BERLIN — Jean-Michel Scherbak was on his way to a hospital in Moscow for surgery on February 24, 2022, when he received a text from his Russian mother that would define the course of their relationship.

That morning, on waking up to news of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the half-Guinean half-Russian model, actor and journalist had shared a post on Instagram expressing shock and dismay over his government’s decision to wage war. In the accompanying photograph, Jean-Michel, 31, tall and well-built figure with a gentle facial expression––once shown on the covers of Moscow’s fashion magazines––poses in Kyiv.

Rather than sending encouragement for his shoulder surgery, his mother lashed out.

“I congratulate you with the liquidation of weapons of mass destruction across the whole garbage-heap of Ukraine; the hour of reckoning will come when [Ukraine] will have to pay for the murdered children in Donbass,” her message began. “That’s what they get, those Banderite bitches!” she continued, calling Ukrainians by a pejorative Russian propagandists use, derived from the name of the World War II partisan leader and nationalist Stepan Bandera.

He then received what would be her last message before he entered the operating room: “Have a nice life; this is where we part ways.”

Three days later, he fled the country with his future husband, the prominent dissident journalist Mikhail Zygar. The government was drafting a law that would punish anyone speaking out against the war with a prison sentence, making it dangerous for those with the public exposure of Scherbak and Zygar, who is now labeled a “foreign agent,” to remain in the country. His mother wrote the same day, calling him a “traitor and a Russophobe.”

The messages continued to come in the following weeks, each more vitriolic than the last.

“As soon as they pass the law about the spread of bullshit against our government (I took a screenshot of your [anti-war] posts), I will be the first to report you to the authorities,” she wrote. “You are no son of mine; my family will have no traitors.”

Their communication soon ceased after Scherbak’s mother blocked him. They haven’t spoken to this day, although she occasionally takes to social media to slander her son publicly.

Although it’s an extreme case, Scherbak’s mother’s reaction to her son’s political stance is just one of countless examples of how the war has frayed relations between Russians who fled their country and close friends, mentors and loved ones who remain back home. With propaganda ramping up and access to information ever diminishing in Russia, many émigrés are finding it difficult to speak with those who stayed.

As the government continues to spew the narrative that it is fighting a “holy war” in defense of traditional family values, the increasingly abusive nature of personal conflicts reflects an already deeply damaged family institution in Russia, with extremely high rates of domestic abuse, child abandonment and divorce.

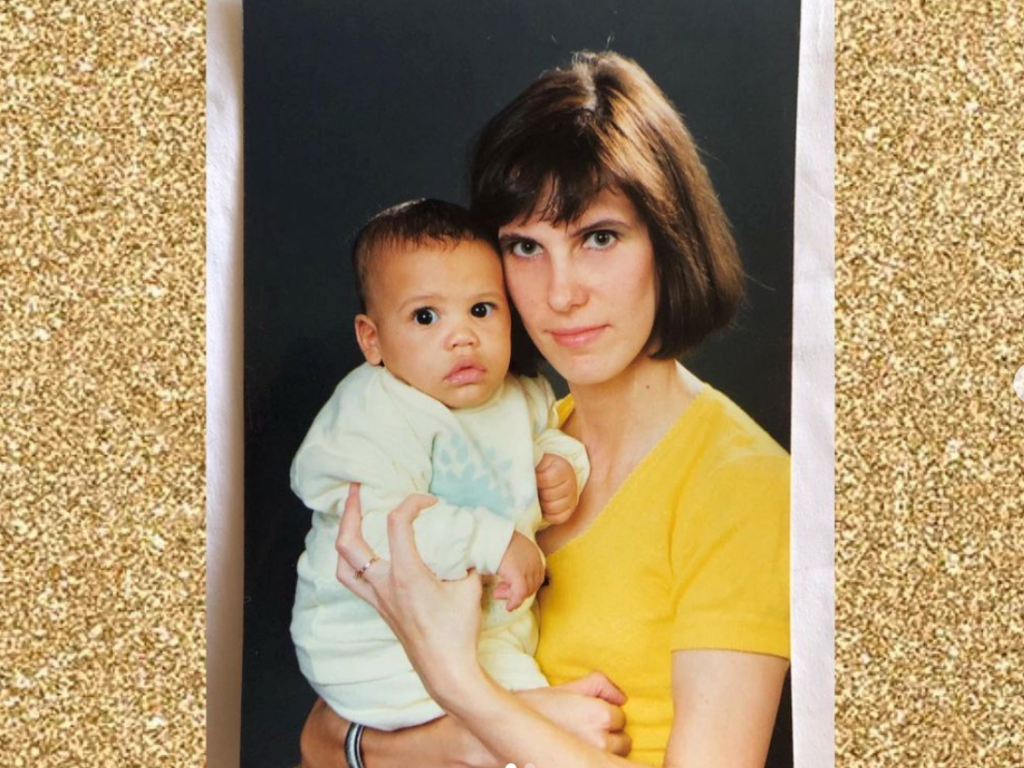

Scherbak spent much of his adolescence as an altar boy under the gaze of Orthodox saints depicted in the icons of Moscow’s centuries-old Sretensky Monastery. His father, who came to the Soviet Union in the 1980s as a student from Guinea, abandoned Scherbak and his mother shortly after his birth. Often teased about his African heritage to the point where he could not look at himself in the mirror, he said, Scherbak made sense of his struggles with the help of Russian Orthodox scripture.

A few weeks into Russia’s war with Ukraine, he turned to two confessors in a desperate bid to seek answers for the unfolding horrors.

The bishop Igumen John (Ludishchev), currently abbot of the Sretensky Monastery, responded to a WhatsApp message with a clip from a propaganda channel in which a scholar appropriates passages from Alexander Pushkin to justify Russia’s invasion. His second confessor, Tikhon Shevkunov, who was also once Vladimir Putin’s confessor, blocked Scherbak in response.

“I felt completely betrayed,” he told me over lunch in his apartment in a Berlin neighborhood he asked to not mention because of security concerns. “Everything I had believed in the last ten years discredited itself.” He now lives with his husband Zygar in the city that was once home to Russian writers, journalists and academics who fled their country’s civil war a hundred years ago.

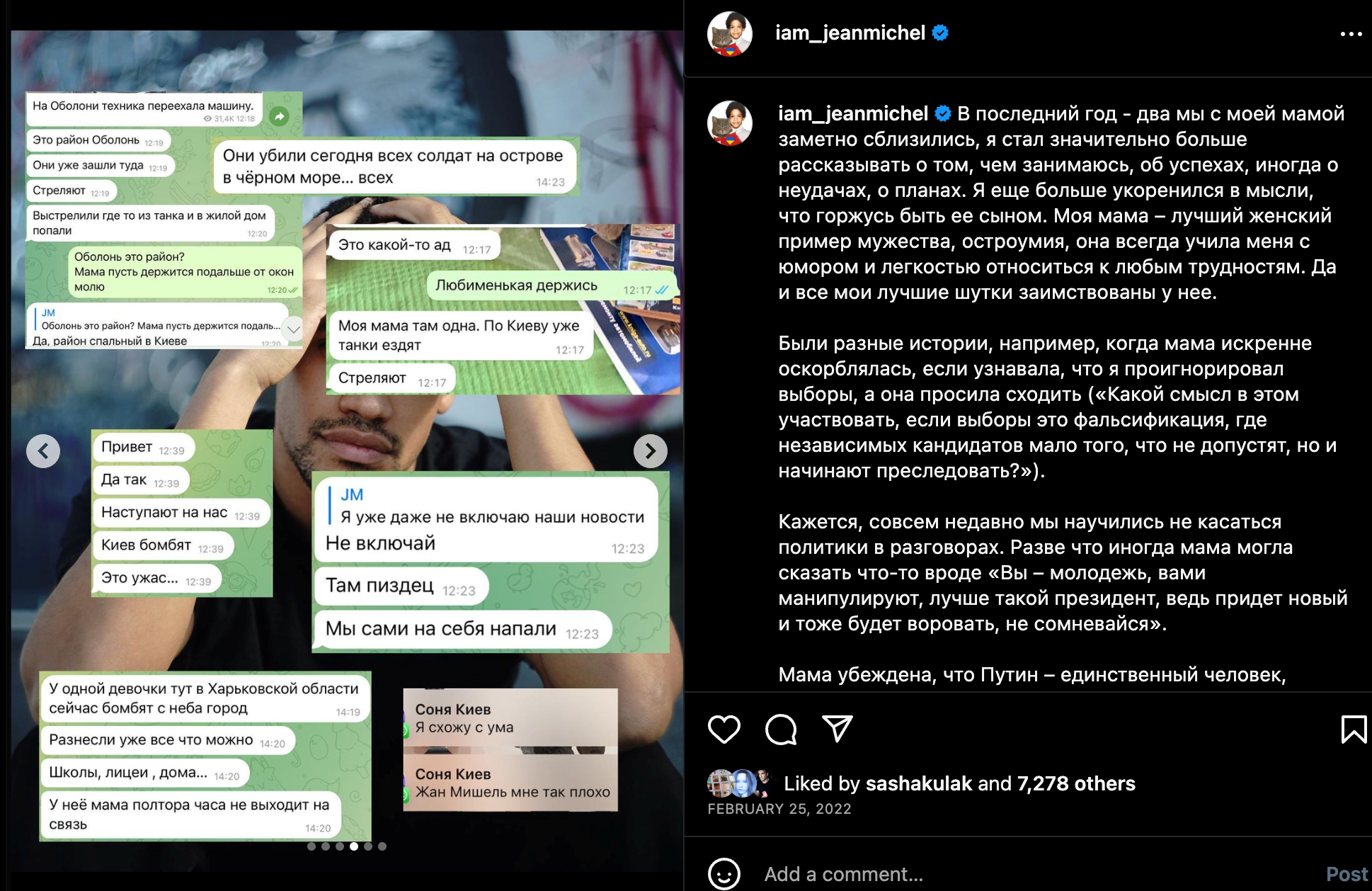

Immediately after the invasion, he started making posts on his Instagram juxtaposing his mother’s hateful messages with evidence of war crimes committed by the Russian army, clips of Kremlin propaganda and screenshots of messages from his Ukrainian contacts whose homes have been bombed.

He received a windfall of responses from Russians who were experiencing similar tensions, inspiring him to create a Telegram channel dubbed “Disowned by his mother.”

Now with several-thousand subscribers, the channel serves as a therapeutic forum where those who oppose the war share stories about the shock and horror they must reckon with when confronted by the contempt of their pro-war friends and relatives.

The family was no place for politics

Since the start of the war, sociologists and other experts have tried to understand what really lies behind public opinion surveys in Russia showing that 60 to 70 percent of the population “supports” the war. In trying to understand the logic of pro-war Russians, they hope to arm those who oppose the war with instruments and tactics to foster dialogue with those who support it.

In April, a small group of Russian exiles gathered in an apartment-turned-activist space on a wide Soviet-era boulevard in the Georgian capital Tbilisi to discuss how émigrés can broach difficult conversations about the war with relatives who remain in Russia.

Between screenings of Wes Anderson films and talks about gender fluidity, the organizers of “Community Space” hosted Andre Kammenshikov, a civil society activist with a Russian-American background who specializes in peacebuilding for the non-profit organization Nonviolence International to moderate the discussion.

He asked the participants, all millennial émigrés who had fled between the months of February and September 2022, to share examples of their attempts speaking with relatives. The idea was to parse through the conversations to come up with solutions for improving dialogue in the future. (I’ve altered the participants’ names for their security.)

One young woman, Masha, an eco-activist who had been living in Tbilisi for six months, told the group that while her parents opposed the war, her older brother, a tech worker, remained an ardent supporter. She recalled how he would blast videos in the family kitchen showing pro-Russian YouTubers celebrating Ukrainian deaths. Masha, who believes her brother is a lost cause, attributed his decision to support the war to his refusal to risk his successful career.

“People with more privileged backgrounds tend to actively support the war,” Oleg Zhuravlev, a Russian sociologist also now in exile, told me over a Zoom call. “If Russia loses the war, such people are convinced they themselves will have more to lose.”

The case of Shura, a young dog trainer from Moscow who left for Tbilisi in March 2022, aligns with Zhuravlev’s observations. Sipping coffee in a Tbilisi cafe, she described the “gobs of spit” that flew from her mother’s mouth when she recited Russian propaganda talking points about NATO enlargement and the decaying West. Shura’s grimace reflected palpable resentment.

She last saw her mother during a short visit to Moscow this past March, when her behavior seemed unrecognizable. Shura’s mother works as a dentist, a relatively well-paid profession. Shura is convinced her uncle, who works for the government and called Shura a traitor for leaving the country, played a part in “warping” her mother’s mind.

Besides zealous support for the war, many émigrés speak about relatives expressing resignation. Another participant of the discussion at Community Center, Aglaya, recalled a phone call with a female cousin who still lives near Lake Baikal in Russia’s far east. When Aglaya asked if she worried her husband would be conscripted to fight in Ukraine, she responded, “If he has to serve, he’ll serve.”

Such sentiments are common among working-class families in Russia’s provinces, moderator Kammenshikov said. “They perceive the war as if it’s a natural disaster, something outside their control they’re fated to reckon with.”

Sociologist Zhuravlev explains the tendency toward resignation by pointing to the “depoliticization of the society.” During the last decade of Putin’s rule, politics increasingly became limited to the elites, distant from the everyday lives of ordinary people who feel no agency over their country’s fate. As a result, the family “was rarely an institution of political socialization,” Zhuravlev said. “People were already unaccustomed to talk about politics, which made it more difficult to talk about the war.”

During the discussion in Tbilisi, a young man who works remotely for a Russian tech company described how his mother continued to work at Uralvagonzovod, Russia’s largest tank manufacturing facility found in the Urals Mountains city of Nizhny Tagil. “I assume if she still works there, she certainly doesn’t oppose the war,” he said, adding that he does “not have the spirit or strength” to broach the subject with her. Despite their political differences, they remain in close contact, their conversations often revolving around the mundane.

Nika Kostenko, an exiled Russian sociologist now based in Israel, says the tendency to tiptoe around the topic of war in conversations with relatives back home is a common trend among émigrés who seek to preserve their relationships. “Often, when a relative on one end of the line brings up the war, the other will respond with, ‘let’s not do this right now,’” she told me over a Zoom call. Kostenko, who conducts sociological surveys with other exiled colleagues about Russia’s wartime emigration for a project called Outrush, says that complete breakdowns in communication like Scherbak’s are not as common as may be expected.

From her sample size of 200 émigrés, a little over 50 percent retain close relations with parents and siblings back home. Indeed, many of my émigré contacts in Tbilisi have been visited by their parents who still lived in Russia throughout my several months there.

But not all such visits were welcomed.

The modern Russian family institution

Reclining on a park bench near a fountain on a spring afternoon, Asya, a 25-year-old Russian art school graduate who now works as a barista after leaving her country in September, told me how her mother tracked her down in Tbilisi to fetch her from Georgia.

“My mom is abusive, she would throw chairs at my sister and me, and when we grew older, threaten to report us to the police,” she said while a young Russian mother lovingly watched her two sons slurp ice cream on a nearby bench. Asya grew up in Syktyvkar, an industrial city in the vast and sparsely populated northern Komi Republic. “We would get only two months of light,” she said squinting under the hot Tbilisi sun. ”My class was full of children of prisoners and orphans.”

Domestic abuse was decriminalized in Russia in 2017, and the country ranks high on various global indexes. It has the third-highest divorce rate of any country in the world. Add an alarmingly high number of child abandonment cases, and the Russian state narrative that it is fighting to defend “family values” begins to appear hollow. The war in Ukraine and new wave of emigration have only amplified factors already undermining the family institution.

Asya had not been in regular contact with her mother for several years when she moved to Tbilisi. But after her mother discovered the coffee shop where Asya was working through Instagram, she barged in unannounced one afternoon.

Resorting to what Asya described as “familiar tactics,” her mother began threatening to report her to the Georgian authorities with the aim of getting her deported.

She did not know where in the city Asya lived, returning to the coffee shop for three days straight until Asya’s boss, a Georgian man who had lived in Moscow for many years, eventually intervened. He told Asya’s mother that her methods would not work in Georgia, that one could not simply bribe the authorities or file a criminal case without evidence. Asya’s mother did not appear the next day; Asya assumes she left the country.

Irreparable damage?

While Asya had sought to completely distance herself from her mother after leaving home for university several years ago, Scherbak had tried everything in his power to maintain a healthy relationship with his own mother before the war.

They would sometimes clash over politics. In 2020, his mother berated him for not voting for constitutional reforms that enabled Putin to stay in power longer. “You’ll regret this,” he recalls her saying. “I’ll be gone soon but you still have a future to live in this country.”

On New Year’s in 2022, they promised each other never to speak about politics again. When he was still hiding his sexual orientation, he also promised himself he would marry his female best friend to make his mother happy.

But the war forced him to break those promises.

In exile, Scherbak was able to marry his partner Zygar openly and legally. They married in Portugal in October after three years of hiding their relationship from the public. The marriage became a topic of ridicule on several Russian propaganda networks. Three days later, the Kremlin tightened an already draconian law on “gay propaganda.” The 2013 law ostensibly sought to shield children from exposure to “gay propaganda;” now any depiction or discussion of non-heterosexual in any public is penalized.

“I don’t think it’s a coincidence this amendment was drafted right after our marriage,” Scherbak told me.

Shortly after the wedding, Scherbak received another message from his mother, the first since she had blocked him in March. She congratulated him on his wedding with a clip of a Russian celebrity yelling the homophobic slur f***** on Russian state television.

At the talk in Tbilisi activist space, moderator Kammenshikov said the onus will be on Russian émigrés to maintain dialogue with their loved ones back home and gradually change their opinions to oppose the war.

“The major mistake is that we go in trying to reconvince them right away,” he said.

“But that never works. Instead, we need to plant little seeds of doubt in their minds so they can begin to question their own thinking.”.

Unlike with Soviet exiles who were forced to sever most ties with their homeland, Kammenshikov believes that modern technology is enabling the newest wave of émigrés to maintain channels of communication with relatives still in Russia.

Not Scherbak, however. “I’m afraid it’s over for my mother and me,” he says, although he hopes to help other Russians rekindle dialogue with their relatives with his Telegram group.

Leaving Russia has also inspired him to connect with his Black identity he had long suppressed. He couldn’t bear the sight of interracial couples when he was growing up, as they reminded him of his absent father, he said. But on a recent first visit to Washington, DC, he spent “hours and hours” in the National Museum of African American History and Culture unearthing stories about his heritage about which he previously knew nothing.

In one of his latest Instagram posts, he poses at a Beyonce concert in Hamburg sporting a see-through t-shirt lined with gold, along with Zygar, Zygar’s former wife and their daughter smiling in the background. It seems an image of a happy family––unhindered by the homophobia, militarism, repression and abuse left back in the homeland.

A week later, news from Russia emerged that medical clinics will soon employ so-called sexologists tasked with treating “mental disorders” including homosexuality. Even when entangled in a ruinous war with its closest neighboring country, the government makes time to wage its domestic offensive on what it perceives as threats to “traditional family values.”

“I was lucky to have my ‘cure’ be church and prayer, I never had to endure the indignity of being told that you are ‘ill’ and you need treatment,” Scherbak later told me. “I worry for the confused young children.”

Still, he added, a man in Russia wrote him to say that a video of him and Zygar on Instagram inspired his own coming out––a choice the man said his loved ones ultimately accepted. A lesbian couple who fled the country with their daughter to the Netherlands last year also thanked Scherbak for his public openness. He says he hopes his example will continue to encourage such stories despite the odds.

Top photo: Jean-Michel Scherbak in Berlin, wearing a sweater with the Ukrainian trident in LGBTQ colors