TOKYO — Facing a row of handwritten drink orders, Akira the Hustler held his breath and glanced up with a gentle pout. “So busy today,” he said, exhaling, as he turned to grab two bottles of Japanese whiskey. At 9:30 p.m. on a Tuesday night, the bar’s single row of eight seats was fully occupied. A couple of patrons floated behind me, their elbows and highball glasses precariously perched atop a thin floating shelf. A soft peach glow bathed the narrow, second-floor hideaway—a warm oasis from the garish neon churn of the central Shinjuku district just outside.

That evening, Tac’s Knot felt less like a bar and more like an overeager host’s living room salon. Maybe it was the tidy chaos of books and magazines stacked beneath the stove hood in the corner, betraying the hand of a seasoned hoarder. Or the uncanny contrast of fine liquor bottles lined behind the bar, with the grandmotherly array of cups and saucers tucked just below.

Or perhaps it was simply Akira the Hustler himself—how naturally he wove between conversations as the evening’s sole bartender. At 56, his only signs of age were the wrinkles that deepened with each smile, each contemplative furrow, each raised-brow glimmer of curiosity. When he wasn’t mixing drinks, the broad-shouldered man bounded up and down the bar. He oscillated between Japanese and English, adjusting the volume of his voice to accommodate the different moods of each client. Behind his thick black frames, his gaze was always direct but gentle. Everyone felt like a regular because of the way Akira-san, as we addressed him, soothingly shape-shifted to our preferences.

Most customers were regulars, drawn not only to the bar but to Akira-san’s legacy. “If you care about queer Japanese art, you come find Akira-san,” one patron exclaimed. Akira the Hustler—a sculptural and visual artist by day with solo and group exhibitions across Asia—humbly bowed and proceeded to sign his companion’s copy of his memoir, A Whore Diary. First published in 2000, the same year as his debut solo show, the book catapulted Akira the Hustler from more niche corners of LGBTQ+ and HIV-related activism into Japan’s contemporary art scene.

A Whore Diary chronicled Akira-san’s experiences as a gay escort in 1990s Tokyo, transcending three layers of silence: sex, sexuality and sex work. In literature and in law, all three subjects were rarely discussed, relegating a life like Akira-san’s to invisibility.

For example, Japanese laws on sex work, then as now, focused on female sex workers who catered to men, leaving male escorts like Akira-san in a legal gray zone: unregulated and unsupported. This vacuum continues to leave them particularly vulnerable to HIV/AIDS, sexual assault and other forms of workplace abuse, with little protection or public sympathy. Moreover, although the HIV/AIDS crisis had abated by the time A Whore Diary was released, its stigma still clung to gay male bodies.

“If I gather the strength to look back to when the first edition came out, it was as though the specter of queer death floating around us was equivalent to the number of us alive,” Akira-san wrote of the crisis in the preface of the book’s third edition, published in 2024. Akira-san himself turned toward art when a close friend and fellow artist died of AIDS in the mid-1990s.

But in defiance of the death-laden narratives that dominated LGBTQ+ media coverage, A Whore Diary celebrates lovers, friends and clients who not only survived the height of the epidemic but found healing through sex and intimacy. Formatted as zuihitsu—a pre-modern Japanese genre that mingles prose and poetry into a bricolage of fragmented thoughts—the book is impressionist in the way it unfurls, each passage revealing how much color exists beyond the epidemic and its scars.

In one vignette, a 70-year-old client asks Akira to recreate a physical memory from his time in the military barracks during the Pacific War—just a caress at the nape of his neck. In another, a 23-year-old HIV-positive client, terrified of his diagnosis, seeks Akira as his sole source of emotional solace. “I realized that if I let him go home without regaining his confidence, then he might never have sex again,” Akira writes. “I instinctively pushed him onto the bed and we passionately made love.” The client returned again and again until three months later, the client shared that he had finally come out to others and even fallen in love.

Still, in the spaces between his laughter, something somber surfaced. Barely looking up as he continued stirring a drink, he murmured, “It was, is, lonely being a queer visual artist in Japan.” This, too, he said matter-of-factly. It is a fact that many of his peers were lost to the pressures of being queer in Japan, be it the HIV/AIDS crisis or the difficulty of coming out. It is a fact that few openly queer artists from his generation remain alive, let alone in the public eye, today.

Although multiple surveys confirm that close to 70 percent of Japanese people are in favor of marriage equality—not yet legalized in the country—queerness remains laden with stigma. In Japan, the absence of comprehensive anti-discrimination laws inclusive of sexual orientation and gender identity leaves LGBTQ+ individuals vulnerable to discrimination. While the Act on the Promotion of Citizens’ Understanding of Diversity of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity, enacted by Japan’s national legislature in June 2023, represents a step toward awareness, it lacks enforceable measures to prohibit discrimination or penalize violations.

Researcher Masami Tamagawa describes the result as a quiet (otonashii) homophobia that pervades workplaces and broader society. On the other hand, familial (uchi) homophobia privileges the heteronormative trinity of father-mother-child, making it difficult for LGBTQ+ people to come out at home. A 2025 survey by ReBit, a Japanese organization focused on queer youth, found that over 40 percent of LGBTQ+ teens had no one to confide in safely, leaving many to navigate their sexuality in isolation and often triggering depression or suicidal ideation.

For Akira-san’s generation, these familiar contours of queer loneliness are painted with scars from the HIV/AIDS epidemic, when safe public spaces and queer visibility were even scarcer. “Our days are demarcated by the repetition of little goodbyes,” Akira-san wrote as a stand-alone Diary entry. Different goodbyes, of course, carried different weights. Of a friend who passed away from AIDS, he wrote, “We spent the night before his burial together. I kissed him, and indeed, his lips were cold.”

Other Diary fragments recount the alienation of sex work—the ache of always giving but rarely receiving. “Someday I myself want to be able to use those words,” he wrote, referring to I love you. Another entry catalogued gifts from clients—a glittering archive of the givers’ absences.

In the 2024 preface to A Whore Diary, Akira-san revealed that he had hit rock bottom in 2016: homeless, drifting between gay saunas, contending with HIV. It seemed as though waves of grief slammed against him with more and more force. But each time, he outlined the bruises left behind—his lover’s scars, a door softly closing behind another client, a dead friend’s lips—learning what grief looks like and, by extension, learning how to face it.

In a culture that so often neglects queer lives, Akira’s stream-of-consciousness becomes a counter-archive—not just of sex work and its contradictions, but of the care, survival and goodbyes inherent to the Japanese gay/queer experience in the 1990s. He does not purport to have transcended the trauma of the AIDS crisis or found a formula for counselling young gay men through their self-loathing. All of this is just another part of life’s constant going—but that journey of becoming need not be as lonely as it was two decades ago.

As he wrote in the 2024 preface, “We are misguided to associate life with light and death with darkness. If so, why do dying stars shine the brightest? If so, how would their lights continue to guide those of us who continue to sojourn, toil away in our boats of life?”

Seeing him in person at Tac’s Knot—where he has bartended every Tuesday for many years, a captain among friends and patrons—was the greatest affirmation that it’s possible to endure the grief, the loneliness, the painful and darker moments of being queer. And still glow.

This is a story about artists reformulating how queer bodies are seen in Japan—pressing against conformity and broadening the conventional terms of beauty.

* * *

In “Individualists,” a 2021 installation by Akira the Hustler at Tokyo’s Ota Fine Arts gallery, a flotilla of clay figurines drifts mid-air, each one perched in a tiny raft suspended by string from the ceiling. No two are alike. Some are standing, others are toppled over as if just rocked by a wave. Each figure’s clothes broadcast a different political message: “Nuke is over. Black, queer, dope. 99°C,” referencing a South Korean manga about the country’s 1980s democracy protests. “If the temperature rises by one degree, we might reach the boiling point,” a character mutters in the manga, foreshadowing the potential for revolution. While the title “Individualists” gestures to the singularity of each figurine, they all grip wooden paddles, united in their quiet pursuit of an elsewhere, a future just beyond the present.

To me, Individualists calls to mind the social theorist Sara Ahmed’s notion of an “affinity of hammers.” Writing in 2016, the feminist scholar described how being hammered by gender norms and heteronormativity can teach one to pick up the hammer in return and chip away at those very systems. In doing so, we’re drawn to others who also resist, hammers in hand, dismantling the worlds that seek to confine our bodies. But in Akira-san’s hands, the hammer is reimagined. His figurines trade ferocity for something softer, more speculative: a paddle, not a weapon, suggesting not destruction but direction. As different movements and identities encounter each other in this suspended moment, a shared current of solidarity begins to emerge.

Individualists also feels like an apt metaphor for queer Japanese art, which pulsed quietly but powerfully through several museum and gallery exhibitions in the lead-up to this year’s Tokyo Pride—one of the largest Pride events in Asia, with more than 250,000 annual visitors. In those shows, I encountered a constellation of artists who, like Akira the Hustler, have memorialized life on Japan’s social margins, while also building alternate universes, effigies and portals that hold a mirror to gender and other social norms we’ve been taught not to question.

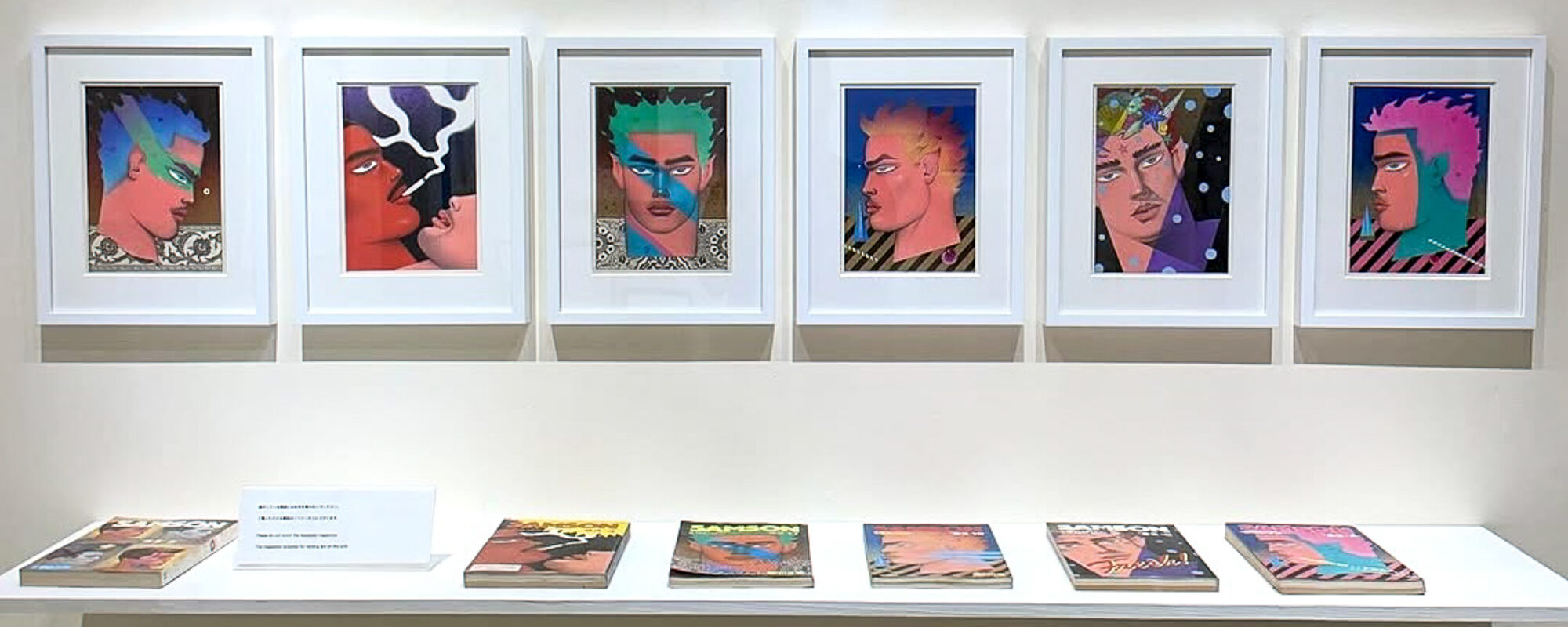

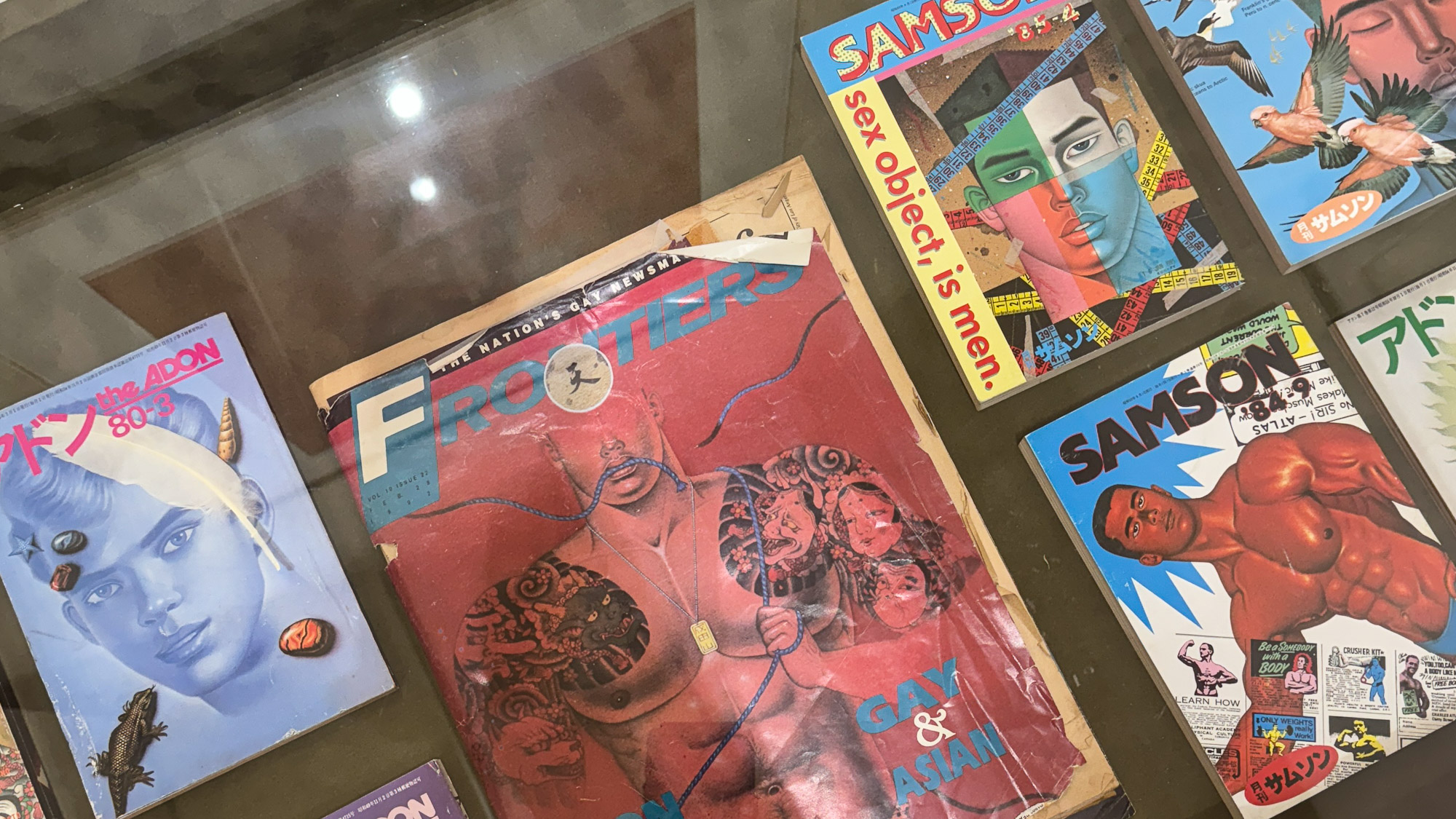

Among them, few artists rival the visionary world-building of the late Sadao Hasegawa, long considered one of postwar Japan’s most important creators of gay erotica. In vibrantly colored works painted with lush, fluorescent acrylic and laced with glitter and gold, Hasegawa envisioned a queer universe populated by chiseled, well-endowed Asian men exploring their sexuality without societal or even planetary constraints. Many of his figures are suspended mid-penetration; others are bound in shibari, muscles swelling against intricate lattices of rope. Some float freely, pulsing with orgiastic energy in a boundless cosmos where—in an ecstatic fusion of Japanese, Indonesian, Thai, Indian, Buddhist, and psychedelic motifs—nothing is unnatural. For example, in “That Floating Feeling,” commissioned for the cover of the pioneering gay magazine Barazoku in 1990, a flaming spirit reminiscent of the Hindu god Agni rockets through space, exhaling a starry nebula from parted lips.

Hasegawa is often dubbed the “Japanese Tom of Finland,” a nod to the Finnish artist whose iconic portrayals of gay fetish, as the art critic Kate Wolf wrote, “paved the way for gay liberation.” Both artists unapologetically foregrounded hypermasculine desire and fantasy at a time when gay male bodies—and in Hasegawa’s case, the racialized Asian gay man—were widely dismissed as effeminate.

At Gallery Naruyama, which manages Hasegawa’s estate, a spring show of the artist’s 1980s magazine illustrations surrounded me with razor-sharp jawlines and stoic stares. At first, their machismo felt forbidding. I struggled to make sense of these bodies—their ideal of masculine detachment, their rigid standards of beauty.

But the deeper I went into the archive, the more their differences from Tom of Finland’s leather-strapped bikers came into focus. Hasegawa’s figures are less brash, more interior. Their energies don’t confront; they radiate gently, absorbed in their own or a sexual partner’s spiritual rapture.

Perhaps it’s the way fluorescence fades into pastel shadow, softening each muscle with a dreamlike haze. On one wall hung a series of sketched faces: eyes closed, lips slightly parted, as if asleep or in meditation. Elfen ears curled skyward, dissolving into ember-like halos of hair. Each bore a unique color of blush across the cheeks and a different emblem between the brows—a star, the Chinese character for “moon”—marking them as deities in his cosmology.

When I later learned that Hasegawa died by suicide in 1999 for reasons that remain unknown, I began to see his figures differently: not only as erotic archetypes but as armor. Very little is known of Hasegawa’s life; even gallery owner Akimitsu Naruyama was surprised to inherit the artist’s entire estate, a decade after meeting Hasegawa only twice. I wondered if Hasegawa’s interest in Asian spirituality stemmed from a search for new models of strength, disillusioned with the world’s binary insistence of masculinity and femininity. Or, in taking his own life, I wondered if he was simply escaping into an entirely different dimension, where queer Asian male beauty could be worshipped, where queer sex and sexuality were so abundant that the boundaries of fantasy are pushed into the unknown.

Hasegawa’s visions reached thousands on the covers of gay magazines like Samson and Barazoku—lifelines for Japan’s discreet queer community throughout the last quarter of the 20th century. Barazoku, launched in 1971, produced 400 issues over three decades and pioneered the concept of a glossy, nationally distributed gay periodical that could be found even in mainstream bookstores. Ads for bars, bathhouses and escorts mingled with comics, confessions and painstaking how-to guides. One Samson I leafed through from 1983 offered step-by-step tutorials on shibari knots, followed by elaborate descriptions of bondage trysts. While Hasegawa’s covers invited readers in, these magazines’ back pages were proto-dating apps: one-paragraph personals of men looking for sex, love and manifestations of Hasegawa’s visions.

These gay magazines laid the foundation for a shared consciousness among gay men in Japan. But that consciousness encompassed the legal limits of their sexual expression. To avoid encounters with the state’s moral police, pixelation blurred explicit photography and ink blots masked genitals—constant reminders that the country preferred its queer citizens unseen. In photographs, eyes hid behind black bars; they, too, did not want to be recognized. (It wasn’t until the mid-1990s, with gay magazines like Badi and G-Men, that the faces of everyday gay men were printed openly.) Hasegawa even avoided overseas exhibitions for fear that Japanese customs might seize his canvases under obscenity laws.

To paint his flaming deities and rope-bound acrobats under these conditions, then, is even more exceptional. He gave a visionary visual language to the fantasies and brief orgiastic encounters described in these pages: See yourselves in us. Guard your radiance; honor your desire.

I can’t help but interpret those figures as self-portraits—Hasegawa immortalized in celestial form, looking down on us, urging us to keep building a world where all our queer Asian bodies are loved.

* * *

If Hasegawa invited us into a cosmos where queer Asian male beauty is exalted, his successors are challenging the societal and legal codes that continue to hem in that vision of identity and beauty today. In a culture wary of flux, where the state-sanctioned view of “Japanese-ness” promises homogeneity and sexual morality, contemporary queer artists are keen to expose those scripts, until stereotypes of queer people split at the seams.

No one has made that case more quietly, yet more unequivocally, than Ryudai Takano. He’s often filed away as a “gay photographer,” a shorthand drawn from his nude studies, snapshots of male intimacy and gender-fluid self-portraits. Works like “Reclining Woo-Man” (1999) and “How to contact a man” (2009) show naked men sprawled on white sheets, rendered in unguarded close-ups. These are neither Hasegawa’s mythic beefcakes nor conventionally idealized bodies. As the curator Kuraishi Shino notes, Takano is less interested in nudity or erotica than in society’s gaze: the desires and assumptions that shape how we look at nakedness in the first place.

That interest is explicit in Takano’s award-winning photo book IN MY ROOM (2005), where he splices the upper and lower bodies of different models—lovers, friends, family—while concealing their genitals and other private parts. Clothing or makeup may hint at gender, but the series ultimately withholds certainty, laying bare (as the scholar Takashima Megumu writes) “the gaze that reduces the criteria for determining sex to body parts like breasts and genitals,” and exposing the illusion that nudity guarantees knowledge.

At the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum earlier this spring, Takano’s career-length retrospective, “kasubaba: Living through the ordinary,” folded his studies of gender and sexuality into a larger project: prying open how we see the world. His long-running “Daily Photographs”—for which Takano took at least one photograph a day since 1998, of street corners, half-eaten meals, the slow drift of shadow across concrete—treat the camera as a device for testing vision’s habits and limits. Like Takano’s nude studies, these pictures ask not only what deserves attention or recognition as beauty but how a change in vantage reshapes what we think has value.

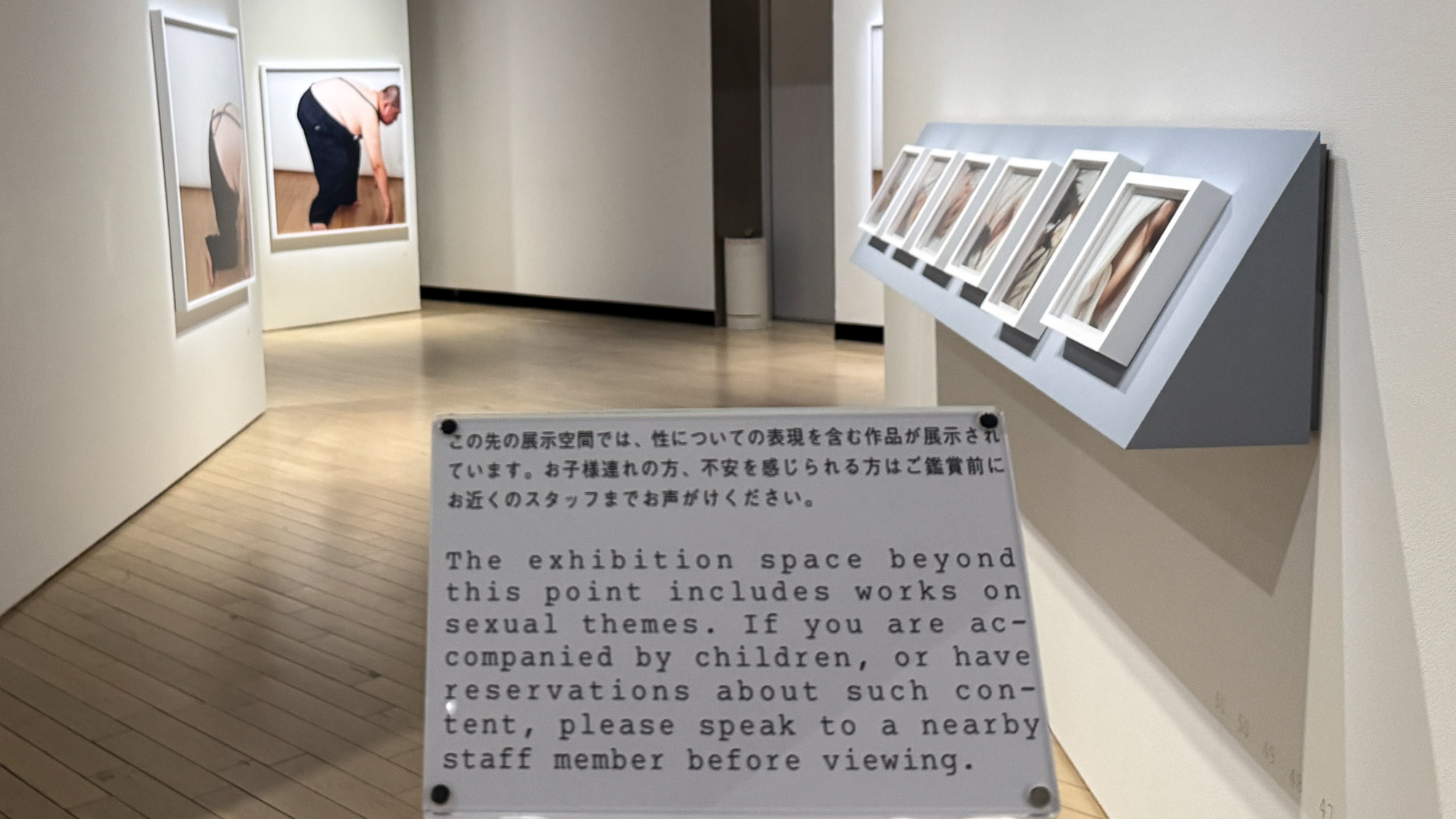

For Takano, these are not merely aesthetic questions. In the exhibition’s centerpiece, titled “2017.06.12.L.bw.#07,” Takano builds upon a moment when his work butts heads with the Japanese state’s surveillance and censorship regime. In 2014, Takano exhibited photographs from his series “with me” as part of a group photography exhibition at the Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art, located in Nagoya. Although the series began as a study of skin tone and light—Takano standing nude beside his models (mostly men), arms draped over shoulders to calibrate color—it evolved into a matter-of-fact study of male intimacy.

After the opening week, the police demanded the museum remove the works, arguing that visible penises made the images chargeable as the “distribution of obscene objects.” There is no clear statutory definition of “obscene” in Japan, yet authorities have long treated explicit genital display as such. “I suspect the officer’s insistence had less to do with penises,” Takano later said, “than with his distaste for two naked men happily standing together with their arms around each other.”

Takano answered by veiling the images himself—wrapping the figures in a near-translucent white cloth like bedsheets. Compliance became critique: Viewers could watch the state’s script being written onto the body in real time. For many, the intervention made the absurdity of Japan’s obscenity regime plain, and, as the curator Nakamura Fumiko observed, the cloth “reinforced the homosexual aspect of two men in bed and transformed it into a message of political resistance.”

In the current retrospective, “2017.06.12.L.bw.#07” was hung in a walled-off alcove, with a staff member and a notice about nudity. In the photograph, Takano and a nude model stand with their bodies turned to one another, faces staring directly at the camera, each grasping the other’s penis. Here, the genitals are covered—in this sense, “less obscene” than the 2014 prints—yet the shared touch is erotically suggestive of foreplay. The model holds the cable release used to trip the shutter, a small theater of control that’s already been decided: the image exists, and we are its witnesses.

Takano himself wrote of the photo: “It contains no special message. There are no attractive, buff physiques on display. Just two people with unreliable bodies, unguardedly exposing their nakedness.” Set against the airbrushed ideals of gay porn, the censored faces in old magazines and the armored perfection of Hasegawa’s gods, Takano hammers away at both the authorities and our community’s own internalized perfectionism with something more fragile and therefore more radical: soft, silly, naked men—simply human.

That insistence on ordinary, fallible bodies was also foregrounded in another exhibition. At the Shinjuku Ophthalmologist Gallery, the “Queer Art Group Exhibition”—self-organized for the third time by the artists Yudai Takeuchi, Tatsuru Hatayama, Kazutaka Nagashima and HEY2—picked up Takano’s thread from the side of memory and care. Four men from their 20s to their 40s turned the white cube into a one-room shrine: oil paint, video, woodblock and small sculptures attending to the soft, unguarded moments that men in Japan are rarely permitted to show.

Nagashima’s woodblock prints (mokuhanga), hung above a bed of dried rose petals, were the first to catch my eye. On a trip to Taiwan, the artist had heard pop diva Jolin Tsai’s 2018 electronic dance track “Womxnly” (玫瑰少年) and learned that it honors Yeh Yung-chih, a 15-year-old boy bullied to death for his gender non-conforming behavior. Yeh’s case catalyzed the passage of Taiwan’s Gender Equity Education Act four years later in 2004—a rare instance of grief bending law toward protection.

In his artist statement, Nagashima recalled how in 2015, a student at Tokyo’s Hitotsubashi University committed suicide after being forcibly outed. As a Human Rights Watch report from 2016 noted, “Hateful anti-LGBT rhetoric is nearly ubiquitous in Japanese schools, driving LGBT students into silence, self-loathing, and in some cases, self-harm.”

“Their lives were quietly buried under society’s indifference, eventually fading from collective memory, like myths or fairy tales,” Nagashima wrote. “I wish to transform them into roses—to etch into the world the fact that their beauty and suffering truly existed.”

In Nagashima’s “Rose Boy”—also the direct translation of Tsai’s music track—two figures curl into fetal poses atop overlapping beds of roses. Leaf clusters veil their faces; their limbs dissolve into the patchwork of petals and thorns. Tsai sings, “Which rose doesn’t have thorns? / Let your beauty be the best revenge / Strike back with your blossoms.” Nagashima’s boys seem to be resting, gathering themselves to bloom, mustering the confidence to stand out and reveal their beauty. Where traditional Japanese woodblock prints often linger on the fleeting grace of landscape, Nagashima turns the genre toward endurance, fixing these rose boys not only as natural, but as needing time to bloom into themselves.

If Nagashima tends grief into bloom, Yudai Takeuchi turns masculinity into maintenance, critiquing how Japan’s patriarchal foundation leads men to neglect self-care. In the watercolor painting “Cure,” a man stands in the corner of his bedroom and pensively looks down at an iridescent light cupped in his hands. Attention is first aid in a greyscale world devoid of emotional range and care. “I have seen people close to me suffering self-sacrificially from masculinity,” Takeuchi noted.

Across the room, in his work “The Blue House,” HEY2 pays tribute to a childhood ravaged by the gender binary. A series of dollhouse facades stretched across the wall; their exteriors are all baby blue, but their bright-pink interiors are full of sculptural and collaged chaos. Barbie dolls appear with vaginas for faces, an ongoing series that explicitly calls out the objectification of women. Trapped in blue houses, HEY2 provokes men to consider how female objectification enhances the confinement of their masculinity. In one house, the words “Prison Power”are written above and below the house’s singular window; behind it, the curvature of a female body is tightly padlocked within. “This is the house reflecting how I felt when I couldn’t dress up as Sailor Moon, and instead had to play Tuxedo Mask,” he wrote, the latter referencing the male protagonist of the beloved Japanese anime “Sailor Moon.”

Finally, in his video installation “Life is bitter,” Tatsuya Hatayama travels from Yokohama to Fukuoka—a distance of 1,000 kilometers—to meet an online friend. The two men stayed together for four days, and the video follows their relationship as awkward small talk unfurled into intimate exchanges. At one point, the two men bake a birthday cake and ice the video’s title across the top. In an attention economy pegged to social media clicks and comments, Hatayama’s video evaluates the strange but loving contours of our loneliness and longing.

Across the entire show, the artists’ queer identities are present but not necessarily the core of their work. I think of Takano’s shrug when asked in an interview about the models who appear in the “with me” series: “You can probably guess… I don’t think it’s important.” Takano and these four younger queer artists each push back against a society that over-prescribes who men are allowed to be and how they may relate to one another. As Jonathan D. Katz argues in About Face: Stonewall, Revolt, and New Queer Art, queerness is less a fixed identity than “the abandonment of who you are taken to be.” In the context of these works, queerness is less an essence than a passage: the ongoing work of slipping past tidy, state-sanctioned definitions of self and reclaiming the terms of who we are.

* * *

From Hasegawa’s first magazine covers to the new artwork featured in “Queer art Group Exhibition,” Japanese society has changed quite significantly. The shared consciousness sparked by the gay magazines of the 1980s has continued to blossom, and a concurrent rise in gay businesses, LGBTQ+ NGOs and internet culture has expanded opportunities for Japan’s LGBTQ+ population to meet, organize and imagine community. Every queer space I visited in Tokyo left me impressed, from the warmth at Pride House Tokyo (a community center and café established in 2020 on the outskirts of Tokyo’s gay mecca in Shinjuku Ni-chome) to the breadth of programming at KOSS SaferSpace on University of Tokyo’s Komaba campus, which provides an intellectual and social home for queer students and faculty. Moreover, a civil partnership system now exists in at least one municipality in each of Japan’s 47 prefectures, extending some rights to same-sex couples that straight couples have long taken for granted.

Still, Japan remains largely homogeneous and conservative. The issues queer artists tackle in their work—and by extension, the stigma, discrimination and limits of imagination that Japan’s LGBTQ+ people still face—do not seem to have changed as much as one might hope, even if their approaches have evolved from the more fantastical imaginings of Hasegawa to the social critique in Takano’s photographs. Even as public support for same-sex marriage has climbed to over 70 percent, traditional values persist, particularly within political and institutional power.

For the bookseller and graphic designer Yo Katami, this contradiction energizes his project loneliness books, his independent publishing press and bookshop. What started as a stall at Tokyo Rainbow Pride 2019 distributing queer Asian zines became an appointment-only store within his apartment during the pandemic, and eventually Platform3, a brick and mortar bookstore in Tokyo’s Higashi-Nakano launched with fellow indie booksellers TT Press.

On the fourth floor of a nondescript white building, a bold red door marks Platform3’s entrance; the adjacent wall is plastered with movie and manga posters. Inside, books, magazines, zines, comics and photo tomes are stacked in generous, teetering abundance. While Katami focuses on gender and sexuality in Asia, he and his co-operators’ interests are ever-expanding. In one corner, zines and nonfiction books on Hong Kong’s social movements sit beside dissident comics from China. Turn around, crouch down and there’s a run of books on Thai food. Next to a sign that reads, “Welcome to the dark queer side,” with “queer” in rainbow font, I found works of Li Kotomi, an award-winning trans Taiwanese author and translator who publishes primarily in Japanese. There is also a collection of books published from the United States and Europe, including a copy of The Queer Arab Glossary by the valiant London-based Lebanese graphic designer Marwan Kaabour.

Except for a large window that looks out onto the subway platform, every wall is shelved and stacked, even half-obscuring another set of window shades. In the company of Katami and Yu-hsiang—the Taiwan-born, Tokyo-based traditional Chinese translator of A Whore Diary—I spent three hours combing through this cozy universe, which also features a small seating area and space for rotating art exhibitions. Yu-hsiang told me Platform3 frequently hosts intimate gatherings, book launches and Pride Month events that give Tokyo’s queer community a place to land.

“Every opportunity to meet a book may also bring a little hope,” Katami said in a previous interview. “But when those who want to change society are powerless and tired, a space or publication like ours may become the place where they can replenish their energy. I think such places will become more needed.”

A zine-maker himself, Katami amassed his collection through travels around Asia, exchanging works and ideas with other artists during Pride markets and art-book fairs. “I want Japanese people to know that society doesn’t need to stay the same or have to change so slowly,” he told me.

Republishing A Whore Diary with a new Chinese translation in 2024 was also part of this mission. The book had long been out of print. A Korean-Japanese edition appeared in 2018 via a small Korean press, and its initial English-Japanese edition was first published by a Japanese art gallerist in 2000. In the 24 years between the book’s first and third editions, very few books in Asia have shared stories of gay sex work in as candid and dignified manner as Akira-san’s memoir. (Midnight Blue, published by the Hong Kong-based NGO of the same name, is the only other example that comes to mind.)

Katami hoped that the memoir’s “deep sense of love and emotion” could become a companion for even more queer readers and open the channel for cross-cultural dialogue. If I am any indicator, it’s working. A Whore Diary was the starting point for this article; Yu-hsiang brought me to Tac’s Knot that evening, where I met Akira-san and learned about the other exhibitions. From them, I’ve gathered a quiet determination to rewrite how Japanese society—and the world—sees its LGBTQ+ people.

In the newest edition, tucked between the foreword and the text, is a sequence of blurry film photographs taken by Akira during the period the book covers—images cropped intimately or softened like dawn’s first light. Even in the photos of Akira or his ex-partner asleep, there’s motion: roses rustling in the wind on the previous page; the crisp crinkle of white sheets. Before a single word, readers are ushered into Akira the Hustler’s sensual universe, invited to finish the hazy details with our own sense of love and sexuality.

The penultimate image shows Akira in a green bomber jacket at night, right arm hooked around a telephone pole. He smirks at the camera—mischievous, suggestive—daring the photographer to come closer. Turn the page, take the dare: a single white arrow on a grainy black field.

“I think that art, in a narrow sense, is the ‘slowest tool’ for having an impact on society and solving social problems,” Akira told the Ota Fine Arts gallery. “But this slowness is interesting.” No matter how slow, no matter how hazy, these artists press onward and upward.

Top photo: Illustrations by the late artist Sadao Hasegawa at Gallery Naruyama in 2025