Steven Butler is a former senior program consultant for the Committee to Protect Journalists. He previously served as CPJ’s Asia program coordinator. He lived and worked in Asia as a foreign correspondent for nearly 20 years and was a foreign editor at the Knight Ridder Washington Bureau. He holds a PhD in political science from Columbia University and a BA from Sarah Lawrence. Steve was fellow in South Korea from 1983 to 1986 researching economic and political developments in the region. He came back to the institute in 2007 to serve as executive director for seven years.

Steven Butler is a former senior program consultant for the Committee to Protect Journalists. He previously served as CPJ’s Asia program coordinator. He lived and worked in Asia as a foreign correspondent for nearly 20 years and was a foreign editor at the Knight Ridder Washington Bureau. He holds a PhD in political science from Columbia University and a BA from Sarah Lawrence. Steve was fellow in South Korea from 1983 to 1986 researching economic and political developments in the region. He came back to the institute in 2007 to serve as executive director for seven years.

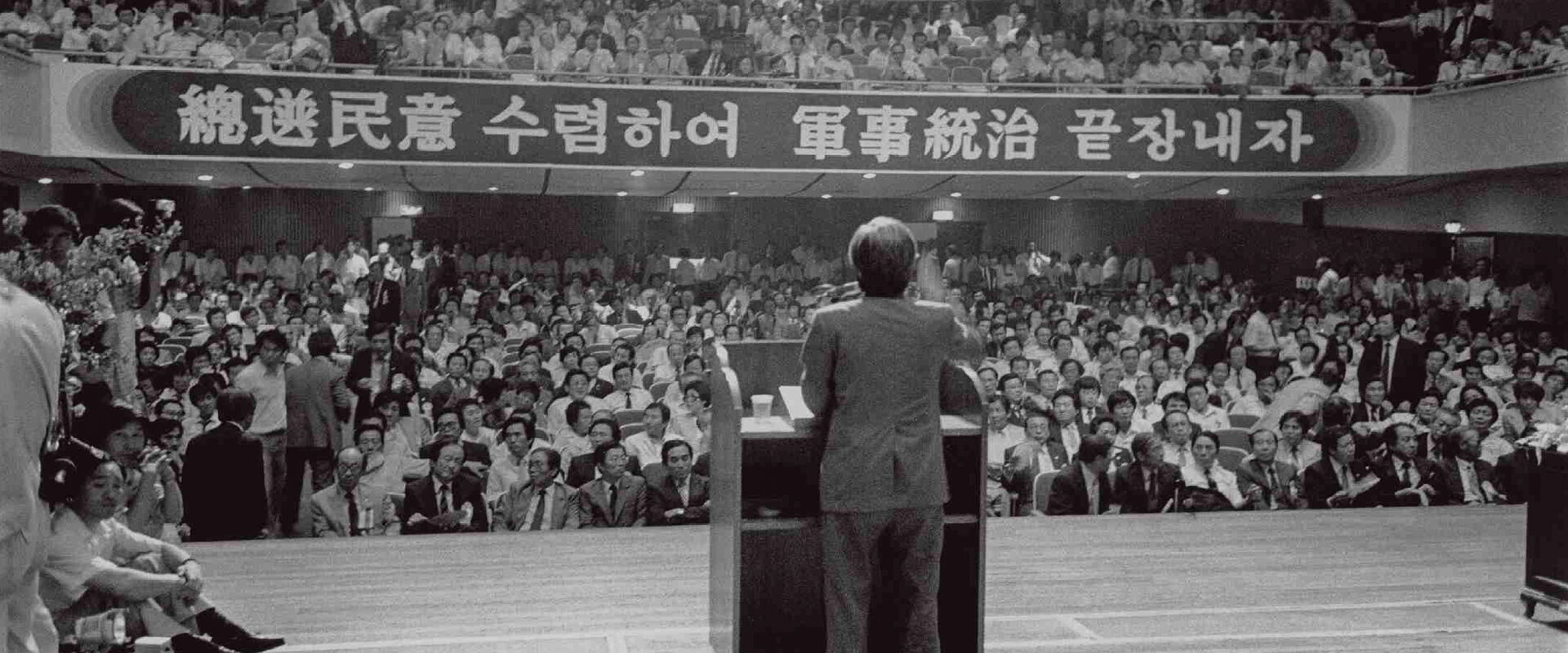

In 1980, Major General Chun Doo-Hwan came to power in South Korea through a coup d’état, declaring martial law and brutally suppressing a student-led democratization movement called the Gwangju Uprising. He inaugurated the Fifth Republic of Korea, a de facto military dictatorship and one-party state. In this excerpt, Steve describes the 1985 legislative election that brought the New Korean Democratic Party into the National Assembly as the main opposition party, seen as a rebuke to Chun, with voter turnout at 84.6 percent of eligible voters. The Fifth Republic came to an end 1988 amid widespread popular dissatisfaction that helped bring about the first peaceful transfer of power in South Korean history. The Sixth Republic has continued to the present day, although not without controversies including former President Yoon Suk-Yeol’s 2024 declaration of martial law and subsequent impeachment.

SEOUL (April 1985) — Something very important happened in Korea on February 12th. The Korean people went to the polls in record numbers and voted decisively for democracy.

They may not get it. But the vote has set in motion a process of change in which the opposition has begun to rally its forces against the government. The vote spells a complete defeat for the government’s political program, which it has pursued doggedly since the military coup that propelled President Chun Doo-hwan to power in 1980. And it leaves Korea’s near-term future in great uncertainty. The opposition is learning how to flex its muscles again. But it is faced with a smarter, if severely chastened, government that is determined to hang on to power…

… The government party officially maintains to this day that it is satisfied with the results. It received about the same percentage of the popular vote as last time and retained its majority of seats in the National Assembly handily. It even points with pride to the large representation in the National Assembly of the opposition, arguing that this just shows the voting was fair and that Korea has something far closer to democracy than any other Asian country except Japan.

But privately party members and government officials admit that the vote was a setback, a defeat for the government, and a popular rejection of the government’s political program. In fact, even though the Korean people did not—really could not—vote out the government, they did vote down the government’s main political goals. They voted into the Assembly precisely the politicians the government had worked so hard to destroy over the previous years.

What the voters rejected was the government’s idea that the opposition should play only by the government’s rules. It voted into the assembly a party whose only purpose is to revise the constitution, change the electoral system, get the military out of politics and, if it has the might, to put President Chun out of office as soon as it can. The opposition in the last Assembly was a policy opposition. It did debate vigorously over policy measures, but it played within the bounds of not questioning the premises of the system and not directly challenging the President. The new opposition intends precisely to enter these forbidden zones and put off consideration of all other policy questions. Their determination is bolstered by a firm belief that the Korean people broadly support them and they are not in a mood to compromise.

The issue is very simple: the opposition wants an electoral system—particularly for the President—that will allow them to translate their widespread popular support into a share of power, and they see constitutional revision as the principal means to accomplish that. The opposition firmly believes that the current system of indirect voting for the presidency will allow the military to engineer the election of another former general in 1988. It would also like to scrap the current electoral law for the National Assembly which has allowed the government party to win a majority of seats with far less than a majority of the popular vote.

The government appears intent on stonewalling. It says that political stability requires that the constitution go unchanged for at least the first presidential term. It says that peaceful transfer of power is more important than opening wide the floodgates of democracy; Korea has never had a peaceful transfer of the presidency. Privately, government officials and ruling-party members argue, with apparent candor, that the Korean people are not yet ready for full democracy because factionalism is intense and politicians too corrupt. The government appears intent on holding on to power and, right or wrong, ignoring the clear message of the election that the Korean people want democracy.

The election has, in the broadest sense, caused the political system to come full circle. Despite the government’s efforts to foster a multi-party system that diffused political conflict, the nation once again has a two-party system with the lines drawn more clearly than at any time in the past 25 years, The government failed to create a new center of political gravity with its manipulated opposition and now, as one diplomat put it, “All the elements are in place for a confrontation.”

The government clearly has been chastened by the experience. People who know President Chun say the election results were a great personal shock. He seems finally to have realized that he failed to sell his ideas on gradual political development to the Korean people and, worse, has failed utterly to convince the Korean people of his own legitimacy. He moved in a new leadership team to revamp the government’s public image, and now speaks of the need for dialogue with the opposition.

What is not clear is whether President Chun has the ability to move beyond dialogue to compromise.

The opposition too has yet to prove it can overcome its internal bickering, which is intense, or that it has gained the maturity and learned the political skills of challenging the government without frightening it and bringing the house down. Many Koreans are now openly fearful that the old historical sequence of liberalization, chaos and military intervention has begun once again.

Top photo: A New Korean Democratic Party convention in Seoul, 1985 (Wikimedia Commons)