I presented a version of this paper in February at “Framing War and Conflict in Comics,” the second annual Symposium on Arab Comics at the American University of Beirut.

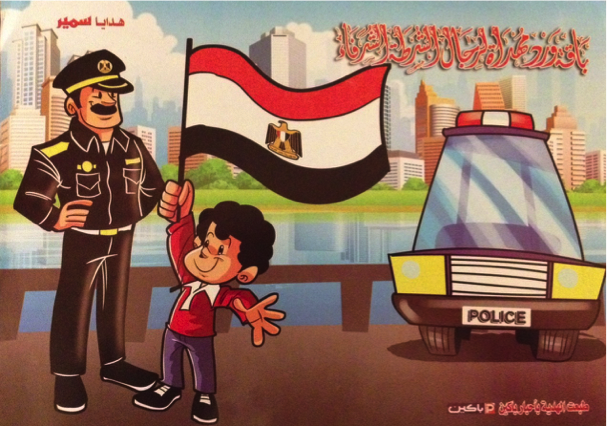

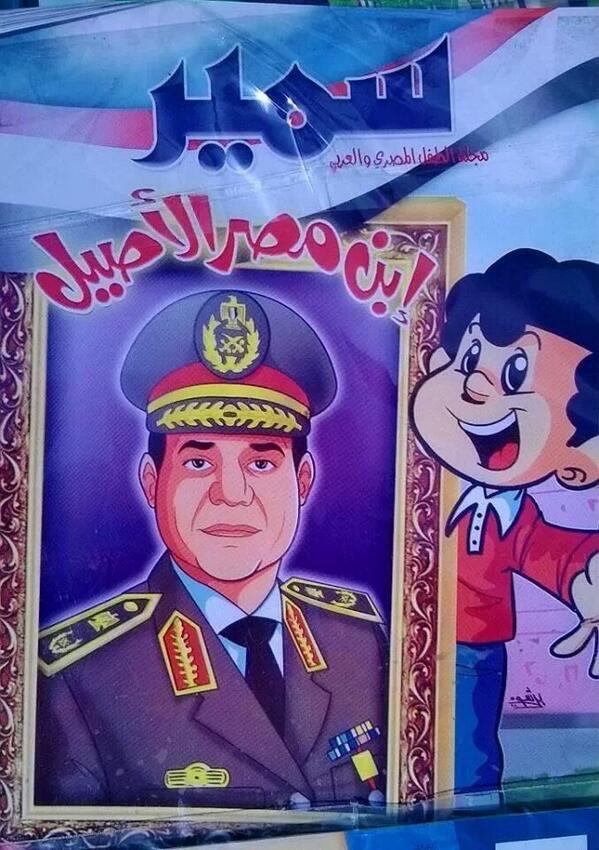

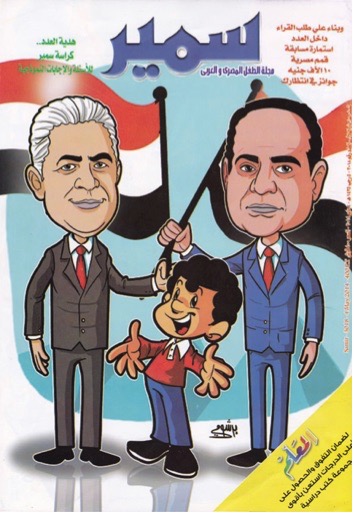

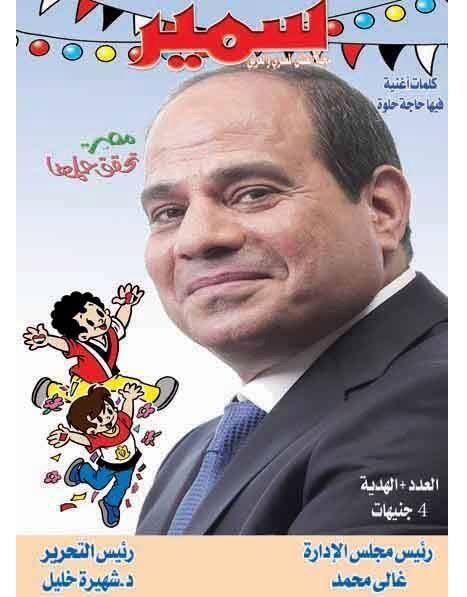

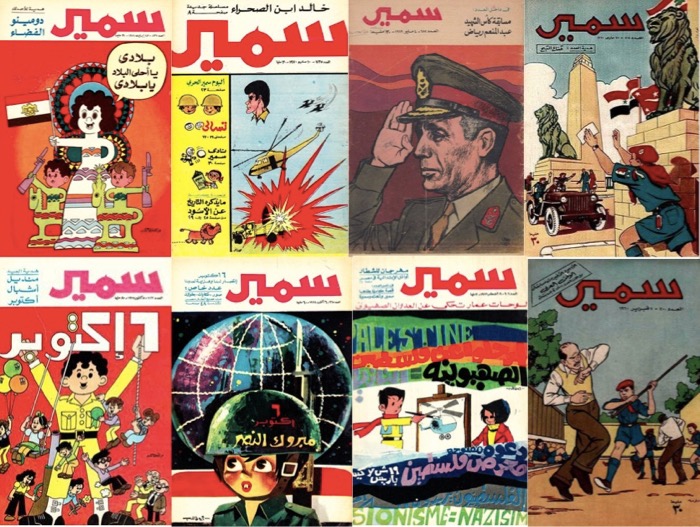

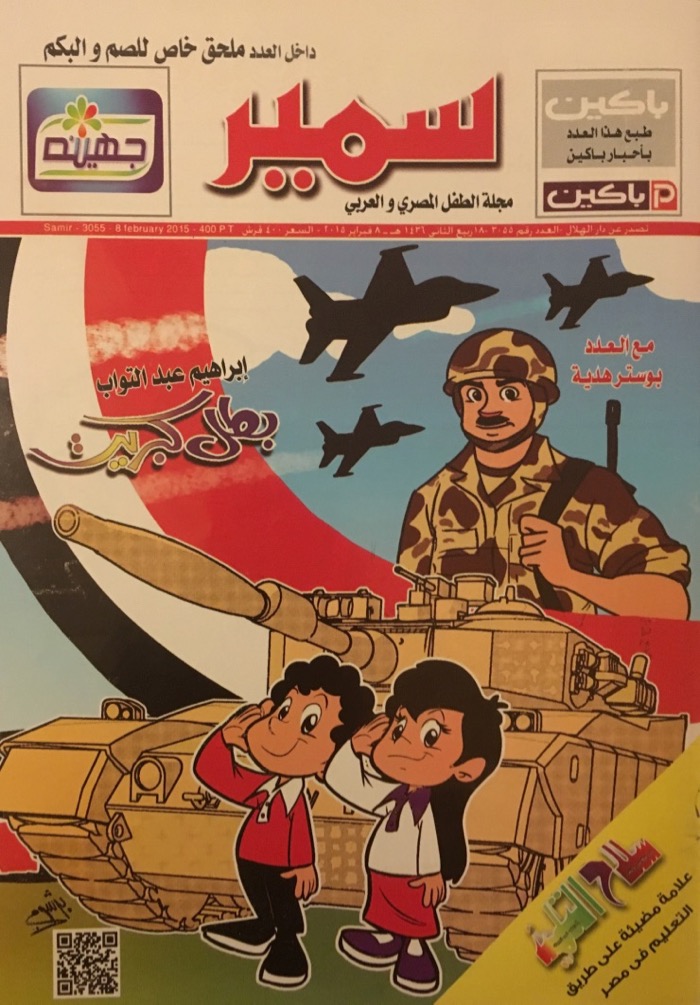

When General Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi ran for the Egyptian presidency in the spring of 2014, the children’s magazine Samir published a stoic caricature of him its cover. This wasn’t the first time that Sisi, who had overthrown the country’s first democratically elected president a year prior, had appeared on the cover of the kids magazine. A couple of months earlier the curly-haired boy Samir, the magazine’s signature character and namesake, held a gilded framed portrait of a uniformed Sisi with the headline, “Egypt’s authentic son.”

“We had a very big problem when we had published that caricature,” Shahira Khalil, the chief editor of Samir tells me at her office at the state publishing house Dar Al-Hilal, in a grand, century-old building. “Some people, they told us, ‘You are politicizing children.’” Liberal parents were angry that the magazine was glorifying the junta leader. The “radical Muslims,” as Khalil calls the ousted and now illegal Muslim Brotherhood, were likewise upset that the leader who oversaw a massacre was being lionized. Even the mainstream media, which was categorically pro-Sisi, was not sure what to make of the cover at a time when caricatures of the former general were rare.

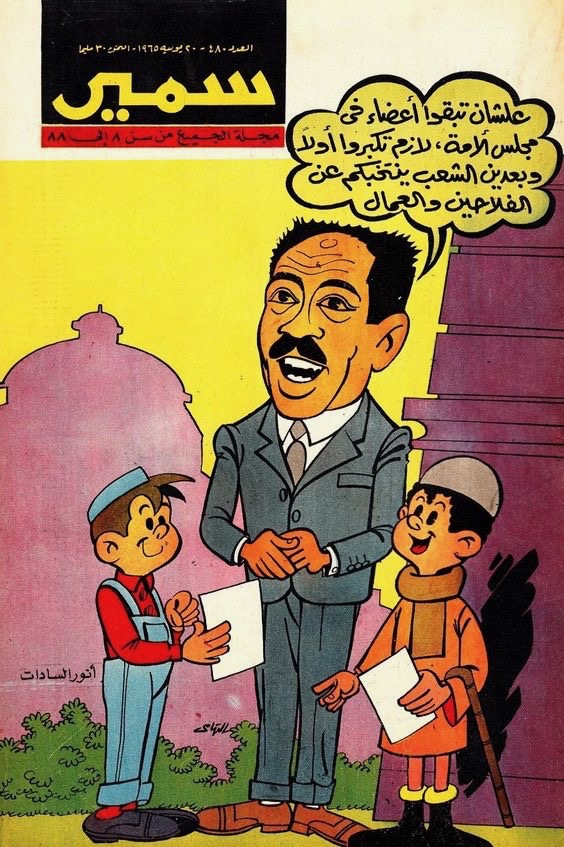

Khalil, who wrote her dissertation about the children’s press in Egypt, knows well that politics has always been integral to Samir throughout its sixty-year history. “We are a purely Egyptian magazine,” she says, noting that Presidents Gamal Abdul Nasser and Anwar Sadat regularly graced its cover as cartoon characters. Indeed the portraits of Sisi approximated the style of Samir’s old school covers, which ran the gambit of Egyptian folks heroes, including famous authors, actors, athletes, musicians, and military men. Khalil, who previously worked as managing editor of the Arabic edition of Mickey (Mouse, that is, the Disney publication), makes a point of distinguishing between patriotism and politics. “We should present patriotism, by the way, all of the time,” she says. “The politics is somewhat difficult.” That Khalil attempts to extract patriotism from politics shows the complexity of a society reeling from a coup and revolution.

Of course, it is impossible to distinguish between politics and patriotism. The characters who are valorized, the historical events that are commemorated, the holidays that are celebrated, the symbols that are rendered—each of these represents a political choice. By saying that the magazine is patriotic, Khalil obscures the fraught politics of deciding who is a hero and who is a villain. The covers and strips of Samir attempt to provide a holistic, straightforward, and positive view of patriotism in Egypt, inadvertently revealing the publication’s deep-seated politicization.

***

The funny thing about Egyptian children’s comics is that, in spite of their political import and ubiquity, they often evade scrutiny because of their sheer playfulness and relative innocuousness.

Perhaps the first scholar to critically analyze the colonial dynamics of European children’s comics is the theorist Frantz Fanon. He considers their political power in his 1967 book Black Skin, White Masks:

The Tarzan stories, the sagas of twelve-year-old explorers, the adventures of Mickey Mouse, and all those “comic books” serve actually as a release for collective aggression. The magazines are put together by white men for little white men.[1]

He goes on to discuss how “local children,” that is youngsters outside of the metropole, consume European comics. He argues that comics malign whole races: “In the magazines the Wolf, the Devil, the Evil Spirit, the Bad Man, the Savage are always symbolized by Negroes or Indians.” Hergé’s Tin Tin, for instance, is one well-known example of how Africans or Arabs are stereotyped and vilified in opposition to the white, European hero. The comic book subtly indoctrinates children to esteem one race over another, and one worldview over another.

To overturn the self-hate perpetuated by European children’s comics, Fanon proposed that alternative publications be created for youngsters. “I should like nothing more nor less than the establishment of children’s magazines especially for Negroes,” he wrote. When Fanon wrote this in the late 60s, the business of Arab children’s comics was already wildly successful. The magazine Samir at the time had a circulation of around 80,000, with distribution throughout the Arab region.

Fanon’s inquiry my starting point for a new study of children’s comics. If European children’s magazines “served as a release for collective aggression,” a manifestation of discrimination and violence against out-groups, what then of the Arab comics produced for distinctively Arab audiences? In contemporary issues of Samir, what kind of little Arab men are being constructed?

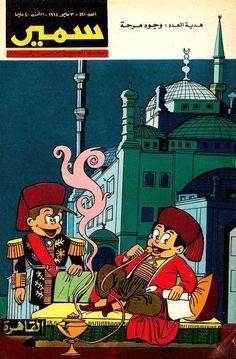

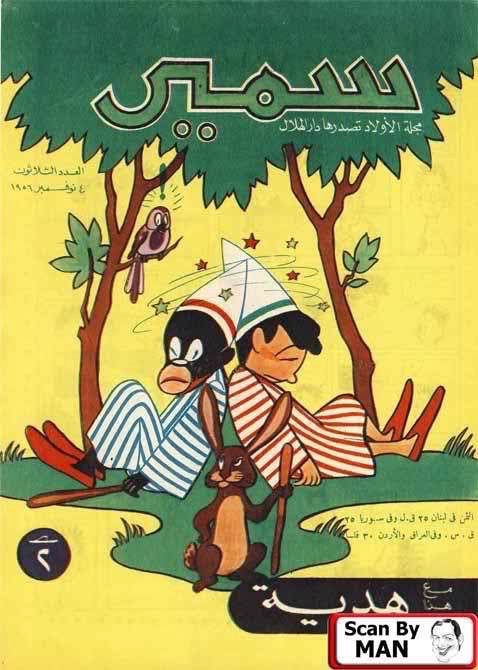

Before considering these questions, let us first glance at the history of Samir, Arab children’s comics more broadly, and the limited scholarship about them. Beginning in the 1920’s and only growing in popularity, Egypt’s first children’s magazines were cut from a European cloth, mostly featuring translations of Western heroes or pastiche that verges on plagiarism. By the 1940s a handful of children’s publications, like Ali Baba and Al-Mustaqbal (The Future), and later Sindibad and Al-Karwan (The Crown), mixed traditional Arab storytelling with translations of famous European comic characters and other typical magazine features. In 1956, Samir is born. Published by Dar El-Hilal, the oldest state-run and sponsored publishing house, Samir synthesized everything that happened in children’s comics over the decades before and in turn creates a bright, fun, outrageous, and beautifully-designed product with a distinctively Egyptian personality.

It is no coincidence that Arabic comics for children gain traction in the 1950s, when Egypt’s Free Officers Movement and Nasser’s new vision of pan-Arabism takes hold. Call it propaganda or education, children’s comics are “an effective tool of indoctrination,” the artist George Khoury JAD has noted. [2] As modern Egyptian identity was being constructed, the narratives of good boys and approved cultural moors reinforced the outline of the idealized Arab young man. And leaders are well aware of what it means to speak directly to young audiences. “We need to reach out to our kids,” Sisi said in an unusual phone-in to a TV network in January 2016, hyping a new children’s magazine published by Al-Azhar, the flagship Sunni institution based in Cairo.[3]

In spite of their political influence, Arabic children’s comics are understudied. Local scholars have scarcely addressed them, perhaps because of their stature as silly periodicals or else it might because of their absence in academic and national archives.[4] Fanon even notes that most people have “not given much thought to the role of such magazines,” a trend that endures to this day and that I hope to remedy through this project. It is worth noting a few exceptions. The 1994 book Arab Comic Strips by Fedwa Malti-Douglas and Allen Douglas explores the localization of Mickey Mouse, bio-comics of presidents, and how cartoonists sneak radicalism into this medium. Furthermore, in a recent presentation, Lina Ghaibeh, director of the Arab Comics Initiative at the American University of Beirut, writes about propaganda in Arab children’s comics. Drawing upon the university’s growing archive, she has surveyed comics published by the patriarchal regimes of Nasser, Qaddafi, and Saddam, among others. She focuses on the techniques of teaching history and nationalism through comics, emphasizing that it is not wholly surprising these self-serving leaders would commission comics of themselves.[5] In another report, Ghaibeh writes, “With the uprisings came the collapse of state propaganda and pan-Arab nationalism, and the emergence of a focus on local issues and problems.”[6] Six years after the revolutions in the region, children’s comics have returned, perhaps more powerful than ever.

Though Samir’s circulation today has dipped to around 6,000 weekly, it remains a bellwether of the political mainstream, a snapshot of Egyptian educators’ worldview and a baseline of the next generation’s beliefs.

***

Egyptian comics invariably grapple with the very problems that European comics did. The tendency to assign heroes and villains based on prejudice is on nearly every page within the miscellany of stories.

Samir replicates the same power dynamics—the very collective aggression—that their Western predecessors did, by creating new villains in the old mold. Fifty years ago, cartoonists in Egypt were mobilized in the war effort against Israel and drew covers and strips in support of the cause. A series of strips called “Samir in Tel Aviv,” from 1967, depicts the young hero sneaking across enemy lines to battle Israeli tanks and acquire sensitive intelligence for Egypt. But Israelis are not the only enemies. A few pages away from these comics of Arab resistance, one finds imagery that reinforces Western hegemony, neo-colonialism, and Orientalism.

Samir frequently copies Tin Tin, Tarzan-like characters, and other colonial heroes. The starkest examples of this are characters in blackface who appear in early editions of Samir as well as in some recent editions. This is unabashed racism and bigotry, translated to Arabic. In its project to create a distinctively Egyptian magazine, Samir reproduces of colonial power relations. Using racist images, Egyptian and Arab identities are constructed in opposition to blackness or African identity. I was surprised to see a boy named “Sambo” in the table of contents of a 2016 issue of Samir, an indication that these racist characters persist to this day.

As new villains and old bigoted caricatures appear within the same issue, Fanon’s point bears repeating: “comic books serve actually as a release for collective aggression.”

When directed at outsiders—those of a different nationality or those of a different race—aggression becomes the basis of a new identity. While Fanon focused on the perverse identification of local children of color with white heroes, his wider point pertains to how children are indoctrinated through comics. The creation of heroes demands the perpetual vilification of the Other.

***

Yet for all of the nationalism and propaganda that exists in Samir, there is another conflict underway within the artists themselves. Independent artists have a habit of rendering furtively subversive stories within the pages of nationalistic magazines.[7] Harmless and breezy, comics serve as a liminal space where sometimes artists can take incredible risks without anybody noticing it.

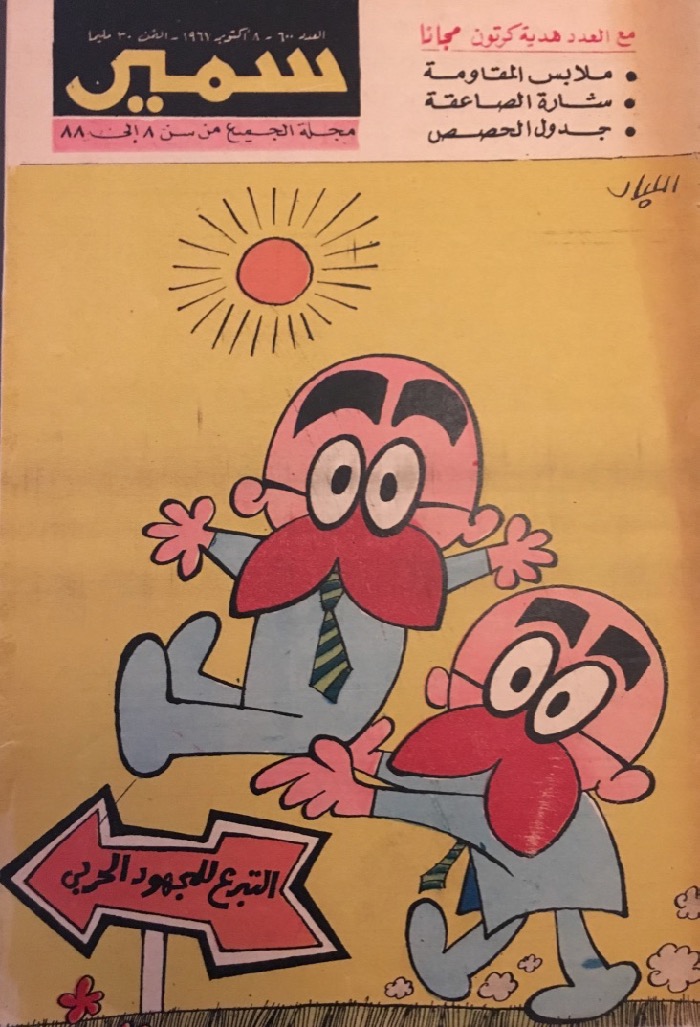

A cartoonist might superficially support a policy in a strip but the deeper meaning can suggest the exact opposite. Two full-page comics from 1967 issues of Samir capture this tension. The artist is Mohie Eldin El-Labbad (1940-2010), a skilled comic artist, astute chronicler of the art form, and an illustrator of great breadth.[8] Labbad’s famous character is the ginger-mustachioed Zaghloul Effendi, a gentle-mannered mischief-maker who means well—or does he? For the cover of an October 1967 issue of Samir, Zaghloul carries his double—either a twin or a brother—on a sunny day. The sign below reads, “Donation to the War Effort.” On the surface, Zaghloul is supporting the state by making a generous donation. But isn’t it somewhat subversive—perhaps even dismissive of official policies— to donate one’s brother? If Zaghloul wants to be rid of his annoying brother by sending him away, then this act is perhaps as selfish as it is generous.

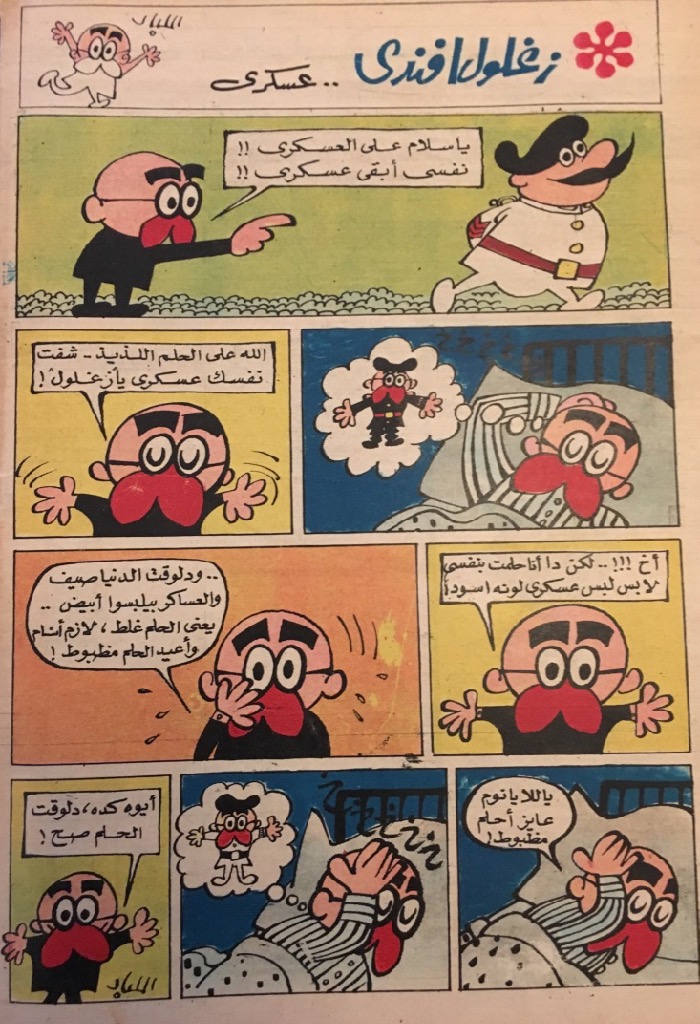

The back cover similar suggests such a double-movement of altruism and critique. In the full-page “Zaghloul Effendi is Very Generous,” the character turns up to the donation office with a large sack of household items for the soldiers. He proclaims to the clerk that he is donating everything he owns, checking off the items. By the last panel, Zaghloul strips—removing his clothes and even his spectacles—and runs off. The bureaucrat at the war office chases after him. “It’s not reasonable, Zaghloul Effendi,” he screams. “It’s not reasonable that you go in the street like that, it’s not…” He has literally donated the clothes off his own back. This generosity or selflessness can also be read as a critique of how the state subsumes the individual’s interests. The cartoonist seems to argue that the state demands everything of its children. If Zaghloul Effendi is very generous, then the state is very meager and stingy indeed.

Cracking jokes about authority in the face of war is tantamount to criticizing authority. There are many examples of the jocular Zaghloul poking fun at military officers and policemen, published in the wake of 67. In one strip, Zaghloul crashes his little sedan into a police van, and a dozen white-uniformed officers pop out to write him tickets. For the critical reader, the punch line is about the redundancy of policing and officers’ eagerness to punish.

Labbad himself had a complicated relationship with the state. He “disagreed with Nasser’s policies most of the time, had huge concerns about the lack of freedom,” according to the contemporary cartoonist Andeel, who relays a thorny story of Labbad’s political outlook. One day, when Labbad and some friends were crossing the street in the Cairo district of Heliopolis, they were forced to stand on the corner and wait for an hour or more. Nasser’s procession was coming from the airport, and the neighborhood was on lockdown. The sun was glaring. Labbad was irritable that “fake populism and mob mentality,” was forcing him to be late. That was “until Nasser’s car drove by and the president tilted his head and looked him in the eye and waved at him. ‘I found myself unintentionally jumping like crazy and screaming at him like a child: Nasser! Nasser!’” said Labbad.[9] The cartoonist was a critic but also susceptible to the cultish following and populist personality of Nasser, like any of us might be.

In the context of today’s comic production for children, a similar power dynamic exists. The contemporary cartoonist Tawfik often publishes oppositional political cartoons on social media and internet platforms. He has audaciously cartooned the deaths of demonstrators, mass death-sentencing, and other injustices. But he also draws lively narratives for Samir and other children’s rags.

For the online news portal Masr Al-Arabiya, Tawfik drew a cartoon, entitled “Agendas” in January 2015. It is a calendar, with the page of January 25 (the date the 2011 revolution began) ripped out. The torn calendar is an indictment of counterrevolutionary forces that have taken over the countries. The cartoon also conflicts with the message of Samir’s January 2015 issue, which offered a potpourri of pro-military messaging. While contributing to Samir, Tawfik continues to publish anti-army illustrations that go against the grain of the mainstream media.[10] Artists like Tawfik represent the possibility of subversion and radicalism within the establishment pages of Samir. In our conversation, Shahira Khalil, the editor of the magazine, called Tawfik one of the greatest cartoonists in the country and praised his political cartooning. I wondered if she had seen some of more rambunctious critiques of the government. Amid the July 2013, Tawfik drew a large bloodied wolf in a military uniform, smiling, hovering over a group of protesters.[11] At a moment of intense euphoria for military action against the Muslim Brotherhood, Tawfik drew attention to the military’s use of violence with impunity. Needless to say, that is a narrative that is absent from Samir.

Looking at Samir from 1956 or 1967 through today, a glossy history of Egypt is on display. “Samir expresses and reflects our society,” says Khalil, “with all of our occasions, political or patriotic or religious. The 2011 revolution is there, everything is in there… from the viewpoint of children.” But adults, necessarily, construct the viewpoints that children consume, choosing carefully what to include and exclude. They compose straightforward narratives of the 2011 revolution, for example, or the election of Sisi, which in turn conceal a society in conflict, an Egypt at war with itself. The final product, brightly illustrated and slickly produced, provides legible narratives of nationalism. Underneath, however, looms something darker, intractable conflicts that defy the neat frames of children’s comics.

[1] Frantz Fanon. Black Skin, White Masks, New York: Grove Press, 1967.

[2] Building from Jad’s comments at a number of conferences since 2015, I began to consider this idea in a recent essay. See “On the Arab Page,” Le Monde Diplomatique, January 2017. http://mondediplo.com/2017/01/15cartoons

[3] Following Sisi’s pledge to assure funds for the publication, Nour magazine said that it had received no additional funding. See: “No Support for Nour Children’s Magazine from Long Live Egypt: Cartoonist,” Egypt Independent, March 19, 2016. http://www.egyptindependent.com/news/no-support-nour-children-s-magazine-long-live-egypt-cartoonist “In Rare Phone-In, Sisi Promises Support for Children’s Magazine,” Egypt Independent, January 23, 2016. http://www.egyptindependent.com/news/rare-phone-sisi-promises-support-children-s-magazine

[4] Finding midcentury children publications can be very difficult because, as an ephemeral publication for youngsters, Samir is not properly archived. Back issues are often combined, re-bound, and sold cheaply for poor children to read older print runs; I sometimes come across a random selection at newsstands. Last month, in fact, I bought 40 issues from 1965 and 1967 at a stall in the used book market, fodder for future research.

[5] Lina Ghaibeh. “Propaganda in Comics in the Arab World,” The Media and Digital Literacy Academy of Beirut, August 22, 2014.

[6] Ghaibeh. “Telling Graphic Stories of the Region: Arabic Comics after the Revolution,” IEMed Mediterranean Yearbook, 2015. http://www.iemed.org/observatori/arees-danalisi/arxius-adjunts/anuari/med.2015/IEMed%20Yearbook%202015_Panorama_ComicsAfterRevolution_LinaGhaibeh.pdf

[7] In Arab Comic Strips, Douglas and Malti-Douglas describe how the Egyptian cartoonist Hejazi performed such a double game from the 70s through the 90s.

[8] Since his passing, Labbad has continued to inspire the new wave of cartoonists in Cairo: the first issue of Egypt’s pioneering alt-comix zine Tok Tok (2011) was dedicated to him; the first edition of the CairoComix festival (2015) featured his character Zaghloul Effendi in its posters and also presented a gallery of his works.

[9]Andeel. “Mostafa Hussein and Mentioning the Sins of the Deceased,” Mada Masr, July 18, 2014. http://www.madamasr.com/en/2014/07/18/feature/culture/mostafa-hussein-and-mentioning-the-sins-of-the-deceased/

[10] I began to sketch out these ideas in a blog post two years ago, where I first translated this cartoon by Tawfik. See: “Nationalism for Kids,” Oum Cartoon, February 3, 2015. http://oumcartoon.tumblr.com/post/110033484286/nationalism-for-kids-the-egyptian-childrens

[11] I originally wrote about this at the time. See: “Egypt’s Fault Lines, and It’s Cartoons,” the New Yorker, 9 June 2013. http://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/egypts-fault-lines-and-its-cartoons