LISBON — Paul’s accent cut like a stiff morning breeze across Boston Common: “This program saves lives,” he said forcefully. He sipped coffee from a cardboard cup and tucked in his winter coat tighter around his neck. For a second, I thought I might be back in that puritan city as I waited for my ham and cheese croissant toasting under the middle-aged barista’s watchful gaze.

The staff of the methadone van I was shadowing that morning talked among themselves, happy for a reprieve. “And not just their breath but what makes life worth living,” Paul added about recipients of the team’s aid. “They got their friends back, their kids back, their life back. Some people still use but that’s okay.” The methadone program had saved Paul’s life, now he was waiting to get his daily medication.

Once the equipment was set up and he got his dose, he explained that he had grown up in New Bedford, Massachusetts. Caught trafficking a kilo of cocaine in the 1990s, he’d spent several years in prison before the government deported him to Portugal, where his family was from. Thanks to the methadone van program’s open-door policy, Paul joined in the early 2000s. He greeted the staff and others who came for their medication with the same mix of friendliness and brusqueness that comes from seeing the same people every day for years.

As Paul went off to chat with an acquaintance, I took in my surroundings. In the Netherlands and Portugal, low-threshold medication-assisted treatment (MAT) has been crucial for bringing their opioid crises under control. Under the treatment, people with opioid use disorder (OUD) are prescribed some form of opioid antagonist treatment (OAT) such as methadone or buprenorphine.

The medications quench the body’s desire for opioids and allow people with OUD to go about their day without fear of physical withdrawal, which is otherwise debilitating. The program’s low-threshold nature means anyone who tests positive for opioids can begin treatment that day and continue using drugs while receiving methadone. The service is provided free of charge. Other programs I’ve encountered successfully allow patients to receive week- or month-long take-home doses, so they don’t need to come in every day. That frees them to hold steady jobs, visit family and otherwise live regular lives.

As I conclude seven months living in Portugal, after six months in the Netherlands, it’s hard not to leave impressed by the effectiveness of the Portuguese model. It pulled the country out of a catastrophic heroin crisis by following evidence-based practices and treating people with dignity. As in the Netherlands, Portugal’s public health approach has also improved the lives of everyone in a society in which everyone can now walk safely in the streets. It also became clear from my first month that international proponents and opponents alike misunderstand the full breadth and intricacies of the model’s architecture.

As I wrote in my December dispatch, at the height of the country’s heroin crisis in the 1990s, approximately 1 percent of the population used heroin—more than the proportion using opioids in the United States today. At the time, 80 percent of people who injected drugs were positive for Hepatitis C and 60 percent for HIV. Approximately 350 people would die from fatal overdoses every year. In Casal Ventoso, a notorious Lisbon neighborhood that for a time was Europe’s largest open-air drug market, tuberculosis rose as high as 14 percent. An astounding 2.5 percent of Portuguese teenagers aged 16-18 admitted to using heroin. To top it off, 90 percent of people using heroin had never accessed treatment.

Thanks to well-rounded national drug strategy reforms in 1999 that addressed treatment, harm reduction, social reintegration and decriminalization, the number of people using heroin dropped from 1 percent of the population to 0.3 percent within a decade. Overdoses dropped by almost a fifth, from 350 a year to 74. Cases of new HIV infections in people who used drugs went from 1,798 in 1999 to 17 in 2021.

Moreover, Portugal’s drug-use rates have consistently remained under the European Union average along with the number of drug-related deaths. Of the country’s prison population, only 15 percent is serving time for drug-related crimes compared to around 43 percent in the US federal prison system. Portugal also ranks 7th–safest country in the world on the Global Peace Index while the United States ranks 132nd.

Nevertheless, as I toured the country’s drug-treatment architecture—methadone vans, outpatient and inpatient treatment centers, and therapeutic communities—it was hard not to miss cracks fraying the once-robust system.

I followed Lisbon’s two methadone vans for two days, one covering the city’s east side and the other the west, to observe how the programs operate and what other countries might learn from them. Medication-assisted treatment has proven to be incredibly effective for improving health and life outcomes for patients. Yet fewer than one in five Americans with opioid-use disorder are treated using the method, mainly due to stigma and high-barriers to access mandated by federal and state governments. In Portugal, the number receiving treatment is one in two.

The crowd at the first west-side stop the morning I met Paul was the most active. The methadone van and support van that accompanied it set up near a busy throughway used by commuters into and out of the city. It’s also next to the Casal Ventoso neighborhood and a few minutes’ walk from one of Lisbon’s drug consumption rooms. Patients arrived to get their medication by car, motorcycle, scooter, bike and on foot. The morning was still young; many arrived in branded professional vehicles or otherwise clearly on their way to work. Their pitstops would impress Formula One drivers.

Each van route has one stop next to a busy commuter lane and another closer to social housing blocks where the use of heroin is particularly high. The goal is to make access to treatment easier than accessing heroin.

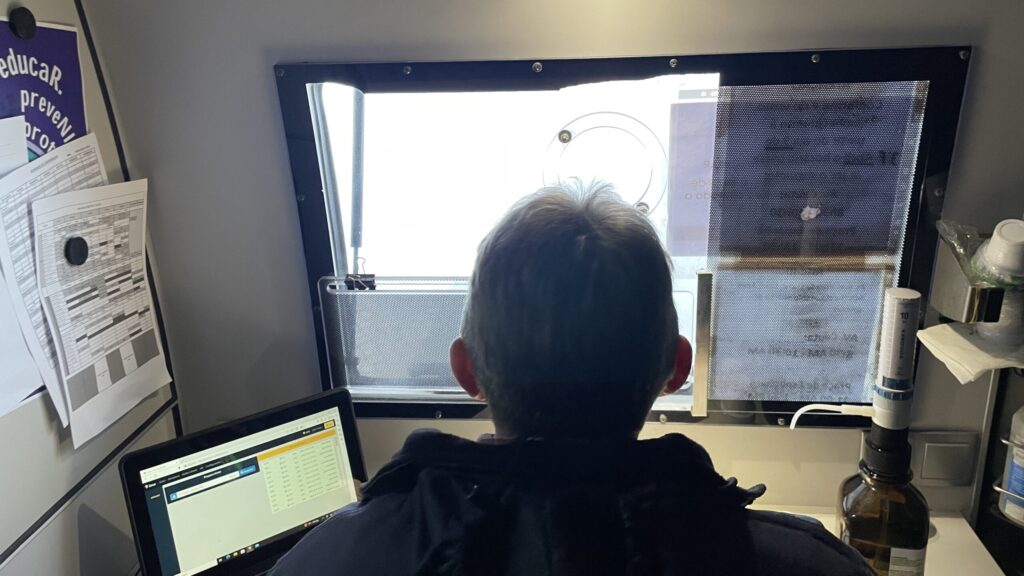

Inside the van, a nurse dispenses methadone doses from a transparent container with practiced repetition: 30mg, 80mg, 50mg. The clear liquid fills small plastic cups which grateful-looking recipients on the other side of the window, primarily men, take with water from a faucet protruding from the van’s side.

One man walks up to the window and gives his identifying number. A notification pops on a screen and the nurse hands him a prepared cup with additional psychiatric medication. The next time an alert comes up, the nurse tells the man he is due for a medical check-up and points him toward the second van. He calls over one of the team’s educators to help convince the skeptical patient.

“The methadone program is not just about methadone,” Carolina Marquez, the program coordinator explains. “It also creates an access point to provide holistic care and referral services for people who use drugs that are otherwise on the margins of the health care system.”

Running on approximately 900,000 euros a year from the government, Carolina and her team serve 1,200 people per day across both van routes with about 1,700 total clients registered in the program. The number has remained stable over the past 10 years, demonstrating that once people join, they tend to stay. The program runs with the help of 10 nurses (one per van per shift), six full-time and four part-time educators who help engage patients, and 10 case managers. One general practitioner doctor joins each van once a week, and a psychiatrist serves as clinical director.

However, the program is under strain. There has been no increase in funding since the 2008 financial crisis. Meanwhile, inflation has raised prices by 28 percent. That has forced staff and material shortfalls. Carolina complains that she currently has money for only 10 case managers when she should have 15, forcing each to support 120 clients. The resource squeeze means it’s also difficult to retain staff, attract new people and train everyone properly. The limited staffing and high turnover rates have also reduced the quality of care.

The month before my visit, the program was forced to cut its hours in half, from all-day operations to only offering methadone services in the mornings. That has already caused a loss of patients. When I spoke about the situation to the director of Portugal’s National Unit for Fighting Drug Trafficking, Artur Vaz, he was immediately concerned. “These cuts will mean more people buying heroin from the street, increasing demand for illicit drugs and with it drug trafficking activity and profits in the country,” he said. It’s Newton’s third law: For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

Carolina says the average age of patients using the program is 48 years old. They are 86 male and up to 25 percent homeless. Some 80 percent are Portuguese, and 17 percent are immigrants from India, Nepal and other South Asian countries. The immigrant cohort trends younger, and her team is finding ways to navigate the language and cultural barriers the new patient population presents.

As mentioned earlier, the methadone vans do much more than just treat the symptoms of OUD. Of those who use the service, 15 percent are HIV positive, 55 percent have hepatitis C (13.5 percent have both) and 1 percent have tuberculosis. By providing additional medical attention, the program cares for 20 percent of people who live with HIV in Lisbon, an astounding 50 percent of those with Hepatitis C, and 100 percent of those with tuberculosis. The program demonstrates the power of low cost, low-threshold mobile treatment. Cuts to the services are devastating for individual and public health well beyond substance use disorder.

When I asked Carolina what she would do if her funding had kept pace with inflation, she thought immediately about her overstretched staff: hire more people, train everyone with continuing education and ensure better working conditions—all of which, she notes, leads to better care for patients. She would also use the extra money to try new creative approaches to engage patients. The program produces a lot of data that her team doesn’t have time to properly process beyond general basic trends.

My two days shadowing the methadone vans left me hopeful about how such a program could transform care in the United States. Paul said it best: “This program saves lives.”

Still, I was concerned about the flatlined budgets and reduced operations. Perhaps the other legs of Portugal’s treatment stool would offer more hope. However, my arrival a few weeks later at Lisbon’s premier public treatment clinic only heightened my apprehension.

Toward the back of the Taipas general hospital complex, past unworried security guards who waved me through, the director, a doctor named Miguel Vasconcelos, gives me a hearty welcome. In typical Portuguese fashion, our scheduled hour-long meeting turns into a two-and-a-half-hour tour.

Vasconcelos is part of a generation of medical professionals who joined the burgeoning field of addiction medicine at the height of Portugal’s heroin crisis in the 1980s and 1990s, when death and estrangement tore through families and communities, filling the streets with vagrants from all socio-economic classes. A scene Americans are intimately familiar with today.

The government opened the clinic in 1987 with great fanfare, dedicating it to treating people with heroin addiction. The center was immediately overwhelmed and satellite clinics were swiftly set up in most of Portugal’s regional states. At its height, Taipas employed 150 staff members. Today it juggles 50. A photo in a staff cubicle, faded by time, shows a festive Christmas party from a bygone era.

The patient population, too, has shrunk over the years and while some still come here for opioid related care, growing numbers struggle with crack cocaine, a rising problem in the country. Taipas offers out-patient treatment such as methadone and mental health consultations as well as residential rehabilitation. Patients receive comprehensive outpatient treatment from a team consisting of a psychiatrist, a psychologist and a social worker. The multi-disciplinary group uses evidence-based methodologies to address patients’ mental health and social wellbeing within society at large.

Vasconcelos shows me around the methadone dispensary, therapy consultation rooms, physical therapy gym and occupation rooms where non-medical programing such as arts and crafts takes place. It is difficult not to notice the peeling paint, decades-old furniture and outdated equipment. “We started a technology workshop for patients but ended it early because their phones were more modern than our computers,” he says ruefully.

We finish our tour at the residential rehabilitation quarter on the third floor of the main building. The unit’s chief was retiring in a few months. “It will be hard to find a replacement,” Vasconcelos adds with a sigh.

“Why,” I ask?

He gives me a sunken look. “When I arrived at Taipas as a young doctor in 1992, working here was prestigious and well-paid. You had to be top of your class! Now that the heroin crisis is a distant memory, people have forgotten about importance of caring for those who use drugs, and new doctors can get paid more than double at the private hospitals.”

Taipas’s funding has been stretched and kept just above water level. As director of Portugal’s most distinguished addiction treatment facility with over three decades of experience, Director Vasconcelos is paid a paltry 2,500 euros a month, meaning he must buttress his salary with private consultations on the side. He’s stayed on so long because he never lost the spark that drives him to help those suffering and struggling with substance use disorder. As the youngest of the old guard with his own retirement soon approaching, he frets about what will happen to his beloved center and patients.

Well beyond the walls of Taipas, Portugal faces a critical shortage of qualified doctors and medical professionals decades in the making. In addition to stagnating funding across the country’s national health service, Vasconcelos believes that education policies limiting the number of medical students is coming back to haunt the country. To top it off, 30 percent of young Portuguese have moved abroad to chase better work opportunities, heightening the national labor shortage. The struggles seen at Taipas, the methadone vans and across the drug treatment architecture, therefore, reflect the symptoms of larger structural problems plaguing Portugal’s public health care system.

Arriving at the therapeutic community run by Ares de Pinhal, a non-profit service organization that also runs Lisbon’s largest drug consumption room, can be bewildering the first time. Half an hour from the city center, my taxi leaves the highway to weave through small streets where trees and fields slowly outgrow concrete structures. The driver stops the car at the beginning of a dirt road signaling the end of where he’s willing to take me. Luckily, the house and grounds are only a short walk away.

The property stands on an acre of land in an orange grove full of fresh fruit. Up the driveway at the main house, Rodrigo Coutinho, the head psychiatrist, and his team meet me along with a visiting delegation from Tunisia.

The building holds a shared dining room, kitchen, TV room, staff offices and dorm rooms. As we walk up the left side of the house, we pass a laundry room, woodworking shop and semi-outdoor living space all run by patients. Residents here are in the second and third phases of treatment, meaning they’re learning to build trusting relationships, take responsibility for tasks, manage conflicts though communication and organize their time. Those nearing the end of the program work real jobs outside the compound but still sleep at the residence, ensuring a smoother transition back into society. At the top of the hill is a pool with a nice view of the of the surrounding small valley. Not a bad spot, I think to myself.

Therapeutic communities are best suited for the small percentage of people who are unable to organize their personal and professional lives with outpatient care alone. To receive a license as a health care provider and be reimbursed by the government for its services, the programs must obey the country’s 1997 regulations requiring multi-disciplinary teams and evidence-based practices.

Under those regulatory conditions and when participants take part voluntarily, therapeutic communities provide the structure necessary to foster abstinence in people along with distance and time away from the life circumstances that had been fueling problematic substance use. Many communities accept MAT while some do not.

The programs are a far cry from the non-evidence based and lightly regulated month-long anecdotal horse-petting vacations or military-style boot camps that call themselves rehabs in the United States. To complete the thorough program of a therapeutic community, patients here stay between one-and-a-half and two years, going through three distinct stages.

In the first reception phase, which lasts several months, the staff’s goal is to make individuals feel welcome by building trust while slowly introducing rules and routines. Substance use is not allowed from day one although a re-occurrence of use does not necessarily precipitate expulsion.

During the second and third phases, patients are often moved to separate facilities to avoid negative influences from those recently joining, who may still be secretly using. In the second phase, the focus is on intensive group and individual counseling to address the root causes of addiction and develop social and professional skills. Residents can remain in this phase for over a year.

In the third phase, the staff supports people in their transitions back into society, which can take up to six months. During this period, they are connected with another pillar of Portugal’s drug strategy: socio-professional re-integration. Portugal’s decriminalization of all drugs plays a strong role by reducing the barriers to re-entering society that people with criminal records otherwise face. At the onset of the reforms in the 2000s, re-integration programs included tax breaks and government-paid wages for small businesses that hired those in recovery. Although the incentives were very effective, budget cuts have ended them, and re-integration services now look more like traditional employment assistance.

There are around 50 therapeutic communities across Portugal with a shared capacity of 1,300 to 1,400 beds. Three are run by the government while the vast majority are managed by non-profits. Care ranges from luxury villas for families willing to pay extra, to religiously oriented programs, to simpler facilities that can be just as effective. Ares de Pinhal falls on the more modest end of the spectrum.

Coutinho comes here twice a week to hear from staff about residents’ trials and successes, and to share advice. Many residents are co-diagnosed with other psychiatric disorders that need to be managed in addition to substance use disorder. Coutinho is also part of the old guard and has officially retired but continues to help a few times a week because it’s unclear if he can be replaced. As he drives me back to Lisbon, he, too, complains about reduced funding and struggles keeping and hiring staff.

To the question of why funding for substance use services has declined, his answer is curt: “political will.” When the government pushed through its historic reforms between 1999 and 2001, the heroin crisis was the number one issue for voters. It now languishes around 14th place.

If drug policy is mentioned by politicians today, it’s most likely by the far-right party Chega, which in the past six years has gone from having a single legislative representative to being the second-most powerful party in the country as of last May. In familiar rhetoric that echoes from across the Atlantic, its leaders scapegoat immigrants for increases in homeless and street drug use, both of which experts say are primarily due to skyrocketing housing prices that have more than doubled in the past decade while wages have increased by only a third.

João Goulão does his best to sound optimistic. The doctor heads the recently reconstituted Instituto para os Comportamentos Aditivos e as Dependencias (ICAD) under the Health Ministry, which now coordinates drug policy at the national level. While successive political crises have led to stagnated funding, he believes the country’s recently re-elected center-right coalition is open to funding increases that will reinforce existing health and social responses. His nightmare scenario would be a return to the pre-2000 status quo of harsh repressive policies currently proposed by the far right, which had only worsened the heroin crisis throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

It must be repeated that the Portuguese model has been incredibly effective in solving the country’s heroin crisis and continues to serve well by offering a wide spectrum of services available to people where they live and work.

But one accurate criticism of the model is its relative inflexibility. The system and procedures don’t seem to have changed much in the past 25 years. That could be an Achilles heel as it faces three forces testing its structural integrity: lack of political will that has already cut budgets by 30 percent compared to 15 years ago, a country-wide shortage of health care professionals and affordable housing as well as a new mixture of drugs in the illicit market.

The last threat is the most unpredictable. While the vast majority of Portuguese who use drugs smoke cannabis, the country’s heroin supply is at risk of being contaminated with fentanyl, people of all ages are increasing experimenting with new synthetic drugs and there is an alarming rise of crack cocaine use. Unlike opioid use disorder, which can be effectively managed with MAT, crack cocaine and the new drugs do not yet have similarly effective treatment therapies.

Director Vaz of the anti-trafficking unit notes that while most cocaine enters Europe through other countries, drug traffickers are increasingly using Portugal as an entry point to the rest of Europe. In 2024, Portuguese police seized over 23 tons of cocaine, more than double the amount seized in 2020. While it remains primarily a transit country, the large increases mean more cocaine is making its way to the street market, reducing prices and increasing access.

The Portuguese found something that worked very well and have stayed with the same playbook for 25 years. They are now straining to hold up the high standard quality of care they’ve become known for while forces outside their control slowly chip away at the system around them. Time will tell if they will be able to adapt their model to face the new threats.

As I bid my Portuguese hosts farewell, I can’t but admire the lifelong commitment to service that Carolina, Miguel, Rodrigo, João and the countless others I met throughout my time here have made in caring effectively for those who use drugs while promoting dignity and health. In so doing, they demonstrate a different path forward, away from the global status quo of repression, ostracization and criminalization.

Top photo: Methadone van