TBILISI — A tony crowd of middle-aged Russian expats crowded the ash wood floors of a gallery here one April evening for a recital by the émigré pianist Polina Osetinskaya, who had performed at Carnegie Hall months before. Amid the gowns and tuxedos, a torn cream-colored sweater hung on a lanky actor eagerly waiting to take the stage next for his own act.

But after Osetinskaya concluded her recital on a white grand piano, the event organizer—a Russian businessman and socialite who hosts events in the Georgian-owned I-Art Gallery—reluctantly asked members of the crowd whether they would like to see one more act or were content with “having an extra 15 minutes to mingle.”

A small chorus of female fans cheered for the eager actor to take the stage.

“May I introduce a decorated young actor who graduated from the Moscow Art Theater?” the organizer said dryly, referencing the world-renowned venue to lend the young man some credibility.

Clearing his throat, the 28-year-old actor—who asked to be called by his nickname Lenik, picked up during his year as a high school exchange student in California—began reciting a poem by the late Soviet poet Boris Rizhy. Following a mixed reaction from the audience, he grabbed an acoustic guitar to belt out Bob Dylan’s “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright” in a thick, twangy Russian accent.

Some held fingers to their chins, as if contemplating the performance for deeper meaning. Others laughed, accepting the gig for what it was—simple entertainment, as Lenik would call it. With his head of unkempt hair, jumpy eyebrows and catlike intonations, he was a strange but apparently entrancing phenomenon for many attendees.

For several months after he fled Russia’s September 2022 “partial mobilization” for the war against Ukraine, he had consistently drawn crowds to his eclectic performances. He hosted comedy shows at Russian expat clubs, fronted a rock band, and, occasionally, recited poetry and contorted his body for older Russian emigres at the I-Art Gallery. His shows brought in a steady income.

But as the summer of 2023 rolled around and Tbilisi’s émigré community of some 80,000 shrank—some continued further on to Western Europe while others returned to Russia—so did Lenik’s audiences. While statistics are hard to determine because official Georgian numbers do not distinguish between Russians who enter as tourists and indefinite expats, one report from the Interior Ministry published this October states that roughly 14,000 Russians have left the country since the start of 2023.

When I called Lenik before boarding a flight from Riga to Tbilisi in July, I was taken aback to hear he had decided to return to Moscow.

The reason, he said, was that he could no longer afford rent in Tbilisi. He had tried turning to Georgian directors, but they rebuffed him from fear of a public backlash over casting a Russian. Back home, with the danger of another mobilization apparently diminishing, Lenik hoped to return to earn some money before planning more concrete steps to emigrate again.

Facing language barriers, navigating a highly politicized climate and struggling to cater to new audiences, many young actors like Lenik—some with impressive resumes and diplomas from Russia’s world-class theater institutions—have been struggling to find work abroad. Even in London, which feels far further from the war than Tbilisi and has historically welcomed Russian culture, some high-profile movie actors have been told by agents that producers are hesitant to invite them to castings as long as Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine continues, fearing reputational blunders. Also like Lenik, many are returning to Russia even if some perceive their decisions to be a small victory for the authoritarian President Vladimir Putin.

The court jester

Not all Russian émigrés face that kind of wrenching choice. At the I-Art Gallery event where Lenik performed, many in the audience were in the privileged position of being able to continue living between Moscow and Tbilisi.

Their politics were unclear. In conversation, they bemoaned the “cancellation” of Russian culture. Not once was the war against Ukraine mentioned. With its rich dinner spread and lavishly dressed attendees, the gathering felt like an alternate reality after the typical, bare-bones cultural events hosted by younger Russian exiles at which donations are gathered for Ukraine.

That mattered little to Lenik.

“They call me the court jester here, but tell me, how can I be a jester for a court of jesters?” he told me after his performance, adding that a regular at such events had admitted to “weeping from grief” when he heard in April 2022 that Ukrainian missiles had sunk the Moskva, Russia’s flagship Black Sea missile cruiser.

Lenik would often lambaste his fellow thespians in Tbilisi for “sitting on their asses, thinking about how to best utilize their craft” to make moral or ideological points while he kept busy entertaining any way he could think of. He justified his politics-free performances by saying they were his “honest” way of bringing people joy in dark times. Attempts by fellow actors in emigration to reflect on their status as exiles or on the war felt contrived to him.

But unlike the many graphic designers, programmers and journalists who fled Russia and have largely found professional opportunities abroad, actors have found it tough going. And Russia’s still-open borders have made the prospect of returning viable for those who have failed to gain a foothold. Many, like Lenik, have returned over the past year, typifying a wider trend of post-invasion emigrants prioritizing financial stability over moral or political convictions.

But while they can still make money acting in television commercials back home, the Kremlin’s takeover of the country’s theaters has left opportunities open only to those willing to publicly endorse the war. Actors in Russia have been forced to make significant compromises to continue their careers.

The new censorship

Perhaps Russia’s most esteemed cultural institution, the theater was one of the first arenas to be targeted by new political censorship in the days following Russia’s invasion. Despite Putin’s attacks on media and civil society over the last quarter century, many of Moscow’s theaters had previously remained spaces for creative freedom. But the invasion of Ukraine changed everything. Many independent journalists have chronicled how the government transformed theaters into another part of its propaganda machine.

It began with the cancellation of plays directed by or starring those who had either fled or publicly opposed the war. Soon, their names would entirely disappear from theater playbills and websites. Chulpan Khamatova, for example, a Russian star actress who had signed an open letter opposing the invasion shortly after it was launched and later fled to Latvia, disappeared from the website of Moscow’s Sovremennik Theater. Some had previously accused her of siding with the Kremlin during earlier crackdowns.

Moscow’s Meyerhold Center, once a bastion of experimentation and progressive thought, saw its former directors replaced by Kremlin loyalists. The Gogol Center, founded by the now-exiled dissident director Kirill Serebrennikov, was hollowed out and rebranded as a regime-backed institution. The final show at the original venue before it was renamed the Gogol Drama Theater was a play based on the Soviet writer Yury Levitansky’s poem “I Don’t Take Part in War.”

Actors who wished to continue their careers but publicly opposed the invasion during its early stages are now sometimes forced to repent by issuing pro-war videos. One who made an antiwar post on Instagram in March 2022 succumbed to pressure after a year without work, recording a clip asking for donations to a non-profit that helps Russian doctors in eastern Ukraine.

Even the internationally famous actor Aleksei Serabryakov, once a vocal critic of Putin’s regime, recorded a video in July 2023 expressing sympathy for a girl in a Russian-occupied part of eastern Ukraine who was injured in a missile attack. Although he did not explicitly name which side was responsible for maiming the girl, the video was shared by the nationalist musician Nikolai Rostorguyev—sanctioned by the West—who claimed to have urged the actor to record it. Serabryakov’s motivations were unclear, but his haggard expression in the video suggests he may have been under pressure.

In one episode after Russia announced its mobilization last September, the director of a comedy theater in an unnamed Russian city was tasked with recruiting a troupe of actors to entertain soldiers at the front, according to The Financial Times. Those who agreed were reportedly granted immunity from conscription.

Across the country, theaters now also brandish the Latin letter Z, one of the Kremlin’s symbols showing support for the invasion.

Censorship may have descended on Russia’s drama world like an avalanche after February 2022, but the phenomenon had already been noticeable in the pre-invasion period. Many major theaters are partly state funded, giving the government significant leverage over them.

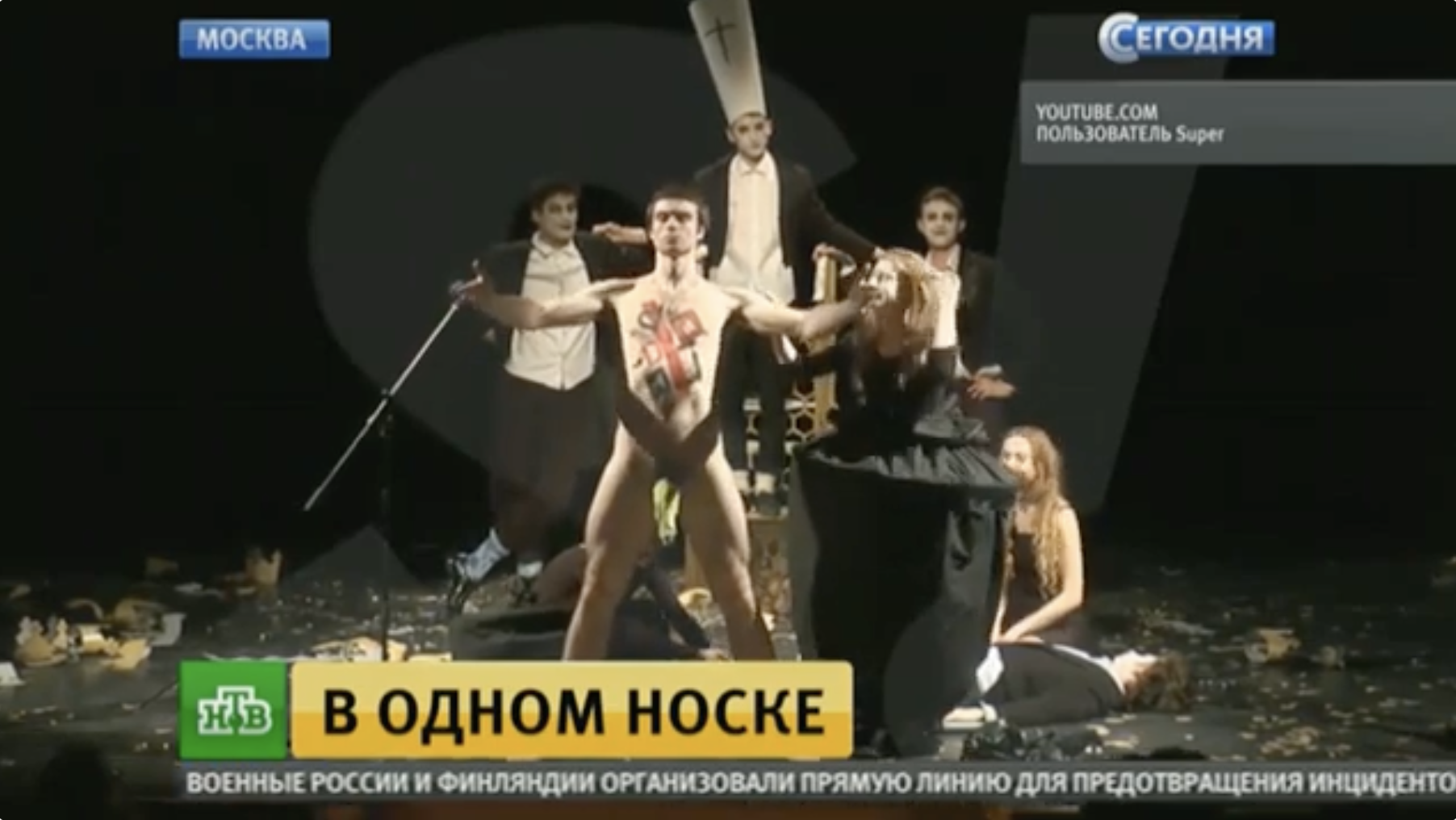

The authorities once reprimanded the participants of a show Lenik produced in Moscow. In 2017, when he was still a student at the Moscow Art Theater’s Dmitry Brusnikin workshop, he starred in a provocative play based on the works of the Soviet avant-garde writer Ilya Zdanevich. It was staged at the Mikhail Shchepkin Higher Theater School in Moscow, known for its conservative artistic traditions.

Lenik tossed buckets of water at the audience before stripping naked to reveal futurist designs painted on his body. It was not well received. A professor at the school chastised the performers in front of the crowd in an interaction that was later aired on state television. Some weeks later, the Culture Ministry phoned the Moscow Art Theater’s directors to demand they punish Lenik.

They refused, an act of defiance demonstrating that certain institutions were still able to resist pressure from the authorities.

That was before the invasion of Ukraine. What the future holds for them is uncertain.

‘Serious, bloody and mad’

In another growing hub for Moscow’s exiled creative community, Berlin, I attended two shows designed to be more than mere entertainment. One examined the cyclical nature of Russian emigration through the works of Aleksandr Galich, an exiled Soviet poet-bard. The other was a reading of the politically charged play Finist, the Brave Falcon, dedicated to its author, Svetlana Petriichuk, and director Yevgenia Berkovich, both of whom were arrested in Russia in May for purportedly “justifying terrorism.”

While both shows drew full houses—the former, primarily Russian audiences and the latter, mixed—they were held in small, fringe spaces. Only world-famous theater directors like Serebrennikov and Dmitry Krymov have successfully produced mainstage shows overseas.

Leave? Leave!—which actor Igor Titov co-authored, directs, stars in and showcases in Berlin—is financed by a Russian patron he chose to not disclose and has now had three runs in Berlin. It is staged in a small industrial art space in the Charlottenburg neighborhood—once home to exiled Russian writers and artists in West Berlin who had fled the Bolshevik coup in 1917—with windows overlooking the Spree River.

In the first act, the Soviet poet Galich scrambles to gather his belongings and say parting words to close friends during his last minutes before exile. He considers taking a book by Osip Mandelstam, the venerated Soviet poet who died in a labor camp. “No, border security would never let me through with it,” he says. The ominous hum of a car—implied to be a KGB escort parked outside—was audible throughout.

At the end of the act, Galich’s conversation with his wife is abruptly interrupted by a blinding light. She clings to him as they stand motionless for a few moments before he slowly wanders off stage into darkness. A radio transmission announcing his death follows.

The Soviet authorities exiled Galich in 1974 for his anti-regime songs and he was found dead by his wife three years later in Paris, clutching a piece of recording equipment plugged into an outlet. Although the circumstances remain a mystery, many suspect he was assassinated by the KGB. The French authorities never released the results of their investigation.

“In this work, we try to show that emigration from the Soviet Union in the 1970s amounted to certain death,” Titov later said of the play. But the director, who had initially fled Russia for Mongolia after mobilization last September, does not characterize his own departure the same way.

“I left my childhood hometown for Moscow [to study at the Moscow Art Theater], with the same ease I left Russia for Berlin,” he told me, sipping a cold brew and sporting a Misfits T-shirt outside a cafe on a tree-lined, cobbled street in the gentrified Prenzlauer Berg neighborhood.

“I’ve always been inspired by émigré theater and am eager to continue the tradition,” he said, mentioning Snow Show, a well-known production by the performance artist and clown Slava Polunin.

While Leave? Leave! attempts to draw historical parallels with current events, it makes no direct reference to the ongoing war in Ukraine. Titov justifies the omission. “War is shame; it shouldn’t become an item [discussed] in the language of the aggressor,” he told me. “Saying ‘no to war’ won’t change a thing.”

Nevertheless, the production serves as an example of how Russian émigré actors can draw audiences by ruminating about current events.

In the second act, the actors return to the stage dressed as Russian and Soviet cultural figures. They pace around the room, muttering excerpts from their characters’ works that reflect the cyclical nature of Russia’s struggle with its own national character and authoritarian disposition.

“Is our tolerance of suffering a sin?” Viktor Astafyev, a Soviet writer who rebelled against socialist realist conventions, asks. “It’s a sin in the sense that it always ends badly in Russia, with such blood…”

“During times of war, the tyrant always gets closer to the people,” mutters Varlam Shalamov, a Soviet dissident writer who is most widely known for his chronicles of Josef Stalin’s labor camps.

“A cruel moment has descended on the streets, a moment when every statement must be signed off with something serious, bloody and mad,” says Yegor Letov, the late poet and former front man of the dissident punk band Grazhdanskaya Oborona (Civil Defense).

For this room full of Russian émigrés—exiled journalists who carry “foreign agent” labels back home, cultural workers and actors—history was repeating itself.

“This is therapeutic for people within our circle,” Titov explained to me of the second act. “[At this moment] it’s not correct to do something entertaining and bombastic—this is a theater on suitcases. We’re like pilgrims.”

The show sought to urge Russian viewers to find a way to break free from this cycle, he added.

“It’s the 21st century,” he said. “There is artificial intelligence and yet we’re still here reflecting on all of these tendencies.”

Although the show had German subtitles, I wondered how all the somber self-reflection could resonate with a foreign audience. Titov responded by pointing out that a noticeable crowd of older Germans attended on opening night.

“This play seemed to resonate with them, especially [older Germans] who grew up in the German Democratic Republic,” he said of communist East Germany, mentioning several motifs in the show that evoked the ever-present surveillance state.

The second production I caught in Berlin confronted current events more explicitly, drawing noticeably larger German audiences. A group of actresses—Russian and German—staged a reading of Finist, the Brave Falcon, a contemporary Russian play that was the pretext for the arrests of Berkovich and Petriichuk in Russia in May.

The reading was directed by Masha Sapizhak, 31, who fled Russia in March 2022 after spending a night in jail for protesting the invasion of Ukraine. A small German grant funded the rental of the space, and most participants worked without pay.

A crowd of roughly 80 people filled a small venue in Berlin’s predominately Turkish Wedding neighborhood and comprised Germans and Russians in roughly equal measure. Taking its name from a Russian fairy tale but based on a true story, the play centers on a Russian girl recruited by Islamic State militants through dating websites. The actresses shift roles—from the girl herself, who obsessively Googles “how to fasten a burka” to the IS fighters and the calculating, bureaucratic Russian judicial machine that eventually convicts her on charges of aiding and abetting terrorists.

The actresses portrayed the lead character as a naïve and trusting young woman who is a victim of coercion by masculine ideological forces. But she remains strong in the end, sticking to her convictions despite her hopeless predicament.

In an ironic and tragic twist of fate, Petriichuk, and Berkovich are now facing seven years in prison for “justifying terrorism.”

Many suspect the real reason was a series of antiwar poems Berkovich had earlier published online. The authorities, the logic goes, retroactively turned to the staging of the play and its portrayal of the main character in a sympathetic light as grounds for the arrests. In any case, the incident reminded the public that opposition to the war might not only end your career but your liberty as well.

A lively question and answer session followed the reading, moderated by the prominent journalist Angelina Davydova and featuring the German novelist Elke Schmitter. Many of the Germans in attendance wondered what lay behind the charges and the arrests, giving the performers an opportunity to explain how the Russian state manipulates the law and courts to punish its opponents.

The event proved a powerful example of how Russian theater in emigration can be a vehicle to educate Westerners about the nuances of Putin’s authoritarianism and Russian society as a whole. “It was essential for us to not make this something for ourselves [Russians] and to draw visibility to the [arrests] to a wider audience,” Sapizhak told me of the reading during a telephone interview later.

Unlike Lenik and many other Russian actors who had returned and were once accustomed to performing on bigger stages, Sapizhak—who produced underground shows for “little pay” in Russia and lacks a formal theater education—has not found it as psychologically difficult to adapt to her new surroundings. Many of the shows she produced in Russia were already illuminating issues plaguing society, such as domestic abuse and police brutality.

She moved to Berlin last summer after obtaining an Artists at Risk visa and plans to continue living and working in Germany, now on a freelance visa. Concurrently with her work on Finist the Brave Falcon, Sapizhak was collecting testimonies from Russians who remained in the country but opposed its politics. The testimonies were read aloud in a show called innervoice.ru, which she directed and starred in.

“I did everything I f**king could,” one testimony reads. “I went to these f**king rallies, posted these f**king stories to Instagram [about Russian war crimes] in the hope that my relatives would wake up, donated to these humanitarian aid groups. That’s it, my duties have ended.”

“I’m on antidepressants,” reads another. “Without them, it’s not even that I wouldn’t be able to leave Russia—I wouldn’t even be able to leave my apartment.”

For the German audiences who saw her show, Sapizhak said, hearing the testimonies was a revelatory experience that provided nuance and insight into the psychology of those who remain in the country.

As for her fellow actors who returned or remain, Sapizhak does not pass judgement. “I understand that these decisions to return, to stay or even to leave are all very difficult,” she said. “There is no right answer.”

But when analyzing her own choice to pursue a life abroad, she said that if she were to ever have children in the future, she would at least have an answer if they were to ask what she did at this moment.

After the Finist the Brave Falcon reading concluded, donations were collected for the two imprisoned artists. While conversations and events in support of Berkovich and Petriichuk are possible in emigration, the subject of their fate is taboo among actors and directors still in Russia, the independent Russian media outlet Vyorstka stated, adding that Their former colleagues refuse to publicly comment on the “cultural catastrophe” that is their arrest.

An uncertain future

Lenik realized he wanted to become an actor after seeing the American star Jim Carrey perform on Larry Sanders’s farewell show. Grabbing a microphone, Carrey danced through the audience in his characteristically spasmodic manner, singing a tribute to the iconic talkshow host. “I was so moved by Carrey’s performance that I realized I wanted to do the same,” Lenik said.

He can mimic the many facial expressions of his gesticulating idol Carrey on command, and he belts out the closest approximation of Tom Waits’s idiosyncratic baritone I have ever heard. His role models are both Soviet poets and actors and products of the American entertainment industry, which he lives and breathes.

When he was an exchange student in Los Angeles, one of his teachers, who he claims was an ex-girlfriend of the actor Eddie Murphy, urged him to apply to the Lee Strasberg Theater and Film Institute, the prestigious acting school with campuses in New York City and Los Angeles. He was accepted but declined the offer after he fell in love with a girl back in Russia, to which he returned to study at the Moscow Art Theater. Had he gone to the Strasberg school, he would probably now be singing a different tune, perhaps on Broadway.

In the few conversations we have had since his return to Moscow, Lenik was emotional. He detested what had become of Moscow’s theater culture—the thing he most cherishes. But he refused to elaborate on those grievances on the record because of a combination of safety concerns, a desire “not to throw others under the bus” and a claimed revulsion for sensationalism and “media.” From past conversations, I know the arrests of Berkovich and Petriichuk weigh heavily on his mind.

His withdrawn communication with me felt symptomatic of the behavior some sociologists have ascribed to those remaining in Putin’s Russia. Surrounded by an ever-repressive environment where speaking out can land them in jail, and facing the logistically and ethically difficult choice of whether to emigrate, many feel impotent and keep their heads down.

“Our process of dividing things into black and white is much bigger in our minds than in reality,” Titov said of his fellow actors back in Russia. “It’s a natural reaction [to return].”

But for many, the decision has also brought a constant state of questioning and unease about their present and future in a society in which, like in the Leonid Brezhnev-era Soviet Union, artists are forced to make difficult compromises just to put food on the table.

Top photo: Russian émigré actors in Berlin stage a play about the exiled Soviet writer Aleksandr Galich