TBILISI — Russian gas flows south through a pipe underneath the Caucasus Mountains to a hillside village near the Georgian capital where it heats homes including a run-down house used as a shelter by Russian activists in exile. Lack of insulation means most of the warmth has been escaping; the task for this December afternoon is to fortify this skeleton of a home so it can be habitable for winter. Packs of stray dogs stalk the barren fields and dirt roads of the sparsely populated settlement, where locals rely on each other trading goods and services.

With drills, hammers and mineral wool purchased at a roadside shop through funds from a Goethe Institute grant, the four activists from St. Petersburg—who identify as left-leaning and asked to remain anonymous—get to work. They toil efficiently in accordance with the anarchist principle of “horizontal organization”; no one barks orders and everyone knows their roles.

Within seven hours, the house is fully insulated. As night falls on the snow-swept village, the activists sit in warmth by a masonry stove, slurping pumpkin soup and nibbling garlic cloves. The space is now fully equipped to shelter activists and mobilization deserters expected to arrive in the coming months, albeit heated with gas from the country they fled.

The four members of this “countryside hub” are among hundreds of Russian opposition activists of various political leanings who have fled their country to Georgia throughout the past year. Some left in the months prior to Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine last February as repression grew to unprecedented levels in the Putin era. Others came after the war began, realizing that with their dissenting opinions, they could no longer live in what they deem a fascist totalitarian state.

In Tbilisi, they have created or joined new anti-war resistance organizations, which operate on Western grants and employ hundreds of volunteers. Working around the clock, these groups offer services in real time to Ukrainians refugees as well as Russian activists and military deserters fleeing their respective countries. The help comes in the form of evacuation routes, therapeutic services, legal guidance, shelters and resettlement plans.

Russians’ ability to directly challenge President Vladimir Putin’s regime remains limited from abroad. While they understand their immediate needs and tasks, a sense of how the war will end, whether the regime will collapse and what lies in store for the future remains murky. Disunity also persists, as activists disagree about how Russians need to behave and where efforts must be focused. Any leader to reconcile such differences has yet to emerge.

Fleeing Russia

When she entered politics in 2019, Irina “Irma” Fatyanova made a promise to her parents. A maximum risk of a five-year prison sentence would be her threshold for quitting. If she were to be threatened with anything more, she would pack her bags and leave the country. So in the fall of 2021, when the Russian authorities slapped her former colleague from the opposition leader Alexei Navalny’s organization with a 10-year prison sentence, she kept her word and fled to Georgia.

Since March, she has worked as head fundraiser for an organization that evacuates refugees from Ukraine. She asked that the organization not be named out of concern that highlighting the involvement of Russian nationals may raise suspicions among Ukrainian donors and refugees. “In any case, media attention should be focused daily on the struggle of Ukrainians, not on ‘good Russians,’” she says.

I met Irma at a coffee shop in the upscale Vakke neighborhood one evening during a short break from her seemingly never-ending work. Her brown hair was frazzled and eyes appeared weary, the stains on her pullover sweater were a visual reminder that she hardly leaves her apartment. She drank one cup of coffee during the interview and ordered another to go.

“My friends tell me my body is 80 percent coffee instead of water,” she tells me.

Like her former colleague and current public face of the Navalny organization, Maria Pevchikh, Irma also holds an academic background in sociology. Before her foray into politics, she worked for an Israeli cultural center in St. Peterburg.

She ran her first political campaign in 2019 as an independent in a St. Petersburg municipal election, feeling an urge to apply her experience in fundraising and desire to galvanize and enlighten people to a new profession where she could make a tangible impact on her society. Although she failed to win, her campaign colleagues, impressed by her charisma, urged her to apply to work for Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK).

During her two years as chief of the group’s St. Petersburg regional campaign, she never had a chance to meet the now-imprisoned leader. Just a few months after she joined the campaign, he was poisoned, barely escaping to Germany with his life. When he made his triumphant return to Moscow in January 2021 following treatment in Berlin, Irma hoped to be among the hundreds of people at the airport to greet him. But her plans were cut short when she was detained before boarding a train to Moscow.

“I must be the only person in the campaign who doesn’t have a selfie with him,” she quips.

After the authorities deemed FBK an “extremist organization,” its members shuttered their many regional offices across the country and deleted social media accounts and chats. Some higher-profile members fled the country to evade facing long-term prison sentences.

But Irma stayed, determined to run again in upcoming municipal elections. She miraculously garnered enough signatures from residents to allow her campaign to move forward.

Her tears of joy and subsequent tears of sorrow when she was first allowed to participate in the elections but later forced out by the authorities were chronicled in an award-winning documentary produced by The Economist. Still, Irma has no regrets. The grassroots campaign she built, with hundreds of volunteers of all ages and backgrounds, and the thousands of residents who agreed to vote for her, convinced her that it was still possible to galvanize an otherwise politically demoralized public.

“Water sharpens the stone,” she tells me, using a Russian idiom for how small deeds can bring greater changes. “Even the election committee employees were curious to engage me in dialogue,” she adds. “Despite their prejudices, they were moved by my political literacy and competence.”

Putin’s repressive system ultimately had the final word determining Irma’s future. A few months after her departure, the authorities froze all the assets she left behind. She also formally owes the government 4 million rubles ($54,000) in legal fines, which she has no intention of paying.

“I have severed all ties with the country and have no plans to return until this regime collapses,” she says.

Like Irma, the human rights lawyer Anastasia Burakova also fled her hometown St. Petersburg a few months before the war. Her work for Open Russia, a pro-democracy organization founded by the exiled Russian oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky and deemed an undesirable organization by the authorities, put her at great risk in 2021.

“That year, the Russian government’s persecution of the opposition grew to levels I had never seen in my several years working as a human rights lawyer,” she tells me. To protect its employees, Open Russia ended its operations in the country in the spring of 2021. In July, one of its chief organizers, Andrei Pivovarov, was pulled off a plane and handed a four-year prison sentence for “carrying out the activities of an undesirable organization.”

Soon after, Russia’s Investigative Committee, the main investigative authority in the country, called Burakova in for an interrogation. “They continued to hint at the fact that I still have a way out from facing criminal charges; that they were not yet placing any restrictions on me, including departure,” she tells me. “I suspect they decided to give me more wiggle room because I am a woman.”

That November, she fled to Kyiv, and a few months later, after Russia invaded Ukraine, moved to Georgia. Here, she created the project Kovcheg, Russian for “ark,” which, powered by donations from Khodorkovsky, helps Russian nationals who do not agree with their regime’s actions flee their country.

I met Burakova and her and her husband, Egor Kuroptev, director of the Free Russia Foundation’s South Caucasus office, at their apartment in the hillside Tbilisi neighborhood of Vera. Their tires had just been slashed by a disgruntled local whose parking space they had been occupying for several weeks, so our meeting was short.

Burakova was dressed as if ready for court: in a button-down shirt with hair straightened. She described her forced emigration in a calm, almost robotic tone; the incident was just another number in the calculus of Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

From her volunteering as an election monitor in Russia’s 2011 elections to offering pro-bono legal support to activists arrested during protests in subsequent years, Burakova’s career followed a linear trajectory. Degrees in political science and law equipped her with the legal know-how to aid political opponents, and now exiles, over how to wrestle with and escape an authoritarian system that often invents new laws to persecute citizens. As of 2022, “discrediting the Russian army” is now an offense that has landed countless people in prison for sharing anti-war posts on social media.

Her intimate familiarity with Russia’s legal system gave her confidence she would notice red flags before they were raised.

Our target audience is those who were apolitical their whole lives. If we can raise their awareness now, with luck they will be equipped to make the right decisions once the current regime falls.

Free of “foreign agent” and “extremist” designations, the 35-year-old Moscow-born media manager Ilya Krasilshik did not flee Russia until March 2022, a few weeks into the invasion. He regularly tweets ironic complaints in all caps ruing the fact that he has yet to be designated a foreign agent, which has garnered him much criticism from his compatriots in exile.

Before the war, he produced a podcast about how to correctly spend money, financed by the major Russian Alfa Bank. Coupled with his former position as CEO at a popular Russian grocery delivery app, Yandex.Lavka, that facet of his biography further stains his reputation in the eyes of many fellow exiles who doubt his dedication to civil society.

Nevertheless, his ongoing project, Help Desk Media, has helped hundreds of Russians flee, and seek legal aid and therapeutic help.

I met him at a trendy Tbilisi coffee shop called They Said Books, where he zoomed up on a bright red vespa, sporting his usual outfit: black jeans, a black zip-up hoodie and gray Doc Martens. A sign on the door read, “You are more than welcome here if you agree that Putin is a war criminal and respect the sovereignty of peaceful nations.” In his high-pitched voice and erratic articulation, Krasilshik dished out tropes about Russians’ disposition toward authoritarian leadership and imperial greatness.

“I knew when the war started that as a public person, I couldn’t just sit still,” he tells me, attentively watching yolk from his poached egg ooze onto his toast.

Krasilshik’s parents belong to the Soviet-era Moscow intelligentsia, whose children attended prestigious gymnasiums and lived in spacious, Stalin-era apartments inside the capital’s Garden Ring highway circling the city center. He began his media career at the age of 21 as the editor-in-chief of the culture and lifestyle magazine Afisha.

Founded in 2008, the magazine was emblematic of a burgeoning urban millennial class that came of age under former President Dmitri Medvedev’s short tenure a decade ago. The days of communism and 1990s deprivation were now making way for a fresh, glittering generation of yuppies fixated on “lifestyle” and embracing an apolitical hedonism.

“Afisha was the first magazine of its kind to brand Moscow as a global, cosmopolitan city,” he tells me.

But in 2011, after the government began a brutal crackdown on dissent ahead of Putin’s return to the presidency, this generation had its first, blunt taste of his authoritarian ways. Krasilshik moved to Riga, Latvia in 2014, employing his media know-how to become the first publisher of Meduza, a new independent Russian news outlet that grew to unmatched prominence.

Many Russians saw Meduza’s staff as a cliquey bunch—hipster millennial journalists of the Putin era who were among the first to make exile seem trendy. But Riga felt too provincial for Krasilshik, who longs for Moscow’s dynamism.

In 2019, following personal disagreements with the editorial team, he announced he was leaving Meduza. He refrained from disclosing details, telling me that “now is not the time to talk about conflicts.” He also cited his desire to earn money, and fears that if he didn’t quit journalism then, he would “remain in it forever.”

Just a few hours after our meeting, the Russian authorities labeled Meduza an undesirable organization. Its activities in the country are now banned “under threat of felony prosecution” and any Russian citizen who shares links to the publication or donates can face legal risks.

Krasilshik joined the tech giant Yandex, built around the country’s most popular search engine, in 2019 partly motivated by the idea that invigorating Russian society with new technology could help modernize the sociopolitical fabric. That was a “mistake,” he says. “All the good things we built have been erased, so it’s all irrelevant now.”

A few weeks after Russia invaded Ukraine, he published an opinion piece in the The New York Times titled “Russians Must Accept the Truth. We Failed.” The text landed him in hot water with many opposition activists who were angry to be umbrellaed under the collective “we.”

“He was producing a podcast about making money while some of us were actively combatting the regime,” a Russian exile who asked to remain anonymous tells me. “Who the fuck is he to speak on our behalf?”

When I asked what motivated Krasilshik to write the piece, he offered an incoherent response, saying that he initially envisioned it under the title, “We [the critically-thinking Russian populace] are not at fault.”

“Then when I wrote that,” he says, “I thought to myself, ‘wait a minute, no, this isn’t right; everybody’s trying to deflect blame from each other, including Putin who says the war is NATO’s fault, maybe we’re all actually at fault.’”

Telegram activism and political literacy

While they may not have lended him nuanced language to ruminate about Russia’s collective complicity, the skills Krasilshik acquired in his few years heading a customer service project were integral for his creation of Help Desk Media.

Like many other activist initiatives created in the context of the war, it relies on Telegram Messenger as its primary instrument. A user can access an automated “Telegram bot,” which opens a conversation with “Hello! This is the Help Desk, we assist anyone who has suffered from the actions of the Russian government.”

In a process similar to online customer service chatbots, Help Desk’s bot offers users a variety of options including “psychological help,” “mobilization and the army,” “How can I defend myself from the government?” and “How can I help Ukrainians?”

After users choose a category, the bot asks them to elaborate their question before a human volunteer connects with them to refer other services. Help Desk representatives often send users to other activist organizations. In the case of legal queries, they are referred to Anastasia Burakova’s Kovcheg, while draft dodgers are advised to contact Idite Lesom, another Tbilisi-based Russian project that helps men evade mobilization.

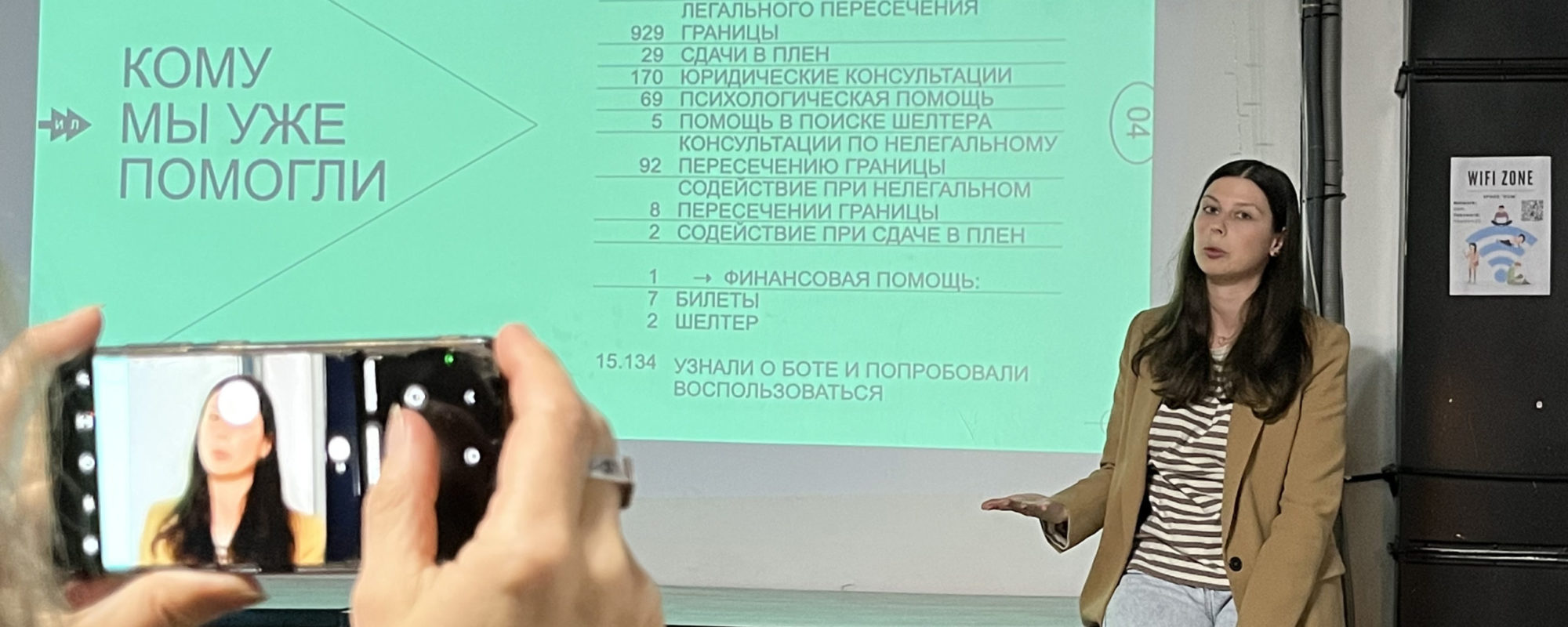

In a small apartment venue run by Russian activists bunkered on a steep cobblestoned hill in old Tbilisi, an audience of roughly 10 émigrés gathered to hear Darya Berg, a representative of Idite Lesom. The project’s name translates to “go by way of the forest,” an idiom used as a curse, similar to the English “to hell with you!”

Midway through her talk, Berg asked audience members if they would like to hear a story about a soldier who shot himself in the leg to get home from the frontlines. Laughter ensued, and the small crowd of seven uttered a resounding and sardonic “Yes!” “Oh, how horrible!” she responded with a sigh. The normalization of brutality, often through irony, has become a commonplace coping mechanism for Russians in exile.

Unlike Kovcheg and Help Desk, created shortly after the invasion to offer a wider range of aid, Idite Lesom was founded in response to Putin’s September mobilization order and focuses exclusively on helping draft-dodgers. It also utilizes Telegram bots for higher efficacy and to alleviate some of the burden from its roughly 300 volunteers. In easier cases, volunteers may educate men who receive draft notices about their right to avoid being sent to the front lines. Advice ranges from not opening doors to military recruiters, to avoiding showing up at recruitment centers.

In more dire scenarios, volunteers map out evacuation routes for soldiers who have already wound up on the front lines and chose to desert. “If our user asks whether he should choose between desertion or surrender [to the Ukrainian army], we will always say desert because we could still have some sort of control over this situation,” Berg told the crowd. “Our highest priority is men who are closest to the front lines.”

She also described how Idite Lesom’s volunteers refrain from dissuading mobilized alcoholics to drink themselves to states that would grant entry to rehab centers, or drug addicts to overdose on controlled substances. “Avoid the front lines at all costs, that’s our policy,” she said with a shrug.

Once they successfully help draft dodgers flee the country, volunteers from Idite Lesom often refer them to Kovcheg, whose own volunteers guide deserters to shelters and aid in legal integration to new homes, whether temporary or permanent.

Kovcheg currently operates shelters in four countries—Armenia, Poland, Turkey and Kazakhstan—and co-runs a shelter with the Georgia office of the Washington-based advocacy group Free Russia Foundation. “Beyond a roof under their heads, the shelters can function as places where people who weren’t previously politicized, such as mobilization deserters, can meet activists and gain political literacy,” Burakova tells me. “People often arrive in a state of extreme distress, and these shelters can help rejuvenate them and push them to move on with their lives.”

During a visit to Warsaw this month, I spoke to two Russian men who had met through Kovcheg’s shelter there and are now collaborating on political documentaries. Alexander, a 41-year-old filmmaker, tells me that Kovcheg “saved his life” when he arrived on a humanitarian visa with nothing but a suitcase and nowhere to sleep, just three days after the non-profit opened its facility.

As a public figure and son of a famous Soviet actress, he asked that I withhold his last name. Back in Moscow, his wife recently went on state television to complain that he had left her and their child behind to “self-actualize” in Europe, when in fact he had fled mobilization. It was part of a vitriolic propaganda smear campaign against those leaving the country, who are called “traitors” and “cowards.”

Beyond exiles and mobilization deserters, Kovcheg and Help Desk also actively try to reach people still in Russia, offering psychological help and pointing them toward clandestine regional bloggers whose materials are still accessible on Russian servers. It resembles a digital-era samizdat, the Soviet dissident practice of distributing banned works. “We understand that many people can have a variety of reasons for choosing to stay in Russia, and we do not want to pressure them,” Burakova says.

A 20-year-old museum intern in St. Petersburg may not have the funds or transferrable skills to earn money in a new country; a 40-year-old woman in central Saransk may not be able to leave the bedside of her ailing mother. “Such people may begin to go crazy if their entire families or social circles are brainwashed to support the war, and they begin to go crazy if they see pro-war imagery all over the streets,” Burakova says. “We want to let them know they aren’t alone.”

Russian government polls suggest most of the country supports the invasion of Ukraine, but Kovcheg and Help Desk operate under the assumption that many people in Russia remain in a state of confusion. “Our target audience are those who were apolitical their whole lives,” Burakova says. “If we can raise their awareness now, with luck they will be equipped to make the right decisions once the current regime falls.”

Those who support the war, according to the activists I spoke to, are a “lost cause.” Their reliance mainly on state television propaganda makes them impossible to reach. Both Egor Kuroptev of the Free Russia Foundation and Krasilshik tell me Russia is undergoing an internal “informational civil war.” While it continues, it will be impossible to reason with those who side with the enemy.

Kovcheg and Free Russia also see political rallies outside Russia as vital instruments for proliferating political literacy among Russians who fled mobilization. Kurpotev occasionally hosts anti-war rallies outside the Georgian parliament that often attract a few hundred Russian nationals.

However, some exiles have doubts about the efficacy of political rallies in countries where they arrive as foreigners. For the former Navalny aide Irma Fatyanova, the political slogan “No to war!” most often uttered at such rallies, appears especially problematic.

“I’m not ready to unite under a slogan that calls for immediate peace. For me, the end of the war means Ukraine’s unilateral victory over Russia, not an immediate ceasefire that could potentially be dictated by Russia’s terms,” she tells me. “That’s why all my efforts are focused on helping the Ukrainian side win the war.” Fatyanova believes there should be no ambiguity among activists in exile about how the war will end.

In the absence of leaders

During the question and answer session of a talk hosted by the Free Russia Foundation in which both Krasilshik and Burakova spoke about their respective projects, a debate erupted about the need for a single leader to guide Russia in the future. Daria Serenko, a renowned feminist activist and poet asked the two presenters to weigh in on the idea of horizontal organizing, citing her own collective, Feminist Anti-War Resistance Movement, as a successful example.

Burakova and Krasilshik were both dismissive. “Call me old fashioned but people unite around a single leader, this is how governments have existed for thousands of years,” Krasilshik responded.

He later criticized some of the more progressive, left-leaning organizations for entertaining standards he deemed too high at a time he believes a stable, proven mode of liberal governance is what Russia needs most. “They’re waiting for a knight in shining armor but they need to wake up, there’s a war going on.”

When I brought up the interaction between Serenko and Krasilshik to one of the four members of the leftist countryside hub, he commended her. “It was brave of her to come into a space where people operate in a binary way of thinking about Russia’s future and challenge their opinions, especially at such a sensitive time,” he said.

Despite their ideological differences, most of the activists I spoke to agreed that had Navalny been free, they would support him. They were even willing to shelve his earlier appearances at nationalist marches and claims that Crimea should belong to Russia. “Leftist opposition had all but dissolved in Russia in recent years, and if Navalny had managed to galvanize change it would at least give us the fertile ground to further proliferate our ideas,” the leftist activist told me.

Several exiled Russian politicians have tried to claim the mantle to brand themselves Russia’s future leaders since the start of the war. One such opposition figure, a young self-avowed Marxist named Ilya Ponomarev, organized a conference in Warsaw last November under the banner “The First Congress of People’s Deputies of Russia.” He was the sole member of Russia’s parliament to vote against the annexation of Crimea in 2014.

At the three-day event, which was disrupted by numerous disagreements and petty arguments about who had the right to speak, the exiled former lawmakers eventually got around to discussing what form Russia’s post-Putin constitution could take.

“To conduct these types of congresses and host mock parliamentary votes on Russia’s future while in exile just looks a bit cringe-ova,” Burakova tells me, using the popular English word that has been appropriated into the Russian language. Her husband Egor Kuroptev shares the sentiment.

“All those helping Ukrainians, who are leading the counter-propaganda efforts, who are undermining processes within Russia, who are ready to take responsibility for the war, and take responsibility for the anti-war movement—those are the leaders,” he says. “Maybe they aren’t currently recognized as leaders by the masses but that doesn’t matter, there’s a war going on.”

Top photo: Darya Berg giving a presentation about ‘Idite Lesom’