VILNIUS — “Frustration” was the keyword of the 2023 NATO Summit, which took place in mid-July here in the Lithuanian capital. Photos of a lone Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, standing stage right while the leaders of the Free World happily mingled in the center, came to symbolize Ukraine’s reaction to not being granted a firm promise of rapid accession to the military alliance.

Ruslan Shaveddinov, a 27-year-old exiled Russian opposition activist and former right-hand man of the imprisoned political leader Alexei Navalny, also expressed frustration as he argued that European governments were failing to impose sufficiently stringent sanctions on Russians responsible for the war.

Over a bowl of cold Lithuanian beetroot soup at a restaurant less than a mile away from where NATO delegations were deliberating over Ukraine’s membership status, Shaveddinov vented to me about how the West was dragging its feet on depriving Kremlin elites of their European assets.

“European bureaucracy is incredibly rigid and much too cautious,” he said.

His scruffy beard did little to cover his boyish features. On his right arm, a small stick-and-poke tattoo of a cartoonish bear squiggled above his Apple watch.

“How can a Russian government official on a three-million-ruble [$35,000] annual salary own a villa in Spain worth $10 million?” he asked. “Make it make sense!”

Shaveddinov is continuing his work as project manager for Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) in Vilnius, which has become a major hub for Russian and Belarusian civil society activists over the last two years. The organization began sending its hundreds of employees abroad after the Russian government deemed it an “extremist organization” in 2021.

Perceived by many to be Russia’s main political opposition group, FBK is now registered as an NGO in Lithuania and operates free of the draconian constraints that were hampering its work back home.

In an office at an undisclosed location in the city, Shaveddinov and his team continue their battle against Russian President Vladimir Putin’s government, undaunted by criticism, the threat of Russian security agents or the kind of long prison term recently handed down to Navalny himself.

FBK continues issuing its trademark investigative videos, which are as widely anticipated by audiences as new HBO shows in the West. With impressive production values and a sarcastic narrative style, many of the productions expose the vast European and domestic assets of Kremlin insiders and their families.

Concurrently, FBK activists are working on their List of Bribetakers and Warmongers—a database of Putin’s “accomplices” whom the FBK argues deserve to be sanctioned by the West.

It has been an especially rocky road, however. Since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the organization has endured a number of reputational blunders.

Some have criticized it for inconsistencies in selecting who deserves a place on its list. Other, pro-Ukrainian, voices argue FBK does not have their country’s interests in mind and that its ambition to create a “prosperous and wonderful Russia of the future” does not confront the threat from Moscow’s imperialistic tendencies.

FBK’s leadership often appears not to handle such criticism well. All too often, senior figures like Leonid Volkov, Maria Pevchikh and Lyubov Sobol take to Twitter to rebut criticism with statements critics deem controversial.

Such moments, which alienate the movement from some of its would-be supporters, create the impression that it is not equipped to take on the role of replacing Putin’s regime.

Add Alexei Navalny’s latest sentencing in Russia—additional convictions on extremism charges that brought his total prison sentence to 19 years, which the opposition leader referred to as a “Stalinist term”—and the organization sometimes begins to look like sinking ship from the outside.

But Shaveddinov remains optimistic, perhaps due to his relative youth and reluctance to engage in Twitter debates, keeping his head down and doing his work.

“We have all undergone countless searches and arrests,” he said. “All of this pressure from the authorities has united us to such a degree that inside our collective, there are no problems.”

“We are all very different in how we choose to behave publicly,” he added, “but we are united by one common goal––to depose Vladimir Putin and his cronies and to establish a free and democratic state.”

Even in these dark times, Navalny’s youngest trusted lieutenant may offer a direction for the organization’s future.

A career in opposition politics

Shaveddinov’s hometown of Istra—“a typical, poverty-stricken suburb of Moscow where the heads of government corporations and state officials own huge swathes of land”—inspired his early ideological convictions.

As a university student in Moscow in the 2010s, he would regularly read Navalny’s blog posts on the then-popular LiveJournal blogging website. Prior to the opposition’s mass migration to YouTube, LiveJournal was a key platform for public intellectuals, independent journalists and political bloggers.

In those posts, where he published photographs of lavish estates owned by Russian government officials, Navalny coined his iconic “party of crooks and thieves” label for Putin’s ruling United Russia Party, which exercises a stranglehold on all levels of government. From the beginning of his political career, his agenda—and, subsequently, the FBK’s—has remained the same: to demonstrate to the public that corrupt Kremlin officials are harming its interests by siphoning off government money and resources for their personal enrichment.

“His anti-corruption investigations, in which he spoke about important topics with a very clear tone and accessible language, resonated with me,” Shaveddinov told me.

He first joined Navalny’s team as a volunteer for his 2013 Moscow mayoral campaign. Despite government-created obstacles, the opposition leader eventually came in second place with a surprising 27 percent vote.

We are fueled by even more rage, and will do everything in our power to put an end to this regime.

Shaveddinov remained with the organization, climbing its ranks over the years.

“Navalny was always able to evolve in his ability to instrumentalize modern technology,” he said, citing the creation of Navalny-Live, FBK’s main YouTube channel.

“Because we were always blacklisted in the country and barred from TV, YouTube became the main instrument with which we could reach an audience of millions.”

In addition to its investigations, FBK also engaged in on-the-ground, grassroots political organizing. Shaveddinov accompanied Navalny on countless trips across the country, when they would train volunteers and develop strategies to galvanize the public to protest and vote.

“It was important for us to dispel the myth that the liberal opposition sits inside Moscow’s Garden Ring [road circling the center] and discusses ‘liberal values,’” Shaveddinov said. “Vladimir Putin had destroyed public demonstrations in Russia. There was a whole generation that grew up without seeing public politics, and we brought that back to the country.”

Among the many schemes the Navalny organization invented to try to break Putin’s grip on power was “smart voting,” an electoral strategy that sought to unseat United Russia in local and regional elections beginning in 2018 by focusing the anti-Putin vote.

Shaveddinov and other FBK activists conducted thorough studies of all candidates running independently or from other parties, even those they considered “systemic opposition,” the term for the three national parties that nominally oppose United Russia but actually vote in unison with the ruling party on major issues and share the spoils of political power.

They would then urge voters to cast ballots for the candidates with the best chance of defeating their United Russia rivals, even if they represented the Communist Party or the nationalist Liberal Democratic Party of Russia.

The goal, in many cases, was to replace “one very unpleasant politician with a slightly less unpleasant one who was against Putin,” Shaveddinov explained.

In 2019, FBK took this tactic to the Moscow City Duma elections, successfully “casting out 40 percent of United Russia politicians from the city’s administration” and seriously cutting into, but not breaking, its voting majority in the municipal legislature.

Despite the odds, FBK proved that some success was possible even under Putin’s deeply rigged authoritarian system.

But it also put targets on their heads, and Shaveddinov was one of the first to find himself in the government’s crosshairs. The authorities detained him seven times that fall before delivering a final blow in December.

One frosty winter afternoon in Moscow, masked security officers barged into Shaveddinov’s apartment brandishing assault rifles. They forced him to the ground, snapped handcuffs around his wrists and dragged him off to be interrogated.

Before he realized what crime he was being charged with, he was escorted onto a commercial flight headed to the northern port city of Arkhangelsk, still handcuffed.

“It was like a scene in a film; I was sitting in the last row of a full plane in handcuffs, with masked officers on either side of me,” he said.

Upon eventually arriving at a military base on Novaya Zemlya, an Arctic archipelago the Soviet authorities once used as a nuclear testing site, Shaveddinov learned he would spend a year as a conscripted soldier in the Russian army. Military service is mandatory in Russia for all men aged 18 to 27, but, like many from the country’s major cities, Shaveddinov had dodged the draft through a medical exemption.

As a form of punishment, the authorities decided to forcibly conscript him, effectively abducting him and sending him into what he calls “forced exile.”

After weeks of being filmed by Russian state media showing audiences how officials “discipline” a member of the Navalny organization, Shaveddinov was sent to an even more remote location at the very edge of the archipelago that could be reached only by helicopter.

A military hut known as a “barrel” nestling in the snow next to an emergency landing pad was the only shelter on the wind-swept tundra. Polar bears stalked the grounds nearby.

Shaveddinov and three fellow soldiers would melt ice for water. Once every two weeks, a helicopter would bring them food and letters—the only connection with the outside world.

During his year of forced conscription, the outside world turned upside down.

The Covid-19 pandemic forced many countries into lockdown, and Navalny survived a poisoning attempt that he linked to Russian security agents acting at Putin’s behest. Shaveddinov returned to Moscow just in time to greet Navalny at the airport for his own triumphant and widely televised return to Russia from medical treatment in Germany in January 2021.

The authorities immediately arrested Navalny, who has been in custody since, and then set their sights on his organizations. FBK was deemed “extremist,” making it dangerous for any of its employees or affiliates to remain in the country. Shaveddinov fled the country just one night before police barged into his apartment with yet another warrant for his arrest.

He moved to Vilnius, where Volkov, one of FBK’s senior members, had already been based for some time. Over the next few months, Shaveddinov and his colleagues helped FBK’s remaining employees evacuate Russia. The many offices they had opened across Russia’s regions meant that Shaveddinov now had to help hundreds current and former staff find safe passage abroad.

When he arrived, Shaveddinov never anticipated the city would one year later become a hub for hundreds of opposition activists fleeing a country waging a full-scale war against neighboring Ukraine.

Vilnius–the capital of Russia’s exiled opposition

Among the freshly painted Renaissance and Baroque buildings of Vilnius’s Old Town, the Russian language can be heard on almost every corner. Often, it is difficult to distinguish whether those speaking it are Belarusians who arrived after mass protests in 2020, Russian-speaking Ukrainians, recently arrived Russian exiles or even Russian-speaking Lithuanians.

One evening, while getting drinks at a bar with Russian journalists in the eccentric Uzupis neighborhood—once playfully proclaimed an “independent republic” by local artists after the Soviet collapse—I encountered a group of young, Russian-speaking Ukrainian emigres.

My Russian acquaintances bashfully admitted that they had fled the country of the aggressor, but, to their surprise, the Ukrainians did not bat a critical eye. Lively conversation unfolded as everyone understood they were all fleeing the same evil. At the center of it, a Russian-speaking Lithuanian bartender was pouring drinks.

In addition to Navalny’s organization, the Lithuanian capital hosts hundreds of Russian opposition organizations—from LGBTQ advocacy groups to activist artists like members of Pussy Riot, to regional political organizers and independent media outlets.

Some 16,193 Russian citizens currently live in in the country, according to a recent Lithuanian government report. Vytis Jurkonis, a lecturer at Vilnius University who is a leading expert on Russian exile communities, says 10 percent arrived recently on humanitarian grounds.

The newcomers are typically Russian nationals who can prove they would face political persecution at home. Exiled Russian human rights defenders already based in Lithuania assist the government in vetting and, in some cases, red-flagging visa applicants. Unlike other hubs for Russia’s post-war emigration such as Georgia and Armenia, where visa-free regimes have brought in tens of thousands of Russians, the recent emigre community in Lithuania is much smaller and specified, comprised almost exclusively of independent journalists, civil society workers and activists.

Since the start of the war, they have arrived in various ways. One activist who asked to not be named told me how she illegally crossed a land border on foot from Belarus in early March 2022, just a week after Russia invaded Ukraine. Lacking an EU-wide Schengen visa, the 21-year-old activist passed through Belarus because it was the only country that both allows Russians visa-free entry and borders the European Union.

She spoke of a harrowing night crawling under border fences on an icy forest floor with a companion before Lithuanian border guards eventually found her. Facing flashlights and armed men she yelled: “I am a refugee from Russia!”

They welcomed her warmly, fed her and placed her in a camp alongside Ukrainian refugees for a few weeks before she was granted permission to leave.

In hindsight, she says, she could have waited and applied for a visa. But shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine, rumors swirled that the borders would be closed, so many left abruptly in panic.

“I knew nothing really of the country I was entering. I couldn’t even distinguish among the Baltic countries,” she told me.

According to Jurkonis, Lithuania’s geographical proximity to Russia, coupled with the government’s willingness to offer shelter to activists fighting authoritarianism, made it attractive to Russian exiles.

Once they arrive, typically on humanitarian visas, they can apply for residency permits that enable them to stay in the country a year and travel to other countries in the 27-country Schengen zone. They then have the option of applying to extend their permits for another three years.

“[Taking in political exiles] isn’t a new phenomenon for Lithuania,” Jurkonis told me.

“We’ve been accepting Russian political emigres since the 2011-12 Bolotnaya protests,” he explained, referring to major protests that broke out in Russia after dubious national legislative elections and Putin’s decision to return to the Kremlin for a third term as president. “Then in 2020, we accepted Belarusian political emigres en masse [following Belarusian strongman leader Alyaksandr Lukashenko’s brutal crackdown on protests against election falsification]. Since 2021, we’ve begun accepting Russian political exiles again.”

When I asked Jurkonis why Lithuania, a country that was occupied by the Soviet Union for decades and continues to face threats from the Russian government, has taken on the responsibility of harboring so many Russian exiles, he shared with me a more positive take on the history of the two countries.

“Lithuania has a legacy of helping [Russian] dissidents,” he said. The Lithuanian Symbolist poet Jurgis Baltrušaitis, who was also the country’s ambassador to the Soviet Union from 1920 until 1939, played a role in helping Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva and Belarusian painter Marc Chagall flee the Bolshevik regime into Europe.”

“Once they arrive, “ he added, “we hope to give them the breathing room and space to continue the work they could no longer do freely back home.”

Responding to criticism

As if feeling the need to justify his own departure from Russia—especially in the light of Navalny’s own martyr-like return—Shaveddinov repeatedly emphasized that he can do much more abroad than he could back home.

Critics sometimes lambast the exiled Russian opposition for not “staying and fighting the regime.” But Navalny’s imprisonment is a clear indication of what would have happened had they remained.

FBK’s immense popularity has made them targets for other criticism. Some argue that the its perceived fixation on corruption investigations does little to aid Ukraine on the battlefield. Against the backdrop of the war, the logic goes, videos jauntily mocking the Russian elites for their garish tastes seem pointless.

As a major opposition movement with millions of online followers, FBK positions itself as the only reliable alternative to Putin’s regime. But many of its critics from Russia, especially those from the country’s regions, say the organization is disconnected from most of the country’s inhabitants.

Oleg Grigorenko, an exiled journalist from Russia’s northern Komi Republic who now also resides in Vilnius, voiced that sentiment over a coffee. He is the chief editor of 7×7 Horizontal Russia, an independent Russian media outlet that covers how people live in the country’s poorest areas.

“Both [Navalny] and Russia’s political elite have little understanding of how people live in the regions,” he said. “They [FBK activists] spend their time talking about how Putin owns some extravagant palace—but what tangible effect could this have on our lives? Navalny does not have our interests in mind.”

Exiled anticolonialist activists from Russia’s ethnic republics have also taken issue with the organization’s alleged dismissal of the concerns and aspirations of minorities. In February, the leading FBK politician Vladimir Milov was spotted clashing with activists from the organization Asians of Russia at a talk in Berlin.

Prior to the event, Milov had deleted a comment on a video he shared in which a Chechen activist wrote: “A privileged white person tells indigenous peoples how to live.” At the talk, the activists confronted Milov over the ethics of blocking a post they believe raised important issues. Milov responded by saying such issues are “irrelevant” to him.

When I asked Shaveddinov whether he believes the organization is failing to respond to such critiques, he reiterated that FBK’s “singular main mission”—to accelerate the collapse of Putin’s regime—is in the best interest of all Russians.

“We don’t have a single formula,” he said. “We are just working to hit this regime with everything we can––sanctions, corruption investigations and counter-propaganda work.”

But FBK’s loudest controversy was connected with sanctions—the very policy in which it specializes. In March, the organization suffered one of its most significant reputational blows when it was revealed that its most senior member, Volkov, signed off on a letter to European officials asking for the head management of a major Russian bank, Alfa, to be taken off the sanctions list.

Volkov quickly issued a public apology, claiming he had made the decision independently of the organization––a claim Shaveddinov repeated.

“It was a major political mistake on Volkov’s part,” he told me, perhaps sticking to the party line. “But he publicly apologized and addressed the issue transparently—which is something that never happens in Russian politics.”

He said little to further elucidate the motivations behind Volkov’s actions.

In response to the accusations that FBK does little on the anti-war front, Shaveddinov referenced a YouTube channel he had helped launch immediately after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, called Popular Politics, with more than two million subscribers. Using “yellow press” headlines to attract a broad, Russian-speaking audience, the channel invites political experts to discuss what is happening in Russia and Ukraine.

According to Shaveddinov, the channel accumulates 15 million unique views monthly, 84 percent of which are from inside Russia.

“We deliver to these audiences very clear anti-war positions, and we feature Ukrainian speakers, as well as military experts who explain what is happening on the front,” he said. “We show them the full extent of the catastrophe Vladimir Putin has dragged our people into.”

As for the anti-corruption investigations, Shaveddinov justifies the practice by explaining the investigations target two separate audiences. The first comprises Russians who remain in the country and typically stay out of politics.

“Experience has shown that if we explain to our audiences why they live in a world with immensely low wages and shambolic roads, they suddenly become interested in politics,” he said.

“[Russians] will eventually tire of the war, and begin to feel dissatisfied,” he added. “Our goal is to exacerbate this dissatisfaction so that when a window of opportunity presents itself, we can deliver a final blow by galvanizing the public to go out and protest.”

The second audience is the European governments FBK is tirelessly urging to impose harsher sanctions.

To the group’s disappointment, they have been slow to ramp up pressure.

“Europe talks the talk that it’s imperative to fight dirty money and that mass sanctions are also imperative,” Shaveddinov said. “But when EU countries spend months discussing [whether or not] some 15, 30, 40 Russian oligarchs or corrupt officials deserve to be on these lists, this affects nothing.”

“We need mass sanctions, including against their family members, because they receive benefits from all of this [corruption and war],” he added. “Obviously some random Russian general or official won’t travel to Europe out of concern for their own safety—but their wives and children continue to fly to Europe monthly to spend their blood money.”

He points to an example in the Czech Republic, where the family of Boris Obnosov, a Russian businessman who runs his country’s largest missile-production company, continues to reside unhindered. Last month, Czech President Petr Pavel made a controversial assertion that all Russians living abroad need to be closely monitored, saying that was “the cost of war.”

Navalny’s team then raised questions about why the Czech government continues to allow relatives of Russian warmongers to own real estate in their country. Pavel responded by saying the country lacks the mechanisms to effectively freeze such assets, a problem Shavedinnov said could be quickly rectified.

“They approved their own Magnitsky Act,” he said, referencing a law passed in 2022 that enables the country to sanction “foreign entities violating human rights or supporting terrorism.”

However, the current rules do not extend to the relatives of such “entities,” making it difficult for the government to impose sanctions against Obnosov’s family.

Such bureaucratic inertia regarding sanctions predated the full-scale invasion, Shaveddinov noted.

“Europe made a catastrophic error in 2014 when it failed to impose targeted sanctions in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea,” he said, recounting how he and Navalny wrote letters to European officials explaining that leaving Putin unpunished would encourage him to be even more aggressive.

“That is why he decided to invade Ukraine,” Shaveddinov said. “He thought he would take the country in just three days, and Europe would close its eyes once again. Now we see how some Western companies, even after 2022, continue to earn money through their Russian partners—this is strange and hypocritical.”

When I asked what impact FBK expects from such sanctions considering that Russian elites still control vast wealth back home, he argued that targeting close relatives of Kremlin enablers would create tensions within their households and, by extension, within the ruling apparatus.

“If all the wives and children of Russian elites fall under sanctions, those wives and children will come and say: ‘Why can’t we spend time in the West anymore?’” he explained. “That would create schisms and irritation within the families of the elites, who would then put pressure on Putin.”

Personal safety

Even abroad, Shaveddinov clearly wears a target on his back.

In 2022, the Russian government charged him in absentia for purportedly “discrediting the Russian armed forces,” adding a criminal case to his “foreign agent” and “extremist” designations.

When I asked if he fears for his life in a country which, due to its proximity to Russia, could very well be swarming with Kremlin agents, he responded seriously.

“It’s obviously a matter of grave importance. Before, the siloviki had their hands full targeting journalists and opposition activists,” he said, using the colloquial Russian term for police and security agents. “Now that they’ve squeezed us out of the country, they still need to continue their work somehow.”

“Even with the NATO summit taking place a few kilometers away, we were still in danger because the Kremlin has no limits,” he added. Numerous Kremlin opponents have been attacked and even killed abroad for years. Former Federal Security Service officer Aleksandr Litvinenko, for instance, was assassinated in London in 2006 by Russian agents who slipped deadly poison into his tea.

As a result, Shaveddinov takes “banal precautions” like looking around every venue he enters and not drinking from random teacups.

“[Navalny] often told me that if you constantly think about being watched, you will go insane from paranoia. So just keep doing your work and minding your business,” he said. “At the end of the day, if you’re an ordinary individual who is fighting against a government that has all the poisons and other tools to take you out at any moment, even 10 bodyguards can’t save you.”

Navalny is held in a “special regime” prison, part of a system that succeeded the notorious Soviet Gulag. The charismatic opposition leader will spend the foreseeable future under the country’s toughest prison conditions alongside murderers.

Even the well-known pro-Kremlin political scientist Sergei Markov questioned the decision, calling it a “horror.” However, he also claimed that Putin was “probably” not aware of—and may even have been repulsed by––the harsh sentence, which he alleges was imposed by an “overzealous bureaucracy.”

Shaveddinov refutes the claim.

“We had no illusions,” he said. “We knew that this decision was being made at the highest level of government—and the number [of years] doesn’t mean a thing.”

FBK charged that Russia’s security services had pressured the court to impose the harsh sentence.

“We all know this will only end with the fall of the Putin regime,” he concluded. “But we will not give in to depression. We are now fueled by even more rage and will do everything in our power to put an end to this regime.”

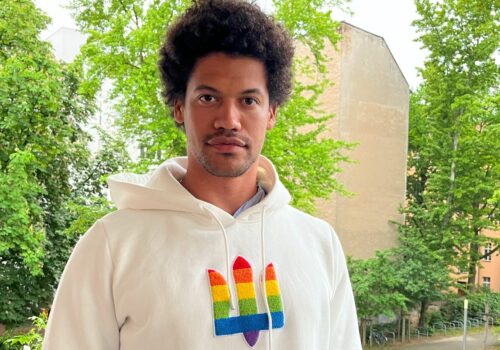

Top photo: An FBK activist in front of the recreation of Navalny’s prison cell