SAN JOSÉ LAS FLORES, El Salvador — “I’m not going to make any New Year’s resolutions or plans for 2020,” Alicia told me on New Year’s Eve as we sat on mismatched lawn chairs in her new backyard. “None of the plans I’ve made have ever worked,” my friend added. “Except for the plan to move here.”

She wondered if that decision was too daring. “But I was desperate,” she said. “I wanted the most radical change possible. And this was the most radical thing I could manage, short of leaving the country.”

A month earlier, Alicia had moved with her two sons, aged 11 and 13, from the home they had shared with her husband in the capital San Salvador to this small town in the far north of the country, in the province of Chalatenango, known locally as “Las Flores.”

As night fell around us and the drone of crickets threatened to drown out her voice, Alicia told me about all her prior plans that had fallen through. She had started thinking about migrating almost as soon as her children were born, she said, listing the countries she had considered: Russia, Switzerland, Italy, Belize.

When I asked whether she had ever thought about moving to the United States, she said it was complicated. Unlike many Salvadorans, she has no family network there, and the idea of crossing the border illegally terrifies her.

The crickets were soon joined by cohetes, loud firecrackers that seem to accompany every celebration in El Salvador but especially New Year’s Eve. We walked down a hill together to attend mass in the plaza’s whitewashed Catholic church, where the priest’s voice was nearly inaudible thanks to the explosions.

During the many conversations we have had in the six months I’ve known her, Alicia frequently pauses when talking about her choices and says, “Maybe that was my mistake.” It seems she’s trying to pinpoint where she went wrong, what she did to invite the structural hardships that made the life she had carved out for herself impossible. Her self-examination reminds me of what the anthropologist Ellen Moodie terms “the neoliberal sensibility of individual management of risk” — the conception of safety as a private rather than a political matter — which took the place of collective resistance after the war ended.

An estimated 285,000 Salvadorans are displaced each year, according to a recent Human Rights Watch report. Alicia and her family, who uprooted their lives because of poverty and insecurity but not due to an immediate threat, may or may not be included in such estimates.

In the United States, a key question in each asylum case is whether the asylum-seeker can reasonably relocate within his or her country of origin, making it unnecessary to seek refuge in a new country. I hoped to learn something from Alicia about the viability of internal relocation in El Salvador.

Trying to make ends meet

I met Alicia at church soon after my arrival in San Salvador last June. I stood out as a newcomer in the small, predominantly Salvadoran congregation, and she warmly welcomed me, telling me about all the activities in which she was involved that I could join. She gave me her phone number, offering help with anything I needed and invited me for coffee at her house. We became fast friends, and as I got to know her, she began to describe some of the struggles she was facing. Despite her gregarious demeanor and generous invitation, she was in crisis.

She had left her job as a university secretary in early 2016 with the understanding that she would have the option to return when she was ready. “Maybe that was my mistake, leaving my job, but they told me I could go back and my sons needed me at home.” She tried to return a year later, after unsuccessfully trying to find a part-time position that would allow her to work and care for her children, but “the door was slammed in my face.”

After over three years of unemployment, her job search was going nowhere. Her husband’s work as an industrial mechanic pays by each project, and not enough to cover the family’s expenses. Sometimes Alicia and the boys didn’t have enough money for the 25-cent bus fare to church and had to rely on a fellow parishioner for rides. As the school year neared its end, she feared she would not be able to continue paying her sons’ private school tuition, which was around $500 per year. (In El Salvador, the school year lasts from January to November, with “summer break” over the Christmas holiday.) When they got sick, she could not afford medicine.

Alicia’s decision to move was primarily driven by her economic circumstances; many of her worries are surely recognizable to mothers all over the world who want their children to enjoy good education, enriching activities and access to healthy food, medical care and spiritual formation. But security concerns were also never far from her mind.

Although sending her children to public school would have been more affordable, she considered it too dangerous. She had heard from other mothers about gang members who beat up their children or forced them to perform favors. She had decided to leave her job after one of her sons began acting out at school and a doctor warned that he was “a born criminal.” In a country where teenaged boys are targeted by gangs and stigmatized as possible gang members, that characterization terrified her and she felt she had no choice but to stay home.

I was desperate. I wanted the most radical change possible. And this was the most radical thing I could manage, short of leaving the country.

Last October, I casually mentioned that I was planning to drive to Las Flores to visit another friend, an artist whom Alicia had never met. That was when she told me her sister lived there; in an illustration of this hyperlinked society, I had unknowingly met Alicia’s sister on a previous visit when my artist friend and I ate lunch at the family’s restaurant.

Alicia asked if she and her sons could come with me on my next visit. She had always thought it might be nice to move to Las Flores someday, she said, but now the idea just clicked for her. It would be a safer place to raise her children. Alicia had never considered relocation viable because of the lack of employment opportunities in Las Flores, but she wasn’t able to find work in the city anyway and her husband’s income would go farther if he were to move back in with his parents and find a tenant for their house.

In Las Flores, we went together to scout out possible house rentals, and the first place we saw seemed just right. Located up the hill from the main square within walking distance of the school, it cost only $55 per month. The house is owned by a local who lives in the United States. His relative who showed it to us said the owner swore he’d be coming back in December, having finally saved enough money, but that Alicia shouldn’t worry. “He says that every year.”

A lifetime of displacement

Alicia experienced her first displacement in 1980, in the early months of the Salvadoran Civil War. Her family lived in a cantón, or rural district, near Suchitoto, a guerrilla stronghold in central El Salvador. Their community was completely destroyed during the war. The family had been driven from its home several times during air raids by the US-backed Salvadoran army, and in the middle of one of the attacks, her mother fled with six of her children and never went back.

Alicia was three years old, and her mother wrapped her in her apron to keep her warm while they hid in tatús, caves in the mountainside. The youngest child was only five days old, and Alicia’s mother wasn’t producing any milk to feed her so she kept crying. The baby was lucky to have survived, Alicia said: Some infants were smothered in similar circumstances when family members frantically tried to keep them quiet.

Somehow, the family made it to a refugee camp in Apulo, near Lake Ilopango, east of San Salvador. Alicia remembers orphans there crying for their parents. Alicia’s father and two older brothers, who had been out working in the field when the family fled, joined the resistance. Her father and oldest brother were killed in action and she never saw them again. (The other brother somehow made his way back to the family, deeply traumatized by his experiences.) Although Alicia tells me she has missed her father all her life, remembering the desperate cries of the children who had lost both their parents, she considers herself lucky.

The refugees in Apulo were tended by a Catholic priest named Fabian Amaya, who helped the family — which included Alicia’s mother and siblings and her mother’s sister and her children — rent a house in the town of Ilopango. Alicia’s aunt and cousins ended up refugees in Australia.

Alicia’s mother was able to buy a piece of donated land for a nominal price, and formed a new community called Santa Maria de la Esperanza together with other displaced families. They worked together to build houses as well as a school, church and community store. However, they lived in crushing poverty, relying on donations from the church for shoes, clothing and transportation. Her mother earned money by washing other people’s clothes in her home, but the proceeds weren’t enough to support her children or even pay off her tiny mortgage. Alicia finally did that as an adult years later.

Alicia came of age just after the signing of the Peace Accords in 1992, during the first years of democratic transition. She fought hard to find stability and finish her education. In the end, only one of her siblings graduated from college. Another brother committed suicide.

At age 17, she left high school to join a religious order, and lived with nuns in Guatemala, Mexico and then San Salvador. (“Maybe that was my mistake, not finishing high school the first time, but I didn’t even have enough money for bus fare to and from school. Maybe that was my mistake, not crossing the border to the US from Mexico when I had the chance, but I wasn’t thinking about migrating then. It just didn’t occur to me.”)

In her twenties, Alicia left the order and began attending an Anglican church. She went back to school and earned her bachillerato, the equivalent of a high school diploma. She completed a few years of college but never managed to graduate. After she married, she and her husband bought a house in a respectable suburb of San Salvador.

Adjusting to rural life

On New Year’s Eve, Alicia and her sons awoke around 3:00 in the morning to catch a ride from Las Flores into the city on the open bed of a milk truck. After leaving the boys with her in-laws to celebrate the holiday, she met me at the bus station and we started the long journey back to her new place. We took a bus from San Salvador to the provincial capital of Chalatenango, where we did some grocery shopping, visited the ATM and paid Alicia’s phone bill, none of which would be possible in Las Flores. Then we caught one of the infrequent buses to the village. We stood in the aisle of the packed Blue Bird school bus—imported from the United States—as it wound through curvy mountain roads for almost an hour before it deposited us at the entrance to Las Flores.

The lack of employment opportunities and infrastructure are not the only downsides to living in this part of El Salvador. Alicia still worries that her landlord will either decide to come back from the United States or be deported. She also worries about whether her sons will fit in and make friends. “Chalateco” humor is notoriously rough, involving name-calling and teasing, and Alicia’s boys are sensitive. There is only one public school in town, and public transportation is too unreliable for them to study elsewhere. If they are bullied or otherwise have trouble in school, there will be nowhere else for them to go. The options for religious worship are also limited: the nearest Anglican church is several hours away.

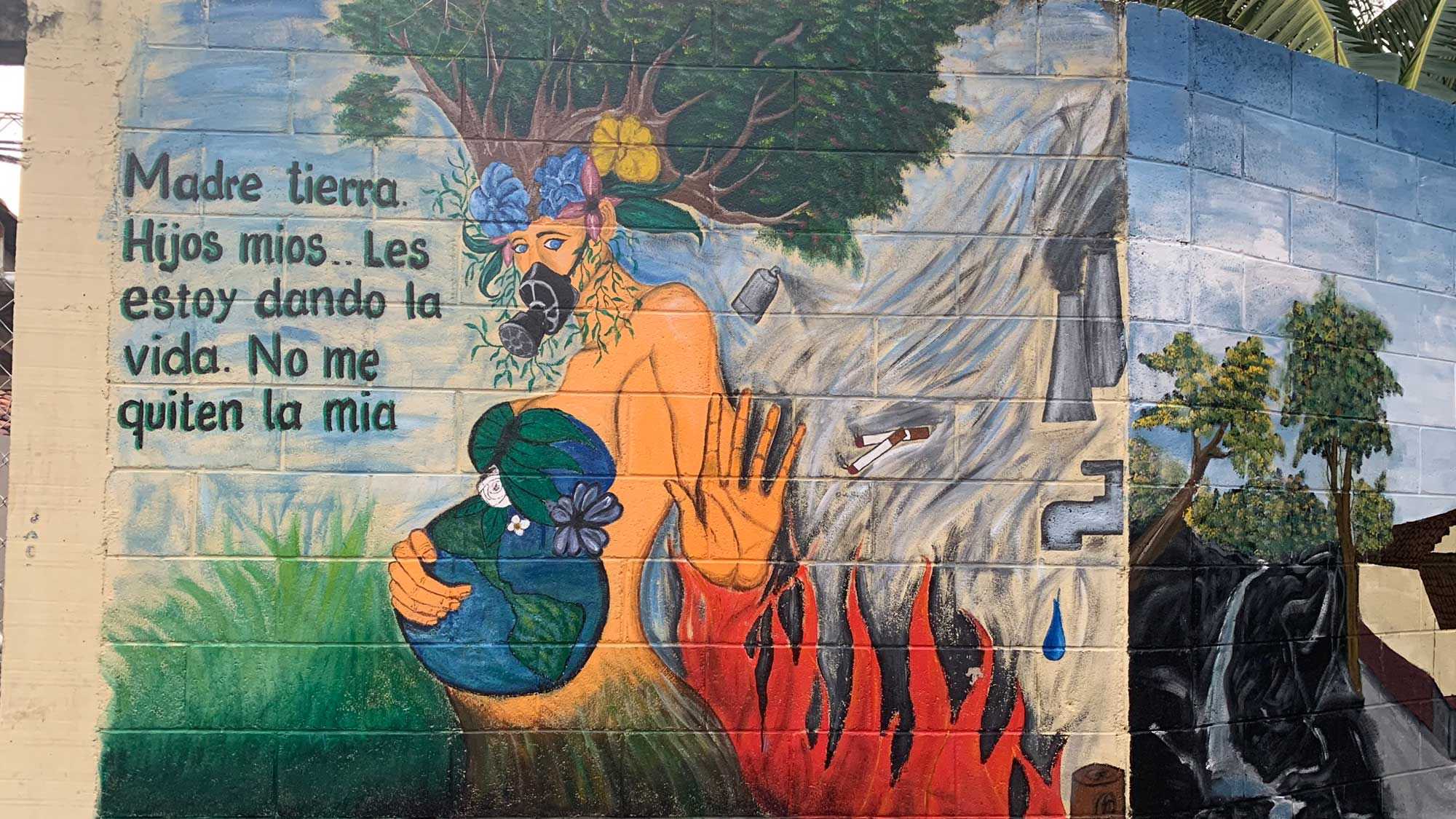

Throughout my visit, Alicia also fretted to anyone who would listen about expected water shortages. Access to water is a challenge across El Salvador, but particularly in this region. Prominent town murals proclaim: “Water is a human right!” Alicia has heard that during the “summer” months (approximately February through May), there will be running water for only two hours a day every other day, but even then she’s not sure it will reach her house. Without a car, she would have to walk all the way to the river to bathe and wash clothes. She brought that up in conversation with almost everyone we met, asking for advice or at least for information about what to expect and getting mostly non-committal responses agreeing that those are hard months.

Las Flores was destroyed during the Civil War, and its inhabitants fled across the border to refugee camps in Honduras. Not far from the town, in the Sumpul River where we went swimming on New Year’s Day, a notorious massacre took place when Salvadoran and Honduran troops fired on Salvadoran refugees trying to escape the violence. In 1986, some families from Las Flores returned and began to rebuild, organizing their community and redistributing the land. They are proud of their guerrilla heritage, and the town square is decorated with a bust of Che Guevara as well as a small display of weapons from the war.

This area is one of the few places where gangs have been unable to infiltrate. El Salvador is made up of 262 municipalities, all of which registered at least one homicide or sexual crime between 2013 and 2018, Human Rights Watch found based on government data. Las Flores is one of only three rural municipalities (each of which has a population of fewer than 2,600) in which no homicides were reported. Some say that’s because former combatants kill any suspected gang members who try to enter their communities. True or not, the town authorities do control who comes to live there. Alicia and her sons were able to move in only after being vouched for by her brother-in-law, Reyes.

When I met him, Reyes asked what I was doing in El Salvador and I explained I was writing about Alicia’s challenges in San Salvador and decision to move. “We have those challenges, too,” he told me.

“We are also, what’s the word, desplazados (displaced people). But we were displaced by the environment,” he said. His former home near Lake Ilopango experienced frequent landslides. After a hurricane, the family decided it wasn’t worth rebuilding and decided to sell the house. “This is where I grew up, so I talked to my sister who still lived here and she helped us find a place.”

A durable solution for the internally displaced

Stories like Alicia’s show that even without an imminent threat, relocation can seem like the safest option for families facing economic hardship combined with general security concerns. However, internal relocation is often a temporary solution prior to emigration. Family networks are most often comprised of individuals in similar economic situations, facing comparable hardships. With approximately 60,000 gang members reportedly operating in 247 of the country’s municipalities, the options for relocation are frequently limited to gang-controlled territories. And without existing family ties there, relocating to the few municipalities not under gang control is restricted.

Nongovernmental agencies have been fighting for years to pressure the government to recognize the problem of internal displacement. The country made some progress toward that in January, when the National Assembly passed new legislation regarding the protection of internally displaced people, but the law’s implementation remains ambiguous.

Alicia’s story is unusual—not because of the factors that led her to leave her home, but because she was able to voluntarily relocate to one of the few safer parts of El Salvador rather than the United States. Relocation within El Salvador may be a viable option for those with family connections in the right places (and without family connections in the United States) but is unlikely to be a lasting solution or one that is widely available.

Alicia’s sons will grow up and be forced to seek educational and employment opportunities outside Las Flores. Her husband is unlikely to find work there and will remain separated from the rest of the family in order to continue supporting them. Alicia herself would like to go back to work and school to finally finish her university degree. The future is uncertain, but for now, she’s focused on enjoying the beautiful scenery, settling in with her children and finding ways to get involved. She’s also looking forward to a time when she won’t be constantly thinking about what she should do, and hopes her bold move wasn’t a mistake.