.

FGM/C in Abuja

FGM/C “involve[s] partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons,” according to the WHO. It is not a topic you hear about in everyday conversations in the politics-saturated capital. But it shadows many who have experienced the practice in their hometowns and now live in Abuja.

During the stage play, a young woman sitting next to me named Kemi confided that she had been cut as a child at three days old. Her family is from Ondo town in Ondo state (just below Osun, with the highest rate), where FGM remains a tradition. Six feet tall, dark and slender, the model-like Kemi is 28 years old and works in Abuja. She discovered three years ago from her mother that she was cut as an infant. Kemi is one of three girls in a family of five children; both her sisters also underwent FGM/C. Although her mother is formally educated with a polytechnic college degree in accounting, she agrees with the cultural belief that “a child’s head must not come out of a vagina that was not cut.”

For Kemi, who is single, FGM/C has mainly affected her sexual experiences. “When touched, I don’t feel that urge quickly,” she says. “The sexual act is not enjoyable. It’s like someone is intruding in my body.” She does not know what type of FGM/C was performed on her, but she tells me that her labia looks different from normal labia she has seen. Kemi’s elder sister, who is married, had to deliver her two children by caesarian section because of complications from her FGM/C. As a result, her sister did not cut her own daughter when she was born, resisting her mother’s advice. The baby’s father also comes from a different state where FGM/C is not practiced. “I don’t think FGM is necessary,” Kemi says. “It’s a constant reminder of how I was tampered with. I don’t think the practice is right.”

Another woman described coming under pressure to undergo FGM/C when she was already pregnant. Doutimi Egbuson is a 40 year-old mother of two children from Bayelsa state in the Niger Delta region. She says her mother wanted her to be cut to “pass down the tradition.” When Egbuson objected, her mother insisted on going ahead with the ceremony that takes place after FGM/C to make it appear that she had undergone the process. Coincidentally, the date the mother chose for the ceremony happened to be the day Egbuson delivered her baby, enabling her to avoid taking part. Less fortunate women in her village are forced to suffer FGM when they are seven months’ pregnant.

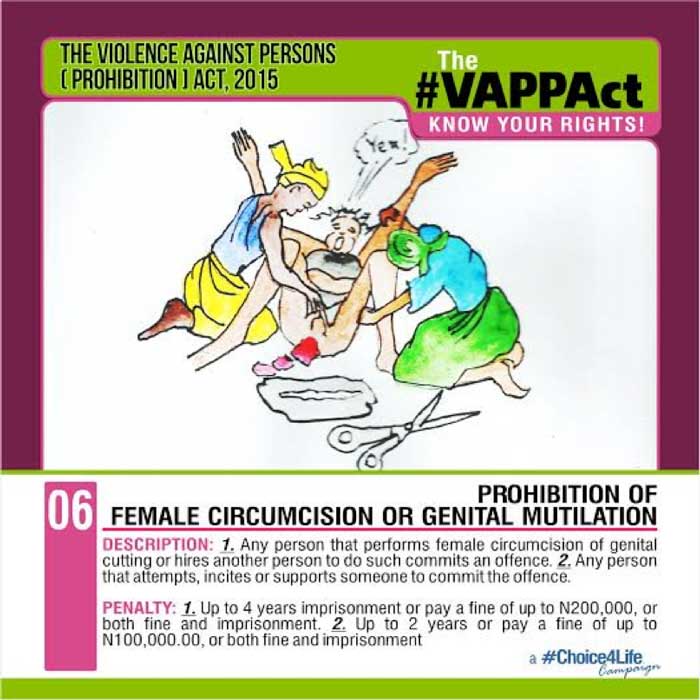

Government policies on FGM

FGM/C is illegal in Nigeria. In one of his signature achievements in 2015, President Goodluck Jonathan enacted a law called the Violence Against Persons Prohibition (VAPP) Act, which “seeks to eliminate female genital mutilation as well as all other forms of gender-based violence.” On paper, FGM/C is acknowledged as a form of oppression toward women and girls, but in reality, many value the tradition. Prior to the legislation’s passage, Osun state had outlawed the practice, one of 11 of Nigeria’s 36 states to take the lead. However, the fact that Osun has the current highest FGM/C prevalence in Nigeria shows that culture and tradition have a greater impact on behavior than the law.

Why FGM/C Exists

No known traceable origin exists for FGM/C. The practice has been sustained for different reasons, including the stated need to maintain virginity, protect against barrenness, as a rite of passage, to follow social norms and for economic value. In many cases, the practice continues simply because “it is tradition.” As a circumciser from Osun state said in an interview, “I was born into this practice. I do not know the history; but I can say it is as old as the tradition of tribal marks on faces.”3

FGM/C also remains prevalent in many communities as a mark of superiority. A gender specialist in Abuja, Nkiru Igbokwe, told me that it is a matter of pride to be able to pass down the tradition across generations. In most of the communities where FGM/C is practiced, “people know who has or has not been cut,” she said, with stigma attached to those who have not been cut. Some communities believe a baby will not survive if its head touches the mother’s clitoris.

Patriarchy, specifically the need to control a woman’s sexuality and pleasure, is principally responsible for the practice of FGM. If a girl is cut, she is believed to be less promiscuous and more suitable for marriage. A woman who has been cut is presumed more likely to remain faithful to her husband. However, that is not always the case and sometimes produces a counter-effect. As Egbuson told me, a man might not desire a wife who has been circumcised because he won’t enjoy sexual intercourse with her. “FGM makes men leave their wives because they are not satisfied with the sexual experience,” she says. Despite the high prevalence of FGM, Osun state has very high rates of teenage pregnancy.

Not all men support FGM, however. Several told me they weren’t even aware FGM still takes place and that they do not support continuing the practice. It’s a very complicated issue for other reasons, including the fact that while FGM is a product of traditional laws instituted by male leaders, highly respected women in society are sustaining the practice today.

Does FGM benefit anyone? The general response I’ve received is no. However, because FGM is perpetuated in order to control women’s sexual pleasure, many believe men to be the main benefactors. I put that question to Ikenna Nwakanma, a public health practitioner in Abuja. “If you feel FGM is made to benefit a particular set of people, it means you are alluding that those who benefit from it must be the ones influencing the practice,” he said. “FGM benefits no one, honestly, men do not even know the difference.”

FGM does provide social and economic benefits to families and circumcisers who earn their living by cutting women and girls. Those who undergo FGM are celebrated and, as the play above illustrates, the practice confers higher social status on families. Egbuson tells me that sustaining the practice gives many women a sense of purpose and pride by passing down their tradition. Women assume that “because I experienced it, you too should experience it,” she adds. The social value overshadows the pain or denial of rights associated with FGM/C.

So what role do men play in sustaining FGM? “The men are the preservers of the culture, but the women are the implementers,” Kemi says.

Efforts to end FGM in Nigeria focus heavily on influencing men to stop the tradition. A young male anti-FGM advocate named Harrison Emu who works in southern Delta state told me via email that “the key to pushing for abandonment lies with the custom upholders in most African communities… the chieftains are male and they are the major guards of tradition who are primarily responsible for instilling the doctrine of FGM/C and other long-held traditional beliefs.”

Why do women, the implementers of the practice, continue to sustain it? Many parents teach cultural and religious values to girls and women dictating that men have the final say, Kemi says. Hence, if men demand that a tradition should continue, so it goes. “If you are married, you put your husband first in everything because you don’t want to lose him and everything that comes with being associated with him,” Kemi says with a look of disappointment.

Perceptions of FGM/C are also contextual. Ikenna told me that during workshops in Anambra (southeast) and Benue (middle belt) states with female religious leaders and champions against gender-based violence, he observed that “the women themselves confirmed that in recent times, FGM has been practiced and promoted and enforced by the women.” Doutimi Egbuson agrees, saying ending FGM begins with educating women about their human and reproductive health rights. “If a woman knows her rights, that [FGM/C] tradition will be nullified.” She cites herself as an example. However, many Nigerian women are not empowered enough to speak out and remain silent for fear of being seen as challenging authority or being wayward.

In some cultures, FGM/C is called female “circumcision” in the belief that it must be carried out to beautify female genitalia. In those communities, uncircumcised girls are not seen as part of society and may not be able to find husbands. Because of the significant value accorded to being married and the social prestige the practice brings to families, many adolescent girls are forced to tolerate the pain with little thought about the potential long-term implications. Egbuson told me that in her village, circumcised girls are not allowed to take their baths in the river because they will upset the god of the river, a crocodile. That is one way of distinguishing those who haven’t undergone FGM.

FGM/C Classification

Four types of FGM/C procedures are typically carried out.

A clitoridectomy involves removing some or all of the clitoris. The second type, known as excision, is the removal of some or all of the clitoris and the labia minora (the folds around the vulva). The third, known as infibulation, involves the narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal. The seal is formed by cutting and repositioning the labia minora, or labia majora, sometimes through stitching, with or without removing the clitoris. The last type includes any procedure done to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes.

All four types are practiced in Nigeria. The procedures are typically carried out by elder women in communities who serve as custodians of the tradition and information about the practice. The circumcisers typically have little to no formal education or medical training.

Complications from FGM/C

The full impact of FGM/C is often not known. Many women and girls suffer complications in silence. FGM affects girls and women psychologically and physically, with immediate and long-term implications. FGM/C can cause girls to have low self-esteem when they know their bodies have been tampered with, and the practice affects women’s reproductive health. Because non-medical professionals usually carry out FGM/C, the procedure is often done in unsterile conditions using instruments that are shared between victims. That poses a risk of HIV and other infections. Some girls also experience painful urination and menstrual cycles from suturing the vagina, leaving only a tiny hole for the passage of urine and blood. The practice contributes to maternal mortality and fistula (a hole between the vagina and rectum or bladder that causes uncontrollable discharge of urine or feces) as a result of complications during childbirth, including heavy bleeding. That’s especially true for pregnant women who go into premature labor at seven or eight months when their wounds from FGM/C haven’t yet healed.

An end to FGM?

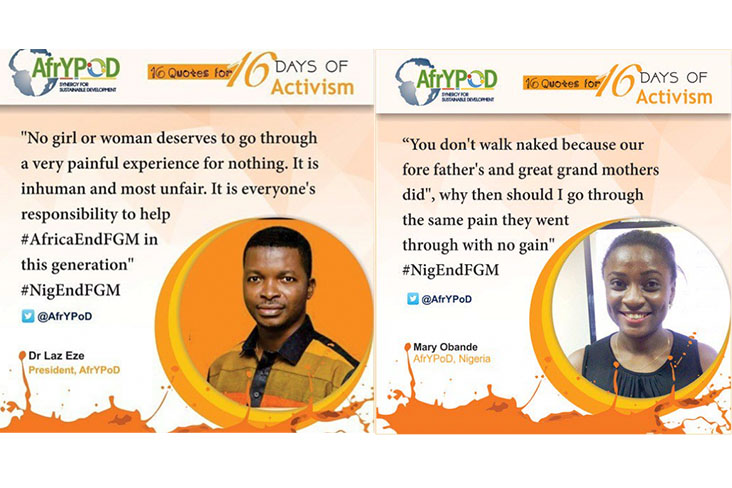

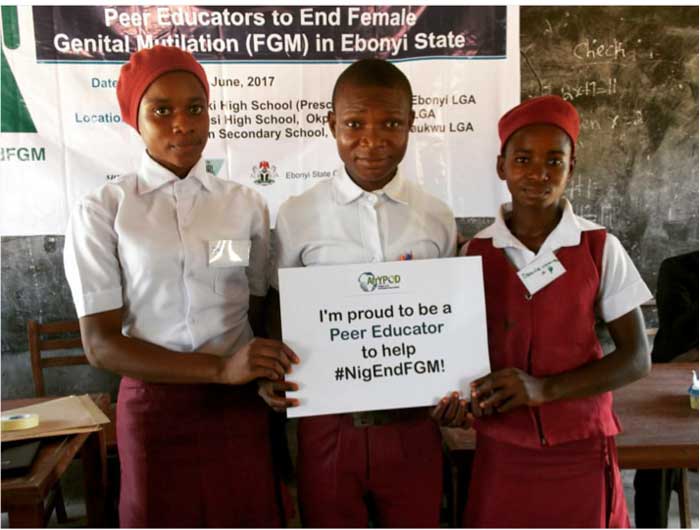

Youth-focused organizations such as Active Voices, The Girl Generation, African Youth Initiative on Population and Development (AfrYPoD) and the United National Population Fund (UNFPA) are taking the lead in ending FGM/C in Nigeria. Their advocacy activities, like the drama described at the beginning of this newsletter, are providing education to communities about the existence of FGM/C and its harmful effects.

Nigeria is also part of the UNFPA’s global campaign on zero tolerance and abandonment of FGM/C. Circumcisers are being asked to take a public pledge denouncing and abandoning the practice. The effort includes awareness and sensitization workshops carried out in schools to ensure that young Nigerians do not continue the practice when they become parents. But such programs face massive challenges.

In my next newsletter, I’ll dig deeper into the specifics of FGM/C in Osun state.

Photo Courtesy: AfrYPod

[1] Adapted from Stage Play by Active Voices: “Together” – one community’s story of ending FGM. August 2017.

[2] Nigeria: Female Genital Mutilation – Recalling the Agonising Pain. http://allafrica.com/stories/201603250153.html. Accessed: 08/20/2017

[3] UNFPA/Action Health Incorporated. FGM/C in Nigeria: Telling Stories, Raising Awareness, Inspiring Change.

[4] http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs241/en/. Accessed: 07/16/2017

[5] UNFPA/Action Health Incorporated

[6] WHO

[7] Nigeria’s bill targeting FGM is a positive step, but must be backed by investment. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2015/may/20/nigeria-fgm-gender-violence-bill-investment. Accessed: 08/21/2017

[8] Nawal M Nour. Female Genital Cutting: A Persisting Practice. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2582648/. Accessed: 08/20/2017

[9] Nigeria: Female genital Mutilation. https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/FGM_.pdf. Accessed: 08/21/2017

[10] World Health Organization. Female genital mutilation. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs241/en/. Accessed: 08/21/2017

[11] Lola Alonge. Nigeria: How to End FGM in Nigeria http://allafrica.com/stories/201511190708.html. Accessed: 08/21/2017