BERLIN — When I was meeting with the Russian journalist Masha Borzunova outside a coffee shop in Berlin’s lush Schillerkiez neighborhood, a young boy stopped in his tracks on seeing her. The boy’s father—a German who spoke a bit of Russian—politely interrupted our interview to tell Borzunova that his wife, a former Belarusian journalist, watches her weekly segments together with their son. The boy gleefully acquired an autograph.

Dressed in a leather jacket, she had a forthright manner. “People often approach me on the streets now,” she said.

While Borzunova’s online programs—one airs on the German-French broadcasting network Arte.TV and another she publishes on her Russian-language YouTube channel—deal with subjects that may not be suitable for a boy who looks about 9 (war, propaganda and political repression), her upbeat and spunky on-camera persona has attracted a cross-generational audience.

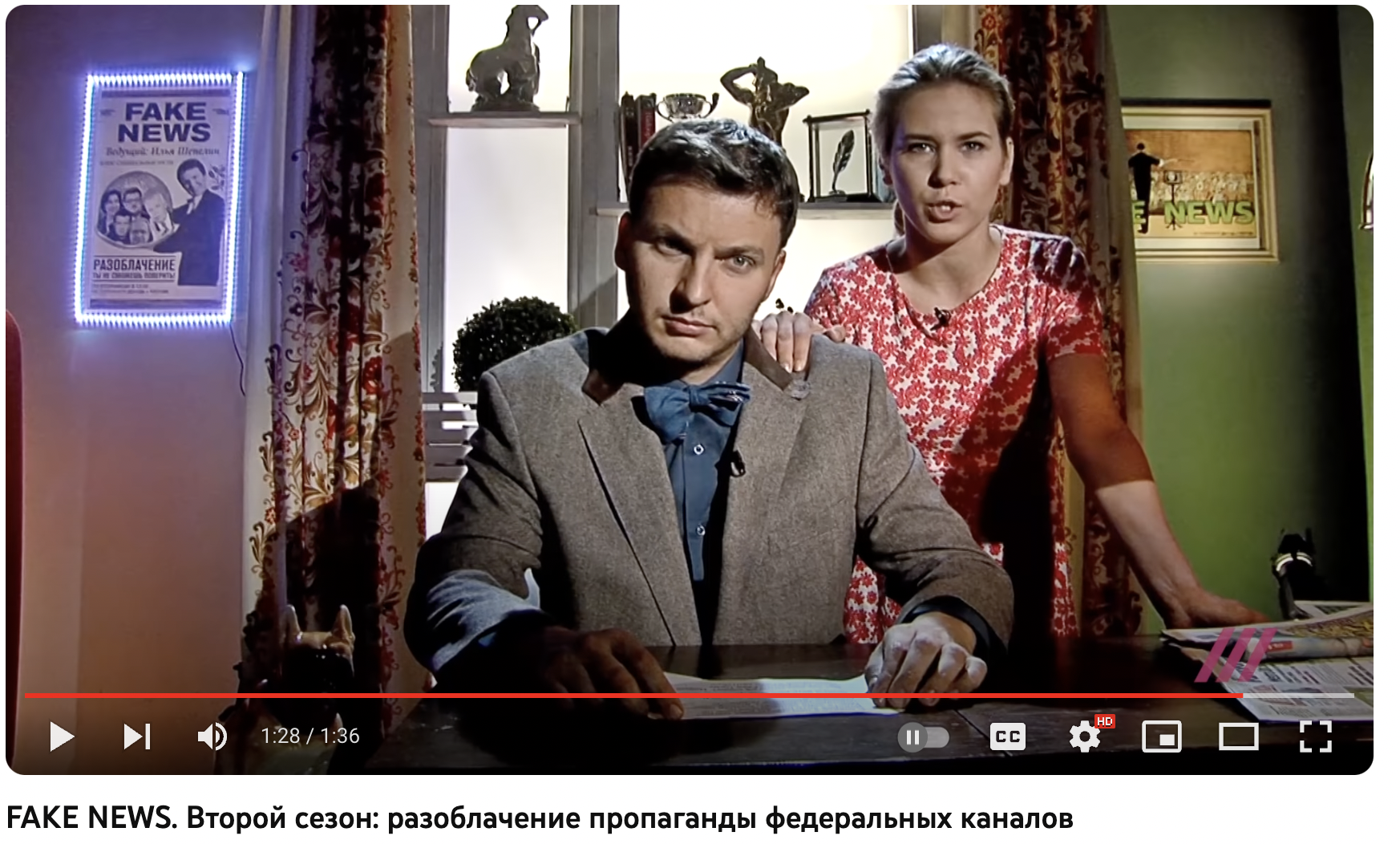

In the years leading to the war, Borzunova, 28, rose to prominence as co-host of “Fake News,” a program devoted to the analysis of Russian propaganda that featured on the independent Russian TV Dozhd (Rain) channel. Together with the journalist Ilya Shepelin—who now resides in Vilnius—she would deconstruct absurd news items pushed by Russian propaganda in playful layman’s terms.

But Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and new draconian restrictions that followed forced Borzunova and countless other journalists out of the country. A tumultuous year in exile threw further hurdles at her career.

Now, after nearly a year in Germany, she appears to have hit her stride again. She explains to her new local audience how Vladimir Putin’s propaganda machine operates along with the Kremlin mechanisms enabling the Russian president to stay in power.

While most of her colleagues continue producing work for their traditional audiences, Borzuonva is an example of how exiled Russian journalists can tailor their content for a more diverse viewership, and evidence that demand for Russians reporting on Russia is growing in Europe.

The Russian school of journalism

Borzunova was raised in the Moscow suburb of Podolsk by parents who were both veterinarians. She initially wanted to follow in their footsteps but the praise she received at an after-school journalism workshop in 10th grade compelled her to pursue a different path.

Growing up in a “a small, simple city,” she had little grasp on politics, she says, and was more intrigued by the technical aspects of the job. But the communications department of the prestigious Moscow’s School of Higher Economics (HSE), which she attended for her bachelor’s degree from 2011 to 2015, was still staffed with veteran reporters from the days of Russia’s free press, who instilled in her the idea of “journalism as a duty.”

There, her “world began to open,” as she learned about cases like the assassination of journalist Anna Politkovskaya, and began to understand the repressive system that ruled in her country.

Her entry into the university also coincided with protests in 2011, the largest anti-government movement Russia had seen since President Vladimir Putin came to power at the turn of the century. The political tide was a topic of lively discussion even in the classroom settings.

Her first university project was a short documentary about the protests, something she says would be impossible to produce at the university just a few years later. During her sophomore year at HSE she began an internship at Dozhd TV, and her professors allowed her to submit her professional reportages as school assignments.

“We were probably one of the last graduating classes to experience such freedom, it started getting worse and worse,” she said. “Some professors would get fired, others would leave.” During her final year, the former communications department dean, Anna Kachkaeva, a well-known former reporter for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, was replaced by Andrei Bystritsky, a journalist who had worked for propaganda radio stations and is now sanctioned in the West.

“I remember at the graduation ceremony how our professors were whispering to us that we were leaving at the right time,” Borzunova said.

Since it opened its doors in the aftermath of the Soviet collapse, the Higher School of Economics had always boasted a progressive faculty. Its professors tried to resist democratic backsliding until the very end. But in recent years, the appointment of new, Kremlin-loyal rectors and deans has restricted the environment for professors with dissenting opinions.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine marked the end of HSE’s era as a liberal bastion. After its current rector publicly declared his support for the invasion, many professors were forced out, while Western academic associations cut their ties with the university.

Borzunova continued working for Dozhd as a court reporter after graduating, covering high-profile cases against opponents of the Kremlin regime. Her predecessor in the job said she saw in her enough of a “nerd” who was up to the task of covering the jargon-heavy intricacies and nuances of the judicial system.

Digging through legal documents and reporting from outside courtrooms, Borzunova covered a trumped-up criminal case against the now-jailed opposition politician Alexei Navalny, an unresolved investigation into the assassination of the opposition leader Boris Nemtsov, and the show trial of Oleg Sentsov, a Crimean-Ukrainian filmmaker who was jailed for “plotting acts of terrorism” before his 2019 release through a prisoner swap. She soon transitioned from written reporting to shooting her own reportages about how corruption enabled the Kremlin to weaponize the judicial system against its opponents.

For Borzunova, Dozhd was the “ultimate school for journalists” who worked as “jacks of all trades, shooting and editing their own content, and writing their own scripts.”

In 2018, she was brought onto the program “Fake News” to join then-host Shepelin. “When we started ‘Fake News,’ it was clear that the extent of [government] lies was so massive, we needed to underscore these lies and dispel them,” she said of the program. “[Shepelin and I] would joke that watching endless reels of [Vladimir] Solovyov [a chief Russian propagandist] daily was our ardor.”

Characterizing the ethos of “Fake News,” Shepelin, 35, described a Russian propaganda news item that inspired the creation of the program. In honor of Vladimir Putin’s 65th birthday, a restaurant in New York City was said to have served a limited-edition hamburger whose weight—1952 grams—corresponded to his birth year.

The independent Russian journalist Alexey Kovalev noticed that Russian state-controlled media listed the weight of the burger using that metric measurement instead of US customary units—something a New York restaurant would almost certainly never do. That compelled him to produce an investigative piece debunking the story altogether.

I don’t think Russian people are somehow special in their alleged absence of critical thinking. There are many examples in history where propaganda worked.

The comically absurd nature of the story subsequently inspired Dozhd’s editorial team to create an entire program devoted to calling out such propaganda items.

The show’s conception also coincided with the start of Donald Trump’s presidency. “‘Fake news’ isn’t a term used colloquially to actually mean misinformation,” Shelepin said. “It was used by politicians like Trump and the Russian state to debase news items that discredited them or didn’t fit with their agenda.”

Different departures

One week after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Kremlin passed a “fake news law” prohibiting information it deemed unreliable. At the time, Shepelin happened to be abroad, vacationing in Georgia.

“When the war started, I would sleep for one hour a night, doom scroll and post fiery criticisms of the Russian government on Twitter,” he told me outside a restaurant in Vilnius, a pair of round glasses underneath his curly head of hair.

Dozhd was still trying to adhere to the new set of guidelines the government media watchdog Roskomnadzor put in place to avoid blockage in Russia. “Obviously, [my inflammatory] online outbursts did not align with Dozhd’s policy,” he said.

It prompted him to send a letter of resignation. “I wasn’t in the state to produce shows anymore, especially given the constraints, and I had no intention whatsoever to return to Russia,” he said. A few days later, the chair of the imprisoned opposition leader Alexei Navalny’s Anticorruption Foundation (FBK), Maria Pevchikh, invited Shepelin to work for its YouTube media outlet, Popularnaya Politika (Popular Politics).

“When I heard that Navalny himself asked his lawyer that FBK consider me for the job, I couldn’t resist,” he said. “Navalny is sitting in prison because of our sins, and suddenly I had the opportunity to work for him.”

Soon after, Shepelin moved to the Lithuanian capital Vilnius, where the Navalny organization was already headquartered, and where he continues his exposure of Russian propaganda through Popular Politics and his own YouTube channel.

When we met for pizza in the city, he, too, was approached by a fan of Belarusian origin. The middle-aged woman jokingly introduced herself as a “political prostitute”—President Aleksander Lukashenko’s derogatory name for protestors who fled Belarus from fear of persecution—before taking a selfie with him.

Sometime later, another less desirable passerby stopped to stare at us. According to Shepelin, the man was a self-proclaimed pro-Ukrainian activist of Russian origin who had doused the leading Russian satirist Viktor Shenderovich with ketchup some weeks earlier in Vilnius. “We’re lucky that he probably didn’t have ketchup on him,” Shepelin quipped after the man left.

For Borzunova, Shepelin’s departure from “Fake News” meant all the work would now land on her shoulders. “She was understandably angry with me, and we didn’t speak for some time,” he said. However, the two recently reunited on camera as part of a “Solidarity Marathon,” an online donation drive hosted by several independent Russian media outlets to raise money for political prisoners.

During the week following the invasion, Borzunova, who was still in Moscow, would work “day and night” to preserve her sanity, she said. For one of her first post-war reportages, she interviewed the relatives of Russian soldiers captured by the Ukrainian army. “The Ukrainian government released photographs of these captive soldiers, which Russian state media claimed were fake,” she said. A father of one of the soldiers confirmed one of the photographs was of his son.

After conversations among her editors, Dozhd eventually aired her segment despite its clear contradiction of the state’s initial narrative that Russian soldiers were not engaged in direct combat and only entering Ukrainian territories for a “training exercise.” It was a dangerous move for the station.

“I understood that [our time here] was limited, and that we’re sitting on our suitcases,” she said, using a Russian term to describe a temporary stay. “I determined for myself that if Dozhd were blocked, that would be my red line” for emigrating. On March 1, 2022, the government barred access to Dozhd’s website, and three days later, introduced new draconian wartime censorship laws.

Departure still proved a major ethical dilemma for Borzunova. Only after circular conversations with her therapist and friends did she eventually decide she would be more useful abroad, where she could continue her work unhindered.

“Despite the risks, I initially felt that for me personally it was important to remain and cover the country from within,” she said. “I felt at the time that departure was a sign of weakness and resignation.” Even before the war, journalists had already been debating whether a full-scale invasion, and by extension, their emigration, were on the horizon.

She remembered urging Belarusian colleagues to flee their own country in the wake of Lukashenko’s earlier brutal crackdown on Belarusian civil society. “I thought, why was I not applying the same standards to myself?” she said.

“I understand why for politicians like Alexei Navalny it’s important to make the sacrifice of remaining in the country and facing prison,” she added. “But for journalists, such a sacrifice would render our work useless—no one’s life would improve if I were suddenly jailed and couldn’t report anymore.”

A day after the new censorship laws were enacted, Borzunova flew from Moscow to Istanbul. A short period without work—when Dozhd temporarily suspended operations to adapt to its new reality—proved psychologically taxing.

“I was sitting in a haze and slowly all this stress was catching up to me,” she said. Eventually, the realization that departure would be “for a long time” sank in.

Her migration route eventually brought her to Berlin by way of Tbilisi and Riga, where Dozhd had moved headquarters.

Shortly after Borzunova’s leaving, the Russian government labeled her a “foreign agent,” which she calls an injustice. “I love my country much more than those people who labeled me.”

She soon learned the formal reason for her designation, a money transfer from the Wall Street Journal correspondent Evan Gershkovich, a close American friend whom the Russian authorities arrested a year later in March 2023. “That obviously wasn’t the real reason—they assigned me the label because of my work,” she said.

On numerous occasions throughout our conversation, we brought up Gershkovich, who is in pre-trial detention in Moscow on bogus espionage charges. After our interview, we were joined at the cafe by Western correspondents who are also friends of Gershkovich and continue covering Russia from afar. Their conversations about the ethics of returning concluded with the same question: “What would Evan think?”

The consensus was that he would strongly disapprove of any journalist’s decision to return.

New audiences in exile

Several months after Borzunova’s departure, Arte.TV offered her a monthly show. Coupled with grievances with Dozhd on which she would not elaborate, it prompted her departure from the Russian station.

“I worked for several different [iterations] of Dozhd throughout my nine years there,” she said. “I realized that the same Dozhd I joined so long ago was no more. But I still wish them the best, they launched my career.”

While she admits the tone of her program “Fake News” may have failed to effectively appeal to its intended audiences—Russians who consume propaganda—she still does not dismiss the value of her work there. “It’s important that we captured these moments so they can later be analyzed by historians to understand why this happened,” she said.

She continues targeting a Russian-speaking audience through her YouTube channel, which she runs with the help of hired editors and videographers. Ads bring in some revenue.

When producing her YouTube episodes, she tries to remain cognizant of the fact that much of her audience in Russia may be people who choose to pursue the “defense mechanism” of shutting out any information about the war. “I try to listen to my followers, to understand their mode of thinking,” she said.

On her Arte.TV programs, Borzunova tailors content to Western viewers, often explaining thoroughly how the Russian state and society operate. She recently produced a segment about how the Church has become a mouthpiece to justify the war.

“People in Europe are always asking the question—how is this possible?” she said of the war and Putin’s regime in general. “I try to remind them that propaganda works and explain how it works in Russia, and the conditions that allowed this war to become possible.”

The efficacy of propaganda

With hindsight, Borzunova believes Russian propaganda had been readying the public for war for some time. “It tries to interfere with your ability to ask questions and think logically,” she said. “For years, it had been yelling about Nazis in Ukraine rather than internal problems.”

Russians have been “constantly told that we were surrounded by enemies, and that we needed to defend ourselves.” That “brought current events to their logical conclusion.”

The government’s clampdown on independent media enabled state-controlled outlets to become the only source of information for millions across the country.

“It’s much easier to turn on the TV than seek answers elsewhere,” she said. “Propaganda is easy, it gives you an immediate answer.” A sign in Russian reminding her audiences to “Turn off your TVs” hangs on the backdrop of her Russian YouTube show.

Over the last decade, Russian propaganda tended to employ increasingly abrasive tones. Chief propagandists such as Olga Skabeeva and Vladimir Solovyov often shout on their segments, attacking opponents of the regime with designations such as “enemies of the state” and “traitors,” and weaponizing paranoia-laden narratives about enemies abroad.

Since the start of the war, it has become “even more aggressive,” Borzunova says. “They do not even try to explain anything anymore, they just yell slogans and say things matter-of-factly.” Lately, however, she has noticed many propagandists have also begun to express genuine fear, especially in their coverage of moments of domestic disorder like the failed mutiny of Yevgeny Prigozhin, the head of the Wagner paramilitary group who was killed in a suspicious plane crash last month.

Borzunova continues to maintain a light, instructive and sometimes playful tone in her YouTube segments, which expose and mock the logical discrepancies in state-controlled news. But consuming such hateful content daily is taxing. “Especially after the war, you begin to realize that these are no longer just words—you understand that behind them are deaths and lives destroyed, including your own,” she said. “But this is my job.”

While it’s designed for a specific audience, Russian propaganda is not unique in its efficacy, Borzunova believes.

“It’s not news that propaganda works, I don’t think Russian people are somehow special in their alleged absence of critical thinking,” she said. “There are many examples in history where propaganda worked,” she added, gesturing to the surrounding streets of Berlin.

Perhaps that’s why Borzunova has found such an eager audience in Germany, a country that recovered from its own dictatorship. A day before we met, her Arte.TV segment on Prigozhin’s mutiny was the number one trending YouTube video in the country.

“At times, I do feel like I came to the right place to continue my work,” she said, “that the local historical context makes my work even more compelling.”

Top photo: Borzunova meets a young fan in Berlin