Skyrocketing food and energy prices fueled by the Covid pandemic, climate change disruptions and Russia’s war in Ukraine continue to stress consumers around the world, prompting protests and social unrest. Even in the United States, although prices have retreated from peak inflation levels in mid-2022, they were still up 3.1 percent last month compared to the previous year.

Roughly two-thirds of Americans were reported feeling gloomy about the economy despite healthy economic growth and a historically low unemployment rate. A recent government report also indicates that the pandemic widened the wealth gap between whites and non-whites. The public frustration is likely to play a significant role in the November elections.

Meanwhile, the United Kingdom and Japan have fallen into recession as their economies shrank for two consecutive quarters. Japan gave up its spot as the world’s third-largest economy to Germany, which is also struggling.

Surging inflation has affected other countries in Asia too, pushing nearly 70 million people into extreme poverty. ICWA fellows on the ground in South Korea and Taiwan report that price pressures are a major focus of political discourse, affecting young people’s future plans and perceptions of success.

South Korea

Many of South Korea’s popular cultural exports, dubbed the “Korean wave,” critique the country’s growing wealth disparity. From Bong Joon-ho’s Academy Award-winning 2019 film “Parasite,” to the 2012 hit K-pop single “Gangnam Style,” artists are responding to a system of inequality in which the richest 20 percent owns almost half the country’s assets, 64 times the average wealth of the bottom 20 percent.

Levinson fellow Prachi Vidwans points to two competing narratives of social mobility. First, an awareness that true “success”—defined by wealth and comfort—is available to only a select few. “It’s common to refer to classes using ‘spoons’ in Korea,” she said. “If you’re not born with a gold spoon, if you have a wood, steel or dirt spoon, the odds of achieving success are against you.”

Still, many believe people can achieve success through education, that by studying hard enough, they might be able to overcome the circumstances of their birth.

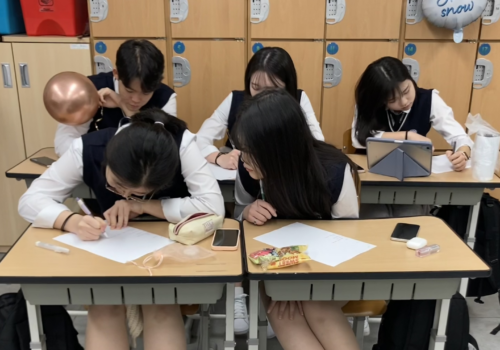

But exorbitant education fees are pushing such merit-based advancement out of reach for increasing numbers and contributing to South Korea’s declining birth rate, the world’s lowest. As Prachi wrote in a recent dispatch on the education system, families spent a record $20 billion on private education in 2022, as much or more per month as they do on food and housing, according to the Korea Times.

Given those expenses, many women are deciding not to marry or have children. “Before I came to South Korea, I mostly understood the country’s low birth rate issue as being related to gender politics,” Prachi said. “That’s part of it, but broader economic inequality is a tremendous part of the story, too.”

Meanwhile, office workers keep punishingly long hours, and many shopowners run several businesses simultaneously to make ends meet. People often spend their weekends reading self-help and professional development books to improve at work, Prachi notes. Demoralized and overworked, many young people wonder if they want the same future for their children.

Korean politicians are actively debating solutions to these problems, and the high cost of living is set to be one of the major issues in April’s legislative election. However, Prachi believes that addressing the “massive, foundational problems” behind economic inequality will take incredible will, time and resources.

Taiwan

Inflation and cost of living were on many voters’ minds during Taiwan’s January elections. Democratic Progressive Party President Tsai Ing-wen signed a new minimum wage act into law a month before the elections. However, huge dissatisfaction with low wage growth and high rent costs remains, contributing to the rise of The Taiwan People’s Party, a center-left third party.

David Mixner LGBTQ+ fellow Edric Huang described the financial pressure many feel in what he called Taipei’s “hustle culture,” where people are encouraged to work nonstop and overtime is common. “When I talk to local friends about my career in NGOs and social impact, they are simultaneously impressed and bewildered because often all they can focus on is working to feel like they can rent or buy their own place, or raise a family,” he said.

A 2023 poll found that 90 percent of office workers were unhappy with their wages, and three-fourths hadn’t received a raise that year. Many believe salaries are not keeping up with rising prices, and seek shortcuts to make ends meet. Given high rental costs and a lack of regulation, most people in Taipei still live with their families or in shared housing by necessity.

For LGBTQ+ people, discrimination can make economic situations more dire and leave critical needs unaddressed. In a recent dispatch, Edric identified highly prohibitive costs as a major reason why some 88 percent of transgender Taiwanese have not yet undergone gender affirmation surgery. The surgery is often not covered by the National Health Insurance System and costs at least $5,000—on average four months’ wages.

Although Taiwan has a strong higher education system, Edric observes that limited job prospects often push those who can seek opportunities abroad to do so, even though most would like to stay in Taiwan. “In this labor market, the cost-of-living crisis is very real,” he said.

The general resentment and insecurity felt in Taiwan and South Korea reflect feelings of people around the world, contributing to an atmosphere of instability during a year of consequential elections in many countries.