TBILISI — Kate NV played her last concert in Russia a few months after her country’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

The performance, in a Moscow nightclub named Mutabor—then still a hub for the city’s avant-garde music scene—was a fundraiser for an independent human rights organization. Despite the good cause, her participation would cause problems.

Soon after, the organizers of a Dutch festival in which she was set to play the following summer politely informed her they were removing her from the lineup. Her offense: Performing in a country waging a brutal military campaign against a civilian population.

Another night, in December 2023, Mutabor hosted a very different kind of event. A crop of Moscow’s remaining celebrities crowded into the venue, removing fur coats and wool scarves to reveal lingerie and other scanty outfits. The soon-to-be scandalous Almost Naked party—featuring guests including the socialite and former presidential candidate Ksenia Sobchak and pop star Filipp Kirkorov, whose garish performances are annually aired on state television—did not pass unnoticed by the authorities.

The organizers were soon forced to pay fines and attendees aired public apologies. Their offense: Attending a debauched party that verged on “the promotion of LGBTQ+ values” at a time when “our boys” were fighting a war across the border supposedly to protect Russian lives.

The episode illustrated the impact the war has had on Russia’s music industry. A venue that once nurtured the city’s major indie talents had become a space for a lowbrow event attended by many who publicly support the aggression against Ukraine and profit from the wartime economy.

It was a big change from the years leading up to the war, when the indie scene—like many of the country’s other creative arenas—experienced something of a golden age, its participants eclipsing globally recognized Western artists in popularity among a new generation of Russian listeners.

But the invasion of Ukraine and new censorship laws that followed pushed many well-known, free-thinking musical artists like Kate NV, real name Katerina Shilonosova, out of the country, leaving a noticeable creativity void. Although they can now express themselves freely outside Russia, some emigre musicians are struggling to navigate a fraught sociopolitical climate in which promoters hesitate to platform Russian bands against the backdrop of the war.

Shilonosova, who had already gained a Western audience before the invasion, overcame her setback with the Dutch festival, releasing an album and donating the proceeds to Helping to Leave—a charity that aids Ukrainians evacuating conflict zones—and performing at New York’s Lincoln Center in March.

But Western labels told the members of another popular band, SBP4, that any new associations with Russian acts while the war continued would be “toxic” despite their public denunciation of their country’s actions.

Aigel, a contemporary hip-hop duo that fled Russia in 2022, found a way around such obstacles. Aigel Gaisina, an indigenous Tatar who fronts the group, writes a large portion of songs in her native language. By repositioning themselves as a Tatar group, the musicians have been able to escape some of the limitations other acts from Russia face.

While they may struggle to find new audiences abroad, SBP4, Aigel, and Kate NV continue to perform for their traditional audiences, although they are a fraction of their size back home. Still, emigre-dominated audiences fill large venues in cities such as Tbilisi, Yerevan, Almaty, Belgrade and Berlin for concerts that serve as therapeutic reprieves from the struggles of emigration and unrelentingly bad news from home.

But none of those groups will be playing concerts back home anytime soon. They leave behind a realm that is becoming ever grayer, where any creativity that deviates from the jingoistic, conservative status quo invites repression.

Musical origins

Rock and roll kicked off late in Soviet Russia, gaining full momentum only in the 1980s under the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s policy of Glasnost, “openness,” when Western-style post-punk and hard rock bands were finally able to perform concerts, albeit under the KGB’s watchful eye.

Producer Ilya Baramiya, who was a part of SBP4’s original lineup and is now the mastermind behind Aigel’s dark production, lived through those times. Now 50, he doesn’t remember them fondly.

“I always felt negatively about the sovok,” he told me over Zoom from his new home in Montenegro, using a derogatory slang term for the Soviet Union and Soviet culture generally. “I aggressively resent people who lived through the USSR and are now embracing our current sociopolitical trends” of revanchism and militarism.

In conversation, Baramiya is acerbic and witty. With his receding hairline and flat nose, he could be taken for a tram conductor instead of a hip-hop production virtuoso.

He came to music without a formal education in the field, as a meloman, the Russian word for “music lover” which literally means “melody maniac.” His degree in mathematics from St. Petersburg’s prestigious Polytechnic University helped him master the modular synths and computer music programs making their way into his country.

Like Baramiya, his former bandmate Kirill Ivanov, 39, founded the iconic SBP4 (an abbreviation for the Russian phrase samoe bolshoe prostoe chislo, or “the largest prime number”) without a formal background in music. Born to a family of Leningrad intelligentsia, Ivanov was always a jack of all trades.

As a child, he danced at academies and studied Latin at a preparatory school before pursuing a medical degree while selling music equipment on the side. With his piercing blue eyes and a chiseled jawline, Ivanov could have easily added “model” to his diverse resume. Before completing his degree, he moved to Moscow to work as a correspondent for the flagship independent television channel NTV, covering the second Chechen war in the early 2000s.

But St. Petersburg’s glistening canals and creative vibrancy pulled him back and he returned to open a series of iconic music venues that played an integral role fostering an emerging “hipster class.” For many in the culture sector, the 2000s were a time of limitless opportunities. The freedoms of the impoverished 1990s were still felt, now accompanied by a booming economy.

Still emerging from its Soviet past, Russia was a cultural blank slate where strong demand developed for novel creative spaces amid the city’s generic sushi bars and hookah lounges.

Many critics now argue with hindsight that the “hipsterization” of Russia’s larger cities contributed to the depoliticization of the creative class. Rather than supporting civil society, the logic goes, intellectual energy was spent on entertainment.

Ivanov rejects that argument.

“Advancing culture and maintaining a political stance were not mutually exclusive,” he said, adding that his band recorded videos supporting the late opposition leader Alexei Navalny during his several arrests.

Before starting SBP4, Ivanov made music in his bedroom using cheap recording equipment and synthesizers. He would send tapes to his friends, who urged him to put his music online.

“I never really imagined I would be a musician playing concerts,” he said. Ivanov’s music reflects his nonlinear career trajectory; the percussive instrumentation is simple and naive but layered with poetic, spoken-word vocals.

While many of SBP4’s songs have a childlike tone, their 2022 album “Nothing Remains,” written before the full-scale invasion but released a few months after, is noticeably more somber. The song “Silence,” which muses about the dangers of collective passivity, feels especially prescient.

“I am the world’s most dangerous knife, without a handle or a point,” the lyrics say, “I am war and I am peace; silence is what they call me.”

Detsky Mir

In contrast to Barmiya and Ivanov, Shilonosova, 35, who fronted the technical, guitar-driven, art-punk band Glintshake—which once performed for Seattle’s KEXP radio—and now tours the world with her solo project Kate NV, learned to sing and play guitar and piano in a music-oriented primary school.

From the age of 12, she dreamed of moving to Moscow from her hometown Kazan, the capital of Russia’s Tatarstan Republic east of Moscow, after once getting lost in Detsky Mir—Children’s World, the iconic Soviet-era toy store—during a trip to the city with her father. In her live performances, she prances across the stage, her hair dyed bright pink or sky blue, singing songs that are light in mood but highly complex in their instrumentation. Echoes of the Soviet avant-garde collide with Japanese animation.

After earning an architecture degree in Kazan, Shilonosova made her move to the capital at 23. She would go on to co-found Glintshake with her then-boyfriend, taking inspiration from American bands such as Sonic Youth and the German krautrock movement.

“We were probably the only musicians in Moscow to make money exclusively from concerts and releases,” she told me with a chuckle outside a Russian emigre restaurant in Berlin. “We’d eat rice with onions and split chocolate bars.”

That evening, her hair was dyed a ghastly white that seemed to match her travel-weary state.

One benefit of being a popular rock outfit in Moscow during an economic boom was that commercial sponsors would offer musicians free clothing. Between 2016 and 2019, Shilonosova said, Nike Russia and other brands allocated good budgets for music festivals and concerts.

“It’s a fascinating story for a capitalist society because this really wouldn’t happen anywhere else,” she mused. “I can’t think of a single Western country where brands like Nike or Burberry would clothe punk musicians who play concerts for up to maybe 100 people.”

When she visited a music collective in New York City in 2015, the trip hammered home how privileged Moscow’s indie musicians were compared to their American counterparts.

“With hindsight, I realize what an abnormal situation it was,” she said. “Moscow’s indie scene felt like sparks emanating from electrical wires: beautiful, rich, but ready to explode at any moment.”

Stories from the penitentiary

Aigel Gaisina, 38, who used her name for the Aigel project she created with Baramiya, is also a native of Tatarstan. Unlike Shilonosova, her family is indigenous to the region. She was raised in the city of Naberezhnye Chelny by a “progressive” mother who made sure her daughter received a rounded education. Still, Gaisina’s traditional family pushed her to pursue a pragmatic education instead of her musical ambitions.

At age 18, while studying international relations at a state university in Tatarstan, she landed a summer internship at the State Duma, the lower house of the national parliament in Moscow.

“It was a very basic program where we’d just have to do menial paperwork and take photographs with people like [the late ultranationalist politician] Vladimir Zhirinovsky,” she explained over a Zoom call with Baramiya, her black hair parted down the middle.

That summer, she took part in a youth camp organized by the Eurasia Party, a nationalist/imperialist movement headed by the right-wing ideologue Alexander Dugin, whose ideas Western analysts frequently describe as “fascist.”

“There were orphans and other marginalized kids for whom Dugin served as a father figure, as well as members of [pro-Kremlin youth] movements,” she told the Russian journalist Yury Dud in an interview.

“For me, it was just about socializing and adventure. I really didn’t grasp what was what,” she added, revealing that a romantic interest had encouraged her to join the camp.

Later accepted into a doctoral program, she dropped out in her third year after giving birth to her first child. Her dissertation, on which she was working in 2008, was titled “The Imperial Myth of Contemporary Russia.” Back then, she was writing about “how Russia’s imperialistic tendencies were diminishing and the country was finally transforming to a normal nation-state,” she told me, chuckling over how much the tide has since turned.

While at university, she wrote poetry in her free time. One poem that led to Aigel’s 2016 hit “Tatarin” was based on her experience dating a man who had been unjustly imprisoned.

Like other songs on the project’s first album, “Tatarin” deals with her time confronting the penitentiary system: exchanging letters, waiting in long, wintry lines to deliver parcels to her partner in a remote colony, and writing countless appeals to the courts.

“These are songs told from the perspective of a poet who winds up in this low-life, prison world—the most marginal, the most extreme strata of society,” Aigel producer Baramiya added.

Baramiya and Gaisina did not meet in person until their first concert. Until then, their collaboration existed only online after Gaisina sent Baramiya demos of her music.

“While her production was sh*t, I immediately saw potential in her lyrics,” Baramiya said jokingly. “Russian music continues to be very lyric-centric, and [Gaisina]’s poems were ideal for the kind of recitative genre that was very popular among young Russian listeners.”

The harsh, dark undertones of the lyrical content initially put off potential promoters.

However, the eventual success of “Tatarin,” which now boasts 120 million views on YouTube, proved that “truthful, realistic stories remained appealing,” Baramiya said.

“It’s interesting to recall how such experiences felt so distant and incomprehensible to people from our creative indie social circles back in 2016,” Gaisina said. “Now, virtually everyone we know has been in a prison line, written letters to political prisoners or even served a sentence [on political charges]. These lyrics have become so relevant that the plight they describe no longer feels cruel. It’s become commonplace.”

Leaving Russia

Ivanov often wondered what went through the minds of Russians who emigrated after the 1917 Bolshevik coup. When Russia invaded Ukraine, he understood keenly that “this was exactly what they experienced.”

He told his bandmates they could longer continue making music or performing under the country’s new conditions and that “any acts of protest or free expression would be banned and punished.” Tapping into the SBP4’s collective savings, he budgeted funds for his bandmates to leave the country in comfort.

In Shilonosova’s case, the main obstacle to her leaving was her single mother, who begged her to stay. She couldn’t understand why her daughter would leave when the “country is in peril.”

“I told her that if she took a closer look at Russian history, she would notice the country always forced the best, most talented figures into exile before eventually rehabilitating and lauding them as heroes,” she said.

Countless other bands and musicians, including the band Mashina Vremeni and the highly decorated singer Alla Pugacheva—whose popularity in Russia perhaps eclipses even that of Elton John’s in Britain—and other Soviet-era icons also left the country.

A schism developed within Russia’s community of beloved older musicians, with many of those remaining pushed to participate in a patriotic flash mob called “We are staying!”

Aigel was among those who initially remained, mostly because Gaisina “egotistically” didn’t want to cause difficulties for her child. Baramiya also justified the duo’s hesitation saying they felt compelled to play for fans who were “scared and depressed” and to raise funds for human rights organizations.

Still, a suitcase Gaisina had packed the day after the invasion stood ready until she grabbed it a few months later to board a flight to Turkey. In September 2022, the musicians discovered they had been placed on a list of artists whose music was no longer “recommended” in Russia, effectively banning their live performances.

“Even if we hadn’t been banned, it had become insufferable to stay,” Baramiya said.

By August 2022, performers were required to sign documents promising they wouldn’t make political statements onstage.

“The musicians would agree to play a concert two months in advance, and just minutes before they were due onstage, organizers would shove this document in their faces,” Baramiya said.

The situation was “destroying us from within,” he added. “You can’t just passively sit through this. You either start to zigovat,” he said, using a slang term for the Nazi salute that is used to describe any acts of support for Putin’s regime, “or you are banned.”

Still, the duo refrains from passing judgment on musicians who stayed.

“Many have families, fewer resources, it’s difficult,” Gaisina said, echoing a sentiment I’ve been hearing from other emigres recently. If emotions at the start of the full-scale invasion compelled many to judge others harshly, two years down the line, many Russian emigres show more empathy.

A few hours before I spoke with Ivanov, I watched a documentary the socialite-journalist Sobchak, who had attended the Almost Naked party, had just released. In it, she follows the contemporary St. Petersburg art-rock outfit Shortparis to a remote Russian village. At one point in the three-hour film, the band members discuss the disconnect they feel with acquaintances who left the country, whom they accuse of “acting as if they’ve never lived in Russia.”

The musicians explain their desire to “remain with the people at a difficult time.” They play a show for locals of all ages, with abrasive operatic vocals, robust stage antics and all, before taking questions from the audience. When a woman criticizes their music’s “satanic elements,” local students defend them.

None of the issues plaguing Russian society—war, repression, propaganda, poverty—are mentioned in the conversation with the audience as it is shown in the film.

During the discussion, the Shortparis members make several references to a late Soviet-era television program called “Muzikalny Ring” (Musical Ring). The show featured rock bands performing, followed by Q&A “sparring” sessions. In the conversations, bedazzled audience members reflected on the nature of rock and roll aesthetics, which still seemed alien to many sheltered Soviets.

Shortparis’s references to the show made clear that they were effectively trying to recreate that atmosphere.

After the performance, the teenagers in attendance break out in a chorus of “Katyusha,” a Soviet-era patriotic war song, as the musicians revel backstage over how they inspired “dialogue” with their audience.

When I asked Ivanov what he thought of the act, he told me: “There is a time and a place for it—to ‘role-play’ as Soviet avant-garde musicians—which is not here and not now.”

“Shortparis is a very theatrical group, and in any different context, their act could be perceived as an interesting game,” he added. “But the war ended postmodernism in Russia. It’s no longer the time to do things with a wink or to remain vague.”

Back in Russia, Shortparis continues filling stadiums.

‘The pains of contemporary Russia’

Travelling between various cities where Russian émigrés now live means being able to attend performances of some of my favorite Russian musicians—from classics to whom I grew up listening with my father, like the Soviet-era Leningrad rock band Akvarium, to modern outfits such as SBP4. Against a backdrop of war and packed with audiences still grappling with exile, these concerts feel especially poignant and nostalgic. Many concertgoers walk out with tears in their eyes.

I saw SBP4 perform in Tbilisi less than 48 hours after the world had learned that Navalny had died in an Arctic prison in Russia. Ivanov took great care addressing the crowd of grieving Russians twice during the performance, acknowledging in a soft tone the collective pain everyone in the room was experiencing but also making sure to raise the daily horrors Ukrainians are suffering under missile barrages and other attacks.

Prior to the war, Ivanov told me, SBP4 never liked to banter with the crowd.

“The goal of our music was to create a mood, to take people to another place, and words spoken between songs often fracture this atmosphere,” he explained.

Now, Ivanov said, it “feels strange” to perform without speaking to the audience about the war or promoting organizations helping Ukrainians.

“It just can’t go unnoticed,” he said. “As a performer, you can’t not speak about the war.”

Gaisina agreed. When Aigel played in Tbilisi a few weeks after SBP4, she felt a “deep connection” with an audience exclusively comprised of Russian emigres who “laughed at my wry jokes and remarks about emigration.”

At a concert in Armenia’s capital, Yerevan, however, she noticed half the audience was locals, who she suspects came to hear her hit songs. She felt somewhat at a loss.

“I wasn’t sure which half of the audience to address,” she said. “Lately, when we perform for emigres, it feels a bit easier because we can find common ground, and a lot of our songs explore the pains of contemporary Russia.”

New audiences

The duo Aigel isn’t giving up on the idea of breaking into the Western market. Its hit song “Pyyala,” which Gaisina wrote in her native Tatar in 2019, has amassed more than 42 million views on YouTube, drawing interest from Western labels and distributors.

“We’re clearly doing something right if our songs garner tens of millions of views online,” Baramiya said.

Many Russian bands, including SBP4, have struggled to move beyond their traditional audiences since moving abroad. Especially in Europe, promoters hesitate to platform Russian artists for fear of backlash from pro-Ukraine voices. Some told Ivanov it was “toxic” to associate with Russian bands.

“But that’s okay,” he said. “We understand why and that we can’t do much about it right now. Hopefully things will change with time.”

As for Aigel, however, Gaisina’s Tatar roots and use of the language in her music have made it a more appealing prospect than an ethnic Russian band like SBP4.

She grew up in a “very traditional” Tatar family that consciously tried “not to mix” in marriage. Her grandparents insisted she speak only their native language with them. When Gaisina was in school, courses in Tatar were part of the mandatory curriculum across the republic.

In 2017, however, the Kremlin introduced a new law making Tatar language courses optional and limited to two hours a week, a move decried by Tatar activists as colonialist. Gaisina did not welcome the change.

“Not everyone has the time or resources for extracurriculars, and these limitations reduced the number of Tatar language and culture experts,” she said.

Still, Gaisina noted that among her generation, there is an impressive number of artists, designers, filmmakers and authors who actively work in Tatar. But she worries the school curriculum changes will have a detrimental impact on future generations.

“They need an infrastructure for learning the language, since a natural impetus doesn’t always come,” she said.

In Berlin, she discovered a group of people from Tatarstan that meets weekly to speak Tatar and discuss their culture. She also engages with indigenous activists from other Russian republics, a number of whom reside in the German capital.

“I understood from interacting with them that despite recent laws, Tatar maintains a privileged status,” she said. “Take an indigenous group like the Yukoghirs and you see their language is nearing extinction.” Tatar is still spoken by 7 million people globally.

A day after we met, Gaisina attended a three-day colloquium in Berlin dedicated to the creation of an AI machine based on the cultural memories of indigenous people.

“AI is currently modeled on Western-centric experiences and memories,” she said. “This new AI program will be based on the cultural codes and memories of indigenous peoples.”

Emigration has given Gaisina the opportunity to confront the challenges Tatars and other non-Russian ethnic groups face together with like-minded people. With her music, she is able to represent her indigenous culture as an ambassador to international audiences through a unique medium.

A return to Russia?

It was a sunny May afternoon in New York City. Shilonosova had just crossed the Williamsburg Bridge on a bike, casting off the depression and suicidal thoughts that had plagued her during the months she spent on friends’ couches in Belgrade. Still panting from the ride, she received a call from her stepmother informing her that her father had died of a heart attack in Russia.

“All of my happiness came crashing down,” she told me.

When I met her in Berlin in June 2023, just a few weeks later, she was disheveled, on her way back to Russia for the first time since she emigrated, to gather some of her father’s belongings.

She cleared her phone and social media of any political or war-related posts that might have caught the eye of border control officers.

Her visit to Moscow felt “strange,” she later told me.

“Many of the people I knew were gone, the very people that kept the city pulsating for me,” she said.

She continues to travel between New York City and Berlin and has yet to find a permanent residence.

Of Moscow, the only thing she misses is “just the aspect of having a home—I know I’ve aged by 10 years since I left,” she told me. “But it is what it is, such is the reality.”

When I asked Ivanov if he thinks about returning to Russia, he momentarily paused.

“It’s a distracting thought,” he said. “You can’t mentally be in both places. It’s very difficult for a person’s psyche. I realize now that I don’t miss that country, although I was a patriot of St. Petersburg.”

“F*ck no,” Baramiya said in response to the same question. “I buried that country.”

Gaisina, in contrast, holds out hope.

“Maybe not in the near future, but in 20 or 30 years, I’d like to return to Tatarstan in my old age,” she said.

In Berlin, she revels in no longer feeling as if she’s “being choked.”

“Transit strikes might ruin my commute,” she said of a common German occurrence. “But I don’t care! Please, keep protesting and striking. It’s exciting that people can loudly assert their rights!”

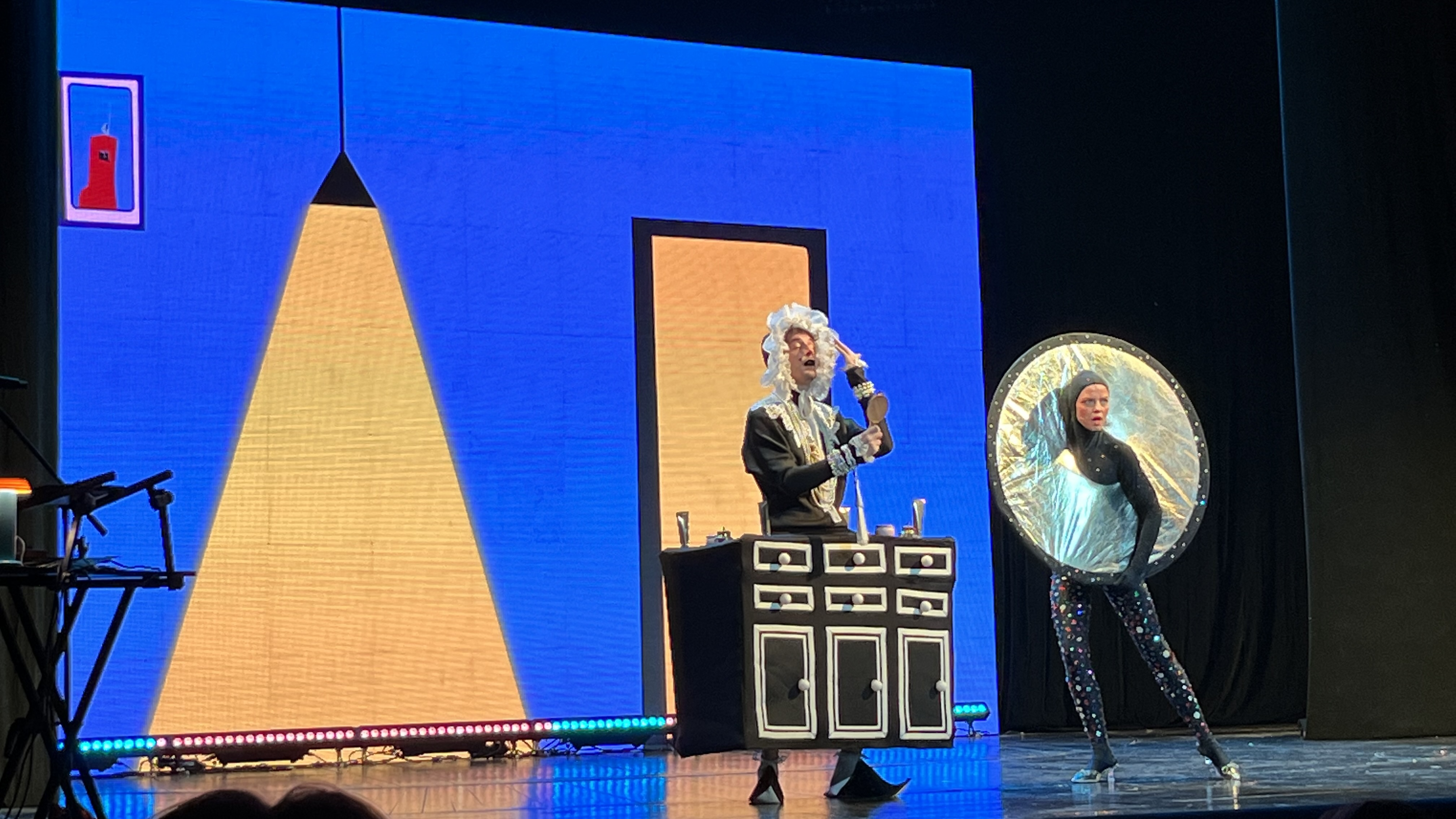

Top photo: Kate NV performing in Tbilisi