GAZIANTEP, Turkey — Abu Kamal stood behind the counter of his brightly lit shawarma shop, Awafis, along the city’s University Boulevard. With specks of gray poking through his short-cropped beard, he weaved among his staff with ease to meet the evening rush.

Although the shop was crowded, business was down when I visited in May. The predominantly Syrian clientele had less appetite than usual, angsty over the Turkish election that had precipitated a nativist backlash.

Abu Kamal was not particularly concerned, still thankful he had been able to relocate his restaurant after being displaced from his native Douma, in suburban Damascus. The area had been a major flashpoint between demonstrators, and later armed rebels, against the Syrian army in the early days of his country’s uprising.

The success of Awafis was due to Abu Kamal’s signature Damascene style for preparing all things poultry. It is a welcome departure in a culinary scene otherwise dominated by the meat-heavy titans of Gaziantep and Aleppo, from where most of the Syrians living here come. Even Turks frequent the restaurant, comprising a quarter of the customers, he told me, chest puffed out. Turks and Syrians alike swoon over his crème toum, the very unsubtle, but delicious, garlic sauce at the heart of his sandwich.

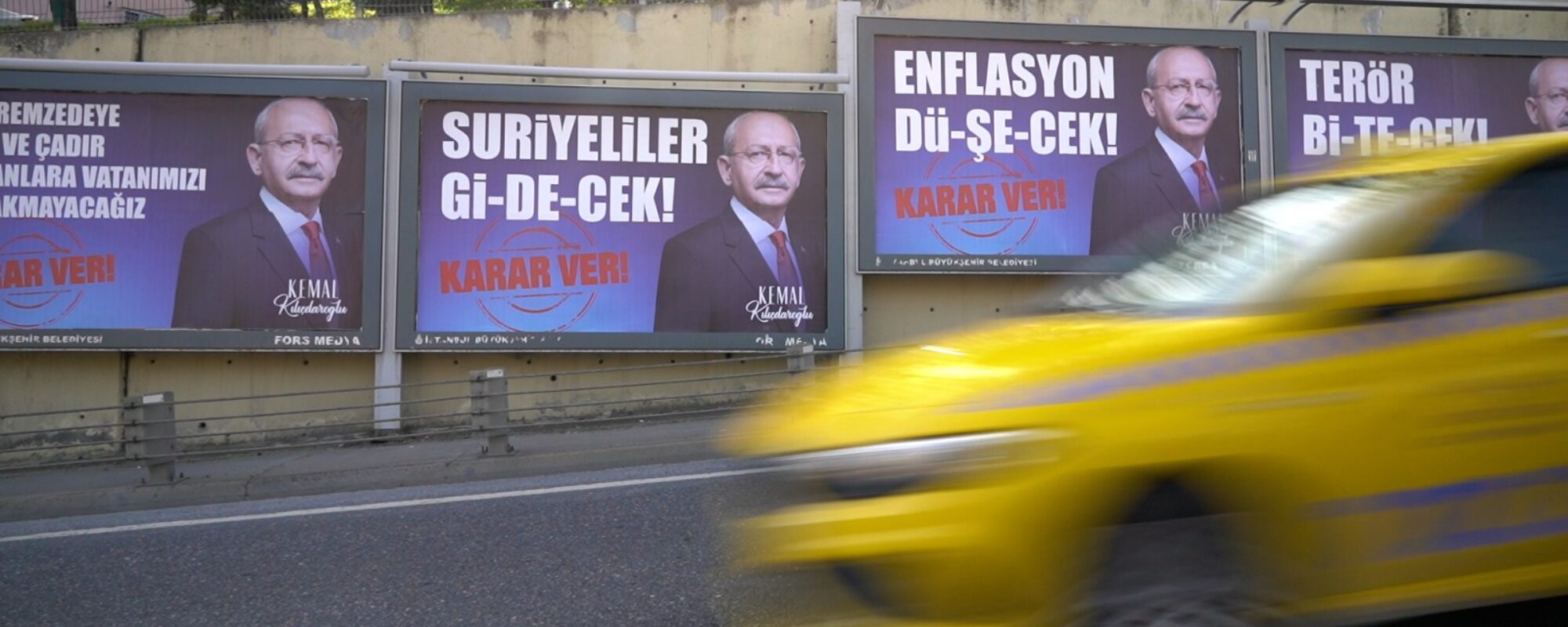

“I don’t face any racism here,” Abu Kamal said, despite campaign posters telling Syrians to go home.

“Because of the crème toum,” a customer butted in. “It’s too tasty to get mad.”

Already after the first round of the highly contested election, it was clear that refugees would be the ultimate losers, as Turkish ultra-nationalists brought jingoist rhetoric from the fringes to the center. A key takeaway from the election was that refugees are no longer wanted, even with President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s eventual victory in the second round. During the campaign, Erdogan appropriated some of the opposition’s discourse and moved away from his earlier, hospitable policies. The country’s migrant communities, with the Syrian diaspora at the center, now wait anxiously for the government to set its new course.

In Gaziantep, the looming restrictions on immigration could further restrict any benefits migration might bring to the city. Gaziantep had long been the darling of the United Nations, NGOs and journalists for its efforts to welcome in Syrians. The city’s mayor was a nominee for the 2016 Nobel Peace Prize for her role ameliorating the refugee crisis.

The industrial city of some two million near the border with Syria was one of the Turkish cities where the mass influx of Syrians had been felt most. But it remains unclear the extent to which the city over the past decade has become a melting pot, a mosaic, a mixing bowl or something entirely different.

* * *

Turkey today hosts more refugees than any country in the world. There are 3.6 million registered Syrians under “temporary protection,” as well as 320,000 “persons of concern” from other countries.

Erdogan opened the borders at the start of the Syrian war and in 2016 signed a deal with the European Union to prevent refugees from traveling to Europe in exchange for billions of dollars, visa-free access for Turkish citizens and the bloc’s promise to help resettle the refugees.

Gaziantep is closer to Aleppo—just 80 miles away in Syria—than to any major Turkish city. The two cities share kinship and longstanding ties, according to Ercan Kilic from the Sahinbey municipality in central Gaziantep Province, who works on migration issues.

“Our cultures are not different, living in the border area,” he said.

The city hosts more than half a million Syrian refugees, second in Turkey only to the slightly larger group in Istanbul. But while Istanbul absorbed the Syrians, constituting less than 4 percent of the megalopolis’s population, Gaziantep has struggled and today, more than one-fifth of its population now is Syrian.

Arabic can be heard in nearly every shop of the Irani bazar, which is the heart of the city’s Syrian community. Nadya, a sassy woman with spiky blonde hair, typically works as a translator for medical patients, as she speaks Arabic, Kurdish and Turkish—the three primary languages present in Gaziantep. Her work is drying up, she told me as we drank Nescafe on the street.

“The Iraqis went to Istanbul,” she said, referring to the earlier wave of displaced Iraqis, “and the Syrians learned Turkish.”

“Syrians created huge economic profits,” Mehmet Nuri Gultekin, a sociologist at Gaziantep University said. As an industrial city, Gaziantep initially thrived with the arrival of cheap labor.

Across the world, economists largely agree that immigration is beneficial to migrants and their hosts alike over the long term. But in Gaziantep, the idea that employment acts as a powerful driver for integration and social cohesion has been less apparent.

“Sure, there are some well-educated, middle-class business types who interact with Turks,” Gultekin told me in his office overlooking the sprawling campus. But he honed in on the “residue”—poor Syrian laborers doing the heavy lifting to boost the local economy while living in their own parallel society.

In theory, daily interactions should offer opportunities for integration. But this has not been the case here, he explained. Although these poor Syrians live in close proximity to the Turkish community, the social barriers separating them could hardly be more pronounced, he argued.

Migration barriers are proving self-defeating. Heavy restrictions remain for Syrian refugees regarding employment and movement, and they act as a drag on the overall boost migration typically brings, Gultekin argued.

Despite the uncertainty, Gultekin was sure of one thing: Most Syrians will remain.

“You can’t reverse social movements,” he said with conviction.

Although he was sure they would stay, he was skeptical about their prospects for integration.

* * *

I rode out of the city with a Syrian driver toward one of the city’s zoned industrial centers as he pointed out some of the changes brought on by the diaspora.

“All these are new buildings by Syrian money,” he said, speaking of the apartment blocks that fanned out along the highway.

For sure, such transformations were already in motion by the time the Syrians arrived en masse. Gaziantep’s development had been promoted since the mid-1980s and grew further with the influx of investment into the conservative city after Erdogan and his infrastructure-minded Justice and Development Party came to power.

But Syrian migration, and the international humanitarian aid that followed, made the city the epicenter for the new Syrian diaspora in Turkey and tugged the country’s export-oriented economy further southeast.

The economic contribution of Syrians could be seen by the businesses moving across the border in addition to the influx of Syrian labor. Ali Kaplan, a Gaziantep native who manages Erkaplan Carpets, recognized that fact.

“It’s easier to find workers now. Syrians brought benefits, and they brought money into Antep,” he explained, using the local nickname for Gaziantep, in his dazzlingly bright showroom, with mirrors on the ceiling to display the carpets from all angles. But he also saw how Syrians opened their own businesses and created competition, pulling away foreign customers–particularly Arabic-speakers–from his company.

While some just compete with Turks, others employ them as well. Mohammad, who asked that only his first name be used because of caution for his businesses, sat across from the large wooden desk in his office in the industrial park. With tiny tufts of gray hair on his head and upper lip, he recounted relocating in the early days of the Syrian uprising. He initially started a series of small bakeries making traditional round bread, but then shifted to producing bread bags and eventually all types of plastic products. Today, he has more than 100 workers, both Turks and Syrians.

“Turks are very industrious. The changes here are not just due to us,” Mohammad said.

But he credited Syrians with injecting additional capital into the city, as well as creating a livelier atmosphere. He recalled how when he first arrived, he had brought a portable DVD player to watch movies because everything shut down early. But now the streets are busier, even resembling Istanbul, he said, not completely exaggerating.

Still, the political fallout from the election left him unsettled.

“I have Turkish citizenship, a nice home and a business,” he continued. “But my kid is asked by his classmates if we had a bathroom back in Syria.”

He referenced a Syrian caught in the February 6 earthquake rubble refusing to speak because he feared that if rescuers knew he was Syrian, they might stop their efforts.

“All I hear about is sending Syrians back. How could you feel secure?” Mohammad concluded.

One of the largest spaces in the business park is run by Besler Group, owner of the main flour mill in Turkey.

Veysel Sezgin, who works in sales, was torn about the Syrians. As an employer, he had benefited from the economic growth. But as a citizen, he felt his hometown had been unable to keep pace with the population bulge.

“Now if there are three people in the hospital, two of them are Syrian,” he said.

* * *

Back in the city center, I visited the office of a Syrian beverage baron named Ahmed Jabar. He offered me an energy drink, one of many his family produces. With a big smile and red power tie, he clapped his hands loudly after I noted how Bison energy drink was the best I could recall having (Disclaimer: I can’t remember the last time I had one.)

Jabar went on to tell me how Turkish society should be more appreciative of the contributions from Syrians.

“We work 27 hours a day, and then we spend that money,” he guffawed, clapping his hands together again. “We Syrians don’t save.”

There is a perception among Gaziantep locals that Syrians operate in a closed economy, meaning that their spending remains mostly within the Syrian community. But few stop to think about what is driving this habit.

I saw this in action up close later that evening over meze and grilled meats with Anas Abdulwali, a 31-year-old Syrian professional who wanted out of Turkey.

During our conversation, the reality for Syrians in Gaziantep—one in which fear drives them to minimize interactions with Turks—emerged clearly. Abdulwali feared he could be deported at any time, and was reminded of that constantly—for example, a Turkish driver once alluded to it after he was the one at fault in a minor traffic accident.

“We aren’t seen as humans here. We are seen only as Sureyli,” the Turkish word for Syrians that was often evoked as a boogeyman by all sides during the heated election campaigns.

Turkish politics have pushed Syrians to become even more insular. To avoid problems, Abdulwali divided his time between working at a Syrian-owned firm and spending time with his Syrian friends at cafes and restaurants run by his exiled compatriots. He was preparing to leave Turkey the following month for good.

Social tensions were pushing some of the best and brightest to find ways to leave.

“Everyone wants to go except those who do not have the luxury to leave,” Duaa, another Syrian I met, who also asked only her first name be used due to the fraught political climate, told me at a Syrian-owned café. She hoped to hear back any day about her application for a master’s degree program in the United Kingdom.

* * *

In the immigration canon, no experience is more sacrosanct than the pattern that the children of poor migrants typically pay back their parents’ debt to society. A 2017 report found that second-generation immigrants worldwide were upwardly mobile and strong contributors to their economies.

This phenomenon could be particularly important for Turkey, a country with an aging labor force that faces an uncertain economic future. In Gaziantep, half of the Syrian community is under 18, a great opportunity to meet the city’s growing economic needs. For most of these youths, Syria is more a narrative than a lived experience.

As the dinner rush at Awafis began to ebb, Abu Kamal joined me across the street for a coffee. He excitedly told me how the first of his three sons would be going to a Turkish university in the fall.

“I want three doctors,” he replied when I asked which one would take over his restaurant.

The migratory experience of Abu Kamal and his family is far from unique. Globally, the children of immigrants are less likely than their parents to own their own businesses, and his sons will be better placed to pursue careers less grueling than food service. Raised and educated in Turkey, his children can expect greater social mobility and greater inclusion in the mainstream economy.

If such mobility and inclusion are cultivated rather than restricted by nativist politics, the social and economic promise of Abu Kamal’s sons and all the others like them can be borne out for the greater good. But if the atmosphere that predominated during the recent election continues, Turkey could remain focused on the short-term burdens of migration instead of building toward its future blessings.

Top photo: Campaign posters along the highway read “Syrians will go”