As campus events go, it is difficult to imagine anything less controversial than the “Peace Fair” held at Côte d’Ivoire’s largest university one Friday morning last July. Part of a U.S. State Department-backed program intended to temper a politically volatile campus climate, the fair featured Ivoirian artists and singers, a blood-donation stand and booths where students could learn about famous peacemakers such as Mother Theresa.

So the organizers were understandably surprised when the fair, held in the parking lot of an amphitheater on the campus in Abidjan’s well-to-do Cocody district, came under attack by an agitated mob. Out of nowhere, dozens of men descended on the booths, breaking signs, stealing phones and computers and clashing with police, who responded with tear gas. The U.S. Embassy’s cultural attaché was among those forced to hide inside the amphitheater while students threw rocks at the windows.

The mob comprised members of the Fédération estudiantine et scolaire de Côte d’Ivoire, the university’s largest student movement, known throughout the country by its acronym, FESCI. Though its target was unexpected, the raid itself was of a piece with FESCI’s violent past. Born during the advent of multiparty politics in Côte d’Ivoire in 1990, FESCI became a central player in the two decades of political crisis that followed. Over the same period, the group became increasingly militant, with some members going as far as killing or raping fellow students.

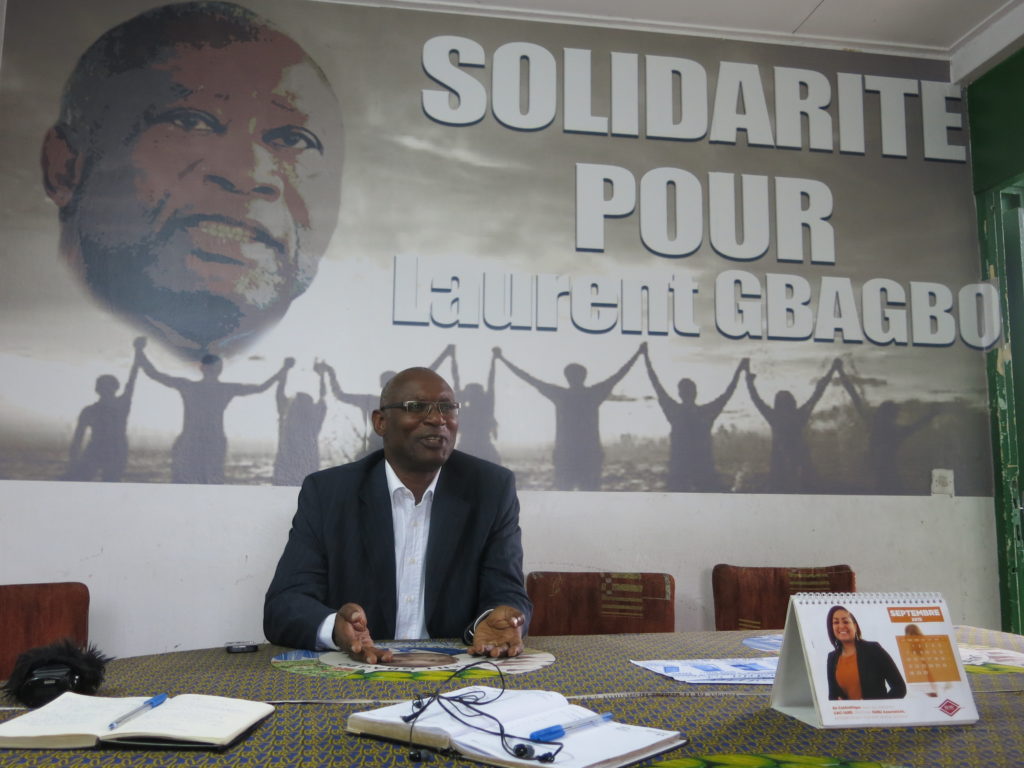

FESCI also served as a proving ground for many of Côte d’Ivoire’s future political leaders. One former FESCI secretary-general, Guillaume Soro, led an armed rebellion that split the country in half in 2002. He is now president of the National Assembly and second-in-line to the presidency. Another, Charles Blé Goudé, served as youth minister under ex-President Laurent Gbagbo and is, like Gbagbo, incarcerated in The Hague awaiting trial for alleged crimes against humanity.

During the height of the violence in Côte d’Ivoire — a five-month conflict that broke out after the disputed 2010 presidential election — FESCI alumni were among the militants who roamed Abidjan attacking perceived supporters of Alassane Ouattara, the current president who defeated Gbagbo in a runoff vote and was initially denied office. Meanwhile, the Soro-led New Forces rebel movement that swept down from the north on behalf of Ouattara, helping thwart the attempt to steal the election, included many young men who had cut their teeth on FESCI-organized sit-ins and strikes during their university days.

This month, Ouattara’s government is gearing up for another presidential vote intended to show the world that Côte d’Ivoire has turned the page on the conflict. FESCI is also claiming to have renounced violence and embraced peace. “We have succeeded in adopting a new behavior,” said Fulgence Assi, FESCI’s current secretary-general. “We have decided to eliminate all actions that are violent in our work.”

But after two decades of operating more like a militia than a student group, FESCI is struggling to convince other students that its reforms will be genuine and lasting. Skirmishes such as the raid on the Peace Fair in July have only reinforced widespread doubts. “I think that FESCI today is behaving like a boy trying to get a girlfriend,” said Aristide Wise Bogny, a leading campus organizer. “FESCI is trying to tell students, ‘You see, now we have really changed.’ But if you say FESCI is not violent, it means that FESCI is no longer FESCI.”

The movement takes shape

Until 1990, the Abidjan campus of the University of Côte d’Ivoire was dominated by a union that had close ties to Félix Houphouët-Boigny’s ruling Democratic Party of Côte d’Ivoire, or PDCI. (Houphouët-Boigny, the country’s founding president, governed Côte d’Ivoire for more than three decades until his death in 1993; the Abidjan campus is now named after him.) When students would complain about problems such as power cuts, the PDCI-linked union simply denied these problems existed and hired street thugs to beat up the most vocal agitators, according to Yacouba Traoré, a former FESCI member and an expert on Ivoirian student organizing.

In March 1990, though, students defied the union en masse and refused to sit for an exam, saying a power cut the night before had prevented them from studying. The incident, Traoré said, highlighted a need for a group that was actually responsive to students’ concerns. FESCI held its first meeting the following month.

Many professors on the Cocody campus — including Gbagbo, who taught history — were leftists who opposed Houphouët-Boigny’s autocratic rule. They supported FESCI wholeheartedly. “For us, we were anti-government at the time, so we liked it,” said Théodore Bouabré, a professor in the English department. “These guys, they were fearless. They had nothing to lose.” Even in the face of a concerted repression campaign by the state, FESCI became the most dominant group on campus within two years.

From the beginning there were hints of the violence that was to come. As part of its crackdown on FESCI, Houphouët-Boigny’s government established a “normalization group” consisting primarily of thugs who were sometimes armed. In June 1991, a group of FESCI members attacked a man named Thierry Zébié, a FESCI defector who had joined the normalization group, stoning him to death in front of a campus residence hall. The killing signaled that FESCI was now in charge and could do what it wanted.

The government banned FESCI in 1991, though this had little effect and its members continued to meet. Upon assuming control of FESCI in 1995, Soro made it his mission to get the organization re-registered, a feat he accomplished despite being arrested multiple times. His battles with the government of Henri Konan Bédié, who succeeded Houphouët-Boigny in 1993, made Soro a household name. In 1997, the year the FESCI ban was lifted, a popular tabloid named Soro, “man of the year.”

While Soro served as FESCI’s secretary-general, Blé Goudé was one of his aides. They both studied African civilization in the English department, reading books by Chinua Achebe and other Anglophone African authors as well as American writers such as Richard Wright. They were even roommates during this period. Koné Boubacar, an English professor who later became chief of protocol under President Gbagbo, taught both young men, and they would sometimes drop by his office. “They were intelligent, but they were not too brilliant as students,” Boubacar said. “It was due to the fact that they didn’t have a lot of time to devote to their studies. Their activities in the union didn’t allow them to be very present in the classroom.”

Their political ambitions were clear to anyone paying attention, Boubacar said. “They both had this ambition to have their say in Ivoirian politics,” he said. “We are not surprised that today they are important political actors.”

However, the events surrounding Soro’s departure from FESCI in 1998 created a rift that ensured the two men would be on opposing sides as Côte d’Ivoire’s political crisis escalated.

The ‘war of machetes’

Back in 1990, the year of FESCI’s founding, Gbagbo’s Ivoirian Popular Front (FPI) party was the first to accuse Ouattara of being a native of Burkina Faso and therefore ineligible to run for president. After Bédié became president in 1993, however, the FPI and Ouattara’s Rally of the Republicans (RDR) party found common cause in trying to undermine the ruling PDCI, which became increasingly weak as Côte d’Ivoire’s economy continued to founder.

This collaboration didn’t last. By 1998, the FPI and RDR were at odds again. To the trained eye, their rivalry played out in that year’s FESCI elections. Soro, the outgoing secretary-general, had picked his No. 2, Karamoko Yayoro, to succeed him. Yayoro had ties to the RDR and would go on to be a youth leader for the party. Blé Goudé, a Gbagbo supporter, decided to run against him, becoming the FPI’s preferred candidate.

By this point, it was clear that Gbagbo saw FESCI — and the university community more broadly — as a necessary ally in his quest for the presidency. “When people say that teachers and university students are supported and manipulated by the FPI, I would like to confirm here once and for all for everyone that it’s an honor for the FPI to support these movements in their fight,” Gbagbo said in a 1997 speech. Blé Goudé defeated Yayoro in the FESCI vote. In an interview several years later, he described this win in clear terms as a victory for Gbagbo at Ouattara’s expense.

Like Soro, Blé Goudé was seen as a threat by Bédié’s government, which had him jailed. So when a military coup toppled Bédié in 1999, Blé Goudé came out in support of Robert Guéï, the new military leader, who in turn gave FESCI control over the university housing stock. But Blé Goudé’s ties to Gbagbo were stronger. When Guéï tried to steal the 2000 election from Gbagbo (Guéï had arranged for Ouattara and Bédié to be barred from running), FESCI helped organize massive street demonstrations that eventually forced Guéï from office.

FESCI demonstrated its loyalty to Gbagbo’s government again in 2002, joining forces with a coalition of youth movements known as the Young Patriots to mobilize in a show of solidarity against Soro’s rebellion in the north. Even before this, FESCI had become increasingly brazen in its assertion of control over all facets of life on campus, collecting rent for university residences and demanding bribes from students and petty traders. After Gbagbo survived the 2002 coup attempt, FESCI members were given even freer rein to do as they wished. Though the public was growing tired of FESCI’s behaviour, Gbagbo’s government clearly saw the students’ support as essential.

FESCI’s pro-FPI character during this period was enhanced by the fact that an intra-FESCI conflict had weeded out many members who might have been inclined to support the RDR. At one point during his tenure as secretary-general, Blé Goudé accused his second-in-command of trying to oust him and align FESCI with Ouattara. The ensuing fighting between the two camps was the most violent period in FESCI’s history, and is known today as the “war of machetes.” According to a report from Human Rights Watch, some students were thrown out of windows while others were hacked with machetes and clubs. At least six were killed and dozens sustained serious injuries.

This “war” was a harbinger of what the country would go through a decade later. “In a loose way,” the Human Rights Watch report notes, “the divisions within FESCI during the ‘war’ took on the regional and ethnic character that has come to characterize the Ivoirian crisis up through the present day, with the FPI drawing its supporters from the largely Christian south and the RDR from the largely Muslim north.” Many of the RDR-aligned “dissidents” ultimately left FESCI and moved out of Abidjan. A “large number” of them would join the New Forces rebel movement, according to Human Rights Watch.

Though the 2002 coup attempt and partition of the country showcased Gbagbo’s weaknesses and legitimacy problem — he himself described the circumstances of his 2000 election as “calamitous” — the former history professor managed to stay in office for eight more years. During that time, FESCI’s turn toward militancy became more pronounced. Students perceived to be sympathetic to the rebellion in the north were targeted for beatings and sexual assault and sometimes killed. FESCI on occasion worked directly with security forces in carrying out rights abuses. Their victims also expanded. No longer content with terrorizing students, FESCI now also targeted professors, journalists, human rights activists and government officials. In one notorious incident, FESCI assaulted magistrates at Abidjan’s Palais de Justice. The fact that no one was ever charged over an attack on law enforcement officials demonstrated to many Ivoirians that FESCI operated with absolute impunity.

Toward the end of the decade, FESCI began pledging to change its ways. “Objectively, it’s true that there have been violence and other problems,” Augustin Mian told Human Rights Watch after he was elected secretary-general in December 2007. “However, it’s not with a magic wand that I can get rid of eighteen years of bad habits. The international community needs to help us. I want a new, mature FESCI that turns its back on violence.”

Many people believe Mian genuinely wanted FESCI to reform. But the evolution of Côte d’Ivoire’s political turmoil made that impossible. In 2010, the country finally held a long-delayed presidential election that pitted Gbagbo against Ouattara and Bédié. During the campaign, Gbagbo adopted a slogan that had previously been used by a candidate in a FESCI election: On gagne ou on gagne — we win or we win. In the first round, Bédié came in third, then told his supporters to back Ouattara in the runoff, handing him the victory. Gbagbo, however, refused to admit defeat, dismissing the vote as rigged.

As Gbagbo led the country down a path toward armed conflict that eventually claimed more than 3,000 lives, it became clear that FESCI alumni would play a critical role in the fighting. One incident was especially foreboding. During a press conference at the electoral commission, a Gbagbo supporter and commission member reached over and tore the results sheets from the hands of the spokesman trying to read them out on national television. “These results are false!” the man shouted, denouncing an “electoral hold-up.” That man was Damana Pickass, a prominent FESCI leader in the 1990s.

FESCI after ‘la crise’

After five months of fighting, Côte d’Ivoire’s post-election conflict ended on April 11, 2011, when pro-Ouattara forces — backed by French and U.N. troops — captured Gbagbo in the bunker where he’d been hiding out with his wife.

The Abidjan campus, however, would remain closed for another year and a half. “The university had become a place for violence and corruption rather than for the broadening and transmission of knowledge. Facing such a situation, the government decided to close the public universities in order to have a fresh start,” Ouattara said during a re-opening ceremony in September 2012. The president added that infrastructure improvements such as new or refurbished residence halls, amphitheaters and sports facilities were “proof that we are committed to having a university of high quality.”

The state of the campus today, though, remains a source of frustration for students, who number more than 60,000. A shortage of classrooms makes it impossible for some professors to complete their courses on time. Students in the hard sciences lack materials for lab work. Internet access is limited to central administration buildings. During the recent pre-exam reading period, the main library was closed, inexplicably, for “vacation.” Books in a second library were stored in a backroom that was off-limits to students, who had to submit search requests with library staff. Many of the books were in cardboard boxes, making individual titles nearly impossible to find.

During the run-up to the Oct. 25 presidential vote, FESCI is keeping a low profile, wary of being branded as troublemakers and agents of the pro-Gbagbo opposition. A changed landscape on campus means the group is also competing today with a handful of other, newer student unions, many of them led by young men who came up through the FESCI system and embrace similar tactics.

But FESCI leaders are still organizing around certain causes, trying to convince students that the group can be an effective advocate for their needs. On a recent Thursday, FESCI called for a protest outside the Ecole Normale Supérieure, a teacher training school. The aim was to help students who had missed a registration deadline for an exam. The students, supported by FESCI, argued that the registration instructions had been unclear and that excluding those who’d missed the deadline wouldn’t be fair.

Arnaud Vivien Grogba, FESCI’s deputy national secretary for academic affairs, organized the protest. He told me to be there at 7 a.m., saying he was expecting a high turnout. When I arrived at 8 a.m., though, no more than two dozen people had gathered, evenly split between would-be test-takers and FESCI members. Grogba explained that police had been deployed to the school’s entrance the previous day, scaring people into staying home.

It is tempting to conclude from FESCI’s diminished mobilization capacity that the group is becoming irrelevant. But many students say that, regardless of FESCI’s violent past, the group has a role to play on campus, and that there is a need for a strong union to represent them in disputes with university authorities and the government at large. One student, who gave her name only as Debora for fear of antagonizing officials, captured a common sentiment when she said, “Who can speak if not FESCI?”

The notion that students require a union to confront the state on their behalf underscores a longstanding divide between those in power and the country’s youth. As Mike McGovern writes in Making War in Côte d’Ivoire, campus violence during FESCI’s heyday “was turned against a government that had come to represent a calcified structure of illegitimate rent-seeking by elders who had mortgaged the younger generation’s future.” Though a 1987 World Bank study found that Côte d’Ivoire spent a higher percentage of its budget on education than any other country, a long, slow economic decline beginning in the 1980s meant that many students struggled to find jobs once they graduated. Ouattara has been rightly credited with turning the economy around since the war ended, but there is a general feeling that large infrastructure projects and foreign investment have yet to improve the lives of ordinary citizens. In this world of diminished opportunity, the promise of FESCI remains one of empowerment.

The trouble lies in the fact that empowerment as practiced by FESCI tends to come at the expense of non-members. This could be seen on the day of the Peace Fair, when the group turned on the very people — university students — it was supposed to be championing. FESCI’s leaders have defended their behavior that day, saying they decided to disrupt the fair because they had been denied space on campus for a ceremony marking their 25th anniversary. Assi, the current secretary-general, also said the altercation had been misreported, blaming the media for distorting facts to condemn FESCI for the violence. To the contrary, he said FESCI was merely responding to provocation from security forces. “No student would be violent against a fellow student,” he said.

But Assi’s version does not square with what witnesses remember. Arsène Tiénan Kouamé, a 31-year-old doctoral student, was donating blood at the fair when FESCI arrived and began turning over tables, forcing everyone to flee. Though he managed to get away, his laptop — which included months of data for a dissertation on conflict resolution — was lost in the melee and has not been found. Arsène had borrowed money from family and friends to pay for the computer, and he was not sure when he would be able to afford another one. The fact that FESCI had deprived him of a tool necessary to complete his work, he said, indicated that the group had yet to find its way. “The students need to be able to come together in a union. That’s normal,” he said. “It’s just FESCI’s manner of operating, of acting. That’s what can be a problem.”