BAMAKO, Mali — On first approach, the Senou displaced persons camp bears all the signs of a settlement inhabited by desperate people fleeing war. The shelters, erected in a grid, are cobbled together from tarp, fragments of wood and morsels of sheet metal. People stand in line with plastic jerry cans to fetch water from a spigot for cooking and cleaning. Most of the residents are elderly, women and children.

At the end of 2022, over 440,000 Malians were displaced by conflict within the country’s borders out of a population of 22 million people. Of those, around 10,000 have sought shelter in this city, the national capital. Senou, which now hosts around 1,500 people, is just one of four official camps in the city recognized by the government.

What differentiates Senou from the others is that it was established and is run primarily by displaced peoples themselves with assistance from ordinary Malian citizens. It is a tragic place, with people who have suffered horrific violence and exile. But speaking with those who established and help run the camp, one can’t help but be moved listening to the stories of middle-class Malians who gave up material comforts and dedicated themselves to helping their fellow countrymen. Tchello Kassé, my friend and interpreter, summed it up perfectly after one of our visits: “These people are the real humanitarians.”

The current war began in 2012, when Saharan Islamist rebels seized Mali’s northern half and declared independence. They were dislodged a year later by a French intervention, but in 2015, a jihadist insurgency emerged from a power vacuum in the center of the country. The government and many Malians directed blame toward the Fulbe ethnic community—only 14 percent of the population and long underrepresented in government—for the increasing jihadist attacks largely because of a large presence of Fulani herders among the militants’ ranks.

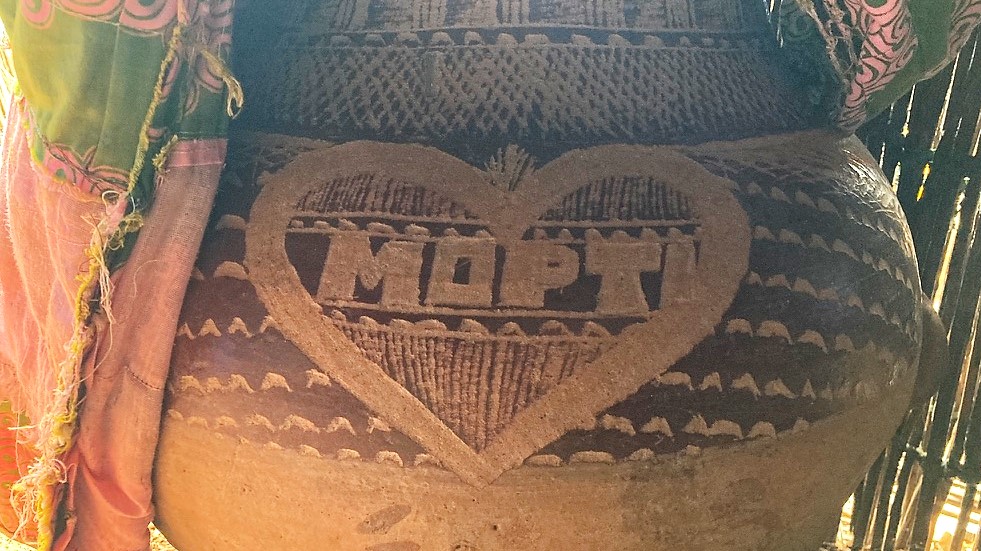

Amid rising insecurity in the central regions of Mopti and Segou, villages formed so-called self-defense groups. While some did protect their communities, others used the war as a pretext to seize prized land from their neighbors, leading to spiraling intercommunal clashes with rising death tolls. The killing escalated sharply in late 2018 and early 2019 in the eastern part of Mopti region, where members of the Dogon ethnic group and nomadic Fulbe herders engaged in decades-long disputes over access to water sources and adjacent lands.

In the early hours of the morning in mid-February 2019, Aminata Barry Sidibe, an elderly Fulbe woman born and raised in the small village of Minima, was admiring her day-old grandchild when she suddenly heard shouting and the crack of gunfire. She grabbed the newborn and her daughter-in-law and ran to a nearby forest. They were soon joined by two of her three teenage children. From the safety of the trees, they watched as their Dogon neighbors set fire to their houses and destroyed the village granary.

Realizing they did not have homes to which to return, they began the six-mile walk to Koulogo, another town on the main road. When they arrived, a little after daybreak, they were directed to a bus carrying other survivors from Minima, waiting to take them to Bamako. Sidibe’s husband and youngest child were nowhere to be seen. Twelve hours later, Sidibe, who had never travelled further than the regional capital of Bankass, stepped off the bus into the heaving jumble of dilapidated shacks that had sprung up in the Faladié cattle market in the middle of a city of 2.5 million people.

Before the war, the market was known as a place seasonal beggars could rent a small parcel of land to erect a shack and be close enough to the city center. Some of the first people who arrived in Bamako following the outbreak of war in 2012 picked up this survival strategy, but there were not enough displaced people to get the government’s attention. That changed when neighbors went to war in central Mali in late 2018.

The first time Kola Cissé heard that people were living in the Faladié cattle market, he did not believe it. “I could not imagine anyone living in a place like that,” he said while we sipped tea outside his two-story family house on the edge of Bamako. At the time, Cissé was in his early 30s, had a college degree, worked at a travel agency and volunteered with PINAL, a Fulbe cultural and development association. Compared to most Malians, he was living a very comfortable life.

On January 2, 2019, he and a handful of other PINAL members visited Faladié to see for themselves. “It was inhuman,” he remembers. “People were living in trash. There was smoke and dust everywhere. Elders were begging for a handful of rice.” Cissé shot a video of the conditions and shared it on social media. Within hours, his inbox was inundated with messages from Malians at home and in the diaspora abroad asking how they could help. A week later, he quit his job at the travel agency and committed himself full-time to helping displaced people in Faladié.

Hadja Diallo, a short woman with a large personality, was among those moved by Cissé’s video. At the time, Diallo, who had recently fled her hometown in central Mali when jihadists executed the mayor and traditional chief, was living with relatives in an upscale neighborhood of Bamako. She did not have any money to contribute, so began donating her time, joining Cissé on his visits to Faladié to help take a survey of people living there. “I wanted to help sudu baba,” she said, using a Fulfulde term describing fealty to family and a wider community.

Diallo was in Faladié the day Sidibe arrived among the busload of people from Minima. They both recalled how one woman was still wearing her charred clothing, and another was running around shouting “Fire! Fire!” despite the absence of any fire in the camp. Diallo introduced herself to Sidibe and the others and helped steer them toward a tent for shelter while she found water and bowls of rice.

By early 2019, busloads of traumatized people fleeing their homes were arriving in Faladié every week. Compelled by the scenes of desperation and the fact that no one was doing anything about it, Diallo, Cissé and others at PINAL threw themselves into helping. To raise awareness, Cissé invited journalists and helped interpret their interviews. The volunteers were also raising funds and coordinating the donation of food and clothes. Over weeks, they got to know the displaced people and convinced their community leaders to form a committee to help distribute aid and make communal decisions.

Not everyone appreciated those actions, however. When Cissé approached various government ministries for help, they punted responsibility to the local authorities. Journalists began publicizing the conditions in Faladié, and officials, embarrassed, tried to restrict access.

Meanwhile, livestock traders were siphoning off food aid while charging people to stay there. Far from home and with no income, young people were becoming involved in crime, drugs and sex work to pay for shelter and water. Over time, basic conditions may have been slightly improving, but sometimes Cissé and the others felt they were expending more energy fighting the system than actually helping those in need.

In February 2019, at the invitation of PINAL, retired General Ismaïla Cissé visited Faladié for the first time. The General, as he is called, is a rare high-ranking Fulbe commander who maintains a stellar reputation in both Fulbe and government circles. That day in Faladié, Diallo and Cissé watched as he walked between the squat makeshift structures, sidestepping piles of refuse to greet elderly people in the rural Fulfulde language of his childhood. At one point, the General got very quiet, and when Cissé turned around, they found him weeping silently into his hands.

After the visit, he asked what he could do to help. As Cissé launched into a description of difficulties, the General interrupted: “I live on a large piece of land in Senou, why don’t people move there?”

A few days later, Cissé, Diallo and a handful of other PINAL member drove 30 minutes outside the city center on the progressively rutted roads that lead to the Senou neighborhood. Apart from the General’s modest compound, the five acres he was offering were uneven and covered in brambles, with just one spigot he used to water his cattle.

“There was nothing there,” Diallo recalled. That cut both ways. On one hand, they would have to build all basic infrastructure themselves. On the other, they would not have to deal with difficult local authorities to do so.

However, many of the displaced were reluctant to resettle in Senou. Having found basic stability in Faladié after watching their homes burn, they did not want to embark on another uncertain move. And when the owners of the cattle market heard about the plan, they spread rumors and advised people not to move, concerned they would lose income. Adding to the confusion, the government suddenly announced it would open a new camp for displaced people at a nearby school.

By that point, Diallo had built strong relationships with people in Faladié, most of whom, like her, were women without their husbands. She decided the best way to show them moving to Senou would improve their lives was to join them in the resettlement. She nonchalantly brushes off her willingness to forfeit the comfort of her relative’s house to move into a displaced persons camp. But her actions convinced Sidibe and other Minima families to trust PINAL and move to Senou.

On March 25, 2019, a convoy of buses brought the first families, all from Minima, from Faladié to Senou. While Diallo had been convincing people to move, others were organizing the leveling of the General’s land and construction of basic shelters, all funded by contributions from Malians at home and in the diaspora. The first few days were difficult as people got used to their new lodgings and developed basic routines for fetching water, cooking and cleaning the camp.

One of the first things the new residents did, with the support of Cissé and others at PINAL, was establish a displaced-persons-run management committee. As people from the same villages usually stayed together, they organized each group to nominate one person, usually someone related to the chief, to serve on the committee. Sidibe and others from Minima nominated Diallo. Today, the committee is still responsible for coordinating decision-making over larger camp issues, serving as a conduit for displaced peoples’ voices, solving disputes between residents and organizing daily tasks.

Over the months, Cissé, the General and the management committee managed to bricole—a French word meaning to assemble with multiple parts—better facilities for camp residents. The one water spigot was expanded into two water towers, installed by the non-governmental organization World Vision, which offers a more regular supply free. The Red Cross helped acquire basic medicines for the camp, while the government appointed medical professionals to see patients on a weekly basis. Doctors Without Borders funded the construction of toilets with cisterns on the edge of camp. With help from a GoFundMe crowdsourcing campaign, they remodeled an existing building to serve as a school.

Those basic infrastructure projects had a massive effect on day-to-day lives. The orderly and transparent distribution of food aid meant Sidibe did not feel she was competing with fellow displaced people and could start to build better relationships with neighbors. Free shelter and water meant she could use the little money she comes across to supplement her diet. Confident their mother was in a secure environment, her two sons were able to travel just outside Bamako to find work herding cattle. “Thank god we moved here,” Sidibe said, “I don’t know how we would be living still in Faladié.”

It took about a year for the basic infrastructure to be installed and the camp to reach its current population of around 1,500 people. It was around that time Sidibe’s husband suddenly appeared, having spent a year sheltering with relatives in Burkina Faso. While relieved he was alive, she was pained he did not speak much, was moodier and rarely left their corner of the camp.

Cissé, who had gone without a salary for a year, had to start looking for a job. He was eventually hired by the Red Cross. Meanwhile, Diallo, a pillar of the camp, lives in Senou to this day, where she has adopted orphans. The General still resides in his house by the camp’s school, deeply involved in decision-making.

Everyone I spoke to during my visits said although they prefer Senou to Faladié, they still face significant challenges. Residents lack all the medications they need, particularly in the rainy season when mosquito-transmitted diseases are more common. There are no paid jobs in the camp, which is far from town, so ahandful of younger residents pass the time sitting around. Disputes occur between residents of the camp and their neighbors over who can take firewood from a nearby patch of trees. And while most basic needs are provided, a number of people, such as Sidibe’s husband, remain traumatized and require advanced care.

Senou’s residents manage the day-to-day affairs of the camp, but they are all still completely dependent on outside aid and donor funding cycles. “If you go and ask for help, it runs out quickly,” the General explained. “Constantly asking for help becomes exhausting.” Furthermore, he said, there has been even less aid available since the Malian government banned all French state-funded NGOs in November after France announced the freezing of development aid. “Medicine is more expensive and difficult to acquire and now we have to send more people the public hospital,” he said, pausing for a minute, “Not that there’s any more medicine there.”

There is a strong sense at Senou that displaced people of Fulbe ethnicity are particularly ignored by the government. Meanwhile the Malian government not only denies discrimination on ethnic grounds but also claims credit for Senou’s relative successes. My first visit to the camp last September was interrupted by a government employee who politely forbade us from speaking with camp residents without ministerial permission. In the meantime she offered to answer all my questions. She said the government ran the management committee and had built everything from toilets to the school and provided all the food and water.

When I returned a few days later (with the General’s blessing), residents rolled their eyes at that characterization of events. While careful not to speak ill of the current authorities, the General said the government often re-brands outside aid as coming from itself. In the last year, the authorities have also become suspicious of private donors to the camp and are trying to channel all donations through government ministries. A member of the camp’s management committee who asked to remain unnamed told me officials show up for publicity, but leave when no one is paying attention.

The underlying tension manifested itself most recently with the teacher assigned to the school. After turning a dilapidated shack into a series of schoolrooms with funds raised on GoFundMe, Cissé and the General appealed to the Education Ministry to incorporate the school into the public system. The ministry agreed but after making a big deal about opening a public school in a displaced persons camp, it sent teachers who do not speak Fulfulde, and therefore can’t communicate with the students. Further appeals by the management committee and the General for a teacher who can speak Fulfulde have been met with silence.

Despite the challenges, it is clear the residents of Senou are grateful to Cissé, Diallo, the General and dozens of others not mentioned here. During my visits, elderly women jokingly referred to Cissé as their husband. Sidibe burst into spontaneous praise for Diallo more than once, who characteristically shrugged it off each time. A few babies born in the camp have been named after the General.

Yet while Senou has been a sanctuary from the violence tearing the country apart, most in the camp said they would go home the moment it is safe. “I would rather grow my own food than be given it by a stranger,” Sidibe told me. “One day, god willing, I will be able to invite Hadja [Diallo] to Minima and share fresh cow’s milk and millet cereal with her.”

Top photo: One of the many NGO signs that dot the settlement