SEOUL — When I arrived at the entrance of Gyeongbok High School in the city center on Nov. 15, the day of South Korea’s infamous college entrance examination, a group of parents was already waiting under the overhang of a nearby church. It had been raining all day and there were still hours to go before their children would exit the gates with the test finally behind them. Rather than chit-chatting to pass the time or sheltering in a nearby cafe, the relatives stood stiffly and silently apart under umbrellas and awnings, eyes fixed on the sloping hill leading up to the school.

The day of the 8-hour College Scholastic Ability Test—daehak suhak neungryeok shiheom, or suneung for short—is an event of national concern in the country, which unites to ensure it goes as smoothly and predictably as possible. Schools stage elaborate ceremonies to cheer on their students while politicians and celebrities release statements wishing them luck. Banks and stores close and police officers are out in force to control traffic and offer rides to late students. Ensuring silence during the listening portions of the test is paramount. Flights are grounded across the country to help students keep their focus, and this year, with its wet forecast, meteorologists rushed to reassure families there would be no thunder to worry about, either.

Despite all those efforts, this year’s suneung did come with uncertainties. In June, the government announced it would be removing so-called killer questions from the exam. Notoriously challenging, they are aimed at helping testers identify top students but often include concepts not taught in public schools. Therefore, test-takers seek out private classes and tutors to cover unknown ideas, a “vicious cycle” that encourages “excessive competition,” according to Education Minister Lee Ju-ho. However, the late change meant students were not entirely sure how to strategize for the test or how they would be graded.

Offered only once a year, the suneung is the culmination of more than a decade of labor and study for students in their third and final year of high school. The vast majority has been enrolled in specialized hagwons, or private academies, for hours of extra tutelage since the age of four or five. Older students spend the months or even years before the exam studying from morning to midnight, spending less than an hour on leisure activities on average and sleeping just five and a half hours a day, according to statistical analysis. Because suneung results play a significant role in college admissions, many students see taking the exam as the single most important moment of their young lives, a message hammered home by parents, teachers and society in general.

Successive government administrations, conservative and liberal alike, have attempted to reduce the pressure on students and relieve competition, responding to the widespread belief that the education system has collapsed. Critics of the current arrangement argue the inadequacy of public education curricula and the startling expense of private education exacerbates inequality, and that by prioritizing rote memorization over creativity and critical thinking, it produces citizens poorly suited to today’s economy.

Many also link the education system to the country’s mental health crisis. South Korea has the unfortunate reputation of having the highest suicide rate among OECD countries, and according to scholars Jingyi Xu and Sun Goo Lee, suicidal ideation rates are “astonishingly high” among high school and middle school students in particular. Xu and Lee also found that 9 to 14 percent of students who responded to a government survey suffered from general anxiety disorder, while 19 to 30 percent had depression. That is far above the rate of depression among adults, which is closer to 2 percent.

I remember feeling stressed out and overburdened as a high school student in the United States, but the stories I’ve heard in South Korea are on another level. Whereas I started thinking about college applications only once I had reached high school, South Korean students start preparing in preschool. Whereas as a child, I devoted whole weekends and summers to playing and exploring, many Koreans remember filling breaks with hagwon classes and self-study. And whereas I was eventually encouraged to cultivate non-academic interests in the arts and athletics, Korean students are often actively discouraged from doing so unless they plan to turn hobbies into careers.

Generally speaking, they are told there is only one path to success: acing the suneung, graduating from a top university—ideally one of the top three, Seoul National University, Korea University or Yonsei University—and getting a high-paying job, ideally as a doctor or at a prestigious conglomerate.

I don’t think I fully appreciated the effects of this burden until I was invited by David Tizzard, a commentator on Korean culture and society, to speak to a classful of young women at Seoul Women’s University. (We applied Chatham House rules during our conversation, meaning their identities were off-record, to enable them to speak openly.) During a discussion about their generation’s characteristics and perspective on politics and society, one young woman said that even years after taking the suneung, her results still weigh heavily on her mind.

“I sometimes compare myself with my friend, someone who goes to a much higher [ranked] college than I, and sometimes I feel like… I feel like a….”

“Loser,” another student filled in.

“Loser,” the first agreed. “Sometimes.”

The fact that this young woman would call herself a loser in front of a stranger and a room full of peers—and that the majority of the students around the table nodded and hummed their agreement—struck me as unusual and telling.

“There’s a hierarchy between universities,” another student jumped in to explain. “If you go to Seoul University, you are in the top tier, but if you go to our university, some people say you’re a loser because you are in a lower rank. Even if we are all clear of the suneung, we still compare ourselves to each other, constantly.”

The competition does not end after graduating from university or getting an impressive job. Many speak of being afflicted by “relative deprivation,” an insecurity caused by feeling that one is less impressive in comparison to peers—or, perhaps more injuriously, that someone else’s success is responsible for your own “deprivation.”

Relative deprivation has its roots in the evaluation system used by South Korean schools. Teachers are required to meet certain quotas when distributing grades: for example, 20 percent of students must receive As; 30 to 40 percent, Bs; and 30 to 40 percent, Cs. That means students could answer nearly all exam questions correctly and still receive a B or C depending on how their classmates fare. Many say the grading system conditions South Koreans to be highly competitive with one another and derive self-worth from besting their peers.

Last year, President Yoon Suk Yeol enacted reforms aimed not necessarily at lowering the level of competition between students but rather restoring “fairness” by reducing students’ reliance on private education to pass the suneung, according to an October press release from the Education Ministry. It has targeted not only “killer questions” but also what Yoon refers to as the “private education cartel.” The hagwons, private high schools and expensive tutors that make up the private education sector are engaged in corrupt practices, he alleges, such as bribing officials for exam papers and sharing specialized information and resources with one another in a way that takes advantage of students and their families. Two weeks after announcing that it would be investigating the education system, the Education Ministry reported it had received 325 reports of misconduct, including 81 by so-called private education cartels.

By addressing education injustices, Yoon is also hoping to affect South Korea’s worrying population decline. The birth rate—the lowest in the world at 0.78—has led to widespread fears that the shrinking workforce and aging population will lead to economic decline. These days, it’s common to hear talk of Korean “extinction.”

The exorbitant cost of private education factors heavily when Koreans consider whether or not to have children. With nearly 80 percent of students attending hagwons, South Koreans spent a record $20 billion on private education in 2022. Families with students spend as much or more on education per month as they do on food and housing, according to the Korea Times. As a result, the country is the most expensive in the world to raise a child.

When I asked students, teachers and parents about Yoon’s policy changes, they seemed uncertain about the effect they would have. Perhaps it’s too soon to tell. But it was clear that addressing issues like the mental health crisis will require broader, sustained reforms.

“Going in the direction of reducing the burden on students, such as removing killer questions or eliminating the private education cartel, is correct,” a public school vice principal named Jeong-heon Shin told me during an interview at his desk at Ilsan-dong High School in the populous Seoul suburb of Goyang. “However, students felt that the CSAT was very difficult this year, so I am not sure whether the goal of removing the killer questions has been achieved.”

A soft-spoken man, Shin told me he is concerned about his students’ mental health and has made efforts to help, including by arranging counseling for struggling students and organizing school events and clubs where everyone can “find some enjoyment and relieve stress.” But on some level, he told me, he feels there is nothing he can do.

“There are many students who have the desire and goal to go to college, and the current school system is in place for those students. I don’t think Korean schools can deny that reality and just make [the students] feel happy,” Shin said. “So I have no choice but to emphasize things like going to college, which are necessary in the reality that Korean students face.”

Like Shin, students, teachers and parents see themselves as having to adapt to a competitive reality that is far bigger than they are, with pressures they can’t ignore.

“My younger brother is about to go to high school next year and he always asks me, ‘Why should I study? I want to experience more things that I can only do at my age,’” one of Tizzard’s students told me. “I understand his feelings because I’ve been through that myself. But I also tell him, just like any adult, ‘You should study and go to a great university.’ I think this is a sad reality about our society.”

Even if many South Koreans are dissatisfied with what they see as a competitive, zero-sum reality, the majority also believes real reform seems impossible. With every presidential election, power tends to change hands between conservative and liberal parties, and each spends its term undoing the previous administration’s policies and effecting its own.

It’s two steps forward, two steps back, and in the meantime, many feel no choice but to do their best in a punishing, self-perpetuating system.

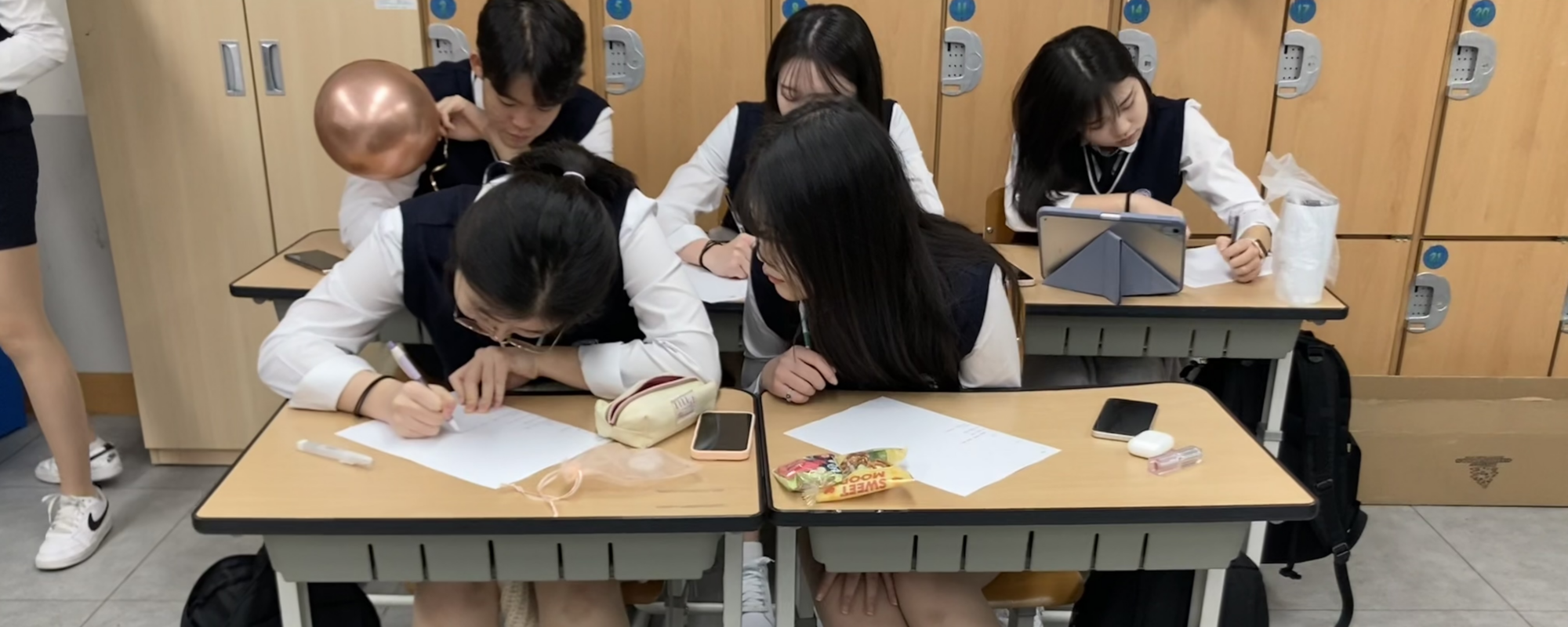

Top photo: Students during an English class at Ilsan-dong High School in Goyang