BANGDONG, China — It’s widely known that China is a nation in flux. But it’s worth noting that the changes its people have seen in recent years are unlike anything experienced in any other country during any other time in history. Many cite Shanghai’s iconic Pudong district as a feat of modern development, transformed in just 30 years from poor empty farmland into a futuristic skyline with some of the world’s most expensive real estate. But to me, the transformation in rural China is even more remarkable.

Consider that most rural Chinese grew up in poverty with little or no education. Most people in their 60s endured unspeakable suffering during times of violent domestic chaos. Most in their 50s never got enough to eat and many are illiterate. Those in their 40s grew up without electricity, and most in their 30s remember their village getting its first television set—black and white—and completed only junior high school, if that. Now, not only do they all have more than enough to eat, but virtually everyone carries around a mini-computer in his or her pocket that provides access to information and opportunity no one could have previously dreamed possible. To live amid such drastic change requires uncommon mental and emotional capacities.

As I’ve gone about my daily life in Bangdong, a small village in rural Yunnan province, I’ve been privileged to encounter the people living through this transformation and marvel at their strength of spirit and ability to adapt. These are their stories.

Zhang Tianxue, the medicine hunter

Zhang Tianxue and I live in villages on opposite mountainsides. Our paths crossed, quite literally, on a walk through the connecting valley one Sunday morning. Zhang was hunting for medicinal plants and invited me to join, disappearing into the green foliage while I trudged up the water gully behind him. The air hung damp and musty from the decaying leaves underfoot. He plucked green plants—roots and all—from the mud, folding them into thirds and placing them into his feed sack-turned-satchel. He collects the plants for friends, and some even pay him. But Zhang doesn’t need the money. He makes about $20,000 a year now as a tea farmer—a staggering five times what he used to earn as a migrant laborer in big cities. “My son made me get a smartphone,” Zhang says. “The voice messaging is really useful because I can’t type and I can’t read without these,” he adds, adjusting his glasses on his nose. A sticker left on the prescription lens reads “+3.00.” “There are too many buttons on this thing,” he says sighing.

Yang Sanmudao, the moba

The Wa tribe is one of China’s 55 official ethnic minorities and boasts Wengding, “China’s last remaining primitive tribal village” deep in the mountains of southwest Yunnan province. Yang Sanmudao is a moba, what Wa call their spiritual leaders. He does not know the year he was born but he’s certain he’s past the 60-year-old minimum required to assume the title. Yang grew up in Wengding back when Nationalist armies would raid and loot their women and livestock. “We adore Chairman Mao for liberating us from Nationalist oppression,” he says. “And the biggest improvements to our lives have come from Deng Xiaoping Theory,” he adds, referring to the former Chinese leader’s economic reforms that began opening up the country to the world. We sit under a sprawling Chinese banyan decorated with a cow skull and a placard declaring the tree to be 500 years old. Yang boils tea in a kettle over an open flame and sings:

The Wa people sing a new song,

the Communist Party shines upon the frontiers.

The mountains smile, the waters smile,

and the people celebrate.

Wang Shuijing, the hairstylist

Wang Shuijing runs three different salons around the county, each open only one day a week when the rotating market passes through. She had to drop out of school in 6th grade to help in the fields and eventually followed a boy to a nearby city where she learned hairstyling. The boy didn’t pan out, but she has stuck with the craft. Shuijing now has a faithful customer base (myself included), is proud to be her own boss and dreams of having just one shop in the nearby city. “It’s hard work, but the money is my own,” she says.

Mr. Luo, the rice farmer

Mr. Luo is one of the few remaining rice famers in the region. Most locals have already converted their terraces to grow tea and sold off the water buffalo they once used to plow through knee-deep mud. Luo and his three water buffalo are finished plowing for the day. We chat on the terrace embankment while Luo, already shirtless, strips out of his muddy pants. I examine the clouds intently. “New tea trees take six years to produce a crop,” explains Luo, who turns 60 this year. “I can’t wait that long.” So he stays in the rice business, harvesting 3,300 pounds annually, of which 900 pounds feeds his family for the year. The rest he sells for about $2,000—roughly double the price of a new iPhone.

Yang Hao, the musician

Ninth place out of 1.4 billion isn’t bad. Last year Yang Hao sang his way to the top of “The Voice of China” and now manages competitions for the televised singing contest across Yunnan, organizing preliminaries in villages and towns of all sizes. Yang is Wa ethnicity, a group known for its music, although it wasn’t always encouraged in Yang’s family. His parents hoped he would focus on his high school studies to get into a good university. Competition for academic spots is fierce in China. Instead, Yang saved up his money, bought a guitar from a neighbor boy and practiced in secret. Yang’s father was furious when he found out and smashed the instrument to pieces. Yang recalls: “When I won the TV show, I was so happy because my dad saw that I’m actually really good at this.” Now he wonders what he can do for the Wa community. “Young people don’t care about our Wa language or songs,” he says. “They care about jobs and cell phones. Our culture is disappearing with the older generation.”

Zeng Yulan & Li Xiaoqing, the entrepreneurs

“We’re from Fulan province,” Zeng Yulan says. Her strong Hunan accent confuses “h” with “f”, and “n” with “l”, inventing the name of a new province and immediately giving herself away as an outsider. “We Fulan people like money so we’ll go anywhere,” she adds. Zeng’s daughter, Li Xiaoqing, admits that life in Bangdong is tough. “The conditions are bad, and business isn’t great,” she says, “but we can get by.” “And it’s easy to save money here because there’s nothing to spend it on,” Zeng adds. “No fun or good food—only mountains.”

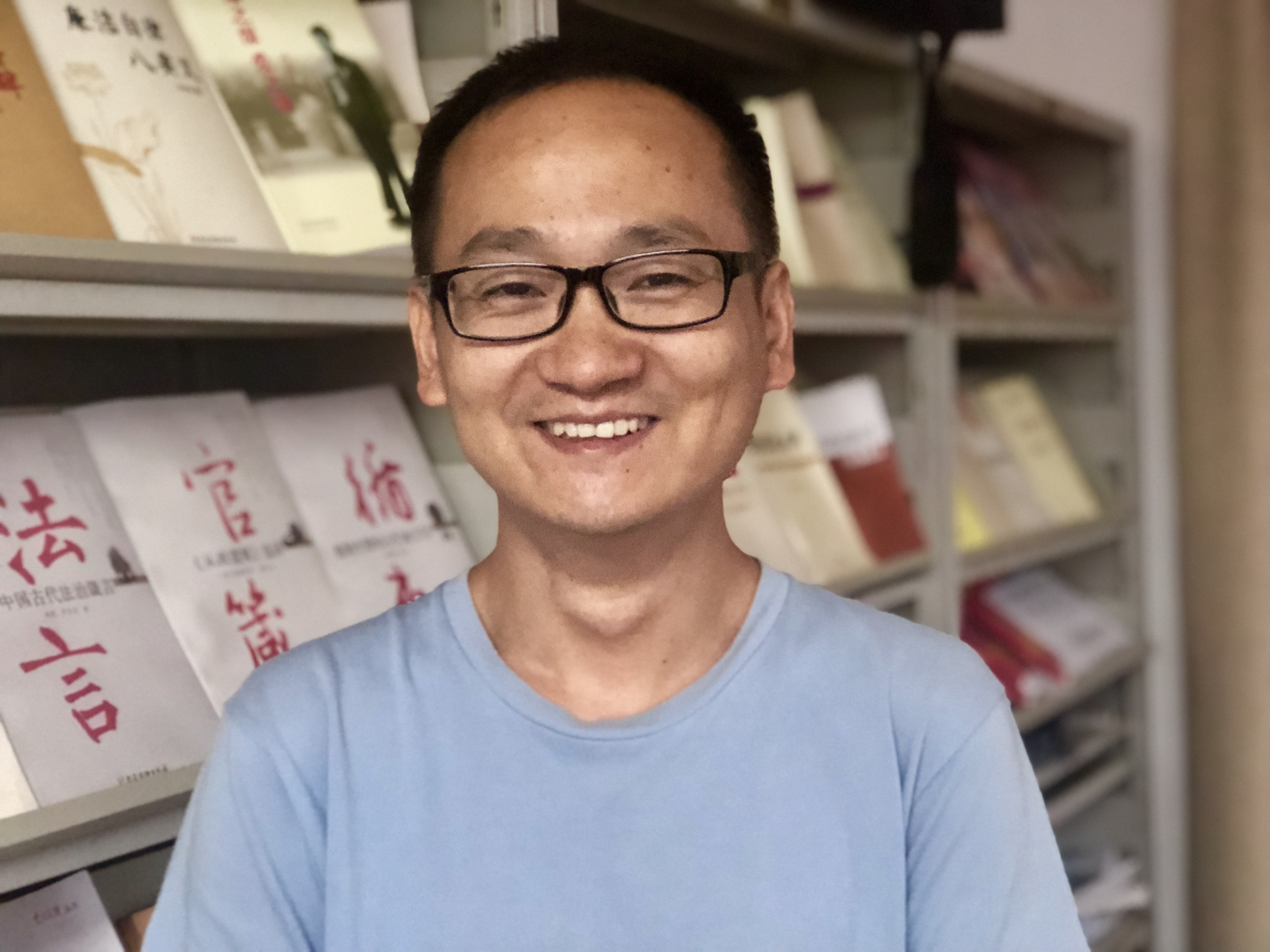

Xu Junsheng, the government official

After his cafe went bust a year out of university, Xu Junsheng tested for government service. “I needed stable work and wanted to give my parents face,” he says, admitting his intentions to have been self-serving at the time. Now, ten years later, he is deputy secretary of the Communist Party in Bangdong and finds the work meaningful. “We really do serve the people,” Xu says. “Providing good roads and housing, protecting our food and water, dealing with crises like landslides and flooding. Our work affects people’s lives at the most basic level.” When a mountain crevasse, gaping and growing, threatened to destroy local homes during last year’s rainy season, he helped relocate villagers and look after their daily needs. “Rural challenges mature you and hone your capabilities to address any type of problem,” Xu reflected.

Li Xueliang, the artist

Li Xueliang’s home is a mess of tarp and rope in the Five Old Mountain Nature Reserve, about 10 miles outside Bangdong. I peek in and discover one can fit a lot in nine square meters: a man-sized piece of plywood and a bedroll, a hotplate and water kettle, generator, stash of vegetables and a pile of paints. “Painting is a good gig,” Li says. The government has commissioned him to paint an introduction to Bangdong and a map of the region on a single wall that faces his temporary shelter. Li has been painting for two weeks and has little to show for it, just pencil outlines of characters and a blank white wall. “That’s where the map will go. I should be done by the weekend,” he says optimistically. I return a week later to two paragraphs of black characters separated by a map-less white expanse. “It’s going slowly,” Li says. “Maybe another week.” He is struggling with painter’s block. As a writer, I sympathize; but I can close my laptop, whereas Li’s blank screen, the size of a semi, looms outside his front door. The following week, I return again, this time to a penciled map and an upbeat Li. “I’ll make [$5,000] for this,” he offers, unsolicited. “That’s a bit more than a Party official makes, and a lot less risk. They can get in a lot of trouble these days,” he adds, referring to President Xi’s crackdown on corruption. On my next ride through Five Old Mountain Nature Reserve, a colorful map welcomes me to Bangdong. Li and his painter’s block are gone.

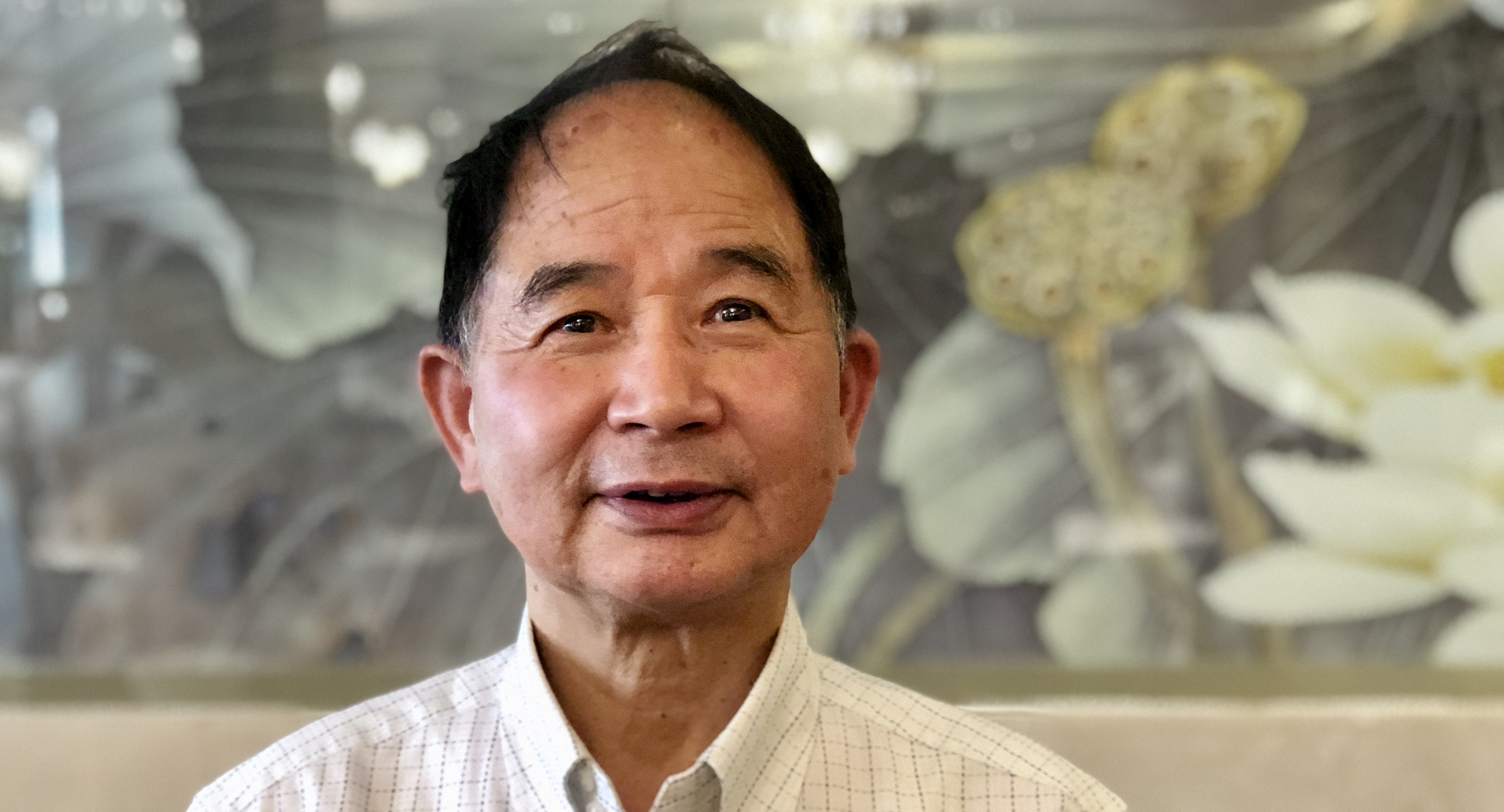

Lin Chaomin, the professor

Dr. Lin grew up in the countryside in western Yunnan not far from the Myanmar border. Today we meet in the provincial capital of Kunming, at The West Inn Hotel. (Not to be confused with The Westin Hotel… or is it?) Lin orders us two extra-large bowls of Cross-the-Bridge rice noodles, a Yunnan specialty. He is a Yunnan history scholar at Yunnan University and reminds me of the legend behind the name: a man studying for the imperial examination on a small island, a clever wife traveling a great distance to bring him food, and a rice noodle soup that was always cold and soggy by the time she crossed the bridge to deliver it. The waitress interrupts Dr. Lin’s story to deliver two steaming bowls of broth and side plates of rice noodles and uncooked chunks of chicken, bean curd, sprouts and chives. We dump everything into the oily broth and watch it cook as the professor concludes his lecture with a simple hand gesture toward the bowls. Between noodle slurps, he outlines the waves of immigration to Yunnan: a silver rush in the 15th and 16th centuries, the Ming dynasty fleeing the rising Qing in the mid-1600s, and the People’s Liberation Army fighting residual Nationalists and setting up outposts among minority groups after the Communist victory in 1949. He also describes his own journey: one of only four in his class to test into university; a degree disrupted by political campaigns; three years of re-education on a tea plantation in southern Yunnan; and six years getting Masters and Doctorate degrees once the university system was reinstated under Deng Xiaoping’s leadership in 1978. Dr. Lin has studied and taught at Yunnan University ever since. I jokingly ask if anyone made him Cross-the-Bridge rice noodles when he was studying for exams. “No,” he responds in earnest. “This meal was unimaginable. We had no food to eat then.”

‘Baby, the newborn’

I met Baby three weeks after she came home from the hospital. “We haven’t given her a name yet,” her father Cao Yong says. “We’re still getting to know her personality.” Cao Yong is from Chuxiong, a minority autonomous prefecture in central Yunnan, but they are staying with her parents in Bangdong for the month after the birth. “Sitting the month” (坐月子) is a traditional Chinese practice of diet and lifestyle restrictions to restore a mother’s health after giving birth. Practices range from common sense (rest and hydration) to the senseless (no brushing teeth or carrying the newborn), but for this young mother it means mostly staying in bed and not bathing or washing her hair. After “sitting the month,” they will go back to Chuxiong where Cao Yong’s parents are looking after their oldest child. “We probably won’t come back to Bangdong for three years,” he says. “I need to find a job in Chuxiong. Kids need their parents around for healthy development, so I guess we’ll be there for a while.”

Mao Wenshan & Li Changhong, the newlyweds

Their life-size photo greets me at the entrance. The courtyard features colorful streamers and a collection of knee-high tables and stools, ready to feed a village. The groom sits in the smoke-filled living room with his buddies, watching television and drinking beer. The bride sits in the corner by herself playing a Chinese version of Candy Crush on her phone. She is dressed head to toe in auspicious red and wore heavy make-up. “One hundred years of happiness!” I extend my best wishes to the young couple. We chat as peers until I ask their ages. The groom is about to turn 23. His bride is 15. Suddenly she appears like a child playing dress-up. “When family conditions aren’t good, people get married really young,” someone in the village tells me. “If you have money, you have options.”

A Hua, the truck driver

The ear-splitting roar of A Hua’s truck stops all conversation when he drives through Bangdong village. He bought his first Steed five years ago at the age of 19. For $5,000, he drove it fresh off the lot and soon had it decked out with rubber trim jagged like teeth and green shag carpet on the dash. Last week, A Hua traded in his old Steed and another $5,000 for a new truck, same make and model, same deafening engine, and same green shag carpet. “There’s work only two or three days per week,” he explains. “There’s just not that much to haul.” At $20 a day, A Hua will need about a year-and-a-half to pay off his truck. “He doesn’t have the brain to think about the future,” his father says. “[Twenty bucks] in his pocket is enough to get by today, so he doesn’t worry about it.” A Hua and his friends often sit shirtless in the courtyard drinking corn liquor and playing “Glory of Kings” on their cell phones. “I don’t know when he’ll get married,” his father continues, “or if he’ll be able to take care of his mother and me. He probably hasn’t thought about it.”

Ma Yanan & Yang Linqiao, the restaurant owners

There are three Muslim families in Bangdong. And there are three Muslim restaurants. Ma Yanan, Yang Linqiao and their four-year-old boy came from northern Yunnan six months ago after visiting a cousin in a nearby town. He owns a Muslim restaurant. “We made the right choice in coming here,” Ma says. “Because of tea, Bangdong’s economy is much better than in our hometown. And the people are really nice.” Ma is more optimistic than his wife. “Things are expensive here though,” Yang counters. “And business won’t be good when the highway opens up. People will go eat in the city rather than coming here.” Yang’s comment is the first I’ve heard suggesting the highway, which is scheduled to open in 2020, might bring challenges along with benefits. Ma looks at his wife reassuringly, “But we don’t worry about it. We can only take things as they come. For now, life is better.”

Grandma Li, the tea farmer

Grab-pinch-roll, grab-pinch-roll, grab-pinch-roll. Grandma Li’s hands waltz down the tea branches and fill up her satchel leaf by leaf. On a good day, she can pick upward of 30 pounds of tea and sell it for the equivalent of around $30. She and the rest of Bangdong’s women are the force behind the region’s tea economy. Women are better at picking tea than men, I’m told. Faster hands. Attention to detail. They pick from sunrise to sunset, pausing only to feed their families or when the summer rains make it impossible to dry their harvest. Now in her 60s, Grandma Li has seen dramatic change. “These fields used to all be rice and corn,” she says between branches. “We ate what we grew.” Now the surrounding hillsides are covered by tea terraces. She grew up in a small mud house with a grass roof and dirt floor. Now the entire third floor of their newly built home is blanketed by drying tea leaves. Grandma Li’s secret to success is a band-aid on her picking finger. “It prevents blisters so you can pick faster,” she confides. “And if you don’t get it wet, you can use a single band-aid for three or four days.”