The following is an adaptation of remarks I delivered at ICWA’s semi-annual gala on June 2 at the Cosmos Club, Washington, DC.

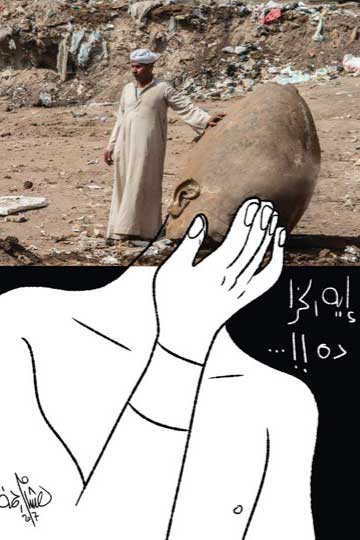

On March 6, a colossal head of an ancient pharaoh was uncovered in a 10-meter deep pit in the city of Matariya, an hour north of Cairo. The excavators wrapped it for protection overnight in a Spiderman blanket, probably the first thing they saw lying around. It was a gift to Egyptian jokers and meme-makers on social media. Such is Egypt in 2017, where the ancient and modern collide on a daily basis. The pharaonic past is inescapable, unearthed in this instance as civil engineers were plotting a new shopping arcade.

A week later, I took my little cousin to the Grand Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square. After spending hours touring the museum, lo and behold, we saw the colossal head sitting in a busy courtyard amid dozens of other massive statues. There was no room in the museum itself for this latest gargantuan find!

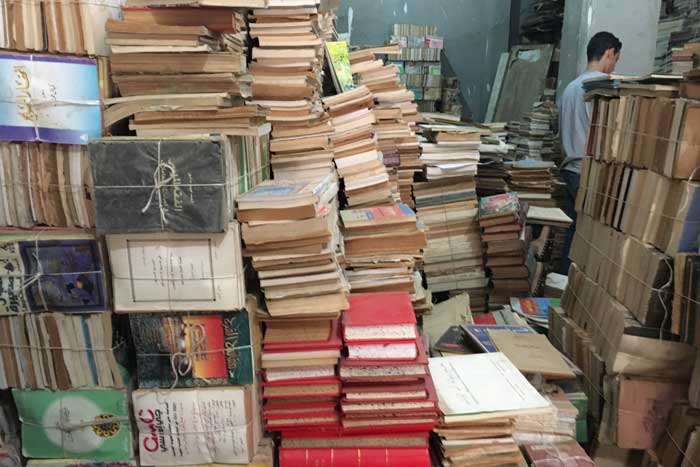

My fellowship has been focused on the present, recent past and future of Egypt. Yet even as I was examining the 21st century, hints of the past always popped up. Like the afternoon I discovered a black market for antiquities near the Friday market, a sprawling flea market where—if you know where to go—sellers hawk little ancient artifacts alongside the wares of T-shirt salesmen. Ancient motifs are also regular fixtures in the iconography of art and cartoons and comics, where jokes about the Matariya excavation were outrageous.

Naturally, when most people think about Egyptian art, they picture the ancient—Tut and Nefertiti and so on. But since the early 20th century, Egypt has developed a vibrant culture of fine art, an elaborate literary fabric, and of course a rich tapestry of cartoons and comics.

Exploring those passageways has been the goal of my two-year fellowship. I have focused on new stories of artists, cartoonists, novelists, journalists and other agitators who offer novel ways of thinking about a region that is too often reduced to terror and conflict. Indeed, the Western media has offered a monochromic view of the Middle East, sensationalizing terrorism and conflict while overlooking more complex narratives. Whether reporting on the Muslim Brotherhood or the Islamic State, news outlets latch onto strife, projecting the region’s fault lines with little context. The Middle East’s significant cultural and social currents are scarcely discussed. The American public rarely hears about new books, films or music from Cairo even though the city could be called both the Hollywood and New York of the Arab world.

Discussing the region’s cultural trends regularly in print and on TV and radio, I have begun to change the equation. My goal as a fellow over those two years has been to offer a new lens into Egypt—one that is absent from the headlines. I began searching for stories in cartoonists’ offices and migrated into artist’s studios, literary salons, editorial meetings, museums, libraries, lecture halls and comic cons, as well as openings and, invariably, closings.

I started by buying every newspaper every day and clipping the cartoons. I soon discovered that it was impossible to think about comics without also meeting artists and novelists and diving much deeper into society. And I have expanded my research from cartoons to a range of other creative productions over the past two years, learning about art, media and literature in addition to satire in the process.

“They paved Tahrir and put up a parking garage,” my first newsletter, from May 2015, began. I argued that in the absence of politics—that is, amid political repression and autocracy—art has become the public square. That led me to an open-ended question I have gone on to ask just about everyone I have met: What is the role of the artist today?

Along the way, I quickly realized that art is not just a “soft” topic. Indeed, it gets to the heart of politics and society, often in a more compelling way than “straight news.” In a country where scores of regulations limit free speech and expression, the burden on art and creativity are much higher. At the same time, a Soviet-style state such as Egypt depends on artists and intellectuals to support the government; at various points throughout the past four years, Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi has held meetings with “intellectuals”—that is, state-approved intellectuals—to seek out their counsel and bathe in their legitimacy. Usually they are just meant as photo ops.

When Sisi was running for high office in May 2014, his official account tweeted that artists are “the heart and soul of the nation.” Writing about that at the time, I mused that a nation of some 90 million has many consciences and no shortage of dissenting creators.1 They are the voices that I have attempted to amplify and share.

Egypt today

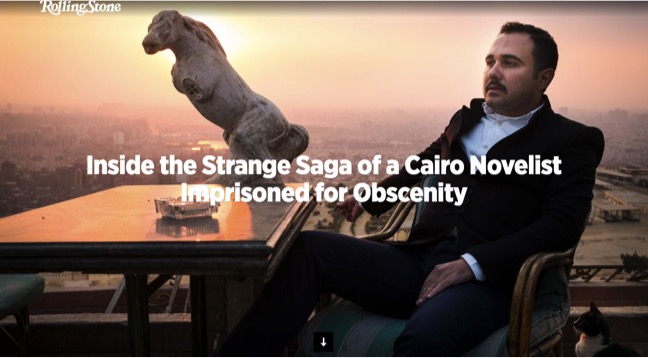

I was able to devote a year-and-a-half to investigating the strange saga of the Egyptian novelist Ahmed Naji, whose offending prose landed him in prison for much of 2016. Over that period, I attended numerous court hearings, conducted dozens of interviews and wrote three newsletters on Naji’s plight, which came together as a feature for Rolling Stone in February 2017.2 ICWA’s support meant I was able to closely track Naji’s story, while many busy journalists working for daily newspapers didn’t have the time or bandwidth to pursue the story over the long term.

I first met Naji in the fall of 2015, when we were speaking together on a panel about Arab comics at Townhouse Gallery, a Cairo art institution that the local authorities raided in January 2016 and was subsequently shuttered for much of the year.

I chose to pursue the story because of a moral obligation, a realization that hit me when I was attending an appeal hearing for Naji in July 2016. The image of a man I knew standing in a cage in a smoky, foul Cairo courtroom motivated me to ensure his story had a wide audience. His conditions were inhumane and emblematic of a generation being squeezed by a corrupt system. It took 18 months of work to get to the bottom of the story with as many twists and turns as a novel that Naji might have written.

We celebrated in May, when Egypt’s highest appellate court threw out the verdict and called for a retrial on the absurd charge of “disturbing public decency.” But Naji still can’t leave the country, and his case remains unresolved.3 He remains in limbo.

Egypt yesterday

Many reporters parachuted in to cover Egypt’s revolution, but I have discovered that understanding the present demands an inquiry into modern history. I have taken the opportunity to research the past—not just the revolutionaries of 2011, but those of 1952; and not just recent wars and conflicts, but the crisis of 1967, the so-called redemption of ’73 and the peace treaty of ’79; and many other lesser-known nodes on the timeline.

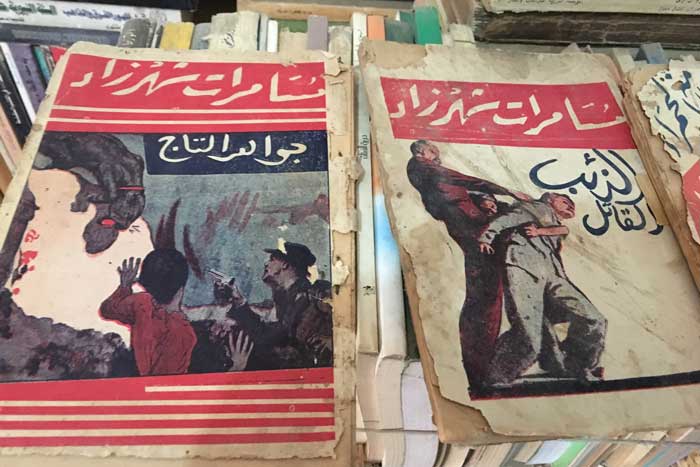

The most recent example has been a series of conversations I have had with the pioneering Egyptian novelist Sonallah Ibrahim, who at 79 continues to write and display a sharp wit. Our discussion about Egypt 50 years after the Six-Day War is available in the Spring issue of the Cairo Review of Global Affairs.4 On a lighter note, Ibrahim also told me that the ancient Egyptians were the first people in history to go on strike—for beer. What didn’t make into the published transcript were our chats about crime novels and noir in Egypt. I had brought several vintage Arabic pulp novels to spark the discussion, and Ibrahim asked if he could keep them. (I let him have one, but I need the rest for my research!)

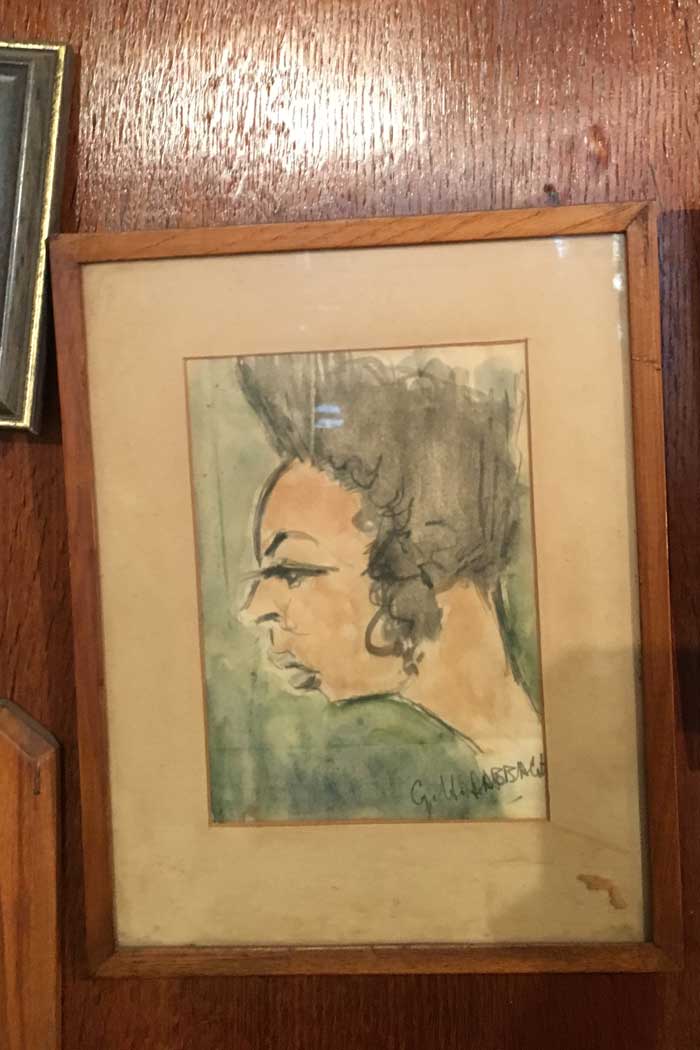

Indeed, being a researcher in Egypt is a lot like being a detective, and, incredibly, I’ve uncovered bits of lost history by coincidence as I rambled through Cairo’s used book stalls and antiquarians. My favorite is a caricature by the famous early modernist George Sabbagh (1887-1951). It is a simple yet elegant drawing of Josephine Baker. The seemingly back-of-a-napkin sketch captures her beauty in the way that only cartoons can. After some digging around, I learned that Baker had entertained Allied troops in 1943 at Cairo’s famed Shepherd’s Hotel—where I like to imagine Sabbagh might have heard her serenading.5

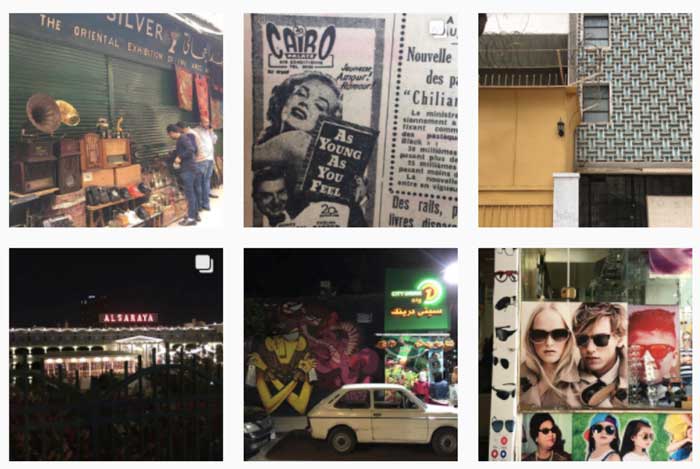

That fits into a leitmotif of my work, which has been the reconsideration of Egyptian modernity and Cairo’s connections to Europe and North America, a topic that is gaining traction in academic circles. Two recent exhibitions on Egyptian artists who dabbled in surrealism provide another example of a new history of Arab modernism and modernity that is finally being written.6

While exploring Egypt’s recent past, I often stumbled upon a comrade-in-arms: George Antonius (1891-1941), the first ICWA fellow in the Middle East. Antonius’s newsletters would serve as the foundation of his definitive text on the Arab nationalist movements of the interwar period, The Arab Awakening. Less well known is that Antonius was married to the sister of Amy Nimr, one of Egypt’s most famous surrealists; E.M. Forster acknowledged him as a singular tour guide in his Alexandria: A History and a Guide, which I used when exploring the Mediterranean city. As I dug deeply in the region, I seemed to keep crossing paths with Antonius.

There was something comforting about knowing that 90 years ago, he had sent his newsletters to Mr. Crane as telegrams.

Egypt tomorrow

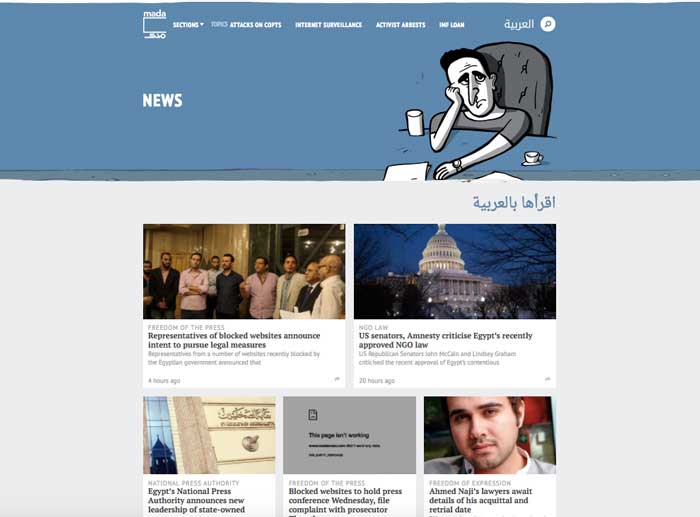

During my final week in Egypt, friends of mine gathered at the Windsor Hotel, a colonial watering hole in downtown Cairo, to bid me farewell (for now). The mood was hardly celebratory. Everyone was talking about the mysterious censorship of Mada Masr, one of Egypt’s few independent news outlets.

The online publication, put out in English and Arabic, was launched under the shadow of the summer 2013 amid General Sisi’s coup against the Muslim Brotherhood. Since then, Mada Masr—which translates as “Egypt Scope”—has published thousands of articles from hard-hitting investigations into the security services to useful cultural calendars, op-eds on every topic you can imagine and some of the funniest cartoons around. I, too, have written a couple of articles for Mada—one on the first annual Cairo Comix Festival and another about a children’s play I attended by accident.7 More to the point, I rely on it for daily news and research.

But in late May, when I tried to access Mada from my computer in Cairo, all I could see was a blank page. I later learned that the Egyptian authorities were blocking 21 websites. Many of them were affiliated with Muslim Brotherhood activists and some with Qatar, both entities seen as threats to Egypt’s status quo. But Mada is far from being Brotherhood—it’s secular, critical and independent, and certainly has no relationship to Qatar. Although sometimes unpolished or not exactly slickly edited—as any English language publication abroad might be—Mada is essential reading. And now it’s inaccessible to those who need it most.

Mada Masr’s cartoonist, Andeel, showed up late to my going-away party along with his colleague from a mainstream privately owned paper. The latter was planning a cartoon about Mada’s debacle. There were jokes and jabs, but everyone was relatively somber on this occasion. The question on everyone’s minds: Why were the 21 websites blocked? Why was Mada included?

It’s difficult to find logic in an autocracy—the kind of state where the authorities can act with impunity, parliament is toothless and state agencies are independent only insofar as they operate in the shadows, free from oversight. And although Mada has come back online through some internet service providers and 3G networks, it remains blocked on others—a telltale sign of inconsistency.

According to a security source quoted in many news stories, Mada and the other websites were “blocked inside Egypt for having content that supports terrorism and extremism as well as publishing lies.” Publishing lies, spreading falsehoods—a charge better known today as “Fake News.”

Although Fake News has become a tiresome buzzword in the United States over the past six months, the concept has never been a laughing matter in Egypt. Countless journalists have been held or charged over the ever-vague charge of “broadcasting false news with the aim of spreading chaos.” It’s an unfortunate catchall that has ensnared many.

A few days later, the authorities added a financial newspaper in Cairo to their list of blocked websites—for sharing false news. (Dozens of other websites have been blocked inside Egypt since then.) An Al-Jazeera journalist was detained as recently as December for the same alleged offense. Earlier this year, the country’s top corruption watchdog, Hisham Geneina, was charged with sharing fake information. Let me emphasize: in Egypt, Fake News is not simply a buzzword bandied around to score political points; it’s a serious charge that can ruin careers and result in prison sentences.

And yet the story of Mada Masr’s censorship, and so many other significant stories, scarcely cross the Mediterranean, let alone the Atlantic. The threshold for a news story in Egypt is too high, with the steady stream of terrorism and conflict—the unmitigated attacks on Egypt’s Coptic Christian minority, the relentless march of Islamic State-affiliated groups in the Sinai and the more attention-grabbing news happening in Egypt’s neighboring countries.

But blocking Mada Masr—and the questions so many friends and colleagues faced in the wake of that censorship—have had a chilling effect on free speech, expression and the press. There is no question that when the Egyptian authorities block a news site and call it false news, they are engaging is a frightening sort of intimidation. To share or spread “false news” in Egypt is tantamount to abetting terrorism.

Nevertheless, Mada Masr has continued to report, write and publish. Most inside Egypt can read only the latest articles on Facebook, where editors reproduce them in full. The Egyptian authorities’ attempt at censorship has become a game of whack-a-mole, and for now the independent journalists at Mada courageously continue to do their jobs.

The story of Mada Masr goes to the heart of how difficult it is to do original reporting in Egypt, where the stakes have never been higher in the face of resurgent autocracy. It is no coincidence that so many websites in Egypt were blocked, or that a new draconian human rights law was enacted a week after Sisi met with President Donald Trump in Saudi Arabia—not exactly a bastion of free speech. For now, it seems that Trump’s purportedly close relationship to Sisi has emboldened Egypt’s military government to advance its crackdown on civil society. And as the State Department, following the Trump administration’s lead, tones down its criticism in official statements and moves human rights advocacy to the quieter forum of bilateral diplomacy, Egyptian journalists will continue to come under attack.

That is the reality of the region today, and any analyst’s forecast would suggest more repression and regression, regime maintenance and dynastic succession—the very things young people rebelled against in 2011. It’s not that the fervor of the revolution is gone. It’s that public squares have been choked and dissent has migrated elsewhere.

While I can leave Egypt and return to the US, many of the journalists in Egypt have little option but to continue doing what they do. The fact that they do it with a sense of humor and panache is no small feat.

- This is a taste of a report I republished on the eve of Sisi’s election: “Picturing Egypt’s Next President,” The New Yorker, 22 May 2014. Available Online: http://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/picturing-egypts-next-president

- “Inside the Strange Saga of a Cairo Novelist Imprisoned for Obscenity,” Rolling Stone, 24 February 2017. Available online: http://www.rollingstone.com/culture/features/cairo-novelist-imprisoned-for-obscenity-in-egypt-tells-story-w468084

- “Writer Ahmed Naji prevented from leaving Egypt,” Mada Masr, 6 July 2017. Available online : https://www.madamasr.com/en/2017/07/06/news/culture/writer-ahmed-naji-prevented-from-leaving-egypt/

- “Plight of an Arab Intellectual,” Cairo Review of Global Affairs, Spring 2017. Available online: https://www.thecairoreview.com/q-a/plight-of-an-arab-intellectual/

- I first blogged about this last year: “La Sirène d’Egypte,” Oum Cartoon, 4 December 2016. Available online: http://oumcartoon.tumblr.com/post/154055952476/josephine-baker-in-cairo-by-georges-sabbagh

- See, for instance, my review of these two shows, co-authored with Surti Singh: “The Double Game of Egyptian Surrealism: How to Curate a Revolutionary Movement,” Los Angeles Review of Books, 17 April 2017. Available online: https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/the-double-game-of-egyptian-surrealism-how-to-curate-a-revolutionary-movement/

- See: “CairoComix: Excavating the political,” Mada Masr, 12 October 2015. Available online https://www.madamasr.com/en/2015/10/12/feature/culture/cairocomix-excavating-the-political/ “Art attacks! The extraterrestrial experience of The Gifted Painter,” Mada Masr, 20 September 2015. https://www.madamasr.com/en/2015/09/20/feature/culture/art-attacks-the-extraterrestrial-experience-of-the-gifted-painter/