PARIS, France — One drizzly January afternoon, I stood outside Folies Bergères, a theater in the city’s ninth arrondissement, waiting in a line that went around the block and overtook neighboring streets. Police tape blocked surrounding roads; cops with bulletproof vests and intimidatingly large weapons patrolled the area. When I finally made it to the entrance, security guards searched my bag, patted me down and scrutinized my New York I.D.

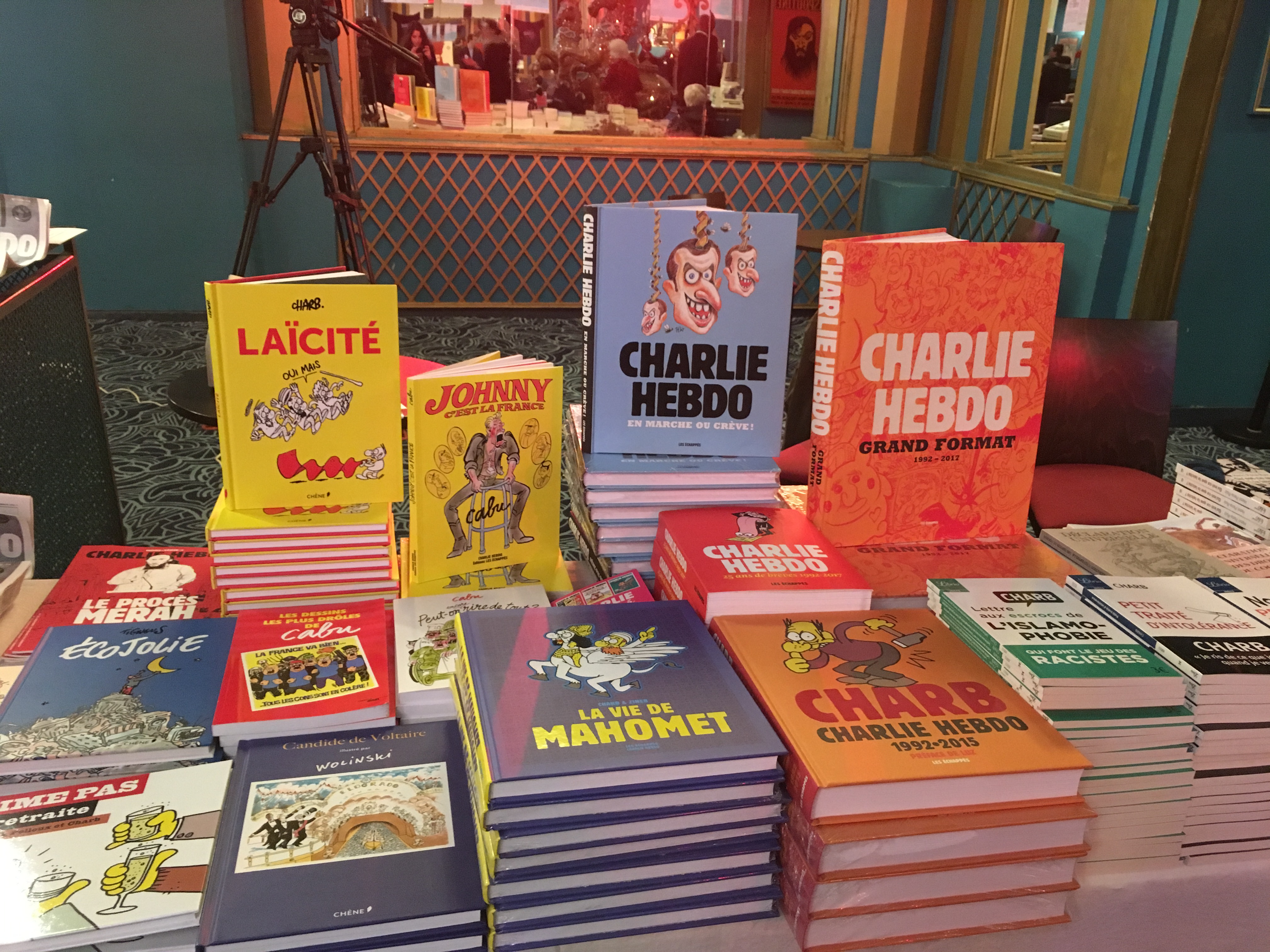

It was the day before the third anniversary of the attacks at the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo. An eager audience of nearly 2,000 had elected to spend its Saturday at Toujours Charlie!, or “Always Charlie!” a conference organized by the Printemps Républicain—the Republican Spring—a movement founded in 2016 by a group of academics, intellectuals, politicians and journalists. It was created in response to the terrorism that struck “the Republic and its principals” in 2015 and 2016, according to its mission statement.

Its members defend “the common”: the universal, shared identity at the heart of the French Republican ideal. That value, the Printemps Républicain argues, is under siege from groups that seek to “put their own identity in the spotlight,” as the political scientist Laurent Bouvet, a cofounder of the movement, told me. “No,” he said emphatically, responding to himself. “We can’t have people saying they want to be recognized uniquely as one thing or the other because then there’s no common. We can’t build the ‘common’ on the differences we project in the public space. Everyone needs to make an effort, not to negate their differences, but to express what they have in common with others.”

France is “indivisible,” according to its constitution, although that implies a different formula for national unity than the American e pluribus unum. The French census doesn’t classify by race or religion because such an acknowledgment of difference would rupture the national myth of a colorblind society of equal, united citizens.

A former member of the Socialist Party, Bouvet is confident and outspoken, and regularly opines on TV news or airs his grievances to his nearly 15,000 Twitter followers. He’s middle-aged and bearded, with shaggy hair. His tone his subdued, almost sleepy, even as he outlines his ideological positions. Bouvet says the “common” is, more than ever, imperiled by attacks against laïcité, or French secularism—the enabling principal of the French national triptych of freedom, equality and fraternity, but also of the free expression that the members of Charlie Hebdo’s staff died for. That after the attack, for example, some Muslim students from working-class or poor suburbs, or “banlieues,” said the magazine “had it coming”—because it went too far in caricaturing the prophet Mohammed—was in itself an assault against laïcité and the common.

With that in mind, the fate of laïcité and its rapport with Islam were central to the afternoon’s panels. The event’s subtitle, “from memory to combat,” was telling—it was difficult to glean anything from the panels beyond a sense of crisis, or an impending war. The speakers leveraged Charlie against a spate of perceived threats they said are clawing at the French social fabric: creeping “communitarism” or multiculturalism; radical Islam converting banlieue youth at a dizzying pace; a segment of the French Left betraying its values to accommodate Islamism in its most dangerous forms; and “alleged feminists” who “support” the “Islamic headscarf”— exclusively described as a symbol of Islamism. One panel, which the movement’s detractors criticized as deepening stigmas about the banlieues, considered how to “be Charlie in Seine-Saint-Dénis,” the poor, majority-Muslim department north of Paris often characterized as a “lost territory” of the Republic.

Laïcité isn’t just about religion

That laundry list might seem at best tangentially related to secularism and, for that matter, to Charlie Hebdo. That’s true to a certain extent. But since the 1980s, laïcité has been extrapolated to cover a larger conversation about diversity, Islam and deepening divisions over what it means to be French. The late Émile Poulat, a historian, sociologist and, until 1954, Catholic priest, contrasts two laïcités. One exists “in the texts”—the 1905 law that separates church and state, guarantees freedom of belief and establishes citizens’ equal footing before the law, regardless of religion or belief. The second lives in “the minds”—the socially and ideologically charged interpretations of those texts. (In French, it rhymes: laïcité dans les textes versus laïcité dans les têtes.) The discord over the meaning of laïcité is confined to the latter, with warring parties claiming to be the truest defenders of the former.

“Some people contend that laïcité is no longer a valid way to manage the ‘common,’” Bouvet explained. “They say that Islam is a religion that is different from others, and so we can’t apply the same rules because it isn’t compatible with our common way, with the way of non-Muslims.”

Statements like these have fueled accusations that the Printemps Républicain is Islamophobic. The movement rejects that charge and the term itself. The audience at Toujours Charlie! cheered when philosopher Raphaël Enthoven lamented that true Republicans were increasingly forced to “live under a scam: the word ‘Islamophobia’”—a concept, many of the movement’s supporters argue, was fabricated by the Muslim Brotherhood and its extreme offshoots to rally French Muslims against the Republic and bolster the appeal of groups like the Islamic State.

It’s worth noting that when a university in Lyon suddenly canceled a scheduled conference on Islamophobia last summer, many accused the Printemps Républicain—along with the far-right National Front and Fdesouche—of being responsible. Bouvet himself had tweeted that the event was “full of Islamist participants under the cover of academia,” although he denied that his movement played a direct role in its cancelation.

The argument is fundamentally between universalism and relativism—and accordingly, whether laïcité should adapt to religion, or religion to laïcité. That question has been at the heart of decades of debates over Islam in France, whether it pertains to the headscarf or pork-free menus in school cafeterias. Often, the accusations are convoluted—the minority that opposed the 2004 law banning ostensible religious signs in public schools, for example, is often labeled “pro-veil,” a term liberally thrown around at Toujours Charlie! In reality, the law’s critics defend the right to wear a headscarf, not the headscarf itself.

Charlie Hebdo and the terrorist attacks that followed raised the stakes. The Printemps Républicain often casts defenders of the so-called American or Anglo-Saxon model of multiculturalism as complicit—explicitly or not—with radical Islam. Manuel Valls, who was prime minister during the attacks and is close to the Printemps Républicain—he was in the audience at Toujours Charlie!—has continuously denounced the “excuse culture” of sociologists who “try to explain jihad.” He refers to the French intellectuals who have tried to explore the root causes of radicalization, particularly since 2015, and often point to socioeconomic discrimination, France’s colonial legacy and involvement in wars in the Middle East. (Just a week after the Nov. 2015 attacks in Paris, then-candidate Emmanuel Macron came under fire for suggesting that France was partly responsible for the rise of jihad; later on the campaign trail, he was barraged by criticism from across the political spectrum, forced to backpedal after calling the colonization of Algeria a “war crime.”)

The Left Against itself

The Printemps Républicain argues that it’s not just a portion of French Muslims who undermine laïcité by refusing to integrate into the “common.” The crowd applauded emphatically when the famed philosopher and feminist Elisabeth Badinter criticized a segment of the left wing that seeks to “destroy laïcité.” That was a tacit reference to the so-called Islamo-leftists—the journalists, intellectuals and politicians who, in calling attention to anti-Muslim sentiment from contemporary discrimination to France’s colonial legacy, give credence to extremist logic, becoming the “useful idiots” of terrorists. Last October, the daily Le Figaro published an article identifying members of the “Islamosphere,” an idea that gained momentum during the debates over the headscarf law in the early 2000s. At the time, the individuals in question were called “Allah’s Leftists.”

Against that backdrop, laïcité, diversity and integration have come to acutely divide the Left. When the author Henda Ayari accused the controversial Islamic scholar Tariq Ramdan of rape in October, the hysteria over Islamo-leftists captured national attention once again. A spat escalated between the left-wing investigative news site Médiapart and Charlie Hebdo after the satirical magazine published a cover cartoon implying that Edwy Plenel, Médiapart’s editor, was fully aware of Ramadan’s actions but had nevertheless remained silent. Although Toujours Charlie! was organized as a commemoration of the attacks, it took place on the heels of that controversy, which was covered by every national newspaper and captivated TV audiences for weeks.

The polemicist Caroline Fourest, a fixture of the debates and a panelist at Toujours Charlie!, said that she had grown accustomed to “explaining the French model to young British and American journalists” who don’t understand the historical underpinnings of French Republicanism and their centrality to contemporary tensions over laïcité and Islam. (When I interviewed her in September, she undoubtedly saw me as part of that naïve, confused crop). But what she finds particularly intolerable, she added, is that members of the French intellectual sphere increasingly question the country’s proud universalism in the name of an “Americanized” vision of identity.

The argument is fundamentally between universalism and relativism—and accordingly, whether laïcité should adapt to religion, or religion to laïcité.

It’s not just the Left that has fallen prey to the “American approach.” Badinter, the philosopher, also singled out Macron. Critics disparaged the president for not giving the traditional presidential address on laïcité on Dec. 9, the anniversary of the 1905 law. And the likes of the Printemps Républicain were already wary of what he had said on the subject: In September, he asserted that laïcité was neither a “state religion” nor a “negation of religions.” In December, after Manuel Valls urged him to “be tough” on laïcité, he countered by promoting a “tempered” debate. During his Dec. 21 meeting with representatives of major religions, he also stressed the need to remain “vigilant” against the “radicalization of laïcité.” And on Jan. 4, he denounced those who defend a “laïque religion”—the idea that secularism has become so dogmatic that it has, paradoxically, become a religion in itself.

The crowd gasped when Badinter recalled those statements. That was somewhat ironic, given that the conference was, at least as advertised, about free expression and the rising religiosity getting in its way. Bouvet, for one, lamented “pressure to remain silent on a certain number of things: about Islam, about Islamism, about gender equality, about the veil.” In a striking parallel to the issues that consumed Americans in the lead-up to the election of Donald Trump, the Printemps Républicain fears an evolving culture of excessive political correctness that, by arbitrarily protecting minorities, both infringes on free speech and ignores the dangerous realities they might pose.

Hysteria in the echo chamber?

For all the talk about threats to laïcité in the public space from schools to hospitals, the concept actually seems most in crisis when confined to a self-reinforcing discursive bubble—on radio and TV talk-shows, in the never-ending drone of think pieces, or at Toujours Charlie!. It is arguably disproportionate that, with every twist and turn, the discussion returns to the national moment of silence the day after the Charlie Hebdo attack, when some several hundred students—across the entire country—refused to say that they, too, were Charlie. How did the teenage rebellion of a fraction of a percentile of students become so influential, from tireless Twitter fights all the way up to education policy?

My research since September challenges the depiction of a laïcité under threat. I have interviewed scores of middle and high-school students—who identify as Muslim and live in the banlieues—and asked hundreds more to respond to questionnaires. The overwhelming majority says laïcité rarely comes up at school apart from occasional tensions over the 2004 law, which dominates their understanding of the concept. Some see the law as an unwarranted restriction with discriminatory undertones, but just as many others consider it insulation from social tensions, or a way to avoid conflict inside the classroom.

Many teachers I’ve spoken to echo that sentiment—yes, there are problems about religious dress or, occasionally, a student invoking religion to contradict a science class. Eating pork in the cafeteria—or fasting during Ramadan—can also be difficult to navigate. But having to deal with such issues is hardly the norm.

Briefly scroll through Twitter, however, and laïcité seems like the most important issue facing France today, particularly in schools. Even if public-opinion polls indicate that French people are most concerned about security and the economy, laïcité, at least as a catchall, manages to creep its way into those seemingly unrelated topics.

The media—mainstream and new—have played a role in fueling hysteria over laïcité. “Social media offer a tool, open to everyone, for immediate expression, and for many, a tool to air their fears, emotions, or feelings,” Nicolas Cadène, of the Observatoire de la Laïcité—a state agency that “assists the government in its actions aiming to respect the principal of laïcité in France”—explained by email. “Mainstream media pick up on what’s ‘buzzing’ on social media—even if that ‘buzz’ is only coming from a few hundred people who aren’t even directly concerned with it.” That’s why, he went on, it seems like laïcité is “systematically in crisis.” The Printemps Républicain routinely clashes with the Observatoire, labeling its vision of laïcité—a freedom, and facilitator of religious coexistence—overly liberal, and Islamo-leftist.

For all the talk about threats to laïcité in the public space from schools to hospitals, the concept actually seems most in crisis when confined to a self-reinforcing discursive bubble.

That inflated depiction of a French value under attack has political implications. “If the media talk about an issue, of course the government can’t keep quiet, and so it has to make statements, which are then picked up by the media. It’s the little snowball that becomes an avalanche,” Patrick Charaudeau, a professor at Paris University 13 who oversaw an exhaustive study on media representations of laïcité, told me by phone. Perhaps that’s why, as teachers and parents hold widespread strikes and protests in Seine-Saint-Dénis and beyond over insufficient resources and crippling disciplinary problems, Education Minister Jean-Michel Blanquer announced two new mechanisms to manage attacks against laïcité in schools, including a “Council of Sages,” of which Bouvet was named a member.

Many analysts point to the first “headscarf affair” in 1989—when three students in Creil, an hour north of Paris, refused to remove their headscarves at school—as an important example of the media hype around laïcité. “The media didn’t provoke the headscarf affair, but they turned it into one,” Charaudeau said. “That a few girls refused to remove their headscarves created drama inside one school, in one city—local newspapers picked up on it, the far right seized it to say that radical Islam was taking over, and suddenly it ascended all the way to the Education Ministry.”

Without the media’s inflation, Charaudeau suggested, perhaps the stage wouldn’t have been set for the 2004 law ultimately banning religious signs in public schools. One study he coordinated indicates that in the time between a similar incident in September 2003 and the fall of 2004—the first back-to-school with the law in place—more than 2,100 dispatches about laïcité and the headscarf were published, constituting over a third of the total number during that period.

The media’s tendency to sensationalize isn’t necessarily politically motivated, of course. “Its ideology is, above all, dramatization,” Charaudeau said. And the issues raised at Toujours Charlie! aren’t fabricated, either. But that dramatization can give contrived urgency to ideological causes. It’s no surprise that reporters and camera crews swarmed the lobby of Folies Bergères, and that every national media outlet covered the event, giving life to the cause.

No winners in a battle of extremes

The Printemps Républicain is often labeled reactionary, the Islamo-leftists naïve. But the enmity has become calcified as each side clings desperately to its own to agenda, muddling the debate and accusing the other of betraying the Left’s ideals. While each side condemns extremist violence, the conversation has become one about French Muslims on a larger scale, glossing over nuance in order to make a point, to win an argument. But by deepening divisions, the debate makes it more difficult to rally the nation around a common cause of reducing conflict and combating extremism.

It’s true of course, as the Printemps Républicain says, that it is unjustifiable to murder a cartoonist for alleged blasphemy—and that’s not the argument that the majority of those labeled Islamo-leftists are necessarily making, either. Rather, they’re insisting on the need to unpack the sentiments of injustice that those highly mediatized several hundred students—perhaps considered the tip of a “grievance iceberg”—expressed back in January 2015. To ask why, when Macron dared to apologize for France’s colonial heritage in Algeria, for example, he was vilified across the political spectrum.

Caroline Fourest is right that some American journalists—she loves to criticize The New York Times—sometimes overlook the historical roots of laïcité and its role in the universal model. But saying that something is uniquely French or historically grounded doesn’t make it immune to evolution, nor does it necessarily justify a dogmatic adherence to a vision of society that erases difference in order to unite.

That seems to be Macron’s position, for now. But with all the background noise, it will be difficult to have the “tempered” conversation about laïcité he so controversially called for in December.