PARIS — The city is slinking into its summer lull, that sticky molasses of a season where the heat flatlines an otherwise exhausting urban pulse. Bastille Day came and went, the French team won the World Cup and the locals slowly started to trickle out, making way for hordes of fanny-pack-clad tourists who trudge through the humidity, resolute in their mission to eat croissants that turn paper bags translucent with sun-melted butter. They are both glued to their iPhones and seemingly committed to reviving the foldout paper map; add a selfie-stick, and Paris’s undeniably emptier streets are transformed into a new type of obstacle course.

I head to my most recently discovered neighborhood café, La Caravane, to get some writing done outside the confines of my sweltering apartment. The café, on rue de la Fontaine au Roi, in the right bank’s 11th district where I live, is usually peppered with freelancers. But today I’m the only one hunched behind my laptop. I sip the espresso with ice cubes that the barista reluctantly, bewilderedly, prepared for me when I asked for a café glacé—an iced coffee. That, along with air conditioning, isn’t something that has exactly made its way into the French mainstream, although as he withers over his own steaming espresso, I wonder if he might give it a try himself.

Even the routinized controversies over national identity—a fixture of the media and political discourse that have occupied my time for the past ten months—seem muted by the summer’s drawl. It’s been weeks since France became the world soccer champion, but the debate about what the national team players’ origins—the majority are of African descent—reveal about French society is repeating in loops, as if even the polemicists are too checked out to come up with new material. For weeks, my Twitter feed has been clogged with petty debates over whether the team’s players can be described as French-African, or French-Congolese, or French-Algerian, a question that has quickly descended into the tired opposition between the so-called French and American models of diversity—one that prizes integration to create a universal community of citizens, the other that sees itself as a melting pot where difference thrives. That anchored reflex to argue about national identity seems to be running up against the inertia of les grandes vacances—the month of August, when the entire country seems to go on vacation, fleeing Paris for the Mediterranean or the northern coast, anywhere but here.

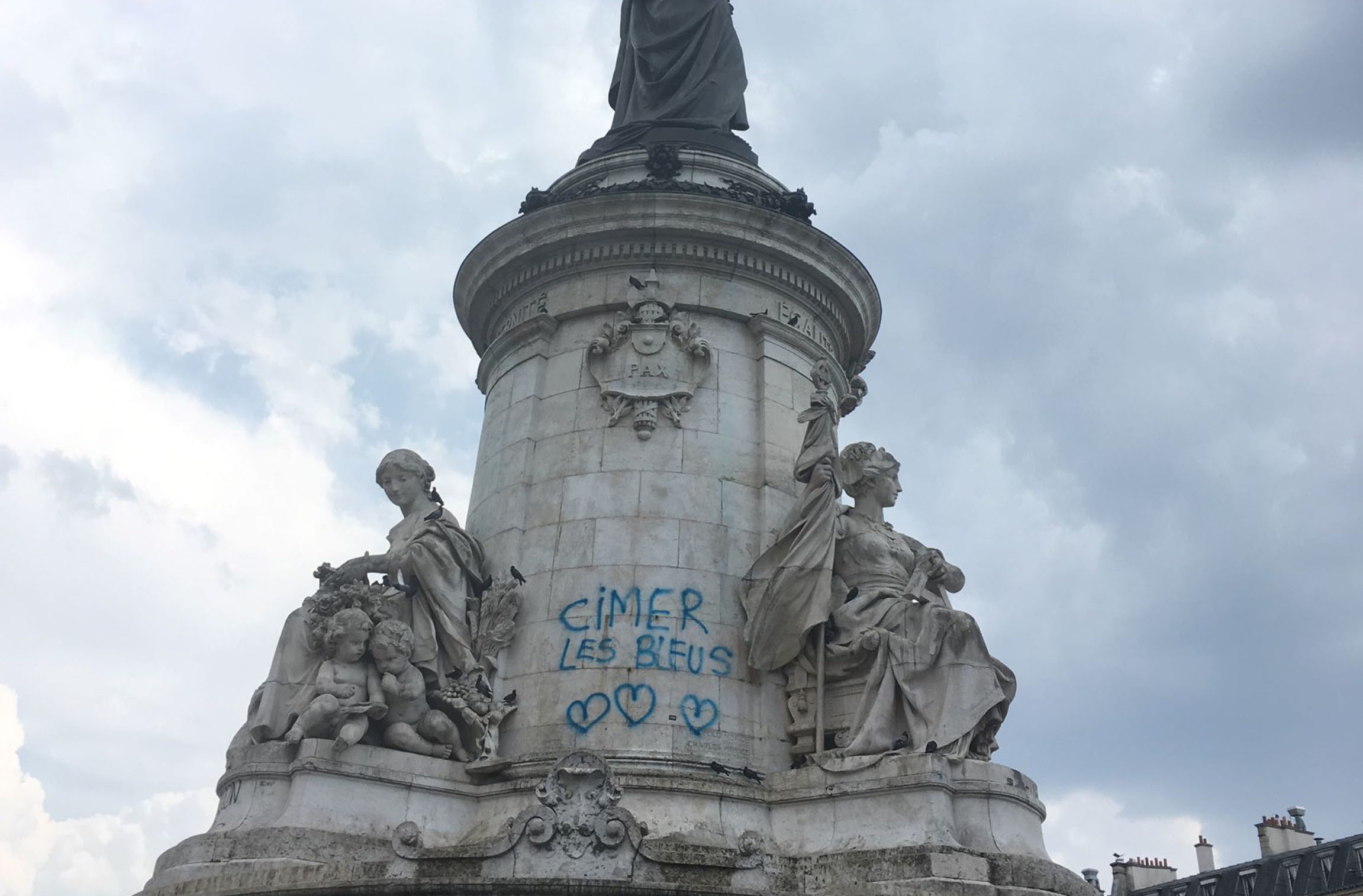

I leave La Caravane and walk up Fontaine au Roi, which runs diagonally through this section of eastern Paris. It starts just above Place de la République—the impressive statue in the center of a sprawling square, still branded with Cimer les Bleus, or Merci les Bleus, in slang, referring to the soccer team, spray-painted on its side—up toward Boulevard de Belleville.

A series of murals catches my eye: startling black and gray depictions of police violence. In one, a helmeted cop pulls a girl by her hair; in another, riot police in full gear hold batons above the national triptych of liberté, égalité, fraternité. Their heft weighs on the words, which are bloodstained and sagging. In another, police fire tear gas at protesters charging toward a sort of palace marked “FMI”—the French acronym for the IMF, an emblem of the neoliberal economics so many here fear President Emmanuel Macron, often labeled “the president of the rich,” dangerously embodies. The images are loud and aggressive, and clash with the street’s stillness—I’m the only one on the block.

The violent images serve as a reminder that even as Paris drifts into its summer sleep, a political scandal is raging: Alexandre Benalla, one of Macron’s security guards, was caught on video violently attacking protesters during a May Day demonstration, wearing civilian clothing but with a riot police helmet. He pulls a woman across the square where demonstrators had gathered. In the next shot, he grabs a man from behind, whom he drags and then hits several times, at one point on the back of the head. The “Benalla affair,” as it has been dubbed, has unleashed a new wave of resentment toward Macron, who the public argues downplayed the incident’s significance and has kept Benalla close—since the incident, numerous photos have revealed the two men side by side. When questioned about his proximity to Benalla, the president has been characteristically cavalier, either refusing to respond to the press or deriding journalists. The affair is consuming media debates and parliament, and has ignited a wave of outrage over both the president’s opacity and police brutality—dark undertones to the summer’s calm.

I turn onto Rue Morand, a short street that takes me to Rue Jean-Pierre Timbaud. It’s midday and the bars and late-night eateries are mostly shuttered, but at night, the street swarms with early-twenty-somethings, who drink overly sweet mojitos and smoke cigarette after cigarette as if the news that they’re bad for you hadn’t quite hit this side of the Atlantic. The bars somewhat abruptly give way to a series of Islamic bookstores—there’s a Salafi mosque around the corner—and Muslim fashion stores, with mannequins covered head-to-toe. Halal butcher shops display cases of rotating rotisserie chickens that glisten; their glass cases fogged with condensation from the heat and grease. Unsurprisingly, the street is a favored reference among those who warn against the “creeping Islamization of France,” with anecdotes about aggressive proselytizing, or men telling women to cover their hair—nothing I’ve ever encountered, but who knows?

There’s a strange disconnect between that closed, unwelcoming depiction peddled by those who fear French Muslims and the total normality of Jean-Pierre Timbaud—it’s a street in my neighborhood, one chapter of Paris’s many cultural pockets, blocks that become their own momentary worlds before ceding ground to something else. I keep walking and pass a string of Tunisian restaurants, air wafting with the savory tang of lablabi—a hefty stew of garlicky garbanzo beans meant to be mopped up with thick chunks of baguette. As if anyone could imagine eating something so soporific in the blazing midday heat.

Deeper into the 11th district

I turn left onto Boulevard de Belleville, that long multilane stretch that starts with North African grocery stores and Halal butcher shops and shifts into a vibrant Asian neighborhood. Bakeries sell baguettes and cornes de gazelles—gazelle horns, a North African crescent-shaped dumpling of a cookie, crisped on the edges and filled with almond paste. The neighborhood is gentrifying, slowly but certainly—I count one, two, three restaurants advertising brunch menus, an irritating import from the United States, because nobody wants to pay that much for an eggs benedict—and chuckle at the Sephora, the cosmetics store, that seemed to emerge out of nowhere in 2015. Last year, the designer brand Chanel drew criticism for its refusal to sell its products “in that neighborhood,” as a spokesperson put it at the time.

I keep walking, and Chinese supermarkets and restaurants punctuate the landscape, with glass storefronts displaying steaming buns and glossy roasted ducks hanging upside down from their legs. Men linger on the median strip.

A quick left takes me to a narrow street lined with multicolored apartment buildings, a refreshing shift from the homogeneity of Parisian architecture that can make the city seem entirely black and white on the cloudiest days. Artists’ studios brush shoulders with new bars that serve beer from Brooklyn and encourage customers to order “share plates” as they sift through the cocktail menu. When the street ends, I pause, turn around and look up, admiring the nuanced color almost reminiscent of the row houses in Washington, DC.

I turn left again, onto rue Saint-Maur, where I pass a series of enticing couscous restaurants before hitting Au Chat Noir, a café I’ve frequented since graduate school, some five years ago. It’s dingy but a fixture of my Paris existence, although it’s true that the bathrooms notoriously lack toilet paper and soap, and I never dare dry my hands on the cloth towel that ominously hangs over the sink. I’m inclined to think it hasn’t been changed since I first discovered this place in 2012, but I focus instead on the cheap coffees—accompanied by a tiny square of dark chocolate—and copious bowls of peanuts and pretzels they serve on repeat with every drink.

The owner, Sari, has become a friend, and he’s one of the reasons I always come back. He’s trim and in his late forties, maybe, and speaks softly in accented French. He’s Kurdish, from Turkey, and hasn’t been back in over two decades—and can’t ever again, he’s told me, although offers only reserved hints as to why; I fill in the blanks, imagining a shadowy activist past. His 19-year-old son, whose lack of Kurdishness he regularly laments, helps out behind the bar and flirts with the clientele. I wonder if his French ex-wife, whom he occasionally references, is the culprit who diluted the culture he had hoped to pass on.

I once thought I was Sari’s favorite customer, but it’s clearly a café full of regulars. I pick a table by the glass windows that are open onto the street today, and survey the hodgepodge of the 11th arrondissement’s quirks that make up the clientele: the old, red-nosed pilier du bar—barfly—who, upon walking in, addresses the room with a confident bonsoir—good evening, even though it’s the middle of the day—and orders an excessively early pastis, an anise-flavored, yellow liquor that becomes cloudy when mixed with water. Three Moroccan men on their lunch break wearing paint-stained work pants squeeze in next to him and order coffees. As the day goes on, a heavy-set black woman nurses a glass of rosé¬ whose contents never seem to diminish. A group of hungry-looking twenty-somethings, two of whom are curiously wearing unseasonal corduroys and plaid shirts, order a round of pints, diving into the bowl of salty, greasy peanuts that is perhaps their dinner.

French demographics

The 11th arrondissement, diverse by any measure, might not be wholly representative of Paris, and even less so of France. It’s also the city’s most heavily populated district, with over 40,000 residents per square kilometer as of 2015, making it the densest neighborhood in Europe. Proximity doesn’t necessarily translate into harmony, and the 11th has in many ways felt the brunt of the tensions that have upended France in recent years: It is home to four of the sites targeted in the November 2015 attacks, where 129 died, and to Sarah Halimi and Mireille Knoll, the two elderly women murdered in anti-Semitic hate crimes in 2017 and 2018.

It’s afternoons like these that make the debates about the so-called French model—which tend to take place in the echo chamber of Paris intellectuals and media personalities—seem so absurd, so brazenly challenged by the city’s day-to-day.

But the arrondissement is also a welcome counterpoint to the narrative of permanent tension and animus that so many journalists—myself included—slip into when describing the social climate here. I was struck by an article in The New York Times about the wild celebrations that followed the World Cup victory: “In France, the crowds surging through the streets on Sunday and Monday mirrored the winning team: multiethnic and multicultural,” it read. “Black, brown and white had no problem coming together, dancing together and waving the country’s flag together—a rare occurrence in France.” From where I’m sitting, those interactions aren’t quite so unusual.

It’s afternoons like these that make the debates about the so-called French model—which tend to take place in the echo chamber of Paris intellectuals and media personalities—seem so absurd, so brazenly challenged by the city’s day-to-day. The alarm bells over the creeping specter of “Anglo-Saxon multiculturalism” end up seeming hyperbolic and purely theoretical. My afternoon walks take me through pockets of distinct communities that bleed that into one another in an undeniably multicultural reality. Much of Paris, then, is a cheeky retort to the navel-gazing radio debates and Twitter fights that get farther and farther away from what’s actually taking place outside.

Since last September, I’ve endeavored to pick away at perceived strains in the French national model, of an imagined story of unity that is supposed to keep the social fabric intact. I’m left thinking about just how ludicrous so many of those debates have become, such a self-reinforcing resignation to caricatured depictions of what France should be. And yet when this corner of Paris clears for the summer, when its packed streets thin out and it becomes shockingly easy to find a table on a café terrace, there is a comfort in the fixture of its ethnic pluralism, etched into its blueprint with such permanence that it can even withstand the grandes vacances.