President Joe Biden is set to host the first-ever Summit for Democracy, part of his promise to reassert democratic values around the world. But with Russia and China panning the very idea of values-based diplomacy, can the event’s more than 110 participants prove them wrong? Norman Eisen and Alina Polyakova are co-authors of a new democracy playbook released December 6, together with The Cable’s co-host Jonathan Katz. They talk to Gregory Feifer about their action plan and what the summit must do to succeed.

Guests

AMBASSADOR NORMAN EISEN (Ret.)

AMBASSADOR NORMAN EISEN (Ret.)

Senior Fellow in Governance Studies at the Brookings Institution

Special Counsel to the House Judiciary Committee from 2019 to 2020, including for the impeachment and trial of former President Donald Trump

President and CEO of the Center for European Policy Analysis

Former Director for Global Democracy and Emerging Technology at the Brookings Institution

Hosts

Executive Director, Institute of Current World Affairs

Journalist, author of Russians: The People Behind the Power

JONATHAN KATZ

JONATHAN KATZ

Senior Fellow and Director of Democracy Initiatives, The German Marshall Fund of the United States

Former Deputy Assistant Administrator, Europe and Eurasia Bureau, US Agency for International Development

The Cable is produced by Glenn Kates. Alexandra Wasielak provided research. Audio mastering by Danil Komar.

Read the transcript:

Gregory Feifer: President Joe Biden has promised to help renew democracy and counter backsliding around the world. As part of the effort, the United States is set to host the first summit for Democracy, together with more than 100 countries and other partners this month. But some of those not on the invitation list have taken notice. The Russian and Chinese ambassadors to the United States have published a joint essay handing the very idea of values based diplomacy as a relic of the Cold War. Can Western democracies prove them wrong and use the summit to reassert democratic values?

I’m Gregory Feifer, and this is the cable, the transatlantic discussion about the front lines of democracy. It’s produced in Washington by the Transatlantic Democracy Working Group and the Institute of Current World Affairs. This is a special edition because my co-host Jonathan Katz happens to be a coauthor of an important new report called The Democracy Playbook. It lays out a 10 point action plan as a guide for the Democracy Summit participants.

We’re joined today by two more of the report’s coauthors. Dr. Alina Polyakova is in Washington. She’s president and CEO of the Center for European Policy Analysis and an expert on transatlantic relations with a focus on European politics, Russian foreign policy and digital technologies. She’s the author of the book The Dark Side of European Integration and major reports on disinformation and democracy in Europe. Also joining from Washington is Ambassador Norman Eisen. He served in the White House as special counsel and special assistant to President Barack Obama for ethics and government reform, and later a special counsel to the House Judiciary Committee during the first Trump impeachment. Norm was also ambassador to the Czech Republic and has been a leading voice in this country for bringing accountability to the previous administration, not least over the Jan. 6 insurrection. And it’s important to note he was also an inspiration for Deputy Kovacs, the crusading lawyer in Wes Anderson’s film The Grand Budapest Hotel. Welcome, Norm.

Norm Eisen: Thank you. Greg, it’s so wonderful to be here with John and Alina, my coauthors and friends.

Gregory Feifer: Congratulations to you both, and Jonathan, on the Democracy Playbook 2.0, which is an update of the first such playbook released in 2019. I want to start with Jonathan and ask you to highlight the report’s biggest takeaways. What are the main messages to the participants of the Democracy Summit?

Jonathan Katz: Greg, thank you. It’s good to be on the other side having questions asked of me, and it’s great to be here with Alina, Norm and friends who care deeply about democracy, democratic renewal. This collaboration, which includes several other authors, is about being part of this effort that the Biden administration has been pushing, which is democratic renewal and the willingness of governments, citizens and other actors to address some of these deep challenges, make some new commitments, renewed commitments, whether we’re talking about challenging autocracies, countering corruption, as you’ve pointed out, and addressing human rights. And over the past decade, we’ve seen tremendous democratic backsliding globally. And so this democracy playbook, which Norm, Alina and others, this is the second iteration of this playbook, is consistently pushing for potential commitments of Summit for Democracy participants, not only at the upcoming summit—countries and governments can do, or actors like civil society organizations or private sector or labor, but about a year of action that the Biden administration has called for and then a second summit in 2022 and beyond. So we really hope that this democracy playbook will be important for those seeking to build out their commitments right now, those governments, the 110 participants that you mentioned. And within this executive, if you look in the executive summary, these 10 commitments laid out for actors from rule of law, to addressing independent media in investigative journalism, to countering corruption and to also building the type of alliances globally that the Biden administration and other pro-democracy forces want to advance. So this is going to contribute greatly to those that are preparing for this upcoming summit, but also will build out roadmaps.

Gregory Feifer: Alina, I’d like to ask you, the democracy playbook calls the Summit for Democracy historic. How important is it? And do you really think the 10 proposed commitments in your report will influence the proceedings?

Alina Polyakova: Thank you so much for that question, Greg, and it’s so wonderful to be here talking to my friends and colleagues and coauthors about this important report that we’ve put together. And I do think it’s important to highlight that this democracy playbook is a update and a follow on to a report that some of us had published about two years ago that was based on a huge amount of research of the academic literature about what works and what doesn’t. When it comes to pushing forward on democratic governance, democratic transitions and pushing back against anti-democratic movements and so-called illiberal democracies that we’ve seen emerge in some countries in Europe, but now increasingly across the world. So that is all to say, we’re talking about the top line takeaways. But this is all rooted in a lot of academic research literature that we really tried to put together to come up with actionable concrete policy options. There’s a lot to dig into. So to your question about whether this is a historic moment, I think it is one. We have not seen this kind of prioritization of democracy, democratic governance in institutions and most of all democratic values and principles from a US administration for quite some time. Needless to say, for those of us, for those of you listening that this wasn’t a top priority for the last administration. I think prior to that, we didn’t think that we needed to invest in such a high level and with so much intensity into coalescing around our values and principles. So I think right now we have a window of opportunity to align, to recommit to democratic values and principles around integrity, around transparency, around accountability, in an effort to push back against what has been a rising tide of autocracy across the world. And I think this is where the Democracy Summit is so critical to bringing the community of democracies together to recommitting to our values and as we suggest in the report, to getting some real commitments in place. So it’s not just a meeting for the sake of a meeting that we actually have some real commitments that this community can sign up for and then that we can follow up on over the next year of action, but even beyond that.

Gregory Feifer: Norm, the Summit for Democracy is taking place exactly a month before the first anniversary of the Jan. 6 insurrection. Too many Republicans close to former President Trump have been busy whitewashing the events of that day, and the Biden administration’s Justice Department has yet to hold to account the elected officials who encouraged the insurrection. Some of us are growing very concerned about the possibility of any real accountability. So does the US have the standing it needs? And does Joe Biden have the will or political capital to actually lead a renewal of democracy globally with so much uncertainty going on at home?

Norm Eisen: Greg, when I had the privilege of representing our nation abroad as ambassador in the Czech Republic, I always made the point that the United States led as partners, that we were colleagues, that we were walking side by side on that steep up and down the road of democracy, that we were far from perfect. And I think that while I would prefer that the US was not having its current struggles, let me say, by the way, that I view the American electorate’s thoroughgoing rejection of ex-President Trump in 2020, however much he may deny it as a rejection of the illiberal turn that he represented. So there is, for the moment, happy inflection point, although the struggles continue. All of that does have a curious advantage in approaching the issues that are going to be tackled at the Democracy Summit. The issues that we lay out in our 2021 Democracy Summit edition. It gives us a more humble perch, but a more honest one to talk, frankly, about the challenges of preserving democracy, of reversing democratic backsliding, of dealing with the related issues like anti-corruption, promoting human rights that that are intimately intertwined with saving democracy. So I wish we didn’t have this credibility, but I do think that we can approach our fellow democracies from a more humble perspective, with some lessons learned from the prior administration. Ongoing lessons and maybe in the long run that will actually enable democracy to thrive even better.

Jonathan Katz: Norm, you lay out this case for obviously what took place over the last year. And I wanted to ask you as you’ve been so involved and focused on U.S. domestic democracy issues, are we worse off today than we were on January 6.

Norm Eisen: Jonathan, I think the jury is still out. I’m reminded of the famous and perhaps apocryphal conversation between Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai in which Kissinger is said to have asked, “What do you think of the French Revolution?” And Zhou Enlai supposedly replied, “It’s too soon to tell.” And I think it’s really too soon to tell. It’s important to avoid overly hasty analysis, but I think certainly there’s worrying developments, but let’s see how things develop. There’s federal legislation, there’s challenges to it that would deal with voter suppression, with state legislatures attempting to hijack outcomes with this terrible gerrymandering that we see all over the country that federal legislation passes in the coming months, then things will look very different. So I’m not yet prepared to say we’re worse off and still basking in the afterglow of what I view not as a partisan election only, but really as a referendum on democracy in the United States in 2020, and democracy won.

Jonathan Katz: Alina, you’re an expert on disinformation, not least from social media trolls and other Russian influence on our elections. If we can’t counter or struggle to counter that kind of meddling at home, what hope do we have of helping counter it elsewhere?

Alina Polyakova: Well, thanks Jonathan, and just to pick up on the conversation you were just having with Norm about the US domestic environment. You know, one of the things that we’re trying to do with our report and with this part, the broader conversation around democracy is also to highlight that not only are we having our own domestic issues with democracy and democratic governance and trust in institutions in the US, but clearly some of the first movers on counter democratic actions and efforts have emerged in central Eastern Europe. And I think this is really important to remember because I think often we think that whatever happens over there doesn’t really touch us here in the United States. But I think what has become very clear is that this is a global problem and in many ways, autocratic leaders learn from each other. And in many ways, we’re seeing very similar patterns emerge across several central Eastern European countries, but also on other countries around the world. And I think if we want to understand what is the toolkit, there will need to be keeping an eye on and being very vigilant about, especially those of us in the civil society space. We should be looking at countries where we’ve had some very troubling rollbacks in democracy and how authoritarian oriented leaders are reshaping their societies after coming to power through democratic elections. So it’s not really a coup model that I think a lot of people often think about. It’s really a slow creep of rollbacks that happen at an institutional level. And then before you know it, you no longer living a democratic society and then to go to your question of disinformation. Of course, disinformation and propaganda more broadly is a tool of authoritarian states that authoritarian government launch against their own populations. And, of course, launch against those who they see as competitors are similar threats. Most of us in the United States only became aware of Russian disinformation efforts as a result of Russian attacks and interference in 2016 elections. But certainly countries like Ukraine and Georgia, Moldova and every single Baltic state have lived with disinformation attacks from Russia for a very long time. And I think if we were looking as to what was happening in these countries in advance, we would have been better prepared and less taken by surprise in 2016. And I think you’re right. Unfortunately, despite the now huge attention to this issue since the 2016 US election, we haven’t made a lot of progress on deterring disinformation campaigns, not just from foreign actors like Russia, China, Iran, North Korea and other authoritarian states that we often put in one basket, but also domestic disinformation. How specific groups try to misinform and mislead our populations about basic facts, that undermines in the long-term trust in our public institutions. And, of course, look no further than the current pandemic we’re still in and how much disinformation we’ve seen from so many sources, both domestic and foreign, when it comes to anti-vaccine disinformation campaigns, which of course, is just a slow drip on a growing distrust in the kind of messages we’re hearing from our own governments. And I think it is a bit of a depressing picture, and there’s a couple of reasons for that. If I can just point those out very quickly. From the very beginning, we started to focus so much on understanding how content spreads online, and there’s a huge amount of research now looking at how does this meme travel, you know, across Twitter, jump to Facebook and then end up elsewhere in the social media domain. There’s also a lot of research just showing how some Russian intelligence agencies, for example, carry out various kinds of disinformation operations. Fact checking has been a huge industry, but I think we’re getting lost and we’re missing the forest for the trees here. By focusing on these disparate disinformation campaigns, we’re not seeing the bigger picture. And the bigger picture, of course, is that what these disinformation campaigns, whether they’re domestic or foreign, really target is that soft underbelly of democracy, and that is the trust between individual citizens and democratic institutions. And this is where I think the greatest vulnerability really is.

Gregory Feifer: A question for all three of you, or any of you. And to continue this idea of the soft underbelly back here at home, Anne Applebaum has just published a piece in the Atlantic titled “The Bad Guys Are Winning,” partly because they share common interests. As Alina, you just mentioned, and they can exploit new tools like social media that hugely amplify their propaganda. Some of the writing in the piece by the Chinese and Russian ambassadors may read like parody, but they also use popular tropes, equating democracy building with popular Western military intervention. So how do democratic governments convince their own people that democracy around the world is worth spending limited resources on?

Alina Polyakova: I can start us off there. I think to my mind, the big picture here is to ask people, would you rather live in a free and open society? Or would you rather live in a closed society where you’re closely monitored and surveilled? And then your personal data is used against you to potentially imprison you or detain you for posting something on your social media account? I think if we really describe to people what a democratic society is and what authoritarian society is, I don’t think you’re going to get too many people saying, well, I’d really like to live in an authoritarian country. But unfortunately, we’re not doing enough to really sell what are the benefits of living in a democracy. There are huge benefits. I hope that goes without saying to live in democratic societies, the freedom of expression, the freedom of choice, even the freedom that we have and a lot of our countries to make decisions that may not be for the public good at the end of the day, but they’re based on your individual rights. And I think this is where we have failed on the message side because we have focused so much in navel gazing as to what’s wrong with our society. Authoritarians are winning because every time there’s a protest or demonstration in a democratic country or, for example, when the U.S. withdrew from Afghanistan and there were some really troubling pictures that emerged from that. This is what you see on Russian state media. This is what you see on Chinese state media. And the picture that’s being sold is democracies aren’t stable. Democracies cannot manage themselves. And do you really want to live in that kind of society? And when we constantly harp on our deficiencies as well, we just amplify and lend greater credibility to that narrative.

Norm Eisen: I’ll jump in to say, I often wonder if the need isn’t really for an ethical, democratic populism that understands not so much the tell the negative story of how terrible our lives would be under authoritarianism, but that seizes some of the messaging and the skills of populism. But instead of hate, it does it with love, instead of lies with truth. But there does have a sense the populists are so good at finding galvanizing issues, and it may be that the affirmative vision of democracy just doesn’t lend itself to this kind of an approach. But I do think that there are examples I could make for this love case. The revulsion of the corruption scandals, the response president of Slovakia running on a strong anti-corruption platform, but with a positive vision of where she wanted to take the country. One of the things that characterizes the illiberals, the demagogues, is that they pick a fight with a cartoon like villain, and then they have a series of fights with a series of villains. You know, we need to have that galvanizing quality of what we’re fighting for, but fighting something positive.

Jonathan Katz: What I just want to add on the democracy issue that you raised with Greg about what can be successful or why we need to address this challenge of Russian and Chinese messaging on this issue. And that’s just simply about democracies delivering for their citizens. And Norm highlighted Slovakia as a country as an example. I can point to Moldova, where you’ve had successive governments over the last three decades that are either been corrupt oligarchs or corrupt leaders beholden to Russia. And you finally have a leader in Moldova, Maia Sandu, I think really shines as the example of the type of ethical leader that Norm spoke about, Maia Sandu, who maybe some people gave very little shot at becoming president and then having a party win in parliament that the citizens, when given choices to have ethical leaders, I think, like we saw in the last US presidential election, can and do pick the right set of leaders who then need the support and help, like Moldova does need today to continue to address the challenges that have set that country back for the last three decades since independence.

Gregory Feifer: Norm, I want to ask you about making the case for democracy abroad, authoritarians who have been attempting to advance the argument that their top-down governance systems are better equipped to deal with serious challenges facing societies today from Covid to climate change? What’s your response?

Norm Eisen: Well, I do not accept the premise, of course, that autocratic regimes are more effective in meeting challenges. I think the experience of the United States has illustrated that we were more effective in meeting the challenge of Covid when we took a step back from autocracy. I think if you look at the ways that China attempts to compete globally, you have governments, whether it’s across Africa, in Europe, the Czechs are having a painful experience with this now that are burned, they draw their hands back as if from a hot stove when they attempt to deal with those autocratic regimes. If you look at the economic struggles of Putin’s Russia, you see another example of this. So that being said, I will concede that I think one of the great challenges of the 21st century is going to be dealing with the Chinese approach of hybridizing, a form of state-controlled capitalism with an illiberal regime. So I don’t doubt that the challenge is there. But I just I push back on the argument whenever I hear it.

Gregory Feifer: Alina, I’d like to ask you to look at a specific real world crisis and a potential first test for democratic assertiveness following the Democracy Summit. How should the Biden administration and other democracies be responding to Russia’s massive buildup of troops on the border with Ukraine? And how should they respond if Russia actually invades Ukraine again?

Alina Polyakova: I think clearly, one thing the Kremlin has learned is when U.S. attention seems to be elsewhere and primarily, we’ve been very clear and signaling that our attention from a national security perspective is going to be focused on the Indo-Pacific. Kremlin officials have taken that to mean that this is an opportunity for them to get some serious concessions from the broader NATO alliance and certainly from the United States. And I think this is what this buildup is truly about. But certainly, I don’t want to underestimate the potential for a new military confrontation where we see an aggressive Russian force move into Ukraine again and actually work to get more territory under its control. But I think if you look across Europe, what’s happening in Ukraine is just one piece of the puzzle we see very nefarious, kinetic and non-kinetic Russian activities in the Balkans. Of course, the crisis with refugees and migration on EU’s border between Poland and Belarus. Yes, the Belarussian dictator Lukashenko is the primary actor there, but he has his supporter and his lifeline that goes directly to Moscow. So I think if we look at the bigger picture and pan out a little bit, certainly Ukraine stands out as the highest area of concern. But we’re seeing really a pattern of military aggression that Russia has been waging across Europe. And I think what we’re seeing now is a response. We just had some statements of warning issued by NATO leaders. We had the NATO ministerial meeting just recently with some strong statements issued warning Russia not to move against Ukraine. We’ve seen the administration be very active on the diplomatic front and trying to bring together the transatlantic community to send signals to the Kremlin that there will be consequences for any increased aggression. But I think at the end of the day, what many have learned, including Moscow, is that often there’s not much meat behind words of concern coming from Western democracies. And we have spent too much time, I think, worrying about how will Russia react to, you know, our desire to work more closely with Kiev to make sure Ukraine accomplishes what the Ukrainian people want, which is greater democratic governance, a greater democratic freedom and integration into your Atlantic institutions. And instead of doing that in a much more assertive way, we’re constantly worried about whether whatever we do is going to provoke Russia toward some great war. And at the end of the day, I don’t think that’s in the Kremlin’s interests because they will lose a lot in terms of blood and treasure in such a conflict.

Jonathan Katz: I want to turn to the participants. Alina and Norm, there have been 110 countries and partners have been invited to participate in the Democracy Summit. It’s no surprise countries such as China and Russia and Belarus and North Korea haven’t been asked. But there’s also been glaring emissions in the transatlantic space, including NATO allies Turkey and Hungary. Why were those countries not invited? And was that a good idea to exclude them?

Norm Eisen: Well, Jonathan, it’s always the question of the carrot and the stick. But Turkey and Hungary are two of the poster nations for democratic backsliding for illiberalism. Alina and I and other Brookings colleagues wrote about that in the first report in the series that included the first edition of the democracy playbook. And so I think under the circumstances, it makes a mockery of this summit to include them because they’ve been such leaders in developing the illiberal model. So like China and Russia, I think it’s appropriate to omit them. It’s not an easy choice to make. It’s an agonizing one, and I certainly could see going the other way. But I support the decision to, in effect, call them out for their offenses against liberal democracy.

Alina Polyakova: You know, I’m of two minds on this, primarily because the way that the administration structured the summit is at the governmental level. I think not inviting a country like Hungary. Well, on the one hand, it makes sense because by many measures, including Freedom House Democracy Indices, Hungary doesn’t look like a democracy anymore. But I think we can’t let Hungary go. And I think the way you influence is through engagement. And I hope that even though there was this lack of public invitation, there are private conversations, diplomatic conversations that are happening between the US administration and the European Union, and, of course, Hungarian leaders about what’s what’s really wrong here and how to get the country back on its path. Because I think at the end of the day, what we’ve seen over the last several administrations is that isolating these countries doesn’t really work. It doesn’t get them on the right path. If anything, it solidifies the position of these self-styled illiberal leaders. Nor does embrace work, which is what we saw under the last administration. And I think we have to find a middle ground here, at the end of the day because we really can’t afford to let any ally slip completely out of our reach.

Gregory Feifer: Norm and Alina, I’d like to wrap it up on this. A Washington Post column by Morton Abramowitz and David Kramer, the current president and former president of Freedom House, earlier this month warned that the worst possible outcome for the Democracy Summit would be devolving into a kind of form for empty speeches and no action. The organizers have promised the next year to be a year of action, as you’ve mentioned with follow up meetings to gauge progress. But how will we know if real progress is or isn’t being made?

Norm Eisen: Well, we won’t know right away if this summit has been a success or not. We’ll have an indication because we’ll be able to assess the concrete commitments that participants have made. But then we’re going to have to use this year of action to grade whether people are actually following through. But even then, these are the seeds of democracy, these commitments that are being planted. We’ll want to see how those grow and flourish. And we hope they will.

Alina Polyakova: Yeah, I think that’s a great question. I mean, to be honest, I think we have to set our expectations for success relatively low. This is a virtual summit, which does matter. You can’t engage in some ways as effectively online as you can in person. And, it’s not 100 percent clear if we’re going to get real announcements and real commitments as a result of this summit. So to my mind, what I would consider a success is if at the very baseline all of the participants can recommit to democratic values and principles and then commit to collaborating on a concrete agenda for the year ahead with follow up sessions, as well as potential working groups on some of the core issues. But I think the fact that we even have the opportunity to come together as a community of democracies is very significant. And I think the entire world has been watching this very, very closely, and I hope that we will get some commitments on the table.

Gregory Feifer: Alina, Norm and Jonathan, thank you all very, very much.

Alina Polyakova: Thank you for having us.

Norm Eisen: Wonderful conversation. Thank you.

Jonathan Katz: Thank you.

Gregory Feifer: That was Ambassador Norman Eisen and Dr. Alina Polyakova. Their democracy playbook will be published Monday, December 6th at www.Brookings.edu and the websites of the German Marshall Fund, the Center for European Policy Analysis and the Transatlantic Democracy Working Group. And this is The Cable, hosted by Jonathan Katz and me, Gregory Feifer. Glenn Kates is the producer. Alexandra Wasielak provided research and Danil Komar conducted audio mastering. If you like what you heard today, please share this podcast with your colleagues and friends. Subscribe wherever you listen to your podcasts, and if you listen on Apple, please take a second to rate us.

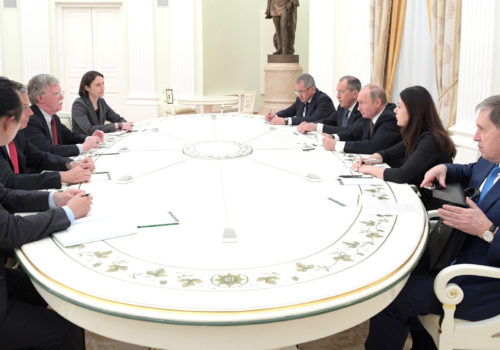

Photo credit: Office of the President of the United States