ISTANBUL — Syrians are no strangers to adversity. One way they have survived more than a decade of war is by relying on one another rather than the state for protection and support.

“Nothing scratches an itch like your own nail,” says Ghazwan Koronful, citing a common Syrian proverb. The director of the Syrian Lawyers Association in Turkey, he now lives in Mersin in the south of the country since having been displaced from his native Aleppo.

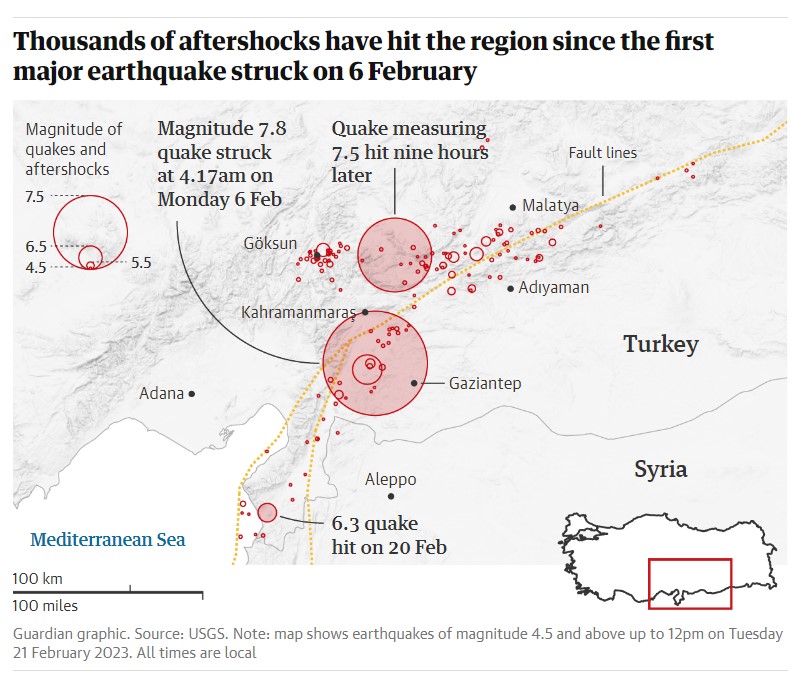

The outbreak of civil war in 2011 led to the world’s largest civilian movement of the 21st century. Now millions of Syrians have been left homeless again by the back-to-back earthquakes that struck southeastern Turkey and adjoining parts of Syria on February 6, the worst natural disaster in the region this century. Two additional powerful earthquakes ripped through Antakya on February 20. The current death toll is nearing 47,000 and increases daily.

Once again, Syrians’ survival will depend on supporting one another, an upshot of life under unresponsive or repressive governments. Simply put, if they want something to be done, they must often do it themselves.

Still, the most recent tragedy has forced the world to stop ignoring Syrians even if provisionally. The United States temporarily eased sanctions on Syria to accelerate aid to the country’s northwest. Berlin has allowed Turkish and Syrian residents to bring relatives in disaster areas to Germany for three months.

Opaque regional geopolitical dynamics have also upended. A plane carrying aid from Saudi Arabia landed in Aleppo, the first such shipment by the kingdom to Syrian government-controlled territory since the conflict began. But international relief efforts inside Syria have been slow compared to aid that has flooded into Turkey. Although different authorities have focused attention on assisting victims in need, Syrians still primarily look to one another for help.

Around 4 million Syrians in Turkey have friends and family affected across the latest earthquake zone. Syrians in government-controlled areas, rebel-held opposition areas, as well as in Turkey, each face different challenges accessing humanitarian assistance. Unsurprisingly perhaps, Syrians in Turkey have focused aid efforts on their brethren in southern Turkey whom they can easily access and who have been the most affected by recent events.

Ali Al Dweik was in Antakya, in southern Turkey, the night the earthquakes hit. A slim Syrian man, he had yet to find an apartment, with landlords wary of renting to single Syrian males. Turkish police had recently detained him in Istanbul and sent him back to Antakya, where he had first been offered temporary protection when he fled Homs a decade ago.

As the ground shook the night the earthquakes hit, he got out of his hotel room before it collapsed. “I was barefoot and it was raining heavily,” he told me. “The land was cracking and buildings were falling all around me.”

After 30 seconds of confusion, everything snapped back into focus. People were crying out to be saved. Ali ran to the rubble, and using his bare hands, shards of metal and whatever else he could find, dug people out. He worked through the night, using his small body to pretzel into tight spaces to locate survivors. By daybreak, he had freed a Syrian mother who had lost her children, and a Turkish husband who had lost his wife.

By the time rescue teams arrived, Ali had already saved nine victims and extracted the bodies of 10. “It was never an option or a choice to decide to help, it was instantaneous,” he said about others calling him a hero.

In Mersin, less than 300 kilometers from the epicenter of the earthquake but still relatively unscathed, Syrians also moved quickly to help. Syrian society is built on trust and networks, which remain intact despite—perhaps because of—a maelstrom of war, impoverishment, and now, natural disaster.

Lawyer Ghazwan Koronful’s youngest son took his father’s words to heart. In the wake of the shock, Mohammed Koronful, a university student in Mersin, and his friends began distributing food, blankets and medicine. “We are using very simple methods, no websites or anything like that,” he said, matching needs and supplies via WhatsApp and word of mouth. Syrian businesses in the city have also retrofitted their offices with dividers and mattresses to provide temporary shelter to affected Syrians.

Across Turkey, many in the Syrian community are doing whatever they can. Restaurateurs in Istanbul have driven supplies to southern Turkey and operate mobile kitchens, offering hot meals to victims. Programmers set up a website to locate those who had initially gone missing. Molham Volunteering Team, a Syrian NGO, organized bus trips to transfer survivors to other cities.

Jin Dawod, a Syrian living in Sanliurfa, fled the city with her family. Even those like Jin, in her early 20s, whose homes remain intact, are too scared to return. The fact of the earthquake is still impossible to process, Jin told me, so she made her online therapy platform, which offers sessions in Arabic, Turkish and Kurdish, free for anyone affected by the earthquake—both Syrians and Turks. “It was long and scary,” she said. “The earthquake has brought new trauma and millions have been hurt. The morning after the quake, we began accepting applications.”

With the Turkish government suspending regulations that typically restrict Syrian refugees from moving freely around Turkey, Syrians across the country were also able to open their homes to family, friends and strangers in need of shelter.

Rana Al Masri, a Syrian journalist living in Istanbul, hosted a friend’s father whose house in southern Turkey had been damaged. “Charity begins at home,” she said.

But crises can also drive communities further apart. Anti-Syrian resentment and hate crimes in Turkey had already been on the rise long before the earthquake hit. But in its aftermath, some Turks have accused Syrians looting amid the chaos, while others said Syrians were taking up scarce resources. One group of Turks circulated a nativist video of themselves chanting about two Turkish cities: “Let’s shoot the Syrians in Hatay, let’s shoot the Afghans in Kahramanmaras!”

It’s well known by now that only a fraction of the aid available to Turkey has made it to Syria. But Syrians in Turkey are also witnessing the government prioritizing its own. Mohammad Koronful and his friends tried to find shelter for displaced Syrians after they were made to leave student housing at Mersin University. “They were told that these facilities were first for Turkish families,” he said. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has promised to hand out 15,000 Turkish lira, roughly $800, to each family made homeless but Syrians do not expect to be included.

Although most acts of kindness between Syrians thus far appear to have been small, their effect is greater than the sum of their parts. “We have to come together and unite in order to get things done,” Al Masri said. Some 5,000 Syrians displaced to Turkey have taken advantage of an offer by the authorities to temporarily return to Syria, many motivated to check in on loved ones.

But Al Masri and others also recognize that given the immense scale of the destruction, their efforts have been only a drop in the bucket. Syrian support networks alone may not prove to be enough this time.

Top photo: Rescue workers search ruins after earthquake hits southeastern Turkey