7 March 2016

One Sunday in January, Islam Gawish was running late. The 26-year-old cartoonist, famous for sardonic stick figures published on his viral Facebook page “El-Warka” or “The Paper,” was due at the Cairo International Book Fair for a friend’s book launch. But at midday, a group of police investigators burst into the Egypt News Network, an outlet headquartered in Nasr City where Gawish keeps an office. The police began rummaging through ENN’s equipment and, soon enough, Gawish’s work space.

“Does the El-Warka project have a license?” the commanding officer asked Gawish.

“A license for what, sir?”

“You manage a website without a license.”

Behind big black glasses, his hair strewn about, Gawish tried to explain to the officer that this had to be a mistake. El-Warka is just a Facebook page. It may boast 1.5 million followers, but it is not a standalone website and has no official relationship to ENN. After examining the cartoonist’s electronics and poking through comics on his computer, the officer accused him of “drawing the overthrow of politics.” The officers marched Gawish and ENN’s financial manager out of the building. By 1pm, they arrived at the Nasr City Police Station.

After waiting outside the interrogation rooms, the officers returned the financial manager’s ID and told him to leave. Gawish was summoned into a room for questioning. He knew from his friends that this police station’s mandate includes monitoring creative production and social media.

Two officers were waiting inside. One handed him a piece of paper with a written statement, asserting that Gawish manages a website without a permit, possesses unlicensed software, and draws cartoons that seek “to topple the symbols of the state.” The officers gently persuaded Gawish to sign it. “Sir, I don’t understand the law, and I will only proceed in the presence of a lawyer,” he said. The officers departed to draw up another statement. They left the cartoonist sitting there, telling him that the prosecutor would meet with him later that evening. He never arrived. The cartoonist spent the night in custody.

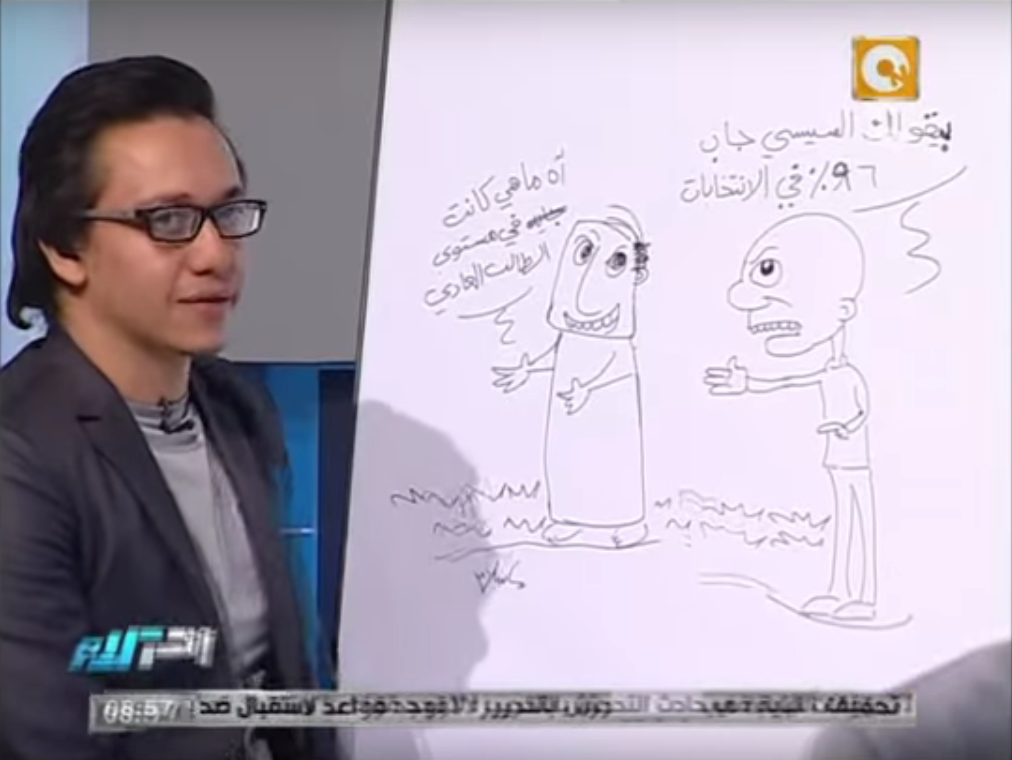

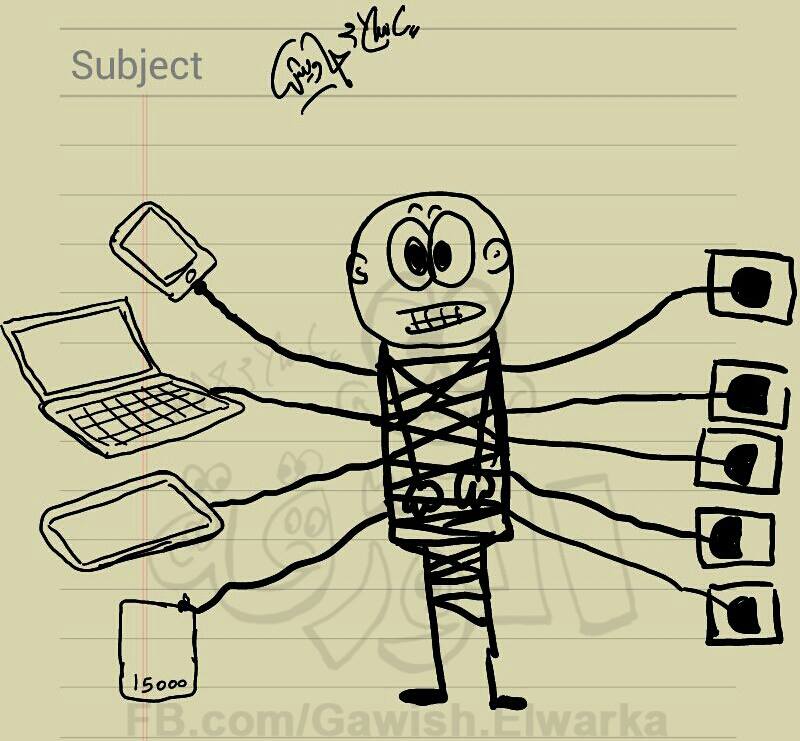

On spiral-bound notebook sheets, Gawish illustrates comics of social and political issues, though most of his cartoons laugh at innocuous things like pop songs, relationships, or the weather. His jokes are anti-establishment but not exceptional. Independent newspapers regularly publish numerous cartoons about police corruption, crony capitalism, and censorship. Caricatures of President Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi, scarce during his rise to power in 2013, now appear often in the local press. Yet perusing a year or more of Gawish’s daily drawings I saw no such assaults on the presidency. Gawish’s stock-in-trade: punch lines about dating and technology. Above all, Gawish has innovated the web comic, mixing methods of caricature and online memes. The Internet has given the young illustrator the opportunity to reach vast audiences without being inhibited by pesky editors.

Overnight, 100,000 new followers “liked” Gawish’s El-Warka Facebook page. A variety of local news outlets as well as the New York Times reported on his detention. Journalists speculated which cartoon was the impetus; they scratched their heads about licensing Facebook pages, something no one had ever heard of. An outpouring of online support followed. “If Islam had embezzled 37 million, they would already be reconciling with him and sending him back home. Enough is enough,” tweeted the superstar comedian Bassem Youssef. Dozens of cartoonists in Egypt put pen to paper in solidarity with their caged colleague. Many illustrations depicted the floppy-haired Gawish facing off with a black-uniformed officer. Others rendered the arrest in stick figures, on lined paper. Andeel drew a bashful President Sisi covering his face, saying, “I don’t like to be drawn.” (The Penal Code prohibits insults to the president, a rule that Andeel and many of his fellow cartoonists flaunt daily.)

The next morning, the prosecutor arrived at the police station. He sent Islam Gawish home without charge.

“I don’t know why I was arrested. It seemed that they wanted to arrest someone else, and I was taken by mistake,” Gawish told ONTV, a local broadcaster, days later. “My treatment was good. No one in the prosecution or the police station treated me poorly.”

In this worsening climate, I opted not to interview Gawish and rather piece together the story from his public statements in Arabic. With so much happening in the country, Gawish’s story quickly fell out of the headlines, but I have continued to closely follow his cartoons and hope to interview him in the next period.

Despite a broad crackdown on independent media, researchers and artists, and an even more comprehensive suppression of opposition organizations, it is rare for a cartoonist to be incarcerated in Egypt. Yet Gawish’s arrest, the jailing of a young novelist, and a range of other events in the past month suggest that Egypt is entering a new phase of absurdity. Many have been caught up in an ever-widening dragnet.

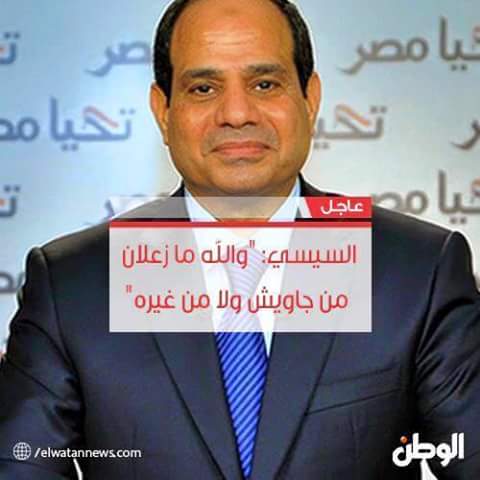

On February 1, President Sisi phoned into the talk show Cairo Today and droned on about the ills facing the country and the need for youth to step up. “My God, I am not upset with Gawish or anyone else,” he said. “No one can speak on my behalf and say that I get upset from criticism.” The president’s remarks seemed to be a direct response to Andeel’s cartoon, as if the former general needed to swagger in the wake of increased dissidence. Sisi went on to downplay Gawish’s arrest. “Every day, the ninety million people in Egypt find many things which make them uncomfortable, like the case of Gawish,” he said. “Such things happen, and this is natural in a country which was in a revolutionary state for four years.”

Upon his release, Gawish finally made it to the Cairo International Book Fair, the annual two-week event hosted by the Ministry of Culture on an expansive campus across from military social clubs and state monuments. In the fair’s main hall, teenagers snapped selfies with officers at the Ministry of Interior and Ministry of Defense’s slickly outfitted booths. Across the lawn and down the road at a publisher’s stall, Gawish launched the second volume of El-Warka, consisting of over 250 pages of stick figures originally posted on his Facebook page. (The first volume of El-Warka, published in January 2015, is already in its twelfth edition, an exceptional feat only achieved in Egypt by literary celebrities such as Naguib Mahfouz.) Teenagers took photos next to life-size caricatures, and Gawish grinned as he signed copy after copy. As I wandered through the literary carnival, his book was on offer at scores of booksellers. “I’m looking for that new book of comics by Islam Gawish,” I heard a 40-something-year-old man say to his friend, as I exited the fairgrounds.

It was easy enough to laugh off the arrest of Gawish, a mishap that bolstered the young cartoonist’s celebrity and showed that, in case of an emergency, a wide support network would defend an arrested dissident. This network was put into action on February 20, when an appeals court sentenced novelist Ahmed Naji to two years in prison. The court convicted him of “violating public modesty” for publishing a sex- and drug-laden excerpt of his novel in the state-owned literary review Akhbar El-Adb. (See A Season in Hell for details).

Ahmed Naji’s imprisonment hit hard. We were becoming fast friends. He is but a year older than me and has been charged for writing fiction, a difficult concept to wrap my head around. Now he is in the notorious Tora Prison, and only family has visitation rights. I wanted to attend press conferences and strategy sessions around this case, but I decided it was a good time to keep my head down. Instead, I watched the proceedings on YouTube and read dozens of articles about Naji in the Arabic press.

This is the first time that a writer has landed in prison in recent memory, perhaps since the time of President Gamal Abdul Nasser. High-profile columnists and novelists pointed to the ridiculousness of the incarceration. (For example, Fifty Shades of Gray is on sale at many Cairo booksellers.) Prominent intellectuals and publishers held public forums to draft a strategy; more than 400 artists signed a public statement against his imprisonment. Akhbar Al-Adb printed a special issue, “Freedom for Ahmed Naji,” with the young novelist on the cover; inside were over 20 articles about him, his caricature appearing on each page. The cultural weekly Cairo left its cover blank in solidary. Dozens of cartoonists expressed their anger at the sentencing in print and online, and they continue to do so. Not surprisingly, Naji’s book extract has been republished online, and two million readers have viewed his purple purpose.

When Minister of Culture Helmy Al-Namnam joined a recent press conference at the Journalists Syndicate calling for Naji’s release, he took to the lectern and employed a technocrat’s logic. “There are articles in the Penal Code that contradict the Constitution and punish publication crimes, despite the need to overturn these laws with the ratification of the Constitution,” said Al-Namnam, referring to article 67 of the 2013 Constitution, which enshrines the artist’s right to free speech. “The imprisonment of art and culture should not be in our society in this age,” he said.

An audience member stood up and said, “This is a dictatorship.” The minister shouted back at the heckler, “Excuse me. Excuse me. Excuse me. Excuse me… What you are doing is a form of dictatorship.”

Naji’s imprisonment and Gawish’s arrest are among a string of troubling incidents over the recent period. Last month, Italian graduate student Giulio Regeni, having gone missing for ten days was found murdered by the side of Cairo-Alexandria Desert Road. Authorities have denied any role in the twenty-eight-year-old’s brutal death, yet his body displayed signs of torture known to be trademarks of the security state’s ruthless interrogation methods. An Italian trade delegation had been in Cairo on January 25, the day Regeni went missing.

When Regeni’s body was discovered, it sent a shock throughout the academic community at the American University in Cairo, where Regeni held an affiliation. My colleagues were disappointed with the University’s feeble response to the tragic incident (on Twitter and in an internal email, the @AUC callously referred to Regeni’s “passing away,” almost in passing). Some community members partook in a demonstration on campus, others signed a public statement condemning the university administration’s reticence. At the faculty’s urging, a memorial was held for Regini several weeks later. Equally troubling is that an unknown number of Egyptians, thought to be in the thousands, have similarly been “forcibly disappeared.”

Meanwhile, the Ministry of Health has declared illegal the Nadeem Center for Rehabilitation of Victims of Violence, which aids the recovery of torture victims. Twenty-year-old Mahmoud Mohamed, who has been sitting in prison for two years on pretrial detention for wearing an anti-torture T-shirt, endures mistreatment and is losing weight. Tens of thousands of others are said to be behind bars without charges. Twelve youngsters were sentenced to five years in prison for blasphemy. A court (mistakenly) sentenced a toddler to life for killing three. Blogger Taymour Al-Sobky is facing charges for “distributing false news” for posting on Facebook that women from Egypt’s south are unfaithful. Tabloid talk show host Riham Saad was sentenced to a half-year in prison for broadcasting pictures of a victim of sexual harassment. Journalist Hossam Bahgat and human rights activist Gamal Eid have been barred from international travel.

The news has been increasingly absurd. The Brother of Al-Qaeda mastermind Ayman Al-Zawahiri was let out of prison. After months of denial, President Sisi finally admitted, albeit in passing, that terrorists had in fact downed the Russian airliner in October. A several-miles-long red carpet was unfurled for President Sisi as his convoy drove to a public housing project’s launch. The first activists to defy a strict anti-protest law in recent months have been members of the Doctors Syndicate, who demonstrated against the police. The Health Minister responded by suing the syndicate. Several weeks later a policeman shot dead a taxi driver in Darb Al-Ahmar neighborhood after a quibble over a $4 fare. In response, hundreds protested the Cairo security directorate, the Interior Ministry’s police headquarters for the capital. Live from Cairo, Saturday Night Live in Arabic premiered. Cognizant of the experience of comedian Bassem Youssef, whose show was curtailed in 2013, Arabic SNL is unlikely to tackle any continuous issues, whether they are politics, religion or sex.

Nevertheless, cracks in the regime’s power are beginning to show. In a meandering speech on live television, President Sisi wagged his finger at the nation. “Please, don’t listen to anyone but me,” he said. “I’m serious. I’m serious.” As for the country’s economic malaise, and in the face of plummeting currency reserves, he remarked, “If it were possible for me to be sold, I would sell myself.” An Egyptian-American responded by posting a “slightly used” Sisi on e-Bay, and the bidding for the mock-item reached over $100,000 before being removed by the site. (Earlier this month, when Sisi predicted that democracy would take hold in a half-century, Facebook users created an event invitation for January 21, 2063; the RSVP list has reached 37,000.)

Yes, between the lines, with humor and in certain sanctioned spaces, dissent endures. For weeks I had been trying to interview Alaa Al-Aswany, the best-selling novelist. He had supported the 2011 uprising, then the 2013 coup and its attendant lethal suppression of dissent, and now has turned his keyboard against the state. Aswany invited me to his weekly cultural seminar. On a recent Thursday, I headed to a mansion called “Revolution House,” a 25-minute walk from Tahrir Square, where I expected an intimate affair. The theme was, “Why We Oppose the Dictator,” audacious in this environment to say the least.

I wandered around for an hour trying to find the address, asking a dozen shopkeepers and doormen without letting on where I was headed. Each sent me in a different direction. Finally a half-block from my destination, I was surprised to hear the word “dictator” intoned over the loudspeaker. Entering the courtyard, I saw Aswany sitting on stage alongside two other writers, entertaining an audience of a hundred or more. He smoked cigarettes and spoke in paragraphs, describing the five characteristics of a dictator (paranoia, insulation, sadism, narcissism, and controlling the masses). Aswany often referred to the president as “Sisi,” in stark contrast to local newscasters and talking heads who always call the leader by his full name and title.

In a strange way, Aswany’s salon was just as dictatorial as the president’s longwinded remarks. The opposition author opened up the floor for questions at the end, but the forum hardly felt like a conversation; it was more of an opportunity for Aswany to pontificate. In contrast, Islam Gawish regularly takes submissions from readers, turning them into drawings, and he always acknowledges their creator. The final pages of the cartoonist’s new book invite the reader to participate: “Draw yourself or someone close to you and write a caption,” which Gawish would then happily post online.

Gawish remains defiant, adamant not only on his right to free expression but also insistent that he poses no threat to the regime. “I will continue drawing my ideas. I will not stop drawing,” he posted on his Facebook page upon his release. “I am neither cheering for anyone, nor am I insulting anyone. I am not biased toward anyone. I have my own opinions, whether intellectual or political, and I am not extreme in my ideas. I do not claim to be a hero or a role model.” In January 2014 his Facebook page had but 50,000 fans; now his audience has swelled to 1.8 million.

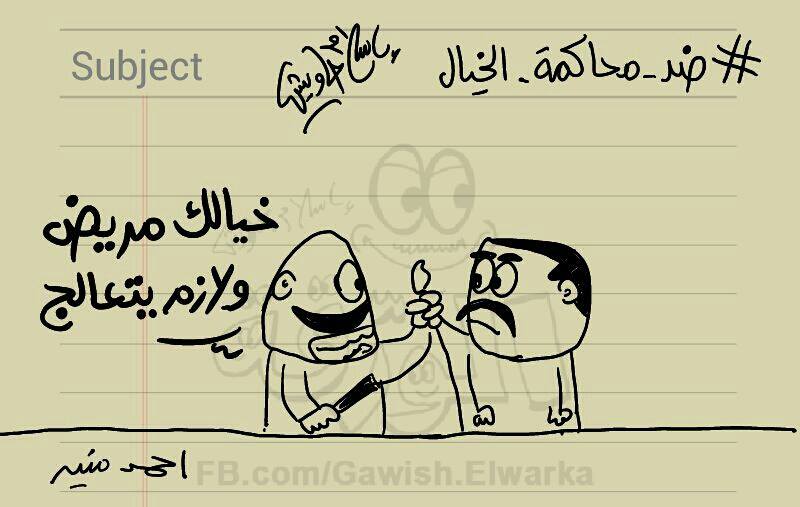

On February 11, the anniversary of Hosni Mubarak’s ouster, Gawish drew a gag about how free expression has contracted in the past five years. As Naji’s imprisonment made headlines ten days later, Gawish drew a cartoon using the popular hashtag Against the Trial of the Imagination. A thug threatens a man with a club as he grabs his shirt collar, saying: “Your imagination is sick, and it must undergo treatment.”